China and Yemen's Forgotten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gawc Link Classification FINAL.Xlsx

High Barcelona Beijing Sufficiency Abu Dhabi Singapore sufficiency Boston Sao Paulo Barcelona Moscow Istanbul Toronto Barcelona Tokyo Kuala Lumpur Los Angeles Beijing Taiyuan Lisbon Madrid Buenos Aires Taipei Melbourne Sao Paulo Cairo Paris Moscow San Francisco Calgary Hong Kong Nairobi New York Doha Sydney Santiago Tokyo Dublin Zurich Tokyo Vienna Frankfurt Lisbon Amsterdam Jakarta Guangzhou Milan Dallas Los Angeles Hanoi Singapore Denver New York Houston Moscow Dubai Prague Manila Moscow Hong Kong Vancouver Manila Mumbai Lisbon Milan Bangalore Tokyo Manila Tokyo Bangkok Istanbul Melbourne Mexico City Barcelona Buenos Aires Delhi Toronto Boston Mexico City Riyadh Tokyo Boston Munich Stockholm Tokyo Buenos Aires Lisbon Beijing Nanjing Frankfurt Guangzhou Beijing Santiago Kuala Lumpur Vienna Buenos Aires Toronto Lisbon Warsaw Dubai Houston London Port Louis Dubai Lisbon Madrid Prague Hong Kong Perth Manila Toronto Madrid Taipei Montreal Sao Paulo Montreal Tokyo Montreal Zurich Moscow Delhi New York Tunis Bangkok Frankfurt Rome Sao Paulo Bangkok Mumbai Santiago Zurich Barcelona Dubai Bangkok Delhi Beijing Qingdao Bangkok Warsaw Brussels Washington (DC) Cairo Sydney Dubai Guangzhou Chicago Prague Dubai Hamburg Dallas Dubai Dubai Montreal Frankfurt Rome Dublin Milan Istanbul Melbourne Johannesburg Mexico City Kuala Lumpur San Francisco Johannesburg Sao Paulo Luxembourg Madrid Karachi New York Mexico City Prague Kuwait City London Bangkok Guangzhou London Seattle Beijing Lima Luxembourg Shanghai Beijing Vancouver Madrid Melbourne Buenos Aires -

Prometric Combined Site List

Prometric Combined Site List Site Name City State ZipCode Country BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA LAB.1 Buenos Aires ARGENTINA 1006 ARGENTINA YEREVAN, ARMENIA YEREVAN ARMENIA 0019 ARMENIA Parkus Technologies PTY LTD Parramatta New South Wales 2150 Australia SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA Sydney NEW SOUTH WALES 2000 NSW AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Melbourne VICTORIA 3000 VIC AUSTRALIA PERTH, AUSTRALIA PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 6155 WA AUSTRALIA VIENNA, AUSTRIA Vienna AUSTRIA A-1180 AUSTRIA MANAMA, BAHRAIN Manama BAHRAIN 319 BAHRAIN DHAKA, BANGLADESH #8815 DHAKA BANGLADESH 1213 BANGLADESH BRUSSELS, BELGIUM BRUSSELS BELGIUM 1210 BELGIUM Bermuda College Paget Bermuda PG04 Bermuda La Paz - Universidad Real La Paz BOLIVIA BOLIVIA GABORONE, BOTSWANA GABORONE BOTSWANA 0000 BOTSWANA Physique Tranformations Gaborone Southeast 0 Botswana BRASILIA, BRAZIL Brasilia DISTRITO FEDERAL 70673-150 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 31140-540 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 30160-011 BRAZIL CURITIBA, BRAZIL Curitiba PARANA 80060-205 BRAZIL RECIFE, BRAZIL Recife PERNAMBUCO 52020-220 BRAZIL RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL Rio de Janeiro RIO DE JANEIRO 22050-001 BRAZIL SAO PAULO, BRAZIL Sao Paulo SAO PAULO 05690-000 BRAZIL SOFIA LAB 1, BULGARIA SOFIA BULGARIA 1000 SOFIA BULGARIA Bow Valley College Calgary ALBERTA T2G 0G5 Canada Calgary - MacLeod Trail S Calgary ALBERTA T2H0M2 CANADA SAIT Testing Centre Calgary ALBERTA T2M 0L4 Canada Edmonton AB Edmonton ALBERTA T5T 2E3 CANADA NorQuest College Edmonton ALBERTA T5J 1L6 Canada Vancouver Island University Nanaimo BRITISH COLUMBIA V9R 5S5 Canada Vancouver - Melville St. Vancouver BRITISH COLUMBIA V6E 3W1 CANADA Winnipeg - Henderson Highway Winnipeg MANITOBA R2G 3Z7 CANADA Academy of Learning - Winnipeg North Winnipeg MB R2W 5J5 Canada Memorial University of Newfoundland St. -

A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The

BECOMING ONE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NATIONAL UNIFICATION IN VIETNAM, YEMEN AND GERMANY A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Conflict Resolution By Min Jung Kim, B.A. Washington, DC May 1, 2009 I owe my most sincere gratitude to my thesis advisor Kevin Doak, Ph.D. for his guidance and support and to Aviel Roshwald, Ph.D. and Tristan Mabry, Ph.D. for detailed and constructive comments. Min Jung Kim ii BECOMING ONE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NATIONAL UNIFICATION IN VIETNAM, YEMEN AND GERMANY Min Jung Kim, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Kevin M. Doak, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to understand the dynamic processes of modern national unification cases in Vietnam (1976), Yemen (1990) and Germany (1990) in a qualitative manner within the framework of Amitai Etizoni’s political integration theory. There has been little use of this theory in cases of inter-state unification despite its apparent applicability. This study assesses different factors (military force, utilitarian and identitive factors) that influence unification in order to understand which were most supportive of unification and which resulted in a consolidation unification in the early to intermediate stages. In order to answer the above questions, the thesis uses the level of integration as a dependent variable and the various methods of unification as independent variables. The dependent variables are measured as follows: whether unified states were able to protect its territory from potential violence and secessions and to what extent alienation emerged amongst its members. -

FROM the G7 to a D-10: Strengthening Democratic Cooperation for Today’S Challenges

FROM THE G7 TO THE D-10 : STRENGTHENING DEMOCRATIC COOPERATION FOR TODAY’S CHALLENGES FROM THE G7 TO A D-10: Strengthening Democratic Cooperation for Today’s Challenges Ash Jain and Matthew Kroenig (United States) With Tobias Bunde (Germany), Sophia Gaston (United Kingdom), and Yuichi Hosoya (Japan) ATLANTIC COUNCIL A Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. Democratic Order Initiative This report is a product of the Scowcroft Center’s Democratic Order Initiative, which is aimed at reenergizing American global leadership and strengthening cooperation among the world’s democracies in support of a rules-based democratic order. The authors would like to acknowledge Joel Kesselbrenner, Jeffrey Cimmino, Audrey Oien, and Paul Cormarie for their efforts and contributions to this report. This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. © 2021 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. -

The Two Yemens

1390_A24-A34 11/4/08 5:14 PM Page 543 330-383/B428-S/40005 The Two Yemens 171. Telegram From the Department of State to the Embassy in the People’s Republic of Southern Yemen1 Washington, February 27, 1969, 1710Z. 30762. Subj: US–PRSY Relations. 1. PRSY UN Perm Rep Nu’man,2 who currently in Washington as PRSYG observer at INTELSAT Conference, had frank but cordial talk with ARP Country Director Brewer February 26. 2. In analyzing causes existing coolness in USG–PRSYG relations, Ambassador Nu’man claimed USG failure offer substantial aid at time of independence and subsequent seizure of American arms with clasped hands insignia3 in possession of anti-PRSYG dissidents had led Aden to “natural” conclusion that USG distrusts PRSYG. He specu- lated this due to close US relationship with Saudis whom Nu’man al- leged, somewhat vaguely, had privately conveyed threats to overthrow NLF regime, claiming USG support. Nu’man asserted PRSYG desired good relations with USG and hoped USG would reciprocate. 3. Recalling history of USG attempts to develop good relations with PRSYG, Brewer underlined our feeling it was PRSYG which had not re- ciprocated. He reviewed our position re non-interference PRSY internal affairs, regretting publicity anti-USG charges (e.g. re arms) without first seeking our explanation. Brewer noted USG seeks maintain friendly relations with Saudi Arabia as well as PRSYG but we not responsible for foreign policy of either. 4. Nu’man reiterated SAG responsible poor state Saudi-PRSY con- tacts. Brewer demurred, noting SAG had good reasons be concerned over hostile attitude PRSYG leaders. -

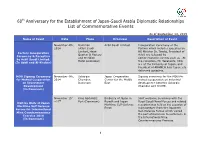

List of the Commemorative Events(PDF)

60th Anniversary for the Establishment of Japan-Saudi Arabia Diplomatic Relationships List of Commemorative Events As of September 14, 2015 Name of Event Date Place Organizer Description of Event November 4th, Damman Azbil Saudi Limited. Inauguration Ceremony of the 2014 (Azbil Saudi Factory which includes speeches by Limited, Head HE Minister Dr. Tawfig, President of Factory Inauguration Quarter & Factory Azbil, etc followed by Ceremony & Reception and Meridien commemorative events such as . At by Azbil Saudi Limited. Hotel Al-Khobar) the reception, Mr. Takahashi, CDA (In Azbil and Al-Khobar) a.i. at the Embassy of Japan, and President of ARAMCO Asia Japan, etc delivered speeches. MOU Signing Ceremony November 4th, Asharqia Japan Cooperation Signing ceremony for the MOU for for Mutual Cooperation 2014 Chamber, Center for the Middle mutual cooperation on industrial on Investment Dammam East development between Asharqia Development Chamber and JCCME. (In Dammam) November 15th King Abdulaziz Embassy of Japan in Joint welcome ceremony with the ~17th Port (Dammam) Riyadh and Japan Royal Saudi Naval Forces and related Visit by Units of Japan Maritime Self-Defense reception was held on the occasion of Maritime Self Defense Force minesweeper from the Japanese Forces for International Self-Defense Forces which visited Mine Countermeasures the port of Dammam to participate in Exercise 2014 the International Mine (In Dammam) Countermeasures Exercise. 1 Name of Event Date Place Organizer Description of Event November 18th King Fahd Cultural Embassy of Japan in The Embassy participated in the 7th ~22nd Center (Riyadh) Riyadh, Ministry of International Children’s Day Festival Culture and and showed a Japanese calligraphy, Participation to the 7th Information Origami, and Japanese traditional International Children’s garments. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 226/Monday, November 23, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 226 / Monday, November 23, 2020 / Notices 74763 antitrust plaintiffs to actual damages Fairfax, VA; Elastic Path Software Inc, DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE under specified circumstances. Vancouver, CANADA; Embrix Inc., Specifically, the following entities Irving, TX; Fujian Newland Software Antitrust Division have become members of the Forum: Engineering Co., Ltd, Fuzhou, CHINA; Notice Pursuant to the National Communications Business Automation Ideas That Work, LLC, Shiloh, IL; IP Cooperative Research and Production Network, South Beach Tower, Total Software S.A, Cali, COLOMBIA; Act of 1993—Pxi Systems Alliance, Inc. SINGAPORE; Boom Broadband Limited, KayCon IT-Consulting, Koln, Liverpool, UNITED KINGDOM; GERMANY; K C Armour & Co, Croydon, Notice is hereby given that, on Evolving Systems, Englewood, CO; AUSTRALIA; Macellan, Montreal, November 2, 2020, pursuant to Section Statflo Inc., Toronto, CANADA; Celona CANADA; Mariner Partners, Saint John, 6(a) of the National Cooperative Technologies, Cupertino, CA; TelcoDR, CANADA; Millicom International Research and Production Act of 1993, Austin, TX; Sybica, Burlington, Cellular S.A., Luxembourg, 15 U.S.C. 4301 et seq. (‘‘the Act’’), PXI CANADA; EDX, Eugene, OR; Mavenir Systems Alliance, Inc. (‘‘PXI Systems’’) Systems, Richardson, TX; C3.ai, LUXEMBOURG; MIND C.T.I. LTD, Yoqneam Ilit, ISRAEL; Minima Global, has filed written notifications Redwood City, CA; Aria Systems Inc., simultaneously with the Attorney San Francisco, CA; Telsy Spa, Torino, London, UNITED KINGDOM; -

GCC Policies Toward the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen: Ally-Adversary Dilemmas by Fred H

II. Analysis Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Abu Dhabi, and King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, Saudi Arabia, preside over the ‘Sheikh Zayed Heritage Festival 2016’ in Abu Dhabi, UAE, on 4 December 2016. GCC Policies Toward the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen: Ally-Adversary Dilemmas by Fred H. Lawson tudies of the foreign policies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries usually ignore import- S ant initiatives that have been undertaken with regard to the Bab al-Mandab region, an area encom- passing the southern end of the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have become actively involved in this pivotal geopolitical space over the past decade, and their relations with one another exhibit a marked shift from mutual complementarity to recip- rocal friction. Escalating rivalry and mistrust among these three governments can usefully be explained by what Glenn Snyder calls “the alliance security dilemma.”1 Shift to sustained intervention Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE have been drawn into Bab al-Mandab by three overlapping develop- ments. First, the rise in world food prices that began in the 2000s incentivized GCC states to ramp up investment in agricultural land—Riyadh, Doha and Abu Dhabi all turned to Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda as prospective breadbaskets.2 Doha pushed matters furthest by proposing to construct a massive canal in central Sudan that would have siphoned off more than one percent of the Nile River’s total annual downstream flow to create additional farmland. -

Could a Reunification Spark Growth for the Korean Economy? Stephen P

Citations Journal of Undergraduate Research Wagner, S. The North Is Coming: Could A Reunification Spark Growth for The Korean Economy? Stephen P. Wagner Faculty Sponsor: Dr. John A. Tures Program: Political Science North Korea’s Kim Jong-un has recently made an effort to shake hands with President Donald J. Trump and South Korea’s President, Moon Jae-in. For its two biggest rivals, this was the first-ever meeting between leaders of United States and North Korea; also, South and North Korea met for the first time since the Korean War ended in 1953. This paper will examine whether North Korea could unify peacefully or conflict with its neighbor South Korea. In more detail, it will measure different cases of countries that have unified peacefully or with war. The paper will determine whether (GDP) growth is positively identified before and after unification between both peaceful and conflict cases. Literature Review Rug.nl, The Groningen Growth and Development Centre (GGDC), presents us with the data for my cases that we are examining. The Groningen Growth and Development Centre writes,” The GGDC provides unique information on comparative trends in the world economy in the form of easily accessible datasets, along with comprehensive documentation. These data are made publicly available, which enables researchers and policy makers from all over the world to analyze productivity, structural change, and economic growth in detail” (2017, Par. 2). The database in th e (GGDC), Penn World Tables, gives me every year dating from almost a century ago. This is instrumental for me to determine the correlations that can be involved when I look at the times my cases unified. -

The Republic of Korea and the Middle East

AugustApril 2010 • Volume 5 • Number 64 TheCosponsorship Republic of Korea of North and Koreathe Middle Bills East:in the U.S.Economics, House of Diplomacy, Representatives, and Security 1993–2009 by Alonby Jungkun Levkowitz Seo South(Mr. Korean–Middle GILMAN) Mr. Eastern Speaker, relations I rise tohave voice been my ne - Historicalto fi ll this gap, Connections: this article explores 1950s–1960s congressional politics to- glectedstrong in thesupport literature for throughoutH. Con. Res. the years, 213, mainlyregarding owing ward North Korea policy in the post–Cold War period. to theNorth focus Korean on Korea’s refugees relations who withare detained the United in States China and Until the 1960s, Seoul’s policy toward the Middle East Asianand states forcibly and returned the attention to North given Korea to the whereNorth Korea–they couldThe case be ofdefined the Democratic as passive, People’s if not unimportant, Republic of Koreaowing (DPRK) to Middleface Easttorture, military imprisonment, trade. This and paper execution. sheds new I thank light on Korea’sprovides lack an excellent of interests test in of the diverse Middle hypotheses East. During of cosponsor- the thisthe issue gentleman by analyzing from South California Korea’s (Mr. Middle ROYCE) East policy.for firstship activitiesyears after byits Houseestablishment members. in 1948, Preventing South Koreanuclear was prolif- Untilbringing the 1960s, this importantthe Middle resolution East was beforeof low us importance today. preoccupiederation and promoting with nation human building. rights The haveKorean become War, which key foreign to South(Congressional Korea because Record, of Korea’s H3418, lack June of economic 11, 2002) and eruptedpolicy agendas two years for later,the United left South States Korea since with the endone ofmain the Cold political interest in the region. -

The IMF and the World Bank in an Evolving World

3 The IMF and the World Bank in an Evolving World This session fea tured two speakers from major countries who have played ac tive and important roles in their countries for many years. The first speaker was Manmohan Singh, the Finance Minister of India and one of the chief archi tects of lndia's recent economic reform program. He was followed by C. Fred Bergsten, the founder and Director of the Institute for International Economics and a fo nner Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Tr easury Department. After they addressed the global issues affecting the Bretton Woods institutions from their unique perspectives, the Chairman of the session-lıımberto Dini, Minister of the Tr easury of Italy-offered an overview and synthesis of the suggestions presented. The speakers then responded to a number of questions and com ments raised by other participants. Manmohan Singh When I was invited to speak at this conference, I accepted with great pleasure. Fiftieth anniversaries are festive occasions when old friends gather to relive pleasant memories, to rejoice and felicitate. I have been privileged, in various capacities in the Government of India, to dea! with the Bretton Woods institutions for almost half of the 50 years we are commemorating today. I have innumerable pleasant memories and old friends associated with these institutions and it is therefore a partic ular pleasure to be part of this celebration. Twoscore and ten years is not a very long time for historians, but it is time enough to reflect on the achievements of institutions and draw new blueprints for the future. -

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background the Yemen Civil War Is

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background The Yemen civil war is currently in its fifth year, but tensions within the country have existed for many years. The conflict in Yemen has been labelled as the worst humanitarian crisis in the world by the United Nations (UN) and is categorized as a man-made phenomenon. According to the UN, 80% of the population of Yemen need humanitarian assistance, with 2/3 of its population considered to be food insecure while 1/3 of its population is suffering from extreme levels of hunger and most districts in Yemen at risk of famine. As the conditions in Yemen continue to deteriorate, the world’s largest cholera outbreak occurred in Yemen in 2017 with a reported one million infected.1 Prior to the conflict itself, Yemen has been among the poorest countries in the Arab Peninsula. However, that is contradictory considering the natural resources that Yemen possess, such as minerals and oil, and its strategical location of being adjacent to the Red Sea.2 Yemen has a large natural reserve of natural gasses and minerals, with over 490 billion cubic meters as of 2010. These minerals include the likes of silver, gold, zinc, cobalt and nickel. The conflict in Yemen is a result of a civil war between the Houthi, with the help of Former President Saleh, and the Yemen government that is represented by 1 UNOCHA. “Yemen.” Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019, 2019. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2019_Yemen_HNO_FINAL.pdf. 2 Sophy Owuor, “What Are The Major Natural Resources Of Yemen?” WorldAtlas, February 19, 2019.