The Herbert Baum Group Blog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Origin Story

L’CHAYIM www.JewishFederationLCC.org Vol. 41, No. 11 n July 2019 / 5779 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Our origin story 6 Our Community By Brian Simon, Federation President 7 Jewish Interest very superhero has an origin to start a High School in Israel pro- people 25 years old or younger to trav- story. Spiderman got bit by a gram, and they felt they needed a local el to Israel to participate in volunteer 8 Marketplace Eradioactive spider. Superman’s Federation to do that. So they started or educational programs. The Federa- father sent him to Earth from the planet one. The program sent both Jews and tion allocates 20% of its annual budget 11 Israel & the Jewish World Krypton. Barbra non-Jews to study in Israel. through the Jewish Agency for Israel 14 Commentary Streisand won a Once the Federation began, it (JAFI), the Joint Distribution Commit- 16 From the Bimah talent contest at a quickly grew and took on new dimen- tee (JDC) and the Ethiopian National gay nightclub in sions – dinner programs, a day camp, Project (ENP) to social service needs 18 Community Directory Greenwich Vil- a film festival and Jewish Family Ser- in Israel, as well as to support Part- 19 Focus on Youth lage. vices. We have sponsored scholarships nership Together (P2G) – our “living Our Jewish and SAT prep classes for high school bridge” relationship with the Hadera- 20 Organizations Federation has its students (both Jews and non-Jews). We Eiron Region in Israel. 22 Temple News own origin story. stopped short of building a traditional In the comics, origin stories help n Brian There had already Jewish Community Center. -

Marianne Cohn Et Son Action De Résistance

Ruth Fivaz-Silbermann Historienne, Genève Marianne Cohn et son action résistante L'action L'action de Marianne Cohn à la frontière franco-suisse s'inscrit dans le travail de la Résistance juive au plan d'extermination des nazis. Marianne fait partie d'un réseau créé au printemps 1942, appelé «Mouvement de la Jeunesse sioniste». Ce réseau procure des caches et des faux papiers aux juifs étrangers ou français, menacés sur tout le territoire d'arrestation et de déportation, parce qu'ils sont juifs. Il travaille en étroite collaboration avec le réseau des Eclaireurs israélites de France. Leur objectif principal est de sauver des enfants et des adolescents juifs, notamment en les faisant passer en Suisse. La Suisse a autorisé, fin 1943, l'arrivée de 1'500 enfants juifs de France. Après avoir travaillé à Moissac, à Nice et à Grenoble, Marianne, qui a 21 ans, est chargée début 1944 par son réseau de convoyer des groupes d'enfants et de jeunes vers la Suisse, à la frontière genevoise. Elle travaille sous les ordres de Simon Lévitte, chef du mouvement, et d'Emmanuel «Mola» Racine, chef du service de passage en Suisse et frère de Mila Racine, qui a été arrêtée sur cette même frontière le 21 octobre précédent. L’équipe compte cinq ou six résistants, dont Hélène Bloch, Rolande Birgy et Colette Dufournet. Mais Marianne sera la plus active: elle convoie neuf groupes d'enfants en avril et mai 1944, soit 207 enfants au total. Hélas, elle est arrêtée le 31 mai 1944, avec les 32 enfants de son dernier convoi. -

Widerstand in Berlin Gegen Das NS-Regime 1933 Bis 1945

Widerstand in Berlin gegen das NS-Regime 1933 bis 1945 - Ein biographisches Lexikon - 1. Auflage Das Gesamtlexikon (12 Bände) hat die ISBN 3-89626-350-1 trafo verlag 2002-2005 Nachfolgend Auszüge aus dem Band 10 des Lexikons ISBN 978-3-89626-360-5 Verzeichnisse Infos zum Buch: http://www.trafoberlin.de/3-89626-360-9.html Widerstand in Berlin gegen das NS-Regime 1933 bis 1945 Ein biographisches Lexikon Band 10 Verzeichnisse Autor Hans-Joachim Fieber unter Mitarbeit von Günter Wehner trafo verlag Bibliografische Informationen Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar Herausgegeben von der Geschichtswerkstatt der Berliner Vereinigung ehemaliger Teilnehmer am antifaschistischen Widerstand, Verfolgter des Naziregimes und Hinterbliebener (BV VdN) e.V. unter Leitung von Hans-Joachim Fieber Herausgeberkollegium des Lexikons: Lothar Berthold, Hans-Joachim Fieber, Klaus Keim, Günter Wehner Autoren des Lexikons: Michele Barricelli, Lothar Berthold, Hans-Joachim Fieber, Klaus Keim, René Mounajed, Oliver Reschke und Günter Wehner Impressum Widerstand in Berlin gegen das NS-Regime 1933–1945. Ein biographisches Lexikon. Hrsg. von der Geschichtswerkstatt der Berliner Vereinigung ehemaliger Teilnehmer am antifaschistischen Widerstand, Verfolgter des Naziregimes und Hinterbliebener (BV VdN) e.V. unter Leitung von Hans-Joachim Fieber. trafo verlag 2002–2005 Gesamtlexikon: ISBN 3-89626-350-1 Band 10: Verzeichnisse Autor: Hans-Joachim Fieber unter Mitarbeit von Günter Wehner ISBN 3-89626-360-9 1. Auflage 2005 © trafo verlag dr. wolfgang weist Finkenstraße 8, 12621 Berlin Umschlaggestaltung: trafo verlag Umschlagfotos: s. Bildnachweis Druck u. Verarbeitung: SDL oHG, Berlin Printed in Germany 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort ............................................................................................................................ -

CASE STUDY the Rise of Nazism and the Destruction of European Jewry

CASE STUDY The Rise of Nazism and the Destruction of European Jewry 148 Darlinghurst Road, Darlinghurst NSW 2010 T 02 9360 7999 F 02 9331 4245 E [email protected] sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au Acknowledgements Karen Finch, Education Officer Avril Alba, Director of Education Sophie Gelski, extract from Teaching the Holocaust Susi Brieger, Education Consultant The contributors also wish to thank Dr Konrad Kwiet, Resident Historian, Sydney Jewish Museum. Every effort has been made to contact or trace all copyright holders. The publishers will be grateful to be notified of any additions, errors or omissions that should be incorporated in the next edition. These materials were prepared by the Education Department of the Sydney Jewish Museum for use in the program, The Rise of Nazism and the Destruction of European Jewry. They may not be reproduced for other purposes without the express permission of the Sydney Jewish Museum. Copyright, Sydney Jewish Museum 2008. All rights reserved. Design by ignition point Dear Teacher Please find enclosed pre visit materials, lesson plan and post visit materials for you to use in the classroom to support student learning at the Sydney Jewish Museum (SJM). The Rise of Nazism and the Destruction of European Jewry program will introduce concepts from Option C: Germany 1919-1939, Part II: National Studies. The content and learning experiences are linked to syllabus outcomes. Students will investigate ■ the nature and influence of racism ■ changes in society ■ the nature and impact of Nazism Students will learn about ■ Nazi racial policy; antisemitism; policy and practice to 1939 At the Museum, your students will meet a Holocaust survivor or descendant and hear first hand experiences of the period. -

The Hunt for the Holy Wheat Grail: a Not So 'Botanical' Expedition in 1935

The Hunt for the Holy Wheat Grail: A not so ‘botanical’ expedition in 1935 Author : Thomas Ruttig Published: 20 July 2015 Downloaded: 6 September 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/the-hunt-for-the-holy-wheat-grail-a-not-so-botanical-expedition- in-1935/?format=pdf AAN has just reported about an area in Central Afghanistan, the Shah Foladi in the Koh-e Baba mountain range, that was recently declared a new conservation area for its botanical diversity. This reminded AAN’s co-director Thomas Ruttig of a first ‘botanical’ expedition – 80 years ago, in 1935 – to another isolated mountainous region of Afghanistan: Nuristan. It was organised by Germany, and it was the first scientific expedition allowed into the country by the Afghan government after the reign of Amanullah (apart from the Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA) that came in 1922 by request of the Afghan government). But the German Nazi regime was not only after plants. On the morning of 28 May [1935], we depart from Kabul. A last piece of luggage is handed onto the lorry, a last rope tied. Undecided we stand in the garden of the German legation. Maybe, 1 / 8 we shall return in two weeks as the defeated heroes. ‘Inshallah’, God willing, we shall succeed. The route leads parallel to the northern slopes of the Safid Koh. It is a powerful landscape of gravel, folded and jagged, traces of ice age flows. Over depressions and heights, the road leads, soon down into the bed of a dried out river, then up again into altitudes of more than 3000 meters. -

Religious and Secular Responses to Nazism: Coordinated and Singular Acts of Opposition

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition Kathryn Sullivan University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Sullivan, Kathryn, "Religious And Secular Responses To Nazism: Coordinated And Singular Acts Of Opposition" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 891. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/891 RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR RESPONSES TO NAZISM COORDINATED AND SINGULAR ACTS OF OPPOSITION by KATHRYN M. SULLIVAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2003 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2006 © 2006 Kathryn M. Sullivan ii ABSTRACT My intention in conducting this research is to satisfy the requirements of earning a Master of Art degree in the Department of History at the University of Central Florida. My research aim has been to examine literature written from the 1930’s through 2006 which chronicles the lives of Jewish and Gentile German men, women, and children living under Nazism during the years 1933-1945. -

Lettre R”Sistance N¡38

LA LETTRE de la Fondation de la Résistance Reconnue d’utilité publique par décret du 5 mars 1993. Sous le Haut Patronage du Président de la République N° 38 - septembre 2004 - 4,50 € Le débarquement de Provence et la Résistance Commission archives SAUVEGARDER LES ARCHIVES PRIVÉES DE LA RÉSISTANCE ET DE LA DÉPORTATION : UNE EXPOSITION VOUS Y AIDE. Sauvegarder les archives de la Résistance et de la Déportation est l'une des conditions pour permettre d’écrire l’histoire de cette période et pour préserver la mémoire. À cet effet, en partenariat avec le Crédit municipal de Paris, les Fondations de la Résistance et pour la Mémoire de la Déportation, associées aux ministères de la Défense et de la Culture, viennent de réaliser une exposition qui aidera tous les détenteurs d’archives, à les préserver et à les transmettre. L’objectif de l’exposition « Ensemble, sauvegardons et les archives des associations, en insistant sur le fait les archives privées de la Résistance et de la Dépor- que tous ces documents sont intéressants pour les his- tation » est de sensibiliser tous les particuliers possé- toriens futurs ; dant des documents relatifs à l'histoire de la Résistance - « La sauvegarde des archives est un devoir » insiste et de la Déportation, quelle que soit leur origine et sur les avantages qu’il y a pour un particulier à céder leur forme - écrits personnels, archives des organisa- ses papiers à un centre public d’archives qui seul offre tions de Résistance et des associations dédiées à la le maximum de garanties tant du point de vue de la mémoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, des- conservation des documents que de leur communi- sins, textes, tracts, faux papiers.. -

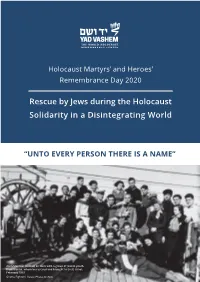

Rescue by Jews During the Holocaust Solidarity in a Disintegrating World

Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day 2020 Rescue by Jews during the Holocaust Solidarity in a Disintegrating World “UNTO EVERY PERSON THERE IS A NAME” Aron Menczer (center) on deck with a group of Jewish youth from Vienna, whom he rescued and brought to Eretz Israel, February 1939 Ghetto Fighters’ House Photo Archive Jerusalem, Nissan 5780 April 2020 “Unto Every Person There Is A Name” Public Recitation of Names of Holocaust Victims in Israel and Abroad on Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day “Unto every person there is a name, given to him by God and by his parents”, wrote the Israeli poetess Zelda. Every single victim of the Holocaust had a name. The vast number of Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust – some six million men, women and children - is beyond human comprehension. We are therefore liable to lose sight of the fact that each life that was brutally ended belonged to an individual, a human being endowed with feelings, thoughts, ideas and dreams whose entire world was destroyed, and whose future was erased. The annual recitation of names of victims on Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day is one way of posthumously restoring the victims’ names, of commemorating them as individuals. We seek in this manner to honor the memory of the victims, to grapple with the enormity of the murder, and to combat Holocaust denial and distortion. This year marks the 31st anniversary of the global Shoah memorial initiative “Unto Every Person There Is A Name”, held annually under the auspices of the President of the State of Israel. -

German Jews in the Resistance 1933 – 1945 the Facts and the Problems © Beim Autor Und Bei Der Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand

Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand German Resistance Memorial Center German Resistance 1933 – 1945 Arnold Paucker German Jews in the Resistance 1933 – 1945 The Facts and the Problems © beim Autor und bei der Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand Redaktion Dr. Johannes Tuchel Taina Sivonen Mitarbeit Ute Stiepani Translated from the German by Deborah Cohen, with the exception of the words to the songs: ‘Song of the International Brigades’ and ‘The Thaelmann Column’, which appear in their official English-language versions, and the excerpt from Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s poem ‘Beherzigung’, which was translated into English by Arnold Paucker. Grundlayout Atelier Prof. Hans Peter Hoch Baltmannsweiler Layout Karl-Heinz Lehmann Birkenwerder Herstellung allprintmedia GmbH Berlin Titelbild Gruppe Walter Sacks im „Ring“, dreißiger Jahre. V. l. n. r.: Herbert Budzislawski, Jacques Littmann, Regine Gänzel, Horst Heidemann, Gerd Meyer. Privatbesitz. This English text is based on the enlarged and amended German edition of 2003 which was published under the same title. Alle Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Germany 2005 ISSN 0935 - 9702 ISBN 3-926082-20-8 Arnold Paucker German Jews in the Resistance 1933 – 1945 The Facts and the Problems Introduction The present narrative first appeared fifteen years ago, in a much-abbreviated form and under a slightly different title.1 It was based on a lecture I had given in 1988, on the occasion of the opening of a section devoted to ‘Jews in the Resistance’ at the Berlin Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand, an event that coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the Kristallnacht pogrom. As the Leo Baeck Institute in London had for many years been occupied with the problem, representation and analysis of Jewish self-defence and Jewish resistance, I had been invited to speak at this ceremony. -

Russia and the Russians in the Eyes of the Spanish

Article Journal of Contemporary History 2017, Vol. 52(2) 352–374 Russia and the Russians ! The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav in the Eyes of the DOI: 10.1177/0022009416647118 Spanish Blue Division journals.sagepub.com/home/jch soldiers, 1941–4 Xose´ M. Nu´n˜ez Seixas Ludwig-Maximilians-Universita¨t, Munich, Germany Abstract The Spanish ‘Blue Division’ has received significant historiographical and literary atten- tion. Most research has focused on diplomacy and the role of the Division in fostering diplomatic relations between Spain and Germany during the Second World War. However, the everyday experience of Spanish soldiers on the Eastern Front, the occu- pation policy of the Blue Division and its role in the Nazi war of extermination remain largely unexplored. It is commonly held that the Spanish soldiers displayed more benign behaviour towards the civilian population than did the Germans. Although this tendency can generally be confirmed, Spanish soldiers were known for stealing, requisitioning and occasional acts of isolated violence; and also for the almost complete absence of col- lective, organized retaliation. Yet how did Spanish soldiers perceive the enemy, particu- larly Soviet civilians? To what degree did the better behaviour of Spanish occupying forces towards the civilian population reflect a different view of the enemy, which differed from that of most German soldiers? Keywords Blue Division, Eastern Front, Fascism, image of the enemy, Second World War, war violence The Divisio´n Espan˜ola de Voluntarios, or Spanish Division of Volunteers, was set up by the Franco Regime in early summer 1941, to take part in the Russian cam- paign as a unit integrated in the German Wehrmacht. -

Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1933-1945

NAZI GERMANY AND THE JEWS, 1933–1945 ABRIDGED EDITION SAUL FRIEDLÄNDER Abridged by Orna Kenan To Una CONTENTS Foreword v Acknowledgments xiii Maps xv PART ONE : PERSECUTION (January 1933–August 1939) 1. Into the Third Reich: January 1933– December 1933 3 2. The Spirit of the Laws: January 1934– February 1936 32 3. Ideology and Card Index: March 1936– March 1938 61 4. Radicalization: March 1938–November 1938 87 5. A Broken Remnant: November 1938– September 1939 111 PART TWO : TERROR (September 1939–December 1941) 6. Poland Under German Rule: September 1939– April 1940 143 7. A New European Order: May 1940– December 1940 171 iv CONTENTS 8. A Tightening Noose: December 1940–June 1941 200 9. The Eastern Onslaught: June 1941– September 1941 229 10. The “Final Solution”: September 1941– December 1941 259 PART THREE : SHOAH (January 1942–May 1945) 11. Total Extermination: January 1942–June 1942 287 12. Total Extermination: July 1942–March 1943 316 13. Total Extermination: March 1943–October 1943 345 14. Total Extermination: Fall 1943–Spring 1944 374 15. The End: March 1944–May 1945 395 Notes 423 Selected Bibliography 449 Index 457 About the Author About the Abridger Other Books by Saul Friedlander Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher FOREWORD his abridged edition of Saul Friedländer’s two volume his- Ttory of Nazi Germany and the Jews is not meant to replace the original. Ideally it should encourage its readers to turn to the full-fledged version with its wealth of details and interpre- tive nuances, which of necessity could not be rendered here. -

Shelter from the Holocaust

Shelter from the Holocaust Shelter from the Holocaust Rethinking Jewish Survival in the Soviet Union Edited by Mark Edele, Sheila Fitzpatrick, and Atina Grossmann Wayne State University Press | Detroit © 2017 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of Amer i ca. ISBN 978-0-8143-4440-8 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-8143-4267-1 (paper) ISBN 978-0-8143-4268-8 (ebook) Library of Congress Control Number: 2017953296 Wayne State University Press Leonard N. Simons Building 4809 Woodward Ave nue Detroit, Michigan 48201-1309 Visit us online at wsupress . wayne . edu Maps by Cartolab. Index by Gillespie & Cochrane Pty Ltd. Contents Maps vii Introduction: Shelter from the Holocaust: Rethinking Jewish Survival in the Soviet Union 1 mark edele, sheila fitzpatrick, john goldlust, and atina grossmann 1. A Dif er ent Silence: The Survival of More than 200,000 Polish Jews in the Soviet Union during World War II as a Case Study in Cultural Amnesia 29 john goldlust 2. Saved by Stalin? Trajectories and Numbers of Polish Jews in the Soviet Second World War 95 mark edele and wanda warlik 3. Annexation, Evacuation, and Antisemitism in the Soviet Union, 1939–1946 133 sheila fitzpatrick 4. Fraught Friendships: Soviet Jews and Polish Jews on the Soviet Home Front 161 natalie belsky 5. Jewish Refugees in Soviet Central Asia, Iran, and India: Lost Memories of Displacement, Trauma, and Rescue 185 atina grossmann v COntents 6. Identity Profusions: Bio- Historical Journeys from “Polish Jew” / “Jewish Pole” through “Soviet Citizen” to “Holocaust Survivor” 219 john goldlust 7.