Power Production and Regulatory Reform: Easing the Transition to an Economic Energy Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tva-Final-Integrated-Resource-Plan-Eis-Volume-1.Pdf

Integrated Resource Plan 2015 FINAL SUPPLEMENTAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT VOLUME 1 - MAIN TEXT TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY Integrated Resource Plan Document Type: EIS – Administrative Record Index Field: Final Environmental Impact Statement Project Name: Integrated Resource Plan Project Number: 2014-2 Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement July 2015 Proposed action: Integrated Resource Plan Lead agency: Tennessee Valley Authority For further information on the EIS, For further information on the project, contact: contact: Charles P. Nicholson Gary S. Brinkworth NEPA Compliance Integrated Resource Plan Project Manager Tennessee Valley Authority Tennessee Valley Authority 400 W. Summit Hill Drive, WT 11D 1101 Market St., MR 3K-C Knoxville, Tennessee 37902 Chattanooga, TN 47402 Phone: 865-632-3582 Phone: 423-751-2193 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) proposes to update its 2011 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) to determine how it will meet the electrical needs of its customers over the next 20 years and fulfill its mission of low-cost, reliable power, environmental stewardship and economic development. Planning process steps included: 1) determining the future need for power; 2) identifying potential supply-side options for generating power and demand- side options for reducing the need for power; 3) developing a range of planning strategies encompassing different approaches, targets and emphasized resources; and 4) identifying a range of future conditions (scenarios) used -

NRC Collection of Abbreviations

I Nuclear Regulatory Commission c ElLc LI El LIL El, EEELIILE El ClV. El El, El1 ....... I -4 PI AVAILABILITY NOTICE Availability of Reference Materials Cited in NRC Publications Most documents cited in NRC publications will be available from one of the following sources: 1. The NRC Public Document Room, 2120 L Street, NW., Lower Level, Washington, DC 20555-0001 2. The Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, P. 0. Box 37082, Washington, DC 20402-9328 3. The National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161-0002 Although the listing that follows represents the majority of documents cited in NRC publica- tions, it is not intended to be exhaustive. Referenced documents available for inspection and copying for a fee from the NRC Public Document Room include NRC correspondence and internal NRC memoranda; NRC bulletins, circulars, information notices, inspection and investigation notices; licensee event reports; vendor reports and correspondence; Commission papers; and applicant and licensee docu- ments and correspondence. The following documents in the NUREG series are available for purchase from the Government Printing Office: formal NRC staff and contractor reports, NRC-sponsored conference pro- ceedings, international agreement reports, grantee reports, and NRC booklets and bro- chures. Also available are regulatory guides, NRC regulations in the Code of Federal Regula- tions, and Nuclear Regulatory Commission Issuances. Documents available from the National Technical Information Service Include NUREG-series reports and technical reports prepared by other Federal agencies and reports prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission, forerunner agency to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Documents available from public and special technical libraries include all open literature items, such as books, journal articles, and transactions. -

A Comparative Analysis of Nuclear Facility Siting Using Coalition Opportunity Structures and the Advocacy Coalition Framework

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ORDER IN A CHAOTIC SUBSYSTEM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF NUCLEAR FACILITY SITING USING COALITION OPPORTUNITY STRUCTURES AND THE ADVOCACY COALITION FRAMEWORK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By KUHIKA GUPTA Norman, Oklahoma 2013 ORDER IN A CHAOTIC SUBSYSTEM: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF NUCLEAR FACILITY SITING USING COALITION OPPORTUNITY STRUCTURES AND THE ADVOCACY COALITION FRAMEWORK A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BY ______________________________ Dr. Hank C. Jenkins-Smith, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Carol L. Silva, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Christopher M. Weible ______________________________ Dr. Deven E. Carlson ______________________________ Dr. Jill A. Irvine © Copyright by KUHIKA GUPTA 2013 All Rights Reserved. Dedication For my incredible parents, Anil and Alpana Gupta, for making all of this possible, and my husband, Joseph T. Ripberger, for being a constant inspiration. Acknowledgements This dissertation would not be possible were it not for the invaluable support I have received throughout my journey as an undergraduate at Delhi University in India, a graduate student at the University of Warwick in England, and my pursuit of a doctorate at the University of Oklahoma in the United States. During my time at Delhi University, Ramu Manivannan was an amazing mentor who taught me the value of making a difference in both academia and the real world. My greatest debt is to Hank Jenkins-Smith and Carol Silva at the University of Oklahoma, whose encouragement, guidance, and intellectual advice has made this journey possible. I am deeply grateful for their unending support; this dissertation would not exist without them. -

Degradation of Fuel Oil Flow to the Emergency Diesel Generator

UNITED STATES REG~kq)~ 0 NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION REGION II 230 PEACHTREE STREET, N.W. SUITE 1217 ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30303 ~*3 DEC 1 1977 In Reply Refer To: RII:JPO 50-438, 50-439 50-259, 50-260 50-296, 50-518 50-519, 50-520 50-521, 50-553 50-554, 50-327 50-328w 50-391, 7U75V6' 50-567 Tennessee Valley Authority Attn: Mr. Godwin Williams, Jr. Manager of Power 830 Power Building Chattanooga, Tennessee 37401 Gentlemen: The enclosed IE Circular No. 77-15 is forwarded to you for information. No written response is required. Should you have any questions related to your understanding of this matter, please contact this office. Sincerely, James P. 0 eilly Director Enclosures: 1. IE Circular No. 77-15 2. List of IE Circulars Issued in 1977 cc: J. E. Gilleland Assistant Manager of Power 830 Power Building Chattanooga, Tennessee 37401 / 2-- ~q,) Tennessee Valley Authority -2- W. W. Aydelott, Project Manager Bellefonte Nuclear Plant P. 0. Box 2000 Hollywood, Alabama 35752 Stan Duhan 400 Commerce Street E4D112 Knoxville, Tennessee 37902 J. G. Dewease, Plant Superintendent Box 2000 Decatur, Alabama 35602 R. T. Hathcote, Project Manager Hartsville Nuclear Plant P. 0. Box 2000 Hartsville, Tennessee 37074 G. G. Stack, Project Manager Sequoyah Nuclear Plant P. 0. Box 2000 Daisy, Tennessee 37319 J. M. Ballentine Plant Superintendent Sequoyah Nuclear Plant P. 0. Box 2000 Daisy, Tennessee 37319 T. B. Northern, Jr. Project Manager Watts Bar Nuclear Plant P. 0. Box 2000 Spring City, Tennessee 37381 UNITED STATES NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION OFFICE OF INSPECTION AND ENFORCEMENT WASHINGTON D.C. -

Sequoyah Nuclear Plant Comprehensive Schedule

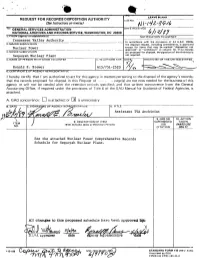

'. LEAVE BLANK . REQUEST FOR RECORDS DISPOSITION AUTHORITY JUB.' NO. (See Instructions on reverse) tJ ///L/z-ftf-,I? ~TO~:-G--E-N-E-R-A-L-S-E-R-V-I-C-E-S-A-D-M~IN-I-S-T-R-A-T-IO-N--------------------------~D~AC~T~E~R~E~CEIV_ED /_ J~ ~_I p~ NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE, WASHINGTON, DC 20408 ~ /1 q fJ / 1. FROM (Aeency or establishment) NOTI FICATION -T-=-O-A~G-:-E::cN-C-:-Y,.,----- --------------------._-------------- Tennessee Valley Authority In accordance with the provisions of 44 U.S.C, 3303a ~2.~M~A~J~O~R~S~u~e~D~lv~I~S~IO~N~-----------~--------------------------------- the disposal request, including amendments, is approved except for items that may be marked "disposition not Nuclear Power approved" or "withdrawn" in column 10. If no records -=-3.--:M-"""'1N"""O""'R=-=s""u=e=D"77 V"'"'Ic-=S"""IO""'N,..,----------------------·--------- - --- --- ---- -- - ---- 1 are proposed for disposal, the signatureof the Archivist is Sequoyah Nuclear Plant not required. 4. NAME OF PERSON WITH WHOM TO CONFER 5~TELEPHONE EXT. ARCHIVIST OF THE UNITED STATES \ Ronald E. Brewer 615/751 2520 6. CERTIFICATE OF AGENCY REPRESENTATIVE I hereby certify that I am authorized to act for this agency in matters pertaining to the disposal of the agency's records; that the records proposed for disposal in this Hequest of __ _ _ __paqets) are not now needed for the business of this agency or will not be needed after the retention periods specified; and that written concurrence from the General Accounting Office, if required under the provisions of Title 8 of the GAU Manual tor Guidance of Federal Agencies, is attached. -

Educational and Promotional Films

LEAVE BLANK REQUEST FOR RECORDS DISPOSITION AUTHORITY • JOB NO (See Instructions on reverse) iJ I --/Lfl- ~~1'~(p TO: GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION DATE RECEIVEO NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE, WASHINGTON, DC 20408 /t-/It; - ff' 1. F ROM (A,~nc)' or ~atabli'hment) NOTIFICATION TO AGENCY Tennessee Valley Authority In accordance with the provisions of 44 U.S.C. 3303a 2. MAJOR SUBDIVISION the disposal request. including amendments. is approved Governmental and Public Affairs except for Items that may be marked "disposition not approved" or "withdrawn" in column 10. If no records 3. MINOR SUBOIVISION are proposed for dlsoosal. the signature of the Archivist is Media Relations not required. 4, NAME OF PERSONWITH WHOM TO CONFER 5, TELEPHONE EXT. ARCHIVIST OF THE UNITED STATES _~C~ C Ronald E. Brewer 615/751-2520 Z ;:;D ~~ 10 6. CERTIFICATE OF AGENCY REPRESENTATIVE I I hereby certify that I am authorized to act for this agency in matters pertaining to the disposal of the agency's records; that the records proposed for disposal in this Request of page(s) are not now needed for the businessof this agency or will not be needed after the retention periods specified; and that written concurrence from the General Accounting Office, if required under the provisions of Title 8 of the GAO Manual for Guidance of Federal Agencies, is attached. A. GAO concurrence: D is attached; or [!] is unnecessary. B. DATE C. SIGNATURE OF AGENCY REPRESENTATIVE D. TITLE Assistant TVA Archivist 9. GRS OR 10. ACTION SUPERSEDED TAKEN ITEM (With Inc/u.ive Datet or RetenHon Period.) JOB (NARSUSE NO. -

20080418 Oyster Creek Motion for New Contentions Re Fatigue

April 18, 2008 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION BEFORE THE COMMISSION ________________________________________________ In the Matter of ) ) AMERGEN ENERGY COMPANY, LLC ) Docket No. (Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station) ) 50-219-LR __________________________________________ ) MOTION BY NUCLEAR INFORMATION AND RESOURCE SERVICE; JERSEY SHORE NUCLEAR WATCH, INC.; GRANDMOTHERS, MOTHERS AND MORE FOR ENERGY SAFETY; NEW JERSEY PUBLIC INTEREST RESEARCH GROUP; NEW JERSEY SIERRA CLUB; AND NEW JERSEY ENVIRONMENTAL FEDERATION TO REOPEN THE RECORD AND FOR LEAVE TO FILE A NEW CONTENTION, AND PETITION TO ADD A NEW CONTENTION Submitted by: Richard Webster Eastern Environmental Law Center 744 Broad Street, Suite 1525 Newark, NJ 07102-3094 Counsel for Nuclear Information And Resource Service; Jersey Shore Nuclear Watch, Inc.; Grandmothers, Mothers And More For Energy Safety; New Jersey Public Interest Research Group; New Jersey Sierra Club; New Jersey Environmental Federation TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ................................................................................................1 NEW INFORMATION AVAILABLE........................................................................................2 ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................................4 I. The Commission Should Hear This Motion ..........................................................................4 II. The Record Must Be Reopened.............................................................................................5 -

Public Preferences Related to Consent-Based Siting Of

Public Preferences Related to Consent-Based Siting of Radioactive Waste Management Facilities for Storage and Disposal: Analyzing Variations over Time, Events, and Program Designs Prepared for US Department of Energy Nuclear Fuel Storage and Transportation Planning Project Hank C. Jenkins-Smith Carol L. Silva Kerry G. Herron Kuhika G. Ripberger Matthew Nowlin Joseph Ripberger Center for Risk and Crisis Management, University of Oklahoma Evaristo “Tito” Bonano Rob P. Rechard Sandia National Laboratories February 2013 FCRD-NFST-2013-000076 SAND 2013-0032P Public Preferences Related to Consent Based Siting of Radioactive Waste Management Facilities ii February 2013 DISCLAIMER This information was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the U.S. Government. Neither the U.S. Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness, of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. References herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trade mark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the U.S. Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U.S. Government or any agency thereof. Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-program laboratory managed and operated by Sandia Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Lockheed Martin Corporation, for the US Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. -

Answer in Opposition to California PIRG 840608 Request For

~' _ ,. 1 .. - I" 7/13/84 , | ' UNITED STATES OF AMERICA NUCLEAR REG'? ATORY COMMISSION $p BEFORE THE ATOMIC SAFETY AND LICENSING BOARD' .84 k g3 - P2:47 ' In the Matter of - ) y_ , y.. } 4:; ;,. Docket No. 50-70-01.R. d,.- GENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANY ) '' * ). (GETR Vallecitos) ') . ' NRC STtFF'S ANSWER TO CALPIRG'S' REQUEST FOR READMISS10K 10 PROCEEDINGS , . .- . , , On June 8,1984, Mr. Glenn Barlotfile(I an unsigned pleading enti- tied " Petitioners /In'tervenor'slRequest for Readmission to Proceedings" ~ ("Reqdest") Ton behalf of the C'alifornia Public Interest Research Group, ._ .. Santa Cruz office ("C'alPIRG"-). In its Request, CalPIRG asserts that it ' had previously established standing in_this proceeding in 1970, but that its petition was dismissed in 1983 without CalPIRG being " informed" of this decision "until very recently." CalPIRG further asserts as follows:_ This past week our' State Board first learned about the NRC's renewed interest in relicensing the_GETR reactor in Alcmeda County, after a lapse of nearly. seven years, and our Board "oten unanimously'to ' -continue C'alPIRG's participe ion in this proceed- ' ing . For the reasons set forth below, the NRC Staf# T W P ) opposes CalPIRG's , Request and recommends that.it be denied.' _ BACKGROUND On September 15, 1977, notice was published in the Federal Register indicating that the Commission was considering the applications file 6 by 8407240313 840713 i PDR ADOCK 05000070 G PDR O QS/ J . -2- General Electric Company ("GE") for renewal of SNM License No. SNM-960, and Operating License No. TR-1 for the General Electric Test Reactor (GETR) located at the Vallecitos Nuclear Center.1/ The notice further indicated that any persons whose interests might be affected by these proceedings may file a petition for leave to intervene in accordance with 10 C.F.R. -

FOD-75-11 Examination of Financial Statements of the Tennessee Valley

REPQRT TO THE CONGRESS I11111111lllllIllIll11 111111111111111111111111 Ill1 LM097068 Examination Of Financial Statements Of The Tennessee Valley Authority For Fiscal Year 1974 BY THE COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES FOD-75-1 1 COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON. D.C. PO5448 B-114850 To the President of the Senate and the c! Speaker of the House of Representatives /' This is our report on the examination of the Tennessee Valley Authority's financial statements for fiscal year 1974, pursuant to the Government Corporation Control Act (31 U.S.C. 851). We are sending copies of this report to the Director, Of- fice of Management and Budget; the Secretary of the Treasury; and the Chairman, Board of Dir ey Authority. Comptroller General of the United States Contents Page DIGEST i CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 GENERAL COMMENTS ON PROGRAMS AND ACTIVITIES 2 Power program 2 Operating results 2 Rate adjustments 4 Proprietary capital and payments to the Treasury 5 Borrowing authority 7 Construction activities 8 Coal procurement 12 Fertilizer program 18 Developmental production 19 Other matters 20 3 SCOPE OF EXAMINATION 22 4 OPINION ON FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 23 EXHIBIT I Balance sheets, June 30, 1974 and 1973 24 II Power program, net income and retained earnings for the years ended June 30, 1974 and 1973 26 III Nonpower programs, net expense and accumu- lated net expense for the years ended June 30, 1974 and 1973 27 IV Changes in financial position for the years ended June 30, 1974 and 1973 29 Notes to financial statements 31 SCHEDULE -

Qu Osoltjrc NUREG-1872, Vol

qU oSoLTJRC NUREG-1872, Vol. 2 United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission ProtectingPeople and the Environment HudcD [jE©wftamfsýýpc Wafm(M oran EA Office of New Reactors AVAILABILITY OF REFERENCE MATERIALS IN NRC PUBLICATIONS NRC Reference Material Non-NRC Reference Material As of November 1999, you may electronically access Documents available from public and special technical NUREG-series publications and other NRC records at libraries include all open literature items, such as NRC's Public Electronic Reading Room at books, journal articles, and transactions, Federal http:t/www.nrc..ov/reading-rm.html. Register notices, Federal and State legislation, and Publicly released records include, to name a few, congressional reports. Such documents as theses, NUREG-series publications; Federal Register notices; dissertations, foreign reports and translations, and applicant, licensee, and vendor documents and non-NRC conference proceedings may be purchased correspondence; NRC correspondence and internal from their sponsoring organization. memoranda; bulletins and information notices; inspection and investigative reports; licensee event reports; and Commission papers and their Copies of industry codes and standards used in a attachments. substantive manner in the NRC regulatory process are maintained at- NRC publications in the NUREG series, NRC The NRC Technical Library regulations, and Title 10, Energy, in the Code of Two White Flint North FederalRegulations may also be purchased from one 11545 Rockville Pike of these two sources. Rockville, MD 20852-2738 1. The Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Mail Stop SSOP These standards are available in the library for Washington, DC 20402-0001 reference use by the public. Codes and standards are Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov usually copyrighted and may be purchased from the Telephone: 202-512-1800 originating organization or, if they are American Fax: 202-512-2250 National Standards, from- 2. -

A Study of the Cherokee Nuclear Station: Projected Impacts, Monitoring Plan, and Mitigation Options for Cherokee County, South Carolina

QRNL/TM-6804 .V A Study of the Cherokee Nuclear Station: Projected Impacts, Monitoring Plan, and Mitigation Options for Cherokee County, South Carolina Elizabeth Peelle Martin Schweitzer Philip Scharre Bradford Pressman t \ .« vkJJSJ."* V OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY OPERATED BY UNION CARBIDE CORPORATION • FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY BLANK PAGE 0RNL/TM-68CI4 Contract No. W-7405-eng-26 A STUDY OF THE CHEROKEE NUCLEAR STATION: PROJECTED IMPACTS, MONITORING PLAN, AND MITIGATION OPTIONS FOR CHEROKEE COUNTY, SOUTH CAROLINA Elizabeth Peelle Martin Schweitzer Philip Scharre* Bradford Pressmant Energy Division Oak Ridge National Laboratory -NOTICE- TWa upon WU prepared a a» account of wortt Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37830 spooKfcd by the United Statea Government. Neither the United Sutea not the United Statei Department of Energy, nor any of their employees, nor any of theli contractor*, niheontneton, or their employees, makei any warranty, expma or implied, 01 aammn any legal liability or KaponHbUlty for the accuncy.compleuntti oe uiefuhMia of any information, appantua, product or procea diacloaed, or repttBnls that Ita ine would not infringe privately owned rlftxtt. Date Published: July 1979 * Graduate School of Planning, University of Tennessee, Knoxville +Denison University, Granville, Ohio OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37830 operated by UNION CARBIDE CORPORATION for the DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY ]& CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES vi LIST OF TABLES vii ABSTRACT xi 1. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 2. SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC PROFILE