Mujib--Language of Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane

Indian Foreign Affairs Journal Vol. 4, No. 3, July - September, 2009, 102-117 ORAL HISTORY Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane Arundhati Ghose, often acclaimed for espousing wittily India’s nuclear non- proliferation policy, narrates the events associated with an assignment during her early diplomatic career that culminated in the birth of a nation – Bangladesh. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal (IFAJ): Thank you, Ambassador, for agreeing to share your involvement and experiences on such an important event of world history. How do you view the entire episode, which is almost four decades old now? Arundhati Ghose (AG): It was a long time ago, and my memory of that time is a patchwork of incidents and impressions. In my recollection, it was like a wave. There was a lot of popular support in India for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his fight for the rights of the Bengalis of East Pakistan, fund-raising and so on. It was also a difficult period. The territory of what is now Bangladesh, was undergoing a kind of partition for the third time: the partition of Bengal in 1905, the partition of British India into India and Pakistan and now the partition of Pakistan. Though there are some writings on the last event, I feel that not enough research has been done in India on that. IFAJ: From India’s point of view, would you attribute the successful outcome of this event mainly to the military campaign or to diplomacy, or to the insights of the political leadership? AG: I would say it was all of these. -

In East Pakistan (1947-71)

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), Vol. 63(1), 2018, pp. 59-89 THE INVISIBLE REFUGEES: MUSLIM ‘RETURNEES’ IN EAST PAKISTAN (1947-71) Anindita Ghoshal* Abstract Partition of India displaced huge population in newly created two states who sought refuge in the state where their co - religionists were in a majority. Although much has been written about the Hindu refugees to India, very less is known about the Muslim refugees to Pakistan. This article is about the Muslim ‘returnees’ and their struggle to settle in East Pakistan, the hazards and discriminations they faced and policy of the new state of Pakistan in accommodating them. It shows how the dream of homecoming turned into disillusionment for them. By incorporating diverse source materials, this article investigates how, despite belonging to the same religion, the returnee refugees had confronted issues of differences on the basis of language, culture and region in a country, which was established on the basis of one Islamic identity. It discusses the process in which from a space that displaced huge Hindu population soon emerged as a ‘gradual refugee absorbent space’. It studies new policies for the rehabilitation of the refugees, regulations and laws that were passed, the emergence of the concept of enemy property and the grabbing spree of property left behind by Hindu migrants. Lastly, it discusses the politics over the so- called Muhajirs and their final fate, which has not been settled even after seventy years of Partition. This article intends to argue that the identity of the refugees was thus ‘multi-layered’ even in case of the Muslim returnees, and interrogates the general perception of refugees as a ‘monolithic community’ in South Asia. -

Competing As Lawyers

Hear students’ thoughts Forget candy, flowers. Sideravages run Disney: about how Feb. 14 What ideal gifts would 48 miles in four days. should be celebrated. you give loved ones? Sound crazy? It’s true! Read page 3. Read pages 6, 7. Read page 8. February 2018 Kennedy High School 422 Highland Avenue The Waterbury, Conn. 06708 Eagle Flyer Volume XIII, Issue V Competing Legal Eagles: Kennedy’s Mock Trial team as lawyers By Jenilyn Djan Staff Writer Win or lose...they still prevailed. Students are already contemplat- ing the 2018 season after competing at the Waterbury Courthouse Thurs- day Dec. 7, 2017 for the Mock Trial Regional competition, where students practiced a semi-altered case mimick- ing an actual trial about whether a man was guilty for the deaths of four fam- ily members aboard his ship. Students won their defense while the prosecu- tion side lost. “It was a good season, even though I was just an alternate. I was able to learn a lot this year,” Melany Junco, a sophomore. Students have been practicing since August 29, 2017 once a week every Monday for this competition, and have even done a few Saturday and addi- LEGAL EAGLES tional practice sessions to be more pre- The defense side of the team won vance to the next round next season. Kennedy’s Mock Trial team competed at the Waterbury Court Thursday, Dec. 7, 2017. They won one case and lost another. Members are, their case, but the prosecution lost. “Our team worked really hard this pared. front row, left to right: sophomores Nadia Evon, Melany Junco, juniors Risper “Even though we lost at the com- “Even though we lost, I thought our year and next year we’ll work even Githinji, Jenilyn Obuobi-Djan, Derya Demirel, Marin Delaney, Kaitlyn Giron, and petition, the students did great,” said prosecution did great,” said Kariny harder to advance,” said William sophomore Samarah Brunette. -

Students, Space, and the State in East Pakistan/Bangladesh 1952-1990

1 BEYOND LIBERATION: STUDENTS, SPACE, AND THE STATE IN EAST PAKISTAN/BANGLADESH 1952-1990 A dissertation presented by Samantha M. R. Christiansen to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts September, 2012 2 BEYOND LIBERATION: STUDENTS, SPACE, AND THE STATE IN EAST PAKISTAN/BANGLADESH 1952-1990 by Samantha M. R. Christiansen ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate School of Northeastern University September, 2012 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the history of East Pakistan/Bangladesh’s student movements in the postcolonial period. The principal argument is that the major student mobilizations of Dhaka University are evidence of an active student engagement with shared symbols and rituals across time and that the campus space itself has served as the linchpin of this movement culture. The category of “student” developed into a distinct political class that was deeply tied to a concept of local place in the campus; however, the idea of “student” as a collective identity also provided a means of ideological engagement with a globally imagined community of “students.” Thus, this manuscript examines the case study of student mobilizations at Dhaka University in various geographic scales, demonstrating the levels of local, national and global as complementary and interdependent components of social movement culture. The project contributes to understandings of Pakistan and Bangladesh’s political and social history in the united and divided period, as well as provides a platform for analyzing the historical relationship between social movements and geography that is informative to a wide range of disciplines. -

EWU Celebrates 17Th Convocation

VOL-XVIII.ISSUE-I .SPRING-2018 EWU Celebrates 17th Convocation A large portion of our society is university authority for fulfilling all the Trustees of EWU and former governor deprived of higher education. regulatory conditions and achieving the of Bangladesh Bank, Dr. Mohammed Therefore, the Education Minister permanent Sanad. A total of 1840 Farashuddin and the Vice Chancellor Nurul Islam Nahid has called on undergraduate and graduate students of the University Professor Dr. M. M. private entrepreneurs and benevolent conferred degrees and three of them Shahidul Hasan also delivered their individuals to come forward to were awarded the prestigious gold speech on the occasion. They said, that contribute in disseminating knowledge medals by the Education Minister. The the young graduates must be visionary among the people from all walks of life. medalists are Afifa Binta Saifuddin with their ideas and show patriotism in He insisted the ones who have built from Bachelor of Pharmacy, Md. Pizuar their line of work which will ensure a educational institutions must move Hossain from Master of Laws (LL.M) democratic society, free of poverty and forward with the aim to serve the and Shafayatul Islam Shiblee from terrorism. society and not to see education as a Master of Science in Applied Statistics. The members of the Board of Trustees, profitable commodity. The Minister The Convocation Speaker, Professor the Treasurer, Deans, Chairpersons of said these on 18 January 2018, Emeritus of Dhaka University, Dr. the departments, teachers, staff, Thursday afternoon while attending Anisuzzaman lamented that human graduating students and their parents the 17th Convocation of East West values are deteriorating at a fast pace all attended the Convocation Ceremony. -

Liberation War of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971 By: Alburuj Razzaq Rahman 9th Grade, Metro High School, Columbus, Ohio The Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 was for independence from Pakistan. India and Pakistan got independence from the British rule in 1947. Pakistan was formed for the Muslims and India had a majority of Hindus. Pakistan had two parts, East and West, which were separated by about 1,000 miles. East Pakistan was mainly the eastern part of the province of Bengal. The capital of Pakistan was Karachi in West Pakistan and was moved to Islamabad in 1958. However, due to discrimination in economy and ruling powers against them, the East Pakistanis vigorously protested and declared independence on March 26, 1971 under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. But during the year prior to that, to suppress the unrest in East Pakistan, the Pakistani government sent troops to East Pakistan and unleashed a massacre. And thus, the war for liberation commenced. The Reasons for war Both East and West Pakistan remained united because of their religion, Islam. West Pakistan had 97% Muslims and East Pakistanis had 85% Muslims. However, there were several significant reasons that caused the East Pakistani people to fight for their independence. West Pakistan had four provinces: Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and the North-West Frontier. The fifth province was East Pakistan. Having control over the provinces, the West used up more resources than the East. Between 1948 and 1960, East Pakistan made 70% of all of Pakistan's exports, while it only received 25% of imported money. In 1948, East Pakistan had 11 fabric mills while the West had nine. -

Positive Economic Analysis of the Constitutions - Case of Formation of the First Constitution of Pakistan

Positive Economic Analysis of the Constitutions - Case of Formation of the First Constitution of Pakistan Inaugural – Dissertation zur Erlangung der wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde des Fachbereichs Wirtschaftswissenschaften der Philipps-Universität Marburg eingereicht von: Amber Sohail (MBA aus Chakwal, Pakistan) Erstgutachter: Prof Dr. Stefan Voigt Zweitgutachter: Prof Dr.Bernd Hayo Einreichungstermin: 27. August 2012 Prüfungstermin: 25.Oktober 2012 Erscheinungsort: Marburg Hochschulkennziffer: 1180 Positive Economic Analysis of the Constitutions - Case of Formation of the First Constitution of Pakistan PhD Dissertation Department of Business Administartion and Economics Philipps-Universität Marburg Amber Sohail First Supervisor: Prof Dr. Stefan Voigt Second Supervisor: Prof Dr.Bernd Hayo Defense Date: 25.Oktober 2012 : Pakistan in 19561 1Image taken from the online resource “Story of Pakistan”. The cities marked as Lahore, Peshawar and Quetta are the provincial capitals of Punjab, NWFP and Baluchistan respectively. Karachi was the provincial capital of Sind as well as the capital of Pakistan in 1956. The silver line at the top of West Pakistan demaracates the disputed area, Kashmir. East Pakistan laid across India and had Dacca/Dhaka as the provincial capital. 3 Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank my supervisor and mentor Professor Stefan Voigt for all the guidance that he provided. After 3 years of research when I look back at my initial documents, they seem embarrassingly inadequate and I once again marvel at the patience he showed while reading them. He not only read those documents but appreciated and encouraged me every step of the way. His guidance was so complete that I was able to finish my project in time and in a satisfactory manner despite many odds. -

Disease and Death: Issues of Public Health Among East Bengali Refugees in 1971 -Utsa Sarmin

Disease and Death: Issues of Public Health Among East Bengali Refugees in 1971 -Utsa Sarmin Introduction: “Because of 'Operation Searchlight', 10 million refugees came to India, most of them living in appalling conditions in the refugee camps. I cannot forget seeing 10 children fight for one chapatti. I cannot forget the child queuing for milk, vomiting, collapsing and dying of cholera. I cannot forget the woman lying in the mud, groaning and giving birth.”1 The situation of East Bengali refugees in 1971 was grim. The Bangladesh liberation war of 1971 witnessed 10 million people from the erstwhile East Pakistan (present Bangladesh), fleeing the persecution by Pakistani soldiers and coming to India seeking refuge2. The sudden influx of refugees created a mammoth humanitarian crisis. At one hand, the refugees were struggling to access food, water, proper sanitation, shelter. On the other hand, their lives were tormented by various health issues. The cholera epidemic of 1971 alone killed over 5,000 refugees.3 Other health concerns were malnutrition, exhaustion, gastronomical diseases. “A randomized survey on refugee health highlights the chief medical challenges in the refugee population as being malnutrition, diarrhoea, vitamin-A deficiency, pyoderma, and tuberculosis.”4 The Indian government was not adequately equipped to deal with a crisis of such level. Even though there was initial sympathies with the refugees, it quickly waned and by May 1971, the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi characterized it as a “national problem”5 and by July, she described the problem could potentially threaten the peace of South Asia.6 The proposed research paper will look into the public health crisis and the rate of mortality due to the crisis among the refugees of West Bengal in 1971. -

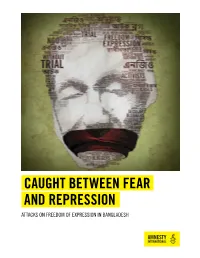

Caught Between Fear and Repression

CAUGHT BETWEEN FEAR AND REPRESSION ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN BANGLADESH Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover design and illustration: © Colin Foo Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 13/6114/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION TIMELINE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & METHODOLOGY 6 1. ACTIVISTS LIVING IN FEAR WITHOUT PROTECTION 13 2. A MEDIA UNDER SIEGE 27 3. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW 42 4. BANGLADESH’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK 44 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 Glossary AQIS - al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent -

THE DECLINE of the MUSLIM L,EAGUE and the ASCENDANCY of the BUREAUCRACY in EAST PAKISTAN 1947-54

THE DECLINE OF THE MUSLIM l,EAGUE AND THE ASCENDANCY OF THE BUREAUCRACY IN EAST PAKISTAN 1947-54 A H AITh1ED KAMAL JANUARY 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF THE AUSTRALL.\N NATIONAL UNIVERSITY 205 CHAPTER 7 POLICE, PEOPLE, AND PROTEST I The Muslim League's incapacity to control the police force and its eventual dependence on them as the mainstay of state power introduced tensions into the League itself; in addition, it directly contributed to certain developments in the realm of politics. I also intend to highlight in this chapter instances where the police could not be controlled by civil bureaucrats and magistrates. Much of the erosion of the legitimacy of the Muslim League rule in East Pakistan was caused by the brutality, unlicensed tyranny, and corruption of the police. The press and the members of the Opposition in the East Bengal Legislative Assembly on many occasions exposed police atrocities on the population in a language that quite often verged on sentimentality. The Muslim League leadership in government explained police atrocities in terms of inexperience and indiscipline of the force. But people refused to see the regime as something different in intent and purpose from the police actions . Indeed, people's interpretation of 'political independence' did not fit well with what the ' police called 'law and order', and as a result a number of serious clashes occured. Police power was liberally employed to sustain the Muslim League rule; as a result 'police excesses' occurred at a regular rate. In a propaganda tract on the six years of Muslim League rule in East Pakistan that the United Front circulated at the time of the March 1954 election , cases of police atrocities featured prominently and the League was called a 'Murderer' .1 It was, in fact, the Front's pledge to limit police power that inspired the people to vote for the United Front in the first general election in the province. -

Mirpur Bangla School and College (Girls Section), Mirpur 6, Dhaka €“ 1216 Roll No: 14001 - 15000

Mirpur Bangla School and College (Girls Section), Mirpur 6, Dhaka – 1216 Roll No: 14001 - 15000 Name Email Father Name Roll No BULBUL AHAMED [email protected] MD. ALTAF HOSSAIN 14001 MD. OSMAN GANI [email protected] MD.NURUL ISLAM 14002 MD.OSMAN AKOND [email protected] Md. Sultan Akond 14003 Md. Osman Goni [email protected] Md.Mhasin Molla 14004 Md.Osman Gony [email protected] Md.Sober Ali 14005 MD. OSMAN GANI SHAMIM [email protected] MOHAMMAD HOSSAIN 14006 MD. Osman Mia [email protected] Md. Osman Mia 14007 Anindita Das [email protected] Ashok Kumar Das 14008 MD.OVHIB-IQBAL [email protected] MD.SHOEB 14009 Shake Shohanur Rahaman Ripon [email protected] Shake Rafiqul Islam 14010 EHSANUL HUQ CHOUDHURY [email protected] MAHBUBUL HUQ CHOUDHURY 14011 Wahida Nahid [email protected] Monjur Hossain Sraker 14012 S.M.Mushfiqur Rahman [email protected] S.M.Mahbub-Ur-Rahman 14013 Asma Rahaman [email protected] Azizur Rahaman 14014 MITHUN KUMAR HORH [email protected] Shameresh Chandro Horh 14015 Pabaan Debnath [email protected] Nemailal Debnath 14016 Syed Salah Uddin. [email protected] Syed Moin Uddin. 14017 Md.Tahiduzzaman [email protected] Md.Bazlur Rahman Moral 14018 Sanjoy Pal [email protected] Santosh Pal 14019 MOLLA PALAS AHMED [email protected] MOLLA PALAS AHMED 14020 Md Mahbubul Hoque [email protected] Md Zahurul Hoque 14021 Palash Chandra Sarkar [email protected] Ganesh Chandra Sarkar 14022 Hazrat Ali [email protected] RAHMAT ALI GAZI 14023 MD. PALASH MIAH [email protected] Md. -

Sample Statements Bengali Hindu Genocide 2021

1971 BENGALI HINDU GENOCIDE DRAFT STATEMENTS FOR ELECTED OFFICIALS DRAFT 1 I join with my Bengali Hindu constituents to honor and commemorate the tragedy that befell their people 50 years ago. The 1971 Bengali Hindu Genocide was one of the worst human tragedies of the 20th century and sadly is one of the few unrecognized or forgotten genocides. On March 25, 1971, the Pakistani Army launched an offensive called ‘Operation Searchlight’ into East Pakistan, present-day Bangladesh, thus beginning the 10-month genocidal campaign. Over that time, approximately 2-3 million people were killed, over 200,000 women were raped in organized rape camps, and over 10 million people were displaced, most finding refuge in India. But don’t just take it from me. Here are the words of the late U.S. Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA) who visited the refugee camps in India in 1971 as the genocide was unfolding in neighboring Bangladesh. On the floor of the U.S. Senate on November 7, 1971 Senator Kennedy said, “Field reports to the U.S. Government, countless eye-witness journalistic accounts, reports of International agencies such as [the] World Bank and additional information available to the subcommittee document the reign of terror which grips East Bengal (East Pakistan). Hardest hit have been members of the Hindu community who have been robbed of their lands and shops, systematically slaughtered, and in some places, painted with yellow patches marked ‘H’. All of this has been officially sanctioned, ordered and implemented under martial law from Islamabad.” I ask my colleagues to join me, the Bengali Hindu diaspora, and human rights activists around the world in remembering the tragic events of the 1971 Bengali Hindu Genocide so that we and the world may never forget.