Abstention in the Time of Ferguson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Society of Barristers Quarterly

International Society of Barristers Volume 52 Number 2 ATTICUS FINCH: THE BIOGRAPHY—HARPER LEE, HER FATHER, AND THE MAKING OF AN AMERICAN ICON Joseph Crespino TAMING THE STORM: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JUDGE FRANK M. JOHNSON JR. AND THE SOUTH’S FIGHT OVER CIVIL RIGHTS Jack Bass TOMMY MALONE: THE GUIDING HAND SHAPING ONE OF AMERICA’S GREATEST TRIAL LAWYERS Vincent Coppola THE INNOCENCE PROJECT Barry Scheck Quarterly Annual Meetings 2020: March 22–28, The Sanctuary at Kiawah Island, Kiawah Island, South Carolina 2021: April 25–30, The Shelbourne Hotel, Dublin, Ireland International Society of Barristers Quarterly Volume 52 2019 Number 2 CONTENTS Atticus Finch: The Biography—Harper Lee, Her Father, and the Making of an American Icon . 1 Joseph Crespino Taming the Storm: The Life and Times of Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. and the South’s Fight over Civil Rights. 13 Jack Bass Tommy Malone: The Guiding Hand Shaping One of America’s Greatest Trial Lawyers . 27 Vincent Coppola The Innocence Project . 41 Barry Scheck i International Society of Barristers Quarterly Editor Donald H. Beskind Associate Editor Joan Ames Magat Editorial Advisory Board Daniel J. Kelly J. Kenneth McEwan, ex officio Editorial Office Duke University School of Law Box 90360 Durham, North Carolina 27708-0360 Telephone (919) 613-7085 Fax (919) 613-7231 E-mail: [email protected] Volume 52 Issue Number 2 2019 The INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF BARRISTERS QUARTERLY (USPS 0074-970) (ISSN 0020- 8752) is published quarterly by the International Society of Barristers, Duke University School of Law, Box 90360, Durham, NC, 27708-0360. -

The Role of Politics in Districting the Federal Circuit System

PUSHING BOUNDARIES: THE ROLE OF POLITICS IN DISTRICTING THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT SYSTEM Philip S. Bonforte† I. Introduction ........................................................................... 30 II. Background ............................................................................ 31 A. Judiciary Act of 1789 ......................................................... 31 B. The Midnight Judges Act ................................................... 33 C. Judiciary Act of 1802 ......................................................... 34 D. Judiciary Act of 1807 ....................................................... 344 E. Judiciary Act of 1837 ....................................................... 355 F. Tenth Circuit Act ................................................................ 37 G. Judicial Circuits Act ........................................................... 39 H. Tenth Circuit Act of 1929 .................................................. 40 I. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Reorganization Act of 1980 ...................................................... 42 J. The Ninth Circuit Dilemma ................................................ 44 III. The Role of Politics in Circuit Districting ............................. 47 A. The Presence of Politics ..................................................... 48 B. Political Correctness .......................................................... 50 IV. Conclusion ............................................................................. 52 † The author is a judicial clerk -

Race, Civil Rights, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Judicial Circuit

RACE, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT By JOHN MICHAEL SPIVACK A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1978 Copyright 1978 by John Michael Spivack ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In apportioning blame or credit for what follows, the allocation is clear. Whatever blame attaches for errors of fact or interpretation are mine alone. Whatever deserves credit is due to the aid and direction of those to whom I now refer. The direction, guidance, and editorial aid of Dr. David M. Chalmers of the University of Florida has been vital in the preparation of this study and a gift of intellect and friendship. his Without persistent encouragement, I would long ago have returned to the wilds of legal practice. My debt to him is substantial. Dr. Larry Berkson of the American Judicature Society provided an essential intro- duction to the literature on the federal court system. Dr. Richard Scher of the University of Florida has my gratitude for his critical but kindly reading of the manuscript. Dean Allen E. Smith of the University of Missouri College of Law and Fifth Circuit Judge James P. Coleman have me deepest thanks for sharing their special insight into Judges Joseph C. Hutcheson, Jr., and Ben Cameron with me. Their candor, interest, and hospitality are appre- ciated. Dean Frank T. Read of the University of Tulsa School of Law, who is co-author of an exhaustive history of desegregation in the Fifth Cir- cuit, was kind enough to confirm my own estimation of the judges from his broad and informed perspective. -

The Fifth Circuit Four: the Unheralded Judges Who Helped to Break Legal Barriers in the Deep South Max Grinstein Junior Divisio

The Fifth Circuit Four: The Unheralded Judges Who Helped to Break Legal Barriers in the Deep South Max Grinstein Junior Division Historical Paper Length: 2,500 Words 1 “For thus saith the Lord God, how much more when I send my four sore judgments upon Jerusalem, the sword, and the famine, and the noisome beast, and the pestilence, to cut off from it man and beast.”1 In the Bible, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are said to usher in the end of the world. That is why, in 1964, Judge Ben Cameron gave four of his fellow judges on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit the derisive nickname “the Fifth Circuit Four” – because they were ending the segregationist world of the Deep South.2 The conventional view of the civil rights struggle is that the Southern white power structure consistently opposed integration.3 While largely true, one of the most powerful institutions in the South, the Fifth Circuit, helped to break civil rights barriers by enforcing the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, something that other Southern courts were reluctant to do.4 Despite personal and professional backlash, Judges John Minor Wisdom, Elbert Tuttle, Richard Rives, and John Brown played a significant but often overlooked role in integrating the South.5 Background on the Fifth Circuit The federal court system, in which judges are appointed for life, consists of three levels.6 At the bottom are the district courts, where cases are originally heard by a single trial judge. At 1 Ezekiel 14:21 (King James Version). -

Abstention in the Time of Ferguson Contents

ABSTENTION IN THE TIME OF FERGUSON Fred O. Smith, Jr. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 2284 I. OUR FEDERALISM FROM YOUNG TO YOUNGER ........................................................ 2289 A. Our Reconstructed Federalism ...................................................................................... 2290 B. Our Reinvigorated Federalism ...................................................................................... 2293 C. Our Reparable Federalism: Younger’s Safety Valves .................................................. 2296 1. Bad Faith ................................................................................................................... 2297 2. Bias .............................................................................................................................. 2300 3. Timeliness ................................................................................................................... 2301 4. Patent Unconstitutionality ....................................................................................... 2302 D. Our Emerging “Systemic” Exception? ......................................................................... 2303 II. OUR FERGUSON IN THE TIME OF OUR FEDERALISM ............................................. 2305 A. Rigid Post-Arrest Bail .................................................................................................... 2308 B. Incentivized Incarceration............................................................................................ -

Constance Baker Motley, James Meredith, and the University of Mississippi

CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY, JAMES MEREDITH, AND THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI Denny Chin* & Kathy Hirata Chin** INTRODUCTION In 1961, James Meredith applied for admission to the University of Mississippi. Although he was eminently qualified, he was rejected. The University had never admitted a black student, and Meredith was black.1 Represented by Constance Baker Motley and the NAACP Legal De- fense and Educational Fund (LDF), Meredith brought suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi, alleging that the university had rejected him because of his race.2 Although seven years had passed since the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education,3 many in the South—politicians, the media, educators, attor- neys, and even judges—refused to accept the principle that segregation in public education was unconstitutional. The litigation was difficult and hard fought. Meredith later described the case as “the last battle of the * United States Circuit Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. ** Senior Counsel, Cadwalader, Wickersham & Taft LLP. 1. See Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343, 345–46 (5th Cir. 1962) (setting forth facts); Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696, 697–99 (5th Cir. 1962) (same). The terms “black” and “Afri- can American” were not widely used at the time the Meredith case was litigated. Although the phrase “African American” was used as early as 1782, see Jennifer Schuessler, The Term “African-American” Appears Earlier than Thought: Reporter’s Notebook, N.Y. Times: Times Insider (Apr. 21, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/times-insider/2015/04/21/ the-term-african-american-appears-earlier-than-thought-reporters-notebook/ (on file with the Columbia Law Review); Jennifer Schuessler, Use of ‘African-American’ Dates To Nation’s Earliest Days, N.Y. -

Lawyers in Love ... with Lawyers

BBarar Luncheon:Luncheon: TTuesday,uesday, FFeb.eb. 1199 IInside:nside: FFrackingracking Alt.Alt. WWellsells AAttorneyttorney sspotlight:potlight: LLarandaaranda MMoffoff eetttt WWalkeralker IInterviewnterview wwithith FFamilyamily CCourtourt LLawyersawyers inin LoveLove ...... JJudgeudge CharleneCharlene CCharletharlet DDayay wwithith LLawyersawyers Dear Chief Judge and Judges of the 19th JDC, It has come to my attention that our Court is about to approve a policy concerning the use of cellphones in our courthouse. I am told that what is being considered is that only attorneys with bar cards and court personnel will be allowed to bring a cellphone into our courthouse. On behalf of the Baton Rouge Bar Association, I request that we be allowed some input into this decision. I understand that the incident that prompted this policy decision is a person using a cellphone to video record a proceeding in a courtroom. That conduct, of course, is unacceptable. I would like to address with the Court options other than banning cellphones. I would suggest we use signs telling those in the courtroom that, if they wish to use their cellphone, they need to walk out into the hallway and that, if anyone is caught using a cellphone in the courtroom, the cellphone will be taken away and they will be held in contempt of court. The bailiff can announce this before the judge takes the bench. 2013 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Here is our concern: As you know, there are no payphones in the courthouse. Scenario 1: One of our citizens comes to our courthouse as a witness in a trial or to come to the clerk’s offi ce for some reason. -

Ideological Voting Applied to the School Desegregation Cases in the Federal Courts of Appeals from the 1960S and 1970S

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 2013 Ideological Voting Applied to the School Desegregation Cases in the Federal Courts of Appeals from the 1960s and 1970s Joseph A. Custer Case Western University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Repository Citation Custer, Joseph A., "Ideological Voting Applied to the School Desegregation Cases in the Federal Courts of Appeals from the 1960s and 1970s" (2013). Faculty Publications. 1743. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/1743 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. ARTICLES IDEOLOGICAL VOTING APPLIED TO THE SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CASES IN THE FEDERAL COURTS OF APPEALS FROM THE 1960S AND 1970S JOSEPH A. CUSTER* I. Introduction ............................................... 2 II. Legal M odel .............................................. 4 III. The Attitudinal Model .................................... 6 IV. The Personal Attributes Model............................ 9 V . The Strategic M odel ...................................... 9 V I. Ideological Voting......................................... 10 * Assistant Professor of Law and Director, Saint Louis University Law Library. Author's Note: I thank the Saint Louis University School of Law Half-Baked Faculty Workshop for much fruitful discussion that seriously helped me guide the direction of this paper. In addition, I want to thank the Central States Law Schools Association for inviting me to present this paper where I received more excellent feedback. I want to thank long- time mentor, Peter Schanck for his excellent reading of the manuscript. -

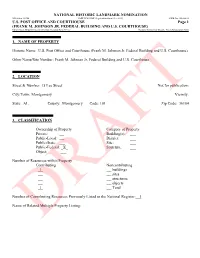

Frank M. Johnson Jr. Federal Building and US Courthouse

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 U.S. POST OFFICE AND COURTHOUSE Page 1 (FRANK M. JOHNSON JR. FEDERAL BUILDING AND U.S. COURTHOUSE) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: U.S. Post Office and Courthouse (Frank M. Johnson Jr. Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse) Other Name/Site Number: Frank M. Johnson Jr. Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 15 Lee Street Not for publication: City/Town: Montgomery Vicinity: State: AL County: Montgomery Code: 101 Zip Code: 36104 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: ___ Public-State: ___ Site: ___ Public-Federal: _X_ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 buildings sites structures objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: DRAFT NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 U.S. POST OFFICE AND COURTHOUSE Page 2 (FRANK M. JOHNSON JR. FEDERAL BUILDING AND U.S. COURTHOUSE) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Wisdom, Hon. John Minor

Published September 1999 Hon. John Minor Wisdom J By Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in 1957 (after the judge Adrienne O’Connell turned down an earlier nomination in 1953). At that time, the Fifth Circuit encompassed the states of Alabama, Flor- u Honor, courage, compassion, justice, imagina- ida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas and was tion, and wisdom. These are the six words describ- the largest circuit court in the country, in terms of both d ing Judge John Minor Wisdom which are etched geography and caseload. (It has since been split into the into the stained glass windows in the room at Tu- Fifth and Eleventh Circuits, in a move that Judge Wisdom lane Law School that was dedicated in 1998 to hold strongly opposed.) Judge Wisdom joined the court shortly g the judge’s extensive collection of legal and histori- after the U.S. Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Edu- cal books and papers. These six words describe cation, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), and Brown v. Board of Education, e qualities that have permeated the entire career of 349 U.S. 294 (1955), which ordered the implementation Judge Wisdom, a senior judge on the federal Fifth of school desegregation with “all deliberate speed.” It Circuit Court of Appeals, who is renowned for his was a difficult time to be a federal judge in the South, but s opinions on civil rights matters in the 1960s. Judge Wisdom did not falter in making unpopular deci- Judge Wisdom was born in 1905 in New Or- sions that he knew were right, and he is viewed as being leans. -

The Selma March and the Judge Who Made It Happen

6 BASS 537-560 (DO NOT DELETE) 1/7/2016 2:08 PM THE SELMA MARCH AND THE JUDGE WHO MADE IT HAPPEN Jack Bass During the violent storm that marked the Civil Rights Era that overturned the “Southern Way of Life” marked by racial segregation and the virtual removal of any participation by African-Americans in civil affairs such as voting and serving on juries that followed U.S. Supreme Court rulings at the end of the nineteenth century, no individual judge did more to restore such rights than Frank M. Johnson, Jr. on the Middle District of Alabama. Those Supreme Court cases a half-century earlier of course included Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, but also the almost unknown case of Williams v. Mississippi in 1898, and the two still little- known Giles cases from Alabama that soon followed. Essentially they gave constitutional approval for Southern states to all but eliminate African- Americans from voting. It is the historic background that provides the exceptional importance of Judge Johnson’s unprecedented order in restoring full voting rights for African-American Southerners. At thirty-seven, the youngest federal judge in the nation, Johnson called for a three-judge District Court on which he voted first in the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott case. Fifth Circuit Judge Richard Rives of Montgomery joined Johnson in a 2–1 ruling that for the first time expanded the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education beyond the issue of segregated schools. And as is well known, the outcome of that case launched the civil rights career of Dr. -

Law, Economics, and Politics: the Untold History of the Due Process

Roger Williams University Law Review Volume 17 | Issue 3 Article 3 Summer 2012 Law, Economics, and Politics: The nU told History of the Due Process Limitation on Punitive Damages Daniel W. Morton-Bentley Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR Recommended Citation Morton-Bentley, Daniel W. (2012) "Law, Economics, and Politics: The nU told History of the Due Process Limitation on Punitive Damages ," Roger Williams University Law Review: Vol. 17: Iss. 3, Article 3. Available at: http://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR/vol17/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roger Williams University Law Review by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Law, Economics, and Politics: The Untold History of the Due Process Limitation on Punitive Damages Daniel W. Morton-Bentley* I. INTRODUCTION In the 1991 case of Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Co. v. Haslip, the Supreme Court held that punitive damage awards may be constrained by the Due Process clause.' This decision spawned several sequels, all of which have been characterized as bad constitutional interpretation. 2 Commentators have critiqued these opinions' tenuous connection to the text of the Constitution and their disregard for federalism. 3 Furthermore, prior to Haslip, * LL.M, Suffolk University Law School; J.D., Roger Williams University School of Law. Thank you to Professors Jared Goldstein and Carl Bogus for their editing suggestions and advice. Thanks also to Thelma Dzialo for her research assistance and to Robert Morton-Ranney for sharing his insights into twentieth-century culture.