How Democratic Is Latvia?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LATVIA in REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30

LATVIA IN REVIEW July 26 – August 1, 2011 Issue 30 CONTENTS Government Latvia's Civic Union and New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party About 1,700 people Have Expressed Wish to Join Latvia's Newly-Founded ZRP Party President Bērziņš to Draft Legislation Defining Criteria for Selection of Ministers Parties Represented in Current Parliament Promise Clarity about Candidates This Week Procedure Established for President’s Convening of Saeima Meetings Economics Bank of Latvia Economist: Retail Posts a Rapid Rise in June Latvian Unemployment Down to 12.3% Fourteen Latvian Banks Report Growth of Deposits in First Half of 2011 European Commission Approves Cohesion Fund Development Project for Rīga Airport Private Investments Could Help in Developing Rīga and Jūrmala as Tourist Destinations Foreign Affairs Latvian State Secretary Participates in Informal Meeting of Ministers for European Affairs Cabinet Approves Latvia’s Initial Negotiating Position Over EU 2014-2020 Multiannual Budget President Bērziņš Presents Letters of Accreditation to New Latvian Ambassador to Spain Society Ministry of Culture Announces Idea Competition for New Creative Quarter in Rīga Unique Exhibit of Sand Sculptures Continues on AB Dambis in Rīga Rīga’s 810 Anniversary to Be Celebrated in August with Events Throughout the Latvian Capital Labadaba 2011 Festival, in the Līgatne District, Showcases the Best of Latvian Music Latvian National Opera Features Special Summer Calendar of Performances in August Articles of Interest Economist: “Same Old Saeima?” Financial Times: “Crucial Times for Investors in Latvia” L’Express: “La Lettonie lutte difficilement contre la corruption” Economist: “Two Just Men: Two Sober Men Try to Calm Latvia’s Febrile Politics” Dezeen magazine: “House in Mārupe by Open AD” Government Latvia's Civic Union, New Era Parties Vote to Participate in Foundation of Unity Party At a party congress on July 30, Latvia's Civic Union party voted to participate in the foundation of the Unity party, Civic Union reported in a statement on its website. -

Reforming the Police in Post-Soviet States: Georgia and Kyrgystan

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. The United States Army War College The United States Army War College educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. The purpose of the United States Army War College is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers. Concurrently, it is our duty to the U.S. Army to also act as a “think factory” for commanders and civilian leaders at the strategic level worldwide and routinely engage in discourse and debate concerning the role of ground forces in achieving national security objectives. The Strategic Studies Institute publishes national security and strategic research and analysis to influence policy debate and bridge the gap between military and academia. The Center for Strategic Leadership and Development CENTER for contributes to the education of world class senior STRATEGIC LEADERSHIP and DEVELOPMENT leaders, develops expert knowledge, and provides U.S. ARMY WAR COLLEGE solutions to strategic Army issues affecting the national security community. The Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute provides subject matter expertise, technical review, and writing expertise to agencies that develop stability operations concepts and doctrines. U.S. Army War College The Senior Leader Development and Resiliency program supports the United States Army War College’s lines of SLDR effort -

Health Systems in Transition

61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 1 03/03/2020 09:55 Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Vol. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21 No. 4 2019 Health Systems in Transition: in Transition: Health Systems C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Latvia Latvia Health system review Daiga Behmane Alina Dudele Anita Villerusa Janis Misins The Observatory is a partnership, hosted by WHO/Europe, which includes other international organizations (the European Commission, the World Bank); national and regional governments (Austria, Belgium, Finland, Kristine Klavina Ireland, Norway, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the Veneto Region of Italy); other health system organizations (the French National Union of Health Insurance Funds (UNCAM), the Dzintars Mozgis Health Foundation); and academia (the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and the Giada Scarpetti London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM)). The Observatory has a secretariat in Brussels and it has hubs in London at LSE and LSHTM) and at the Berlin University of Technology. HiTs are in-depth profiles of health systems and policies, produced using a standardized approach that allows comparison across countries. They provide facts, figures and analysis and highlight reform initiatives in progress. Print ISSN 1817-6119 Web ISSN 1817-6127 61575 Latvia HiT_2_WEB.pdf 2 03/03/2020 09:55 Giada Scarpetti (Editor), and Ewout van Ginneken (Series editor) were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European -

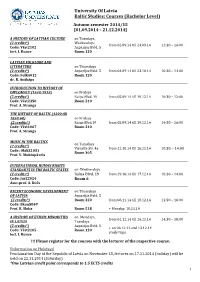

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

Kumulativna Medčasovna Datoteka CEEB 1-8

Evrobarometer Srednje in Vzhodne Evrope 1990-1997: Kumulativna medčasovna datoteka CEEB 1-8 Reif, Karlheinz ADP - IDNo: CEEB1_8 Izdajatelj: Arhiv družboslovnih podatkov URL: https://www.adp.fdv.uni-lj.si/opisi/ceeb1_8 E-pošta za kontakt: [email protected] Opis raziskave Osnovne informacije o raziskavi ADP - IDNo: CEEB1_8 Glavni avtor(ji): Reif, Karlheinz, European Comission, Brussels Ostali (strokovni) sodelavci: Cunningham, George Kuzma, Malgorzata Hersom, Louis Vantomme, Jacques Izdelava: ZA - Zentralarchiv für Empirische Sozialforschung, ZEUS - Zentrum für Europäische Umfrageanalysen und Studien (Berlin, Nemčija, Köln, Nemčija, Mannheim, Nemčija; 2004) Datum izdelave: 2004 Kraj izdelave: Berlin, Nemčija, Köln, Nemčija, Mannheim, Nemčija Uporaba računalniškega programa za izdelavo podatkov: ni podatka Finančna podpora: CEC - Komisija evropskih skupnosti - Commission of European Communities, Brusel Številka projekta: ni podatka Izdajatelj: ADP - Arhiv družboslovnih podatkov - Univerza v Ljubljani Od: Izročil: ZA - Zentralarchiv für Empirische Sozialforschung Datum: 2005-09-14 Raziskava je del serije: CEEB - Evrobarometer srednje in vzhodne Evrope Raziskava Evrobarometer v srednji in vzhodni Evropi (CEEB) se je izvajala med letoma 1990 in 1997 pod okriljem Evropske komisije. Vodila sta jo Karlheinz Reif (do 1995) in George Cunningham. Izvedena je bila osemkrat v več kot 20 državah vzhodne Evrope (seznam sodelujočih po posameznih letih http://www.gesis.org/en/data_service/eurobarometer/ceeb/countries.htm). Vsako leto jeseni so ponovno spremljali odnos ljudi v posameznih državah do ekonomskih in demokratičnih reform v njihovih državah in zavest o dogajanju v Evropski uniji. Raziskava je sorodna standardnemu Evrobarometru, ki poteka v polletnih obdobjih v državah članicah Evropske unije in se prav tako osredotoča na javno podporo EU in drugih tem, ki so tičejo Evrope nasploh. -

From Tribe to Nation a Brief History of Latvia

From Tribe to Nation A Brief History of Latvia 1 Cover photo: Popular People of Latvia are very proud of their history. It demonstration on is a history of the birth and development of the Dome Square, 1989 idea of an independent nation, and a consequent struggle to attain it, maintain it, and renew it. Above: A Zeppelin above Rīga in 1930 Albeit important, Latvian history is not entirely unique. The changes which swept through the ter- Below: Participants ritory of Latvia over the last two dozen centuries of the XXV Nationwide were tied to the ever changing map of Europe, Song and Dance and the shifting balance of power. From the Viking Celebration in 2013 conquests and German Crusades, to the recent World Wars, the territory of Latvia, strategically lo- cated on the Baltic Sea between the Scandinavian region and Russia, was very much part of these events, and shared their impact especially closely with its Baltic neighbours. What is unique and also attests to the importance of history in Latvia today, is how the growth and development of a nation, initially as a mere idea, permeated all these events through the centuries up to Latvian independence in 1918. In this brief history of Latvia you can read how Latvia grew from tribe to nation, how its history intertwined with changes throughout Europe, and how through them, or perhaps despite them, Lat- via came to be a country with such a proud and distinct national identity 2 1 3 Incredible Historical Landmarks Left: People of The Baltic Way – this was one of the most crea- Latvia united in the tive non-violent protest activities in history. -

(Translation and Terminology Centre) with Amending Laws Of: 1 Septemb

Text consolidated by Tulkošanas un terminoloģijas centrs (Translation and Terminology Centre) with amending laws of: 1 September 1992; 8 June 1994; 27 October 1994; 24 November 1994; 2 November 1995; 23 May 1996; 5 December 1996; 20 March 1997; 23 October 1997; 13 May 1999; 4 November 1999; 15 June 2000; 4 October 2001; 6 December 2001; 24 January 2002; 20 June 2002; 24 October 2002; 19 December 2002; 20 March 2003; 29 May 2003; 27 May 2004; 16 December 2004; 14 April 2005. If a whole or part of a section has been amended, the date of the amending law appears in square brackets at the end of the section. The Supreme Council of the Republic of Latvia has adopted the following Law: On Police This Law sets out the concept of the police, its tasks, principles of operation and place in the system of State administration and local government institutions, the duties, rights, structure and competence of the police and legal protection for police officers, operational guarantees, liability, basic principles for performance of service; financing and procedures for the provision of material and technical facilities; and the supervision and control of police operations. The provisions of this Law are not applicable to the activities of the State Revenue Service Financial Police. [5 December 1996] Chapter I General Provisions Section 1. The Police The police are an armed, militarised State or local government authority, whose duty is to protect from criminal and other illegal threats life, health, rights and freedoms, property, and the interests of society and the State. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

Latvia Towards Europe: Internal Security Issues

North Atlantic Treaty Organization Andris Runcis LATVIA TOWARDS EUROPE: INTERNAL SECURITY ISSUES Final Report The preparation of this Report was made possible through a NATO Award. Rîga, 1999 1 Content Introduction 3 1. The basic aspects of a country’s security 5 2. Latvia’s security concept 8 3. Corruption 10 4. Unemployment 17 5. Non-governmental organizations 19 6. The Latvian banking system and its crisis 27 7. Citizenship issue 32 Conclusion 46 Appendix 48 2 Introduction The security of small countries has been a difficult problem since ancient times. Now, when the Cold War has ended and Europe has moved from a bipolar to a multipolar system, when the communist system in Eastern Europe has collapsed and the Soviet empire has disintegrated – processes which have led to the appearance of a series of new and mostly small countries in Europe – we are witnessing a renaissance of small countries in the international arena. Since regaining independence Latvia’s general foreign policy orientation has been associated with integration into European economic, political and military structures where full membership in the European Union (EU) is the cornerstone. The issue has been one of the most consolidated and undisputed on the country’s political agenda. Latvian politicians have stressed the country’s wish to become a member state of the European Union. On October 14, 1995, all political parties represented in the Parliament supported the State President’s proposed Declaration on the Policy of Latvian Integration in the European Union. On October 27, Latvia submitted its application for membership to the EU. -

Intrazonal Agricultural Resources in Kurzeme Peninsula

ECONOMICS INTRAZONAL AGRICULTURAL RESOURCES IN KURZEME PENINSULA Linda Siliòa Latvia University of Agriculture e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The paper focuses on the exposition of the research results on agricultural resources in Kurzeme peninsula–climatic resources, qualitative evaluation of the land, condition of land amelioration, topographic resources, and structural breakdown of farm land by types of use. It is concluded that extremely various climatic and soil conditions govern in the region. The Southeast part of Kurzeme peninsula is displayed very favourably by the aggregate value of agricultural resources. Labour productivity in Kurzeme has been analysed as well. Key words: agriculture, factor, peninsula, resources. Introduction ferent and even extremely different. These aspects have Encyclopaedical publication ‘Pasaules zemes un stimulated more profound or profound complex research tautas’ (Lands and Peoples of the World, 1978) defines on each intrazone or micro-region, or sub-district of natu- Kurzeme peninsula as the Northwest part of Latvia lying ral conditions. between the Baltic Sea in the West and the Riga Gulf in the K. Brîvkalns (1959), a researcher of soil and natural East. conditions, has displayed five sub-districts or intrazones of Latvian geographers (Latvijas ìeogrâfija, 1975) char- natural conditions (soils) in Kurzeme: acterise Kurzeme peninsula and its intrazonal differences • coastal sandy lowland (1a) stretching along the from climatic (Temòikova, 1958), relief, soil, and other as- coasts of the Baltic Sea and the Riga Gulf and covers pects essential for agriculture (Brîvkalns et al., 1968). the Northern part of the region; The total length of the sea and gulf borderline is twice • Western Kurzeme plain and hill land (2a) – parts of longer than its land borderline, where it verges on Dobele Liepâja and Kuldîga districts; and Riga districts. -

Saeima Election Day on October 2 General Information and Note to Journalists

LATVIAN INSTITUTE FACTSHEET NO 40 SEPTEMBER 24, 2010 Based on information provided by the Central Election Commission. SAEIMA ELECTION DAY ON OCTOBER 2 GENERAL INFORMATION AND NOTE TO JOURNALISTS The 10 th Saeima (parliament) elections in Latvia will be held on Saturday, 2 October 2010. General Provisions The elections for the Saeima in Latvia are held every four years on the first Saturday in October. The Latvia parliamentary election is a proportional representation election system by secret ballot for the 100 seats in the Saeima. The Saeima elections are held in five constituencies: Rīga, Vidzeme, Latgale, Zemgale and Kurzeme. Four months before election day, the Central Election Commission determines the number of Saeima seats for each of the five constituencies, based on the Population Register statistics. On June 1, 2010, the total amount of voters was 1 532 851. They will send 100 deputies to the parliament - Saeima: Constituency No of voters No of elected MPs Kurzeme 205 112 13 Zemgale 232 689 15 Latgale 238 837 16 Vidzeme 406 985 27 Rīga and residents abroad 449 228 29 Total 1 532 851 100 Only those lists of candidates which have received at least 5% of the total number of votes cast in all five election constituencies will be elected to the Saeima. Suffrage Citizens of Latvia who have the right to vote and are 18 years of age or over on election day are eligible to participate in the parliamentary elections. To participate in the Saeima elections a voter needs to have a valid Latvian passport in which a stamp will be placed to mark their participation in the elections. -

Minutes Euroregion Baltic Executive Board Embassy of Sweden, Vilnius, 23 January 2002

23 January 2002 Euroregion Baltic Present Presidency Southeast Sweden 2001-2002 Minutes Euroregion Baltic Executive Board Embassy of Sweden, Vilnius, 23 January 2002 Board members: Roger Kaliff, President, Southeast Sweden Normunds Niedols, Vice President, Liepaja City Council Knud Andersen, Bornholm National secretariats: Roma Stubriene, Klaipeda County Maria Lindbom, Southeast Sweden PG Lindencrona, Southeast Sweden Gunta Strele, Liepaja City Council Gunars Ansins, Liepaja City Council Malgorzata Samusjew, ERB Poland Niels Chresten Andersen, Bornholm Interreg IIIB (PIA): Håkan Brynielsson, Chairman of Working group Rolf A Karlson, Expert Zbigniew Czepulkowski, member of Working group Other guests: Vytautas Rinkevicius, Secretary Klaipeda County Mr Arbergs, Mayor of Talsi City (presiding BSC Planning Region) Berndt Johnsson, Region Blekinge (becoming Swedish ERB Board repr) Carl Sonesson, President Region Skåne/Vice President SydSam Edvardas Borisovas, Chairman Reg Coop Unit/Ministry Foreign Aff Lith Ms J. Kriskovieciene, Counsellor Reg Coop Unit/Ministry Foreign Aff Lith Jan Palmstierna, Ambassador, Embassy of Sweden, Vilnius Carl-Michael Gräns, Secretary, Embassy of Sweden, Vilnius The Kaliningrad party is not present at the meeting. § 1 Welcome Mr Kaliff opens the meeting by welcoming everybody to the board meeting at the Embassy of Sweden in Vilnius, expressing gratitude towards the embassy for letting us use their premises two days, for the PIA working group and the board meeting. Mr Berndt Johnsson, Region Blekinge, becoming Swedish representative in the ERB Board, Mr Carl Sonesson, President Region Skåne/Vice President SydSam, Mr Arbergs, President of BSC Planning Region as well as guests from the Lithuanian Foreign Ministry are especially welcomed. § 2 Appointment of a member to co-sign the minutes of today’s meeting Mr Niedols is chosen to check and co-sign the minutes of today’s meeting.