Open Buckley Final Thesis .Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature • the Worst Movie Ever!

------------------------------------------Feature • The Worst Movie Ever! ----------------------------------------- Glenn Berggoetz: A Man With a Plan By Greg Locke with the film showing in L.A., with the name of the film up line between being so bad that something’s humorous and so on a marquee, at least a few dozen people would stop in each bad it’s just stupid. [We shot] The Worst Movie Ever! over The idea of the midnight movie dates back to the 1930s night to see the film. As it turned out, the theater never put the course of two days – a weekend. I love trying to do com- when independent roadshows would screen exploitation the title of the film up on the marquee, so passers-by were pletely bizarre, inane things in my films but have the charac- films at midnight for the sauced, the horny and the lonely. not made aware of the film screening there. As it turned out, ters act as if those things are the most natural, normal things The word-of-mouth phenomenon really began to hit its only one man happened to wander into the theater looking to in the world.” stride in the 50s when local television stations would screen see a movie at midnight who decided that a film titled The Outside of describing the weird world of Glenn Berg- low-budget genre films long after all the “normal” people Worst Movie Ever! was worth his $11. goetz, the movie in question is hard to give an impression of were tucked neatly into bed. By the 1970s theaters around “When I received the box office number on Monday, I with mere words. -

Recommended Films: a Preparation for a Level Film Studies

Preparation for A-Level Film Studies: First and foremost a knowledge of film is needed for this course, often in lessons, teachers will reference films other than the ones being studied. Ideally you should be watching films regularly, not just the big mainstream films, but also a range of films both old and new. We have put together a list of highly useful films to have watched. We recommend you begin watching some these, as and where you can. There are also a great many online lists of ‘greatest films of all time’, which are worth looking through. Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 1941 Arguably the greatest film ever made and often features at the top of film critic and film historian lists. Welles is also regarded as one the greatest filmmakers and in this film: he directed, wrote and starred. It pioneered numerous film making techniques and is oft parodied, it is one of the best. It’s a Wonderful Life: Frank Capra, 1946 One of my personal favourite films and one I watch every Christmas. It’s a Wonderful Life is another film which often appears high on lists of greatest films, it is a genuinely happy and uplifting film without being too sweet. James Stewart is one of the best actors of his generation and this is one of his strongest performances. Casablanca: Michael Curtiz, 1942 This is a masterclass in storytelling, staring Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman. It probably has some of the most memorable lines of dialogue for its time including, ‘here’s looking at you’ and ‘of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine’. -

Blockbusters Als Event Movies: Over De Lancering Van the Lord of the Rings: the Return of the King

Daniel Biltereyst Blockbusters als event movies: over de lancering van The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King Films als Titanic en The Lord of the Rings worden veelal gezien als mijlpalen in de geschiedenis van de hedendaagse blockbusterfilmcultuur. In de litera- tuur over New Hollywood en blockbusters worden dit soort films veelal aan- geduid als event movies. Aan de hand van de lancering van The Return of the King in België tracht deze bijdrage enkele cruciale dimensies in het eventkarakter van hedendaagse blockbusters te begrijpen. Inleiding Titanic (1997) van de Amerikaanse filmregisseur James Cameron wordt in de literatuur over de hedendaagse ‘filmed entertainment industry’ in vele opzichten beschouwd als een absolute mijlpaal. Titanic was niet alleen een grandioze spektakelfilm met ongeziene special effects en bijzondere produc- tiemiddelen. Camerons film brak ook alle records inzake productie-, distri- butie- en releasebudgetten en releasestrategieën. Titanic werd het school- voorbeeld van de manier waarop de Amerikaanse filmindustrie een wereldpubliek wil bereiken. De productiehuizen achter dit succesvolle megaspektakel (Paramount en 20th Century Fox) slaagden erin om de film te laten uitgroeien tot een wereldwijde hype en een publieke gebeurtenis (of event) van de eerste orde. De film staat symbool voor de manier waarop Hollywood op een geïntegreerde wijze invulling tracht te geven aan de defi- nitie van blockbusters als event movies (o.a. Elsaesser, 2001; Blanchet, 2003, pp. 255-256; Neale, 2003, p. 47; Stringer, 2003, p. 2). Binnen het onderzoek en de literatuur over hedendaagse populaire (film)cultuur groeit de interesse voor het fenomeen van de global block- busters (Stringer, 2003). -

American Independent Cinema 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AMERICAN INDEPENDENT CINEMA 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geoff King | 9780253218261 | | | | | American Independent Cinema 1st edition PDF Book About this product. Hollywood was producing these three different classes of feature films by means of three different types of producers. The Suburbs. Skip to main content. Further information: Sundance Institute. In , the same year that United Artists, bought out by MGM, ceased to exist as a venue for independent filmmakers, Sterling Van Wagenen left the film festival to help found the Sundance Institute with Robert Redford. While the kinds of films produced by Poverty Row studios only grew in popularity, they would eventually become increasingly available both from major production companies and from independent producers who no longer needed to rely on a studio's ability to package and release their work. Yannis Tzioumakis. Seeing Lynch as a fellow studio convert, George Lucas , a fan of Eraserhead and now the darling of the studios, offered Lynch the opportunity to direct his next Star Wars sequel, Return of the Jedi Rick marked it as to-read Jan 05, This change would further widen the divide between commercial and non-commercial films. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Until his so-called "retirement" as a director in he continued to produce films even after this date he would produce up to seven movies a year, matching and often exceeding the five-per-year schedule that the executives at United Artists had once thought impossible. Very few of these filmmakers ever independently financed or independently released a film of their own, or ever worked on an independently financed production during the height of the generation's influence. -

University of Namibia (Unam)

, ... .... * TODAY: WALVIS ELECTIONS ON CARDS * READERS' LETTERS * RUGBY CLASH * "'" Bringing Africa South Vol.3 No.413 N$1.50 (GST Inc.) Friday May 20 1.994 Princess Diana to the rescue Improve your chess LONDON: The Princes of Wales (left) helped skills and ~ \Vin N$100 save the life of a drown ing tramp in a dramatic rescue in London's Re THIS week The Namibian already an 'expert' -check it out gent's Park, the Daily launches a new weekly Chess too. Mail reported yesterday. competition . in the popular It could win you N$I 00. The incident happened Weekender supplement. The Don-t miss out out on the new ~ late on Sunday after Prin City Savings and Investment The Namibian/CSIB competi cess Diana had been jog Bank - "the bank we can call tion. You can also still win N$I SO ging and was being our own--- has kindly agreed to in the Spot the Word competi driven home by her .s ponsor a prize of N$I 00 each tion. chauffeur, when a tour week. Today's W eekender is back ist leapt out and shouted: Chess is a fast-growing sport to its full fo rmat with all your "Quick, there's a man in in Namibia with many young regular favourites, plus articles the water." people and schools taking it onJackson Kaujeua's new book_ Diana jumped out of up. If you haven't caught on to alternative technology, music her car and told the the latest craze check page 10 reviews, an arts round-up and of The Weekender. -

Blockbusters

BLOCKBUSTERS HIT-MAKING, RISK-TAKING, AND THE BIG BUSINESS OF ENTERTAINMENT ANITA ELBERSE HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK 14 BLOCKBUSTERS sector's most successful impresarios are leading a revolution, trans forming the business from one that is all about selling bottles— high-priced alcohol delivered to "table customers" seated at hot spots in the club—to one that is just as much about selling tickets Chapter One to heavily marketed events featuring superstar DJs. But I'll also point to other examples, from Apple and its big bets in consumer electronics, to Victoria's Secret with its angelic-superstar-studded fashion shows, and to Burberry's success in taking the trench coat digital. As these will show, many of the lessons to be learned about blockbusters not only apply across the entertainment industry— they even extend to the business world at large. BETTING ON BLOCKBUSTERS n June 2012, less than two weeks after the news of his appoint ment as chairman of Walt Disney Pictures had Hollywood in- siders buzzing, Alan Horn walked onto the Disney studio lot. The well-liked sixty-nine-year-old executive ("I try to be a nice person almost all the time, but next to Alan Horn I look like a com plete jerk," actor Steve Carell had joked during Horn's good-bye party at Warner Bros.) was excited about joining Disney, which he described as "one of the most iconic and beloved entertainment companies in the world." But he also knew he had his work cut out for him, as Disney Pictures had posted disappointing box-office results in recent years. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

9781474410571 Contemporary

CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd i 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM Traditions in American Cinema Series Editors Linda Badley and R. Barton Palmer Titles in the series include: The ‘War on Terror’ and American Film: 9/11 Frames Per Second Terence McSweeney American Postfeminist Cinema: Women, Romance and Contemporary Culture Michele Schreiber In Secrecy’s Shadow: The OSS and CIA in Hollywood Cinema 1941–1979 Simon Willmetts Indie Reframed: Women’s Filmmaking and Contemporary American Independent Cinema Linda Badley, Claire Perkins and Michele Schreiber (eds) Vampires, Race and Transnational Hollywoods Dale Hudson Who’s in the Money? The Great Depression Musicals and Hollywood’s New Deal Harvey G. Cohen Engaging Dialogue: Cinematic Verbalism in American Independent Cinema Jennifer O’Meara Cold War Film Genres Homer B. Pettey (ed.) The Style of Sleaze: The American Exploitation Film, 1959–1977 Calum Waddell The Franchise Era: Managing Media in the Digital Economy James Fleury, Bryan Hikari Hartzheim, and Stephen Mamber (eds) The Stillness of Solitude: Romanticism and Contemporary American Independent Film Michelle Devereaux The Other Hollywood Renaissance Dominic Lennard, R. Barton Palmer and Murray Pomerance (eds) Contemporary Hollywood Animation: Style, Storytelling, Culture and Ideology Since the 1990s Noel Brown www.edinburghuniversitypress.com/series/tiac 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd iiii 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION Style, Storytelling, Culture and Ideology Since the 1990s Noel Brown 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd iiiiii 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. -

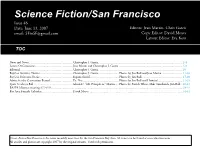

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 46 Date: June 13, 2007 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia Email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout Editor: Eva Kent

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 46 Date: June 13, 2007 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout Editor: Eva Kent TOC News and Notes .......................................................... Christopher J. Garcia ............................................................................................................... 2-4 Letters Of Comment .................................................. Jean Martin and Christopher J. Garcia ................................................................................... 5-9 Editorial ..................................................................... Christopher J. Garcia ............................................................................................................... 10 BayCon Survives, Thrives ........................................... Christopher J. Garcia ........................... Photos by Jim Bull and Jean Martin ........................... 11-16 BayCon Relocates, Rocks ........................................... España Sheriff ...................................... Photos by Jim Bull ...................................................... 17-20 Advice for the Convention Bound .............................. Dr. Noe ............................................... Photos by Jim Bull and Howeird ................................ 21-25 Space Cowboys Ball .................................................... Glenn D. “Mr. Persephone” Martin ..... Photos by Patrick White, Mike Smithwick, Jim Bull ... 26-28 BASFA Minutes: -

4.2 on the Political Economy of the Contemporary (Superhero) Blockbuster Series

4.2 On the Political Economy of the Contemporary (Superhero) Blockbuster Series BY FELIX BRINKER A decade and a half into cinema’s second century, Hollywood’s top-of-the- line products—the special effects-heavy, PG-13 (or less) rated, big-budget blockbuster movies that dominate the summer and holiday seasons— attest to the renewed centrality of serialization practices in contemporary film production. At the time of writing, all entries of 2014’s top ten of the highest-grossing films for the American domestic market are serial in one way or another: four are superhero movies (Guardians of the Galaxy, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, X-Men: Days of Future Past, The Amazing Spider-Man 2: Rise of Electro), three are entries in ongoing film series (Transformers: Age of Extinction, Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, 22 Jump Street), one is a franchise reboot (Godzilla), one a live- action “reimagining” of an animated movie (Maleficent), and one a movie spin-off of an existing entertainment franchise (The Lego Movie) (“2014 Domestic”). Sequels, prequels, adaptations, and reboots of established film series seem to enjoy an oft-lamented but indisputable popularity, if box-office grosses are any indication.[1] While original content has not disappeared from theaters, the major studios’ release rosters are Felix Brinker nowadays built around a handful of increasingly expensive, immensely profitable “tentpole” movies that repeat and vary the elements of a preceding source text in order to tell them again, but differently (Balio 25-33; Eco, “Innovation” 167; Kelleter, “Einführung” 27). Furthermore, as part of transmedial entertainment franchises that expand beyond cinema, the films listed above are indicative of contemporary cinema’s repositioning vis-à-vis other media, and they function in conjunction with a variety of related serial texts from other medial contexts rather than on their own—by connecting to superhero comic books, live-action and animated television programming, or digital games, for example. -

American Blockbuster Movies, Technology, and Wonder

MOVIES, TECHNOLOGY, AND WONDER MOVIES, TECHNOLOGY, charles r. acland AMERICAN BLOCKBUSTER SIGN, STORAGE, TRANSMISSION A series edited by Jonathan Sterne and Lisa Gitelman AMERICAN BLOCKBUSTER MOVIES, TECHNOLOGY, AND WONDER charles r. acland duke university press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 duke university press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Whitman and Helvetica lt Standard by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Acland, Charles R., [date] author. Title: American blockbuster : movies, technology, and wonder / Charles R. Acland. Other titles: Sign, storage, transmission. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Series: Sign, storage, transmission | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2019054728 (print) lccn 2019054729 (ebook) isbn 9781478008576 (hardcover) isbn 9781478009504 (paperback) isbn 9781478012160 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Cameron, James, 1954– | Blockbusters (Motion pictures)— United States—History and criticism. | Motion picture industry—United States— History—20th century. | Mass media and culture—United States. Classification:lcc pn1995.9.b598 a25 2020 (print) | lcc pn1995.9.b598 (ebook) | ddc 384/.80973—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054728 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054729 Cover art: Photo by Rattanachai Singtrangarn / Alamy Stock Photo. FOR AVA, STELLA, AND HAIDEE A technological rationale is the rationale of domination itself. It is the coercive nature of society alienated from itself. Automobiles, bombs, and movies keep the whole thing together. — MAX HORKHEIMER AND THEODOR ADORNO, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 1944/1947 The bud get is the aesthetic. — JAMES SCHAMUS, 1991 (contents) Acknowl edgments ........................................................... -

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia Email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent TOC News and Notes ...........................................Christopher J. Garcia ....................................................................................................3 Letters of Comment .....................................Jean Martin and Chris Garcia ....................................................................................4-6 Editorial .......................................................Jean Martin ................................................................................................................... 7 Ghosts and Surreal Art in Portland ...............Jean Marin ................................Photos Jean Martin ................................................8-11 Nemo Gould Sculptures ...............................Espana Sheriff ...........................Photos from www.nemomatic.com ......................12-13 Reading at Intersection for the Arts ..............Christopher J. Garcia ............................................................................................14-15 Klingon Celebration .....................................Jean Marin ................................Photos by Jean Martin .........................................16-21 BASFA Minutes ..........................................................................................................................................................................22-24