Anniversaries of the Jews in America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

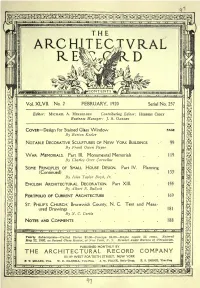

February 1920

ii^^ir^?!'**i r*sjv^c ^5^! J^^M?^J' 'ir ^M/*^j?r' ?'ij?^'''*vv'' *'"'**'''' '!'<' v!' '*' *w> r ''iw*i'' g;:g5:&s^ ' >i XA. -*" **' r7 i* " ^ , n it A*.., XE ETT XX " " tr ft ff. j 3ty -yj ri; ^JMilMMIIIIilllilllllMliii^llllll'rimECIIIimilffl^ ra THE lot ARC HIT EC FLE is iiiiiBiicraiiiEyiiKii! Vol. XLVII. No. 2 FEBRUARY, 1920 Serial No. 257 Editor: MICHAEL A. MIKKELSEN Contributing Editor: HERBERT CROLY Business Manager: ]. A. OAKLEY COVER Design for Stained Glass Window FAGS By Burton Keeler ' NOTABLE DECORATIVE SCULPTURES OF NEW YOKK BUILDINGS _/*' 99 .fiy Frank Owen Payne WAK MEMORIALS. Part III. Monumental Memorials . 119 By Charles Over Cornelius SOME PRINCIPLES OF SMALL HOUSE DESIGN. Part IV. Planning (Continued) .... .133 By John Taylor Boyd, Jr. ENGLISH ARCHITECTURAL DECORATION. Part XIII. 155 By Albert E. Bullock PORTFOLIO OF CURRENT ARCHITECTURE . .169 ST. PHILIP'S CHURCH, Brunswick County, N. C. Text and Meas^ ured Drawings . .181 By N. C. Curtis NOTES AND COMMENTS . .188 Yearly Subscription United States $3.00 Foreign $4.00 Single copies 35 cents. Entered May 22, 1902, as Second Class Matter, at New York, N. Y. Member Audit Bureau of Circulation. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ARCHITECTURAL RECORD COMPANY 115-119 FOFvIlt I i I IStt I, NEWINCW YORKTUKN WEST FORTIETHM STREET, H v>^ E. S. M tlli . T. MILLER, Pres. W. D. HADSELL, Vice-Pres. J. W. FRANK, Sec'y-Treas. DODGE. Vice-Pre* ' "ri ti i~f n : ..YY '...:.. ri ..rr.. m. JT i:c..."fl ; TY tn _.puc_. ,;? ,v^ Trrr.^yjL...^ff. S**^ f rf < ; ?SIV5?'Mr ^7"jC^ te :';T:ii!5ft^'^"*TiS t ; J%WlSjl^*o'*<JWii*^'J"-i!*^-^^**-*''*''^^ *,iiMi.^i;*'*iA4> i.*-Mt^*i; \**2*?STO I ASTOR DOORS OF TRINITY CHURCH. -

Rare Books, Autographs & Maps

RARE BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHS & MAPS Wednesday, April 17, 2019 NEW YORK RARE BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHS & MAPS AUCTION Wednesday, April 17, 2019 at 10am EXHIBITION Saturday, April 13, 10am – 5pm Sunday, April 14, Noon – 5pm Monday, April 15, 10am – 7pm Tuesday, April 16, 10am – 4pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF Printed & Manuscript Americana 1 - 50 Marian Clark Adolphson, CT Maps 51 - 57 Frances “Peggy” Brooks Autographs 58 - 70 Elizabeth and Donald Ebel Manuscripts 71 - 74 Elizabeth H. Fuller Early Printed Books 75 - 97 Robin Gottlieb Fine Bindings 98 - 107 Arnold ‘Jake’ Johnson Automobilia 108 - 112 George Labalme, Jr. Color Plate & Plate Books Including 113 - 142 Peter Mayer Science & Natural History Suzanne Schrag Travel & Sport 143 - 177 Barbara Wainscott Children’s Literature 178 - 192 Illustration Art 193 - 201 20th Century Illustrated Books 202 - 225 19th Century Illustrated Books 226 - 267 INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM Modern Literature 268 - 351 A Gentleman A Palm Beach Collector Glossary I A Maine Collector Conditions of Sale II The Collection of Rudolf Serkin Terms of Guarantee IV Information on Sales & Use Tax V Buying at Doyle VI Selling at Doyle VIII Auction Schedule IX Company Directory XI Absentee Bid Form XII Lot 167 Printed & Manuscript Americana 1 4 AMERICAN FLAG A large 35 star American Flag. Cotton or linen flag, the canton [CALIFORNIA - BANKING] with 35 stars, likely Civil War era, approximately 68 x 136 inches or Early and rare ledger of the Exchange Bank of Elsinore. 5 1/2 x 11 feet (172 x 345 cm); the canton 36 x 51 inches (91 x 129 cm), August 1889-November 1890. -

Designs in Glass •

Steuben Glass, Inc. DESIGNS IN GLASS BY TWENTY-SEVEN CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS • • STEUBEN TH E CO LLE CT IO N OF DE S IG NS I N GLASS BY TWE N TY- SEVEN CONTE iPORARY ARTISTS • STEUBE l G L ASS lN c . NEW YORK C ITY C OP YTIT G l-IT B Y ST EUBEN G L ASS I NC . J ANUA H Y 1 9 40 c 0 N T E N T s Foreword . A:\1 A. L EWISOH Preface FRA K JEWETT l\lATHER, JR. Nalure of lhe Colleclion . J oH 1\1. GATES Number THOMAS BENTON 1 CHRISTIA BERARD . 2 MUIRHEAD BO E 3 JEA COCTEAU 4 JOH STEUART CURRY 5 SALVADOR DALI . 6 GIORGIO DE CHIRICO 7 A DRE DEHAI s RAO L DUFY 9 ELUC GILL 1 0 DU TCA T GRANT . 11 JOTI GREGORY 12 JEA HUGO 13 PETER HURD 14 MOISE KISLI. G 15 LEON KROLL . 16 MARIE LA RE TCIN 17 FERNAND LEGER. IS AlUSTIDE MAILLOL 19 PAUL MANSHIP 20 TT E TRI MATISSE 21 I AM OGUCHI. 22 GEORGIA O'KEEFFE 23 JOSE MARIA SERT . 24 PAVEL TClfELlTCHEW. 25 SID EY WAUGII 26 GHA T WOOD 27 THE EDITION OF THESE PIECE IS Lil\1ITED • STEUBEN WILL MAKE SIX PIECES FROM EACH OF THESE TWENTY SEVE DESIGNS OF WHICH ONE WILL BE RETAINED BY STEUBEN FOR ITS PERMANE T COLLECTIO TIIE REMAI I G FIVE ARE THUS AVAILABLE FOR SALE F 0 R E w 0 R D SAM: A. LEWISOHN This is a most important enterprise. To connecl lhe creative artist with every-day living is a difficult task. -

The Jewel City

The Jewel City Ben Macomber The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Jewel City, by Ben Macomber Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Jewel City Author: Ben Macomber Release Date: January, 2005 [EBook #7348] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on April 18, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE JEWEL CITY *** Produced by David Schwan Panama-Pacific International Exposition Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. The Jewel City: Its Planning and Achievement; Its Architecture, Sculpture, Symbolism, and Music; Its Gardens, Palaces, and Exhibits By Ben Macomber With Colored Frontispiece and more than Seventy-Five Other Illustrations Introduction No more accurate account of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition has been given than one that was forced from the lips of a charming Eastern woman of culture. -

The Art of the Exposition

The Art of the Exposition Eugen Neuhaus The Art of the Exposition Table of Contents The Art of the Exposition.........................................................................................................................................1 Eugen Neuhaus..............................................................................................................................................1 Publisher's Announcement.............................................................................................................................1 The Architecture............................................................................................................................................1 The Sculpture.................................................................................................................................................9 The Color Scheme Landscape Gardening....................................................................................................17 Mural Decorations........................................................................................................................................20 The Illumination. Conclusion......................................................................................................................24 Appendix......................................................................................................................................................26 i The Art of the Exposition Eugen Neuhaus This page copyright © 2002 Blackmask Online. -

Official Guide of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, 1915 : San

OtpicialGuipe PANAAA - PACIFIC I NTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION SAN FRANCISCO 19IS W, A Cordial Welcome Awaits You at the Westinghouse Electric Exhibits in The Palace of Transportation The Palace of Machinery The Mine—Palace of Mines and Metallurgy □ □□ Westinghouse Electric products are to be found throughout the Exposition Grounds in the Exhibit Palaces, Nation Buildings, State Buildings, and the “Zone.” Westinghouse Electric achievements have made large Expositions possible. Its devices generate electric energy; transmit this energy long distances to you; haul trains; operate the street cars in which you ride; light your city; convey minerals from vein to surface; drive ma¬ chinery in every kind of factory; bring assistance and comfort to your home; start and light your motor ^ar; drive your electric pleasure vehicle- and do a multitude of other things. Such devices can be seen in these exhibits. See them, and when you buy- Specify Westinghouse Electric Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co. East Pittsburg, Pa. U. S. A. Sales Offices in 45 American Cities Tin c* TtnciH/^ Ttntn the only hotel with. X ilU lllOlUC XI 111 IN THE GROUNDS OF THE Panama-Pacific International Exposition QPENI NG January 15, 1915. Absolute fire protection. Individual rates $1.00 to $5j00 per day, European plan. American plan rates added. Restaurants and Cafes. All outside rooms have private baths. Telephone in each room. Steam heated throughout. Convention and Banquet Halls for large gatherings._ Under the Supervision of the Exposition Management Exposition B'dg. TheWdlrnn4" Make Your Reservations NOW San Francisco “BOSSY BRAND” MILK In Bottles—Not Canned. Noted for Its Rich, Pure Flavor. -

Isidore Konti Papers

Isidore Konti papers Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Isidore Konti papers AAA.kontisid Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Isidore Konti -

The Public Sculpture of John De La Mothe Gutzon Borglum in Newark, New Jersey, 1911 - 1926

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (June 1991) United States Department of the Interior APR 2 0 1994 SEP 2 7 1994 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places - Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Public Sculpture in Newark, New Jersey B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Public Sculpture of John de la Mothe Gutzon Borglum in Newark, New Jersey, 1911 - 1926 C. Form Preparedj name/title Ulana D. Zakalak/ Historic Preservation Consultant organization Zakalak Associates date April 13, 1994 street & number 57 Cayuga Avenue telephone (908) 571-3176 city or town Oceanport state New Jersey zip code Q7757________ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines fpr Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

A Guide to the John Quincy Adams Ward Papers Summary Information

A Guide to the John Quincy Adams Ward Papers Summary Information Repository Albany Institute of History & Art Library Creator John Quincy Adams Ward Title John Quincy Adams Ward Papers, 1800-1933 Identifier CM 544 Date 1800-1933 Physical Description 2.08 linear feet; 5 Hollinger boxes Physical Location The materials are located onsite in the Museum. Language of the Material English Abstract John Quincy Adams Ward was born on June 29, 1830, in Urbana, Ohio. The fourth of eight children born to John Anderson (1783-1855) and Eleanor Macbeth Ward (1795- 1856), one of his younger brothers was the artist, Edgar Melville Ward (1839-1915). Encouraged in his early art by local potter, Miles Chatfield, Ward became discouraged after attending a sculpture exhibition in Cincinnati in 1847. While living with his older sister Eliza (1824-1904) and her husband in Brooklyn, New York, Ward began training under sculptor Henry Kirke Brown (1814-1886), under whose tutelage he would remain from 1849-1856. In 1857 he set out on his own, making busts of men in public life. In 1861, Ward set up his own studio in New York City, where he dedicated himself to developing an American school of sculpture. Left a widower twice, Ward eventually married Rachel Smith (1849-1933) in 1906. She was instrumental in helping to get his work and papers placed in numerous institutions. During his lifetime, Ward created numerous public sculptures, including one of General Phillip Sheridan in Albany, New York, and he participated in and served on numerous boards. Ward died in New York City in 1910, and was buried in Oakdale Cemetery in Urbana, Ohio. -

Historical Plaques

Contents Title Page Contents The 99% Invisible Field Guide to the Cover Dedication Copyright Introduction Chapter 1: Inconspicuous Ubiquitous Camouflage Accretions Chapter 2: Conspicuous Identity Safety Signage Chapter 3: Infrastructure Civic Water Technology Roadways Public Chapter 4: Architecture Liminal Materials Regulations Towers Foundations Heritage Chapter 5: Geography Delineations Configurations Designations Landscapes Synanthropes Chapter 6: Urbanism Hostilities Interventions Catalysts Outro Acknowledgments Bibliography Index About the Authors Connect with HMH The 99% Invisible Field Guide to the Cover Fig. 1 • EMERGENCY BOXES: Small safes affixed to urban architecture allow emergency personnel to quickly access buildings using a master key, saving time and lives in critical situations. Instead of breaking glass and risking injury or causing damage, firefighters can walk right in. Advanced versions of these boxes also allow responders to control gas and sprinkler systems. Fig. 2 • ANCHOR PLATES: Small metal circles, squares, and stars affixed to building exteriors are visible parts of wall anchoring systems designed to hold old buildings together and to prevent bricks from falling off of facades. Fig. 3 • THOMASSONS: As cities change, sometimes useless remnants are left behind. Some of these artifacts are eventually demolished, but others persist, and some are even actively cleaned and repaired despite no longer serving their original purpose. A Japanese artist dubbed them “Thomassons,” referencing a baseball player whose career took a turn, leaving him well paid but mostly on the bench—useless, but maintained. Fig. 4 • TRAFFIC LIGHTS: Most of the world’s traffic signals are arranged with the red light on top, yellow or amber in the middle, and green at the bottom. -

A Finding Aid to the Photographs of Karl Francis Theodore Bitter and Gustave Gerlach, Circa 1892-Circa 1915, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Photographs of Karl Francis Theodore Bitter and Gustave Gerlach, circa 1892-circa 1915, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie Ashley Funding for the processing and digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. 2019/07/17 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Papers, circa 1892-circa 1915.................................................................. 4 Series 2: Photographs, circa 1895-circa 1915........................................................ -

Gainsborough Studios and the Proposed Designation of the Related I.Andmark Site (Item No

I.andmarks Presei:vation Commission February 16, 1988; Designation List 200 LP-1423 GAINSOOROUGH S'IUDIOS, 222 Central Park South, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1907-08, architect Cbarles w. Buckham. I.andmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1030, lot 46. on April 12, 1983, the Landmarks Preservation Connnission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Gainsborough studios and the proposed designation of the related I.andmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to June 14, 1983 (Item No. 1). The hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. 'IWo witnesses spoke in favor of designation. One witness spoke in opposition to designation. The Connnission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS summary The Gainsborough Studios is a rare surviving example of artists' cooperative housing, a building type popular in Manhattan for a brief period in the early twentieth century. Built during the heyday of its type, in 1907-08, the Gainsborough provided both living and working spaces. The handsome, distinctive design of the building reflects its unusual purpose. Large, double-height windows provide an abundance of northern light to the artists' studios. Designed , managed and inhabited by artists, the building was given artistic connotations via its name and the proliferation of exterior ornament. The latter includes a bust of the artist Thomas Gainsborough in an ornate setting, multi-colored tile embedded in the brick facade, and an impressive frieze entitled "A Festival Procession of the Arts" by the s~ccessful sculptor Isidore Konti.