Gainsborough Studios and the Proposed Designation of the Related I.Andmark Site (Item No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

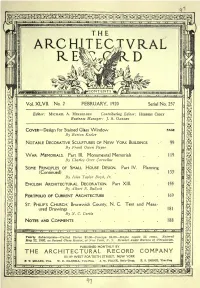

February 1920

ii^^ir^?!'**i r*sjv^c ^5^! J^^M?^J' 'ir ^M/*^j?r' ?'ij?^'''*vv'' *'"'**'''' '!'<' v!' '*' *w> r ''iw*i'' g;:g5:&s^ ' >i XA. -*" **' r7 i* " ^ , n it A*.., XE ETT XX " " tr ft ff. j 3ty -yj ri; ^JMilMMIIIIilllilllllMliii^llllll'rimECIIIimilffl^ ra THE lot ARC HIT EC FLE is iiiiiBiicraiiiEyiiKii! Vol. XLVII. No. 2 FEBRUARY, 1920 Serial No. 257 Editor: MICHAEL A. MIKKELSEN Contributing Editor: HERBERT CROLY Business Manager: ]. A. OAKLEY COVER Design for Stained Glass Window FAGS By Burton Keeler ' NOTABLE DECORATIVE SCULPTURES OF NEW YOKK BUILDINGS _/*' 99 .fiy Frank Owen Payne WAK MEMORIALS. Part III. Monumental Memorials . 119 By Charles Over Cornelius SOME PRINCIPLES OF SMALL HOUSE DESIGN. Part IV. Planning (Continued) .... .133 By John Taylor Boyd, Jr. ENGLISH ARCHITECTURAL DECORATION. Part XIII. 155 By Albert E. Bullock PORTFOLIO OF CURRENT ARCHITECTURE . .169 ST. PHILIP'S CHURCH, Brunswick County, N. C. Text and Meas^ ured Drawings . .181 By N. C. Curtis NOTES AND COMMENTS . .188 Yearly Subscription United States $3.00 Foreign $4.00 Single copies 35 cents. Entered May 22, 1902, as Second Class Matter, at New York, N. Y. Member Audit Bureau of Circulation. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ARCHITECTURAL RECORD COMPANY 115-119 FOFvIlt I i I IStt I, NEWINCW YORKTUKN WEST FORTIETHM STREET, H v>^ E. S. M tlli . T. MILLER, Pres. W. D. HADSELL, Vice-Pres. J. W. FRANK, Sec'y-Treas. DODGE. Vice-Pre* ' "ri ti i~f n : ..YY '...:.. ri ..rr.. m. JT i:c..."fl ; TY tn _.puc_. ,;? ,v^ Trrr.^yjL...^ff. S**^ f rf < ; ?SIV5?'Mr ^7"jC^ te :';T:ii!5ft^'^"*TiS t ; J%WlSjl^*o'*<JWii*^'J"-i!*^-^^**-*''*''^^ *,iiMi.^i;*'*iA4> i.*-Mt^*i; \**2*?STO I ASTOR DOORS OF TRINITY CHURCH. -

RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (Aka 461-465 Park Avenue, and 101East5t11 Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 29, 2002, Designation List 340 LP-2118 RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (aka 461-465 Park Avenue, and 101East5T11 Street), Manhattan. Built 1925-27; Emery Roth, architect, with Thomas Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1312, Lot 70. On July 16, 2002 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Ritz Tower, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.2). The hearing had been advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Ross Moscowitz, representing the owners of the cooperative spoke in opposition to designation. At the time of designation, he took no position. Mark Levine, from the Jamestown Group, representing the owners of the commercial space, took no position on designation at the public hearing. Bill Higgins represented these owners at the time of designation and spoke in favor. Three witnesses testified in favor of designation, including representatives of State Senator Liz Kruger, the Landmarks Conservancy and the Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission has received letters in support of designation from Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, from Community Board Five, and from architectural hi storian, John Kriskiewicz. There was also one letter from a building resident opposed to designation. Summary The Ritz Tower Apartment Hotel was constructed in 1925 at the premier crossroads of New York's Upper East Side, the comer of 57t11 Street and Park A venue, where the exclusive shops and artistic enterprises of 57t11 Street met apartment buildings of ever-increasing height and luxury on Park Avenue. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

MARITIMER February 2008 the NEW YORK Issue Insider’S Guide to DOCKSIDE New York DINING

The Metro Group MARITIMER FEBRUARY 2008 the NEW YORK issue INsIdER’s guIdE to dOCKsIdE NEW york DINING REMEMBERINg the WHITEHALL CLuB Blurring FRONT office BACK office lines MARITIME ART in PuBLIC PLACEs MARITIMER February 2008 WELCOME photo by Tania Savayan photo by Tania GR OUP MA O R R I T T I M E E METRO GROUP MARITIME 61 BROADWAY New YoRK, NY M www.mgmUS.com (212) 425-7774 The Metro Group FEBRUARY 2008 MARITIMER N E W Y O R K I ss UE The Metro Group MARITIMER 6 THE WHITEHALL CLUB Vol. 2 No. 8 PORTSIDE RESTAURANTS PUBLISHER Marcus L. Arky LUNAR NEW YEAR PREVIEW ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER 11 CARPE Victoria Medeiros Q&A WITH NEW YORK ARTIST TERRENCE MALEY EDITOR IN CHIEF 12 Alia Mansoori RESEARCH EDITOR 14 BLURRING THE LINES BETWEEN FRONT OFFICE AND BACK OFFICE Kemal Kurtulus COPY EDITOR INSider’S GUIDE TO NYC Emily Ballengee 16 ART DIRECTOR PER Courtnay Loch NO OFFSET RULE 19 CONTRIBUTORS Michael Arky 20 MARITIME ART IN PUBLIC PLACES Kate Ballengee Benjamin Kinberg Filip Kwiatkowski NEW MGM CUSTOMIZABLE INTERFACE Tania Savayan 22 DIEM 23 BOOK REVIEW: PETE HAMILL’S NORTH RIVER 6 Broadway Suite 40 16 New York, NY 0006 GR OUP MA O R phone (22) 425-7774 R I T fax (22) 425-803 8 T I M E [email protected] E Please visit www.mgmus.com 12 M Printed in the U.S.A. Copyright © 2008 Metro Group Maritime Publishing to make way for luxury condominiums. The items will be displayed in the 2th Floor corridor of 7 Battery Place where both men still work. -

Thomas J. Walsh Art Gallery Exhibitions, 1990-2013 List

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield The Walsh Gallery Exhibition History 1990-2013 Walsh Gallery Exhibition History 1990-2013 2020 Thomas J. Walsh Art Gallery Exhibitions, 1990-2013 List Fairfield University Art Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/walshgallery- exhibitions-1990-2013 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas J. Walsh Art Gallery Exhibitions, 1990-2013 2013 Winter: Colleen Browning: Brush with Magic (January 24 – March 24) Spring: Po Kim: Spirit of Change (April 18 – June 5) Fall: The Rise of a Landmark: Lewis Hine and the Empire State Building (September 5 – December 12) 2012 Winter: Sylvia Wald: Seven Decades (January 19 – March 18) Spring: SoloCollective - Jr/Sr Exhibition (April 12 – May 19) Summer: History of Woman (May 30 – June 23) Fall: Marlene Siff: Elements of Peace (September 20- December 9) 2011 Winter: Norman Gorbaty: To Honor My People (January 27 – March 28) Spring: The Flowering of Punk Rock (April 14 – May 27) Summer: Director's Choice: Five Local Artists (June 19 – July 16) Fall: Beyond the Rolling Fire: Paintings of Robyn W. -

Ewen Estate Auction

THE NiSW YORK HERATP. Ti3URSDAY, OCTOBER 2CK 1921. 21 ' nurses juimori and Bather Hughes, Nhw bort G. Gates, to Division 13; Llsut. Leon 8. AT AUCTION. APARTMENTS. APARTMENTS. J. WATSON WEBB WILL Yciic; Piedmont, Norfolk, lowing bargee N'oa Flske, to U. S. 8. Tattnall; Lieut. Earle W. REAL ESTATE AT AUCTIOH. REAI ESTATE 18 (from Beverly), M md 24; Paoli, towing Mills, to U. 8. 8. Hocan; Lieut. John N. WOMAN BIDDERS BUILD NEAR WESTBURY barge Haverlord, Hock(anil..Wind dW, 23 Whelan. to U. 8. 8. Delong; Lieut. WllUain uillti; rain; rough aea. M. Ktlfcl. to U. 8. 8. Farcival, Lieutenant to Lieut. || BALTIMORE. Md, Oct 19-Arr(ved. stra Commander Arthur Moore, home; ni mum it cm- Whitton Farm Ban Oregorto (Br), Tuxpain; Vlatula (Danri, Maurice B. Durgln, relieved all active duty. Central Union Trust Company in i vuvu ni unuu Bey9 for Now Port Lubos; Grecian. Boston and Norfolk (community 1Life at its Best Home flatter 18th. and aailed on return). Site; Other Dealt. Cleared 19th, atru Tuacatooaa City, f»00,000 FOR SHIP CAMPAIGN. of New York, 1rrustee of the and Kobe: Phallron (Greek), YokohamaPort Maria; Bow den (Nor), Port Antonio; Washington, Oct 19..An extensive is enjoyed by every Make Part of Crowd J. Watson Webb, the polo player who (Dana), Port I^oboa. Vlatulaadvertising campaign in behalf of Estate of HENRY HILTON, Dec'd f Up Large la to aell his House" Jn Sailed ltttli, atra Lake Chelan, Near York: American lines operating "Woodbury Pawnee, do. passenger one L. at auction next Shipping Board vessels was approved Has Ordcied the of the 600 Ameri- In Auction ltoom at Ewen Syoaset, I., Saturday) BRUNSWICK. -

130 West 57Th Street Studio Building, 130 West 57Th Street, (Aka 126-132 West 57Th Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 19, 1999, Designation List 310 LP-2042 130 West 57th Street Studio Building, 130 West 57th Street, (aka 126-132 West 57th Street), Manhattan. Built, 1907-08, Pollard & Steinam, architects. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1009, Lot 46. On July 13, 1999, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the 130 West 57th Street Studio Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. There were six speakers in support of designation, including the owner of the building, representatives of the Landmarks Conservancy, the Society for the Architecture of the City, and the Historic Districts Council. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. In addition, the Commission has received letters from Assemblyman Richard N. Gottfried and from Community Board 5 in support of designation. Summary Built in 1907-08 to provide living and working facilities for artists, the studio building at 130 West 57th Street is a rare surviving example of this unusual building type, and a reminder of the early twentieth century period when West 57th Street was a center of artistic activities. Designed by architects Pollard & Steinam, who had previously created several artists' studio cooperatives on West 67th Street, this building profited from the experience of the developers and builders who had worked on the earlier structures. The artists' studio building type was developed early in the twentieth century, and was an important step toward the acceptance of apartment living for wealthy New Yorkers. -

Max Ginsburg at the Salmagundi Club by RAYMOND J

Raleigh on Film; Bethune on Theatre; Behrens on Music; Seckel on the Cultural Scene; Critique: Max Ginsburg; Lille on René Blum; Wersal ‘Speaks Out’ on Art; Trevens on Dance Styles; New Art Books; Short Fiction & Poetry; Extensive Calendar of Events…and more! ART TIMES Vol. 28 No. 2 September/October 2011 Max Ginsburg at The Salmagundi Club By RAYMOND J. STEINER vening ‘social comment’ — “Caretak- JUST WHEN I begin to despair about ers”, for example, or “Theresa Study” the waning quality of American art, — mostly he chooses to depict them in along comes The Salmagundi Club extremities — “War Pieta”, “The Beg- to raise me out of my doldrums and gar”, “Blind Beggar”. His images have lighten my spirits with a spectacular an almost blinding clarity, a “there- retrospective showing of Max Gins- ness” that fairly overwhelms the burg’s paintings*. Sixty-plus works viewer. Whether it be a single visage — early as well as late, illustrations or a throng of humanity captured en as well as paintings — comprise the masse, Ginsburg penetrates into the show and one would be hard-pressed very essence of his subject matter — to find a single work unworthy of what the Germans refer to as the ding Ginsburg’s masterful skill at classical an sich, the very ur-ground of a thing representation. To be sure, the Sal- — to turn it “inside-out”, so to speak, magundi has a long history of exhib- so that there can be no mistaking his iting world-class art, but Ginsburg’s vision or intent. It is to a Ginsburg work is something a bit special. -

220 Central Park South Garage Environmental

220 Central Park South Garage Environmental Assessment Statement ULURP #: 170249ZSM, N170250ZCM CEQR #: 16DCP034M Prepared For: NYC Department of City Planning Prepared on Behalf of: VNO 225 West 58th Street LLC Prepared by: Philip Habib & Associates June 16, 2017 220 CENTRAL PARK SOUTH GARAGE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS EAS Form……................................................................................................Form Attachment A......................................................................Project Description Attachment B..............................................Supplemental Screening Analyses Appendix I..................................................Residential Growth Parking Study Appendix II.................................................LPC Environmental Review Letter EAS Form EAS FULL FORM PAGE 1 City Environmental Quality Review ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT (EAS) FULL FORM Please fill out and submit to the appropriate agency (see instructions) Part I: GENERAL INFORMATION PROJECT NAME 220 Central Park South Parking Garage EAS 1. Reference Numbers CEQR REFERENCE NUMBER (to be assigned by lead agency) BSA REFERENCE NUMBER (if applicable) 16DCP034M ULURP REFERENCE NUMBER (if applicable) OTHER REFERENCE NUMBER(S) (if applicable) 170249ZSM, N170250ZCM (e.g., legislative intro, CAPA) 2a. Lead Agency Information 2b. Applicant Information NAME OF LEAD AGENCY NAME OF APPLICANT New York City Department of City Planning VNO 225 West 58th Street LLC NAME OF LEAD AGENCY CONTACT PERSON -

Awards and Honors

AWARDS /HONORS/PLEIN AIR INVITATIONALS/ NATIONAL EXHIBITIONS/ SOLO EXHIBITONS AWARDS • HONORS • PLEIN AIR INVITATIONALS NATIONAL EXHIBITIONS • SOLO EXHIBITONS 2015 Paradise Paintout Islamorado, FL En Plein Air Invitational January 11- 16, 2015 The Florida Four Group Exhibition The Englishman Gallery Group Exhibition, March 2015 to April 2015 Wekiva Island Paint Out Plein Air Invitational March 1- 7, 2015, Longwood, Florida Lighthouse Museum Plein Air Invitational Juror of Awards March 14, 2015 132nd Annual Member’s Exhibition Salmagundi Club 47 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York March 26, 2015 to April 30, 2015 Winter Park Paint Out Plein Air Invitational April 20 - 25,2015 Albin Polasek Museum and Sculpture Gardens, Winter Park, Florida Oil Painters of America Guest Artist Painting Demonstration National Convention in St. Augustine, FL May 1,2015 America’s Great Paint-Out 9th Annual Florida’s Forgotten Coast Plein Air Invitational, Quick Draw – First Place May 1 to 11, 2015, Port St. Joe, FL Cashiers Joy Garden Tour Artist Invitational July 16 - 19,2015 Salmagundi Club Exhibition at the Bennington Art Center Invitational May 30 – July 26,2015 1 Ambleside Gallery Solo Exhibition June & July 2015 Greensboro, NC The Florida Four Group Exhibition, Art House Casselberry, FL, November 1, 2015 to November 7, 2015 2014 The Florida Four Exhibition The Englishman Gallery February 2014 to April 2014 131st Annual Member’s Exhibition Salmagundi Club The Camphor Tree Wekiva Island Paint Out Plein Air Invitational March 2014 Longwood, Florida The Florida -

Download 1 File

N 558 A515 1922 NMAA THE DALLAS ART ASSOCIATION OFFICIAL CATALOGUE OF THE PERMANENT COLLECTION IN THE ART GALLERY AT FAIR PARK DALLAS TEXAS OPEN DAILY FREE TO THE PUBLIC from2to5p. M. 1922 / k5I5 THE DALLAS ART ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1902 CATALOGUE OF THE PERMANENT COLLECTION FAIR PARK DALLAS PRICE TWENTY-FIVE CENTS 1922 THE DALLAS ART ASSOCIATION MAKES GRATEFUL ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO THE DALLAS TIMES HERALD FOR THEIR GENEROUS PUBLIC-SPIRITED GIFT OF THIS OFFICIAL CATALOGUE OF THE PERMANENT COLLECTION IN THE ART GALLERY AT FAIR PARK, DALLAS, TEXAS. THIRD EDITION COPYRIGHT BY THE DALLAS ART ASSOCIATION 1922 "GOD IS THE SOURCE OF ART, AND ARTISTS ARE THOSE WHOM HE SELECTS TO MANIFEST SOMEWHAT OF HIS ETERNAL BEAUTY." INTRODUCTION iA Brief History of The 'Dallas <^Art ^Association and the Public zArt (gallery This art collection belongs to the City of Dallas, and it is with pride, justified by the achievement, that this account of how it came to be is here presented. The organization of the Dallas Art Association had its incep- tion in the minds of the art committee of the Public Library. In planning the library building Frank Beaugh, a well-known Texas artist, suggested that a room he properly lighted and arranged for an art gallery. This room when completed was most gratifying and attractive. A member of the building committee, the late Mr. J. S. Arm- strong, became so interested in procuring pictures that he offered to give one-half of any amount that could be raised for the purpose within a year. In 1902, following the close of the State Fair, Mrs. -

Landmarks Commission Report

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 29, 2002, Designation List 340 LP-2118 RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (aka 461- 465 Park Avenue, and 101 East 57th Street), Manhattan. Built 1925-27; Emery Roth, architect, with Thomas Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1312, Lot 70. On July 16, 2002 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Ritz Tower, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.2). The hearing had been advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Ross Moscowitz, representing the owners of the cooperative spoke in opposition to designation. At the time of designation, he took no position. Mark Levine, from the Jamestown Group, representing the owners of the commercial space, took no position on designation at the public hearing. Bill Higgins represented these owners at the time of designation and spoke in favor. Three witnesses testified in favor of designation, including representatives of State Senator Liz Kruger, the Landmarks Conservancy and the Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission has received letters in support of designation from Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, from Community Board Five, and from architectural historian, John Kriskiewicz. There was also one letter from a building resident opposed to designation. Summary The Ritz Tower Apartment Hotel was constructed in 1925 at the premier crossroads of New York’s Upper East Side, the corner of 57th Street and Park Avenue, where the exclusive shops and artistic enterprises of 57th Street met apartment buildings of ever-increasing height and luxury on Park Avenue.