Albín Polášek: Boundaries of Continents and Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 1920

ii^^ir^?!'**i r*sjv^c ^5^! J^^M?^J' 'ir ^M/*^j?r' ?'ij?^'''*vv'' *'"'**'''' '!'<' v!' '*' *w> r ''iw*i'' g;:g5:&s^ ' >i XA. -*" **' r7 i* " ^ , n it A*.., XE ETT XX " " tr ft ff. j 3ty -yj ri; ^JMilMMIIIIilllilllllMliii^llllll'rimECIIIimilffl^ ra THE lot ARC HIT EC FLE is iiiiiBiicraiiiEyiiKii! Vol. XLVII. No. 2 FEBRUARY, 1920 Serial No. 257 Editor: MICHAEL A. MIKKELSEN Contributing Editor: HERBERT CROLY Business Manager: ]. A. OAKLEY COVER Design for Stained Glass Window FAGS By Burton Keeler ' NOTABLE DECORATIVE SCULPTURES OF NEW YOKK BUILDINGS _/*' 99 .fiy Frank Owen Payne WAK MEMORIALS. Part III. Monumental Memorials . 119 By Charles Over Cornelius SOME PRINCIPLES OF SMALL HOUSE DESIGN. Part IV. Planning (Continued) .... .133 By John Taylor Boyd, Jr. ENGLISH ARCHITECTURAL DECORATION. Part XIII. 155 By Albert E. Bullock PORTFOLIO OF CURRENT ARCHITECTURE . .169 ST. PHILIP'S CHURCH, Brunswick County, N. C. Text and Meas^ ured Drawings . .181 By N. C. Curtis NOTES AND COMMENTS . .188 Yearly Subscription United States $3.00 Foreign $4.00 Single copies 35 cents. Entered May 22, 1902, as Second Class Matter, at New York, N. Y. Member Audit Bureau of Circulation. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ARCHITECTURAL RECORD COMPANY 115-119 FOFvIlt I i I IStt I, NEWINCW YORKTUKN WEST FORTIETHM STREET, H v>^ E. S. M tlli . T. MILLER, Pres. W. D. HADSELL, Vice-Pres. J. W. FRANK, Sec'y-Treas. DODGE. Vice-Pre* ' "ri ti i~f n : ..YY '...:.. ri ..rr.. m. JT i:c..."fl ; TY tn _.puc_. ,;? ,v^ Trrr.^yjL...^ff. S**^ f rf < ; ?SIV5?'Mr ^7"jC^ te :';T:ii!5ft^'^"*TiS t ; J%WlSjl^*o'*<JWii*^'J"-i!*^-^^**-*''*''^^ *,iiMi.^i;*'*iA4> i.*-Mt^*i; \**2*?STO I ASTOR DOORS OF TRINITY CHURCH. -

The Sculptures of Upper Summit Avenue

The Sculptures of Upper Summit Avenue PUBLIC ART SAINT PAUL: STEWARD OF SAINT PAUL’S CULTURAL TREASURES Art in Saint Paul’s public realm matters: it manifests Save Outdoor Sculpture (SOS!) program 1993-94. and strengthens our affection for this city — the place This initiative of the Smithsonian Institution involved of our personal histories and civic lives. an inventory and basic condition assessment of works throughout America, carried out by trained The late 19th century witnessed a flourishing of volunteers whose reports were filed in a national new public sculptures in Saint Paul and in cities database. Cultural Historian Tom Zahn was engaged nationwide. These beautiful works, commissioned to manage this effort and has remained an advisor to from the great artists of the time by private our stewardship program ever since. individuals and by civic and fraternal organizations, spoke of civic values and celebrated heroes; they From the SOS! information, Public Art Saint illuminated history and presented transcendent Paul set out in 1993 to focus on two of the most allegory. At the time these gifts to states and cities artistically significant works in the city’s collection: were dedicated, little attention was paid to long Nathan Hale and the Indian Hunter and His Dog. term maintenance. Over time, weather, pollution, Art historian Mason Riddle researched the history vandalism, and neglect took a profound toll on these of the sculptures. We engaged the Upper Midwest cultural treasures. Conservation Association and its objects conservator Kristin Cheronis to examine and restore the Since 1994, Public Art Saint Paul has led the sculptures. -

Charles Grafly Papers

Charles Grafly Papers Collection Summary Title: Charles Grafly Papers Call Number: MS 90-02 Size: 55.0 linear feet Acquisition: Donated by Dorothy Grafly Drummond Processed by: MD, 1990; JEF, 5-19-1998; MN, 1-30-2015 Note: Related collections: MS 93-04, Dorothy Grafly Papers; MS 93-05, Leopold Sekeles Papers Restrictions: None Literary Rights Literary rights were not granted to Wichita State University. When permission is granted to examine manuscripts, it is not an authorization to publish them. Manuscripts cannot be used for publication without regard for common law literary rights, copyright laws and the laws of libel. It is the responsibility of the researcher and his/her publisher to obtain permission to publish. Scholars and students who eventually plan to have their work published are urged to make inquiry regarding overall restrictions on publication before initial research. Content Note Charles Grafly was an American sculptor whose works include monumental memorials and portrait busts. Dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his correspondence relating to personal, business and other matters is collected here as well as newspaper clippings about his works, sketches and class notes, scrapbooks, photographs of his works, research materials and glass plate negatives. All file folder titles reflect the original titles of the file folders in the collection. For a detained description of the contents of each file folder, refer to the original detailed and incomplete finding aid in Box 76. Biography Born and raised in Philadelphia, Charles Grafly (1862-1929) studied under painters Thomas Eakins and Thomas Anshutz at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts between 1884-88. -

Francis Davis Millet Letters to Miss Ward and Ticknor

Francis Davis Millet letters to Miss Ward and Ticknor Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Francis Davis Millet letters to Miss Ward and Ticknor AAA.millfrad Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Francis Davis Millet letters to Miss Ward and Ticknor Identifier: AAA.millfrad Date: [undated] Creator: Millet, Francis Davis, 1846-1912 Extent: 5 Items ((partially microfilmed on 1 reel)) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Purchased 1956 with funds provided by Alfred Brayer. Available Formats 35mm microfilm reel D9 (fr. 724-732) available for use at Archives of American Art offices and through interlibrary -

Eleanor Antin by Rachel Mason

3 Laraaji I do a variety of things that keep me in a place of openness and fow – staying connected with my laughter, staying soft, staying with my breath. So the way I stay centered in New York: I visit the parks. Two of my favorite parks are Riverside Park and Central Park. I also go dancing a lot, especially dancing with shoes off, which allows me to open up, be free, and move beyond my local body sense of self into an open energetic spatial feld. So practicing, opening, and communing and interacting with a feld that is much larger than a location called New York City. So also meditation. Meditation for me means dropping, in a transcendental way, into conscious present time and being there, and just staying there not doing anything. Not thinking anything. Not processing any thought fow. Staying out of the processing of linear thought fow, staying out of the act of processing a local personal history identity, and being empty. Meditation is staying empty, staying out of local time, space, and mind. That’s how I stay centered in New York. Centered means being in my center. The center for me is not my body. The center for me is source, the self that holds me as an eternal being. So my center is spirit. Some of us refer to this as spirit or as God or as vol. 003 creative intelligence or as soul or as origin or as source, but when I am in it I no longer need to have a name for it. -

Geographical List of Public Sculpture-1

GEOGRAPHICAL LIST OF SELECTED PERMANENTLY DISPLAYED MAJOR WORKS BY DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH ♦ The following works have been included: Publicly accessible sculpture in parks, public gardens, squares, cemeteries Sculpture that is part of a building’s architecture, or is featured on the exterior of a building, or on the accessible grounds of a building State City Specific Location Title of Work Date CALIFORNIA San Francisco Golden Gate Park, Intersection of John F. THOMAS STARR KING, bronze statue 1888-92 Kennedy and Music Concourse Drives DC Washington Gallaudet College, Kendall Green THOMAS GALLAUDET MEMORIAL; bronze 1885-89 group DC Washington President’s Park, (“The Ellipse”), Executive *FRANCIS DAVIS MILLET AND MAJOR 1912-13 Avenue and Ellipse Drive, at northwest ARCHIBALD BUTT MEMORIAL, marble junction fountain reliefs DC Washington Dupont Circle *ADMIRAL SAMUEL FRANCIS DUPONT 1917-21 MEMORIAL (SEA, WIND and SKY), marble fountain reliefs DC Washington Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln Memorial Circle *ABRAHAM LINCOLN, marble statue 1911-22 NW DC Washington President’s Park South *FIRST DIVISION MEMORIAL (VICTORY), 1921-24 bronze statue GEORGIA Atlanta Norfolk Southern Corporation Plaza, 1200 *SAMUEL SPENCER, bronze statue 1909-10 Peachtree Street NE GEORGIA Savannah Chippewa Square GOVERNOR JAMES EDWARD 1907-10 OGLETHORPE, bronze statue ILLINOIS Chicago Garfield Park Conservatory INDIAN CORN (WOMAN AND BULL), bronze 1893? group !1 State City Specific Location Title of Work Date ILLINOIS Chicago Washington Park, 51st Street and Dr. GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, bronze 1903-04 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, equestrian replica ILLINOIS Chicago Jackson Park THE REPUBLIC, gilded bronze statue 1915-18 ILLINOIS Chicago East Erie Street Victory (First Division Memorial); bronze 1921-24 reproduction ILLINOIS Danville In front of Federal Courthouse on Vermilion DANVILLE, ILLINOIS FOUNTAIN, by Paul 1913-15 Street Manship designed by D.C. -

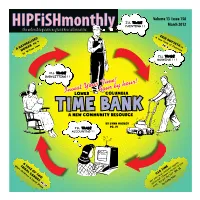

Hour by Hour!

Volume 13 Issue 158 HIPFiSHmonthlyHIPFiSHmonthly March 2012 thethe columbiacolumbia pacificpacific region’sregion’s freefree alternativealternative ERIN HOFSETH A new form of Feminism PG. 4 pg. 8 on A NATURALIZEDWOMAN by William Ham InvestLOWER Your hourTime!COLUMBIA by hour! TIME BANK A NEW community RESOURCE by Lynn Hadley PG. 14 I’LL TRADE ACCOUNTNG ! ! A TALE OF TWO Watt TRIBALChildress CANOES& David Stowe PG. 12 CSA TIME pg. 10 SECOND SATURDAY ARTWALK OPEN MARCH 10. COME IN 10–7 DAILY Showcasing one-of-a-kind vintage finn kimonos. Drop in for styling tips on ware how to incorporate these wearable works-of-art into your wardrobe. A LADIES’ Come See CLOTHING BOUTIQUE What’s Fresh For Spring! In Historic Downtown Astoria @ 1144 COMMERCIAL ST. 503-325-8200 Open Sundays year around 11-4pm finnware.com • 503.325.5720 1116 Commercial St., Astoria Hrs: M-Th 10-5pm/ F 10-5:30pm/Sat 10-5pm Why Suffer? call us today! [ KAREN KAUFMAN • Auto Accidents L.Ac. • Ph.D. •Musculoskeletal • Work Related Injuries pain and strain • Nutritional Evaluations “Stockings and Stripes” by Annette Palmer •Headaches/Allergies • Second Opinions 503.298.8815 •Gynecological Issues [email protected] NUDES DOWNTOWN covered by most insurance • Stress/emotional Issues through April 4 ASTORIA CHIROPRACTIC Original Art • Fine Craft Now Offering Acupuncture Laser Therapy! Dr. Ann Goldeen, D.C. Exceptional Jewelry 503-325-3311 &Traditional OPEN DAILY 2935 Marine Drive • Astoria 1160 Commercial Street Astoria, Oregon Chinese Medicine 503.325.1270 riverseagalleryastoria.com -

EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers

TM EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers, Top of the RockTM at Rockefeller Center is an exciting destination for New York City students. Located on the 67th, 69th, and 70th floors of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, the Top of the Rock Observation Deck reopened to the public in November 2005 after being closed for nearly 20 years. It provides a unique educational opportunity in the heart of New York City. To support the vital work of teachers and to encourage inquiry and exploration among students, Tishman Speyer is proud to present Top of the Rock Education Materials. In the Teacher Guide, you will find discussion questions, a suggested reading list, and detailed plans to help you make the most of your visit. The Student Activities section includes trip sheets and student sheets with activities that will enhance your students’ learning experiences at the Observation Deck. These materials are correlated to local, state, and national curriculum standards in Grades 3 through 8, but can be adapted to suit the needs of younger and older students with various aptitudes. We hope that you find these education materials to be useful resources as you explore one of the most dazzling places in all of New York City. Enjoy the trip! Sincerely, General Manager Top of the Rock Observation Deck 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York NY 101 12 T: 212 698-2000 877 NYC-ROCK ( 877 692-7625) F: 212 332-6550 www.topoftherocknyc.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Teacher Guide Before Your Visit . Page 1 During Your Visit . Page 2 After Your Visit . Page 6 Suggested Reading List . -

The Political and Symbolic Importance of the United States in the Creation of Czechoslovakia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Drawing borders: the political and symbolic importance of the United States in the creation of Czechoslovakia Samantha Borgeson West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Borgeson, Samantha, "Drawing borders: the political and symbolic importance of the United States in the creation of Czechoslovakia" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 342. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/342 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DRAWING BORDERS: THE POLITICAL AND SYMBOLIC IMPORTANCE OF THE UNITED STATES IN THE CREATION OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA Samantha Borgeson Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts And Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree -

Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial

Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial American Battle Monuments Commission 1 2 LOCATION The Sicily-Rome American Cemetery and Memorial lies at the north edge of the town of Nettuno, Italy, which is immediately east of Anzio, 38 miles south of Rome. There is regular train service between Rome and Nettuno. Travel one way by rail takes a little over one hour. The cemetery is located one mile north of the Nettuno railroad station, from which taxi service is available. To travel to the cemetery from Rome by automobile, the following two routes are recommended: (1) At Piazza di San Giovanni, bear left and pass through the old Roman wall to the Via Appia Nuova/route No. 7. About 8 miles from the Piazza di San Giovanni, after passing Ciampino airport, turn right onto Via Nettunense, route No. 207. Follow the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery sign and proceed past Aprilia to Anzio, Nettuno and the cemetery. (2) At Piazza de San Giovanni, bear right onto the Via dell’ Amba Aradam to Via delle Terme de Caracalla and pass through the old Roman wall. Proceed along Via Cristoforo Colombo to the Via Pontina (Highway 148). Drive south approximately 39 miles along Highway 148 and exit at Campoverde/Nettuno. Proceed to Nettuno. The cemetery is located 5 ½ miles down this road. Adequate hotel accommodations may be found in Anzio, Nettuno and Rome. HOURS The cemetery is open daily to the public from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm except December 25 and January 1. It is open on host country holidays. -

Úvod Do Etapové Hry Alois Jirásek Dalimil Ě Kroniká Kronikáě Kosmas Václav Hájek Z Liboýan Slovanští Bohové a Svatynċ

KRONIKÁě DALIMIL ALOIS JIRÁSEK ÚVOD DOETAPOVÉ HRY KRONIKÁě KOSMAS VÁCLAV HÁJEK Z LIBOýAN SLOVANŠTÍ BOHOVÉ A SVATYNċ SLOVANSKÁ SVATYNċ SLOVANSKÁ SVATYNċ SLOVANSKÝ BģH – BċLOBOG SLOVANSKÝ BģH - JAROVÍT SLOVANSKÝ BģH – BċLOBOG MODLA - SLOVANSKÝ BģH PERUN SLOVANSKÝ BģH - ýERNOBOG SLOVANSKÁ BOHYNċ – MOKOŠ SLOVANSKÁ BOHYNċ – MELUZÍNA SLOVANSKÁ BOHYNċ – MORANA SLOVANSKÝ BģH – PERUN SLOVANSKÝ BģH – PERUN SLOVANSKÝ BģH – PERUN SLOVANSKÝ BģH – PERUN SLOVANSKÝ BģH – RADEGAST SLOVANŠTÍ BOHOVÉ – VELES A PERUN SLOVANSKÝ BģH – RADEGAST SLOVANSKÝ BģH – ROD SLOVANSKÝ BģH – RADEGAST SLOVANSKÝ BģH – ROD SLOVANŠTÍ BOHOVÉ SLOVANSKÝ BģH – SVANTOVÍT SLOVANSKÝ BģH – SVANTOVÍT H – SVAROG ģ SLOVANSKÝ B SLOVANSKÝ BģH - VELES O PRAOTCI ýECHOVI ROTUNDA SVATÉHO JIěÍ NA ěÍPU ROTUNDA SVATÉHO JIěÍ NA ěÍPU MYTICKÁ HORA ě ÍP U ROUDNICENADLABEM ÍP PRAOTEC ýECH NA ěÍPU PRAOTEC ýECH NA ěÍPU VOJVODOVÉ ýECH A LECH VOJVODOVÉ ýECH, LECH A RUS 3ěÍCHOD ýECHģ NA ěÍP PRAOTEC ýECH UKAZUJE Z HORY ěÍP SVÉMU LIDU NOVOU VLAST. POHěEB PRAOTCE ýECHA O KROKOVI A JEHO DCERÁCH RODOKMEN – OD SOUDCE KROKA KE KNÍŽETI BOěIVOJOVI BUDEý – ZDE BÝVALO SÍDLO VOJVODY KROKA KROK HLEDÁ SVOJE BUDOUCÍ SÍDLO, VYŠEHRAD SÍDLO, KROK HLEDÁ SVOJE BUDOUCÍ VOJVODA KROK SE SVÝMI DCERAMI – KAZI, TETOU A LIBUŠÍ BUDEý – SÍDELNÍ MÍSTO VOJVODY KROKA JEDEN Z HRADģ KROKOVÝCH DCER - KAZÍN MÍSTO, KDESTÁVAL HRADKAZÍN TETÍN - MAPA =ěÍCENINA HRADU TETÍN =ěÍCENINA HRADU TETÍN NA TOMTO MÍSTċ STÁVAL HRAD TETÍN NA MÍSTċ KOSTELÍKA SV. JIěÍ STÁLO SLOVANSKÉ HRADIŠTċ LIBUŠÍN LIBUŠÍN – HRADIŠTċ S KOSTELEM SV. JIěÍ VYŠEHRAD VYŠEHRAD VYŠEHRADSKÁ -

'Lúčnica – Slovak National Folklore Ballet' in Melbourne, 2007

Performing Abroad: ‘Lúčnica – Slovak National Folklore Ballet’ in Melbourne, 2007 Diane Carole Roy A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University 3 August 2011 DECLARATION I, Diane Carole Roy, hereby declare that, except where otherwise acknowledged in the customary manner, and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this work is my own, and has not been submitted for a higher degree at any other university or institution. ………………………………….. ii DEDICATION Jeseñ na Slovensku Vonku je ticho, všade je šero Vo vnútri hmly vidím priatelských duchov Biele brezy so zlatými vlasmi Okolo ich nôh, zlaté koberec Táto krajina je moja sestra Niekedy rušová, niekedy pokojná Niekedy stará, niekedy mladá Ďakujem jej Di Roy 2003 Autumn in Slovakia Outside is quiet, all around is dim, Yet inside the fog I see friendly ghosts White birches with golden hair Around their feet a golden carpet This country is my sister Sometimes turbulent, sometimes peaceful Sometimes old, sometimes young I thank her iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people, without whom this work could not have been achieved: Dr Stephen Wild, for giving me the freedom to follow my lights, and for his support and friendship; Dr Johanna Rendle-Short, for her encouragement in acquiring knowledge and skills in Conversation Analysis; Dr Jozef Vakoš, who generously accepted me into the Trenčín Singers’ Choir, enabling me to be part of the choral community in Trenčín; my friends in the Trenčín Singers’ Choir, who shared their songs and joy in their traditions, and who showed me why by taking me away from the track trodden by tourists; Dr Hana Urbancová at the Institute of Musicology, and Dr Gabriela Kilánová at the Institute of Ethnology, at the Slovak Academy of Sciences, who generously gave me time, consultation and literature; Ing.