A Retrospective of the AAAI Robot Competitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administrators Guide to First Robotics Program Expenses

ADMINISTRATORS GUIDE TO FIRST ROBOTICS PROGRAM EXPENSES FIRST has 4 programs under the umbrella all foCused on inspiring more students to pursue Careers in sCienCe, teChnology, engineering, and mathematiCs. All of the programs use a robot Competition exCept the youngest group which is for K-3 and it is more of a make-it/engineering expo. Junior FIRST LEGO league (JrFLL) for students kindergarten through third grade is a researCh/design challenge and introduction to the engineering process. Kids go on a research journey, create a poster and LEGO model Present at Expo to reviewers and then all teams reCeive reCognition. Expos can be organized at the local level and a regional expo will be held in March. Costs are: ($50 - $300 per season) • $25 JrFLL program fees (annual dues) • $25 Expo registration fees • Teams Can use any LEGO, must have one moving part with a motor. FIRST does offer a large kit of parts for about $150 Registration: Never closes Register Here: http://www.usfirst.org/robotiCsprograms/jr.fll/registration Competitions/tournaments: Expo is held in the spring (RGV Local) FIRST Lego league (FLL) has a new game theme eaCh year, which also includes a student chosen project in whiCh they researCh and purpose a solution that fits their Community’s needs. The Challenge is revealed in early September eaCh year and the Competition season is from November – MarCh. Team size is limited to 10 students. Costs are: ($1,500 - $3,000 first season, then $1,000 - $2,500 per season to sustain program) • $225 FLL program fees (annual dues) • $300 -$420 Lego Mindstorms robot kit (re-usable each year) • $65 game field set-up kit (new each year) • $70 - $90 tournament registration fees • $500 - $1,000 for team apparel, meals, presentation materials, promotional items for team spirit, etc. -

Fresh Innovators Put Ideas Into Action in Robot Contest March 2010 Texas Instruments 3

WHITE PAPER Jean Anne Booth Director of WW Stellaris Marketing Fresh Innovators Put and Customer-Facing Engineering Sue Cozart Applications Engineer Ideas into Action in Robot Contest Introduction The annual FIRST® Robotics Challenge (FRC) inspires young men and women to explore applications of motors to make good use of mechanical Texas Instruments puts tools motion in imaginative ways, all in the name of a real-life game. In doing so, in the hands of creators of these high school students learn to work on a team toward a common goal, tomorrow’s machine control stretch their knowledge and exercise their creativity, apply critical thinking and systems. develop a strategic game plan, and move from theoretical and book learning to practical application of concepts, all the while learning valuable lessons that will help them in the workplace and in life throughout their adulthood. But as much as anything, the FIRST® programs are designed to interest children in science and math by making it fun and engaging through the use of robots. Texas Instruments is one of the FRC suppliers, lending its motor control technology to the materials and tool kit from which each team of students builds its robot. The Stellaris® microcontroller-based motor control system and software used by the students is from the same Jaguar® developer's kit used by professionals to build sophisticated motion-control systems used in industry day in and day out. The easy-to-use kits let naive high school students, as well as industry professionals, control various types of motors in complex systems without having to comprehend the underlying algorithms in use or details of the microcontroller (MCU) program code that is implementing the algorithms. -

CYBORG Seagulls Are Ready to Recycle

CYBORG Seagulls are ready to recycle By Edward Stratton The Daily Astorian Published: February 24, 2015 10:45AM The robotbuilding season for 25 Seaside and Astoria students on the C.Y.B.O.R.G. Seagulls robotics team ended Feb. 17. SEASIDE — Seaside High School’s studentbuilt robot SARA is in the bag and ready to recycle. The robotbuilding season for 25 Seaside and Astoria students on the CYBORG Seagulls robotics team ended Feb. 17. Now the team prepares to send 15 students to compete against 31 other teams in the divisional qualifier of the FIRST Robotics Competition starting Thursday in Oregon City. From left, Pedro Martinez, Austin JOSHUA BESSEX — THE DAILY ASTORIAN Milliren and Connor Adams, test out their SARA (Stacking Agile Robot The competition and its teams are chockfull of Assembly) robot during the CYBORG Seagulls robotic team meeting. acronyms, including Seaside’s team name The robot is designed to pick up recycling cans and cargo boxes and move them. The team will use SARA to compete in Recycle Rush, a (Creative Young Brains Observing and robotics game based on recycling Thursday through Saturday. Redefining Greatness, or CYBORG) and the Buy this photo league they compete in (For Inspiration and 1 of 6 Recognition of Science and Technology, or FIRST). For more information on the CYBORG Seagulls and the Building SARA FIRST Robotics Competition, visit www.team3673.org The CYBORG Seagulls, now in their fifth year of the competition, had from Jan. 4 to Feb. 17 to build and program SARA in their workshop. -

Acknowledgements Acknowl

2161 Acknowledgements Acknowl. B.21 Actuators for Soft Robotics F.58 Robotics in Hazardous Applications by Alin Albu-Schäffer, Antonio Bicchi by James Trevelyan, William Hamel, The authors of this chapter have used liberally of Sung-Chul Kang work done by a group of collaborators involved James Trevelyan acknowledges Surya Singh for de- in the EU projects PHRIENDS, VIACTORS, and tailed suggestions on the original draft, and would also SAPHARI. We want to particularly thank Etienne Bur- like to thank the many unnamed mine clearance experts det, Federico Carpi, Manuel Catalano, Manolo Gara- who have provided guidance and comments over many bini, Giorgio Grioli, Sami Haddadin, Dominic Lacatos, years, as well as Prof. S. Hirose, Scanjack, Way In- Can zparpucu, Florian Petit, Joshua Schultz, Nikos dustry, Japan Atomic Energy Agency, and Total Marine Tsagarakis, Bram Vanderborght, and Sebastian Wolf for Systems for providing photographs. their substantial contributions to this chapter and the William R. Hamel would like to acknowledge work behind it. the US Department of Energy’s Robotics Crosscut- ting Program and all of his colleagues at the na- C.29 Inertial Sensing, GPS and Odometry tional laboratories and universities for many years by Gregory Dudek, Michael Jenkin of dealing with remote hazardous operations, and all We would like to thank Sarah Jenkin for her help with of his collaborators at the Field Robotics Center at the figures. Carnegie Mellon University, particularly James Os- born, who were pivotal in developing ideas for future D.36 Motion for Manipulation Tasks telerobots. by James Kuffner, Jing Xiao Sungchul Kang acknowledges Changhyun Cho, We acknowledge the contribution that the authors of the Woosub Lee, Dongsuk Ryu at KIST (Korean Institute first edition made to this chapter revision, particularly for Science and Technology), Korea for their provid- Sect. -

Srinivas Akella

Srinivas Akella Department of Computer Science University of North Carolina at Charlotte Tel: (704) 687-8573 9201 University City Boulevard Email: [email protected] Charlotte, NC 28223 http://webpages.uncc.edu/sakella Citizenship: USA RESEARCH INTERESTS: Robotics and automation; Manipulation and motion planning; Multiple robot coordination; Digital microfluidics and biotechnology; Manufacturing and assembly automation; Bioinformatics and protein folding; Data analytics. EDUCATION: 1996 CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY, Pittsburgh, PA. Ph.D. in Robotics, School of Computer Science. Thesis: Robotic Manipulation for Parts Transfer and Orienting: Mechanics, Planning, and Shape Uncertainty. Advisor: Prof. Matthew T. Mason. 1993 M.S. in Robotics, School of Computer Science. 1989 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, MADRAS, India. B.Tech. in Mechanical Engineering. EXPERIENCE: 2009-present UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHARLOTTE, Charlotte, NC. Professor, Department of Computer Science (2015-present). Associate Professor, Department of Computer Science (2009-2015). 2000-2008 RENSSELAER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE, Troy, NY. Assistant Professor, Department of Computer Science. Senior Research Scientist, Department of Computer Science, and Center for Automation Technologies & Systems. 1996-1999 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN, Urbana, IL. Beckman Fellow, Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. 1989-1996 CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY, Pittsburgh, PA. Research Assistant, The Robotics Institute. Summer 1992 ELECTROTECHNICAL LABORATORY, MITI, Tsukuba, Japan. Summer Intern, Intelligent Systems Division. AWARDS: 2018 CCI Excellence in Graduate Teaching Award, College of Computing and Informatics, UNC Charlotte. 2007 Advisor, Best Student Paper Awardee, Robotics Science and Systems Conference. 2005 Rensselaer Faculty Early Research Career Honoree, RPI. 2001 NSF CAREER Award, National Science Foundation. 1999 Finalist, Best Paper Award, IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. -

World's Biggest Robot Event by Lem Fugitt

World's Biggest Robot Event by Lem Fugitt, www.robots-dreams.com oboGames 2011 was held at the San Mateo Event Center, midway between downtown San Francisco and San Jose, Rright in the heart of the high tech geek heaven called Silicon Valley. Over the three day run the event drew over 20,000 paid attendees and featured dose to 600 robots from 239 teams that had flo'Wn in from 17 different countries. There were 59 major com petition categories including robot soccer, hockey, sumo, micro mouse, kung-fu, Mech Warfare, art hots, and of course the combat robot battles that the event has become known for world-wide. Major contingents partiCipated from Mexico, Japan, Brazil, Korea, the UK, Canada, Indonesia, Colombia, and a host of other countries. As you might expect, the largest number of medals won (86) went to the USA since it was the host country and presented the least difficulty in terms of travel, expense, and time commit ment. Mexico came in second place with 16 medal wins. After sev eral years of minimal participation, Japan came back in force at RoboGames 2011 snagging 10 gold and 5 bronze medals putting them solidly in third place. WHAT MAKES RDBDGAMES DIFFERENT? RoboGames, like all great things, started from a simple, almost casual, haVing fun is always the primary objective for everyone at personal observation that has been nurtured with passion and unflag RoboGames, competitors and fans alike, a close second is to ging commitment by the event organizers, competitors, and fans over exchange ideas, inspiration, and learning. -

Multicomponent Robotic Systems and Hybrid Intelligent Systems, a Path to Autonomy

Multicomponent Robotic Systems and Hybrid Intelligent Systems, a Path to Autonomy R.J. Duro1, M. Graña2, J. de Lope3 1 Grupo Integrado de Ingeniería, Universidade da Coruña, Spain, 2 Grupo Inteligencia Computacional, Universidad del País Vasco, Spain, 3 Percepción Computacional y Robótica, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. The area of cognitive or intelligent robotics is moving from the single robot control and behavior problem to that of controlling multiple robots operating together and even collaborating in dynamic and unstructured environments. This paper introduces the topic and provides a general overview of the current state of the field of Multicomponent Robotic Systems taking into consideration the following essential problem: how to coordinate multiple robotic elements in order to perform useful tasks. The review shows where Hybrid Intelligent Systems could provide key contributions to the advancement of the field. Keywords: Intelligent robotics, multi-robot systems, modular robotics. 1 Introduction The classical concept of general purpose industrial robot, both in the case of manipulators and mobile robots, makes sense when the task to be carried out takes place in static or controlled completely structured settings. However, when the environments are highly dynamic and unstructured and when the tasks to be performed are seldom carried out in the same exact way, it is necessary to make use of robotic systems that require additional properties depending on the task. Examples of these environments are shipyards, plants for constructing unique or very large structures, civil engineering sites, etc. In these environments, work is not generally carried out as in traditional automated plants, but rather, a series of individuals or groups of specialists perform the tasks over the structure itself in an ad hoc manner. -

Maja J Matarić

Curriculum Vitae Maja J Matarić Chan Soon-Shiong Distinguished Professor of Computer Science, Neuroscience, and Pediatrics University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA [email protected] http://robotics.usc.edu/~maja Summary of contents: EDUCATION 1 PROFESSIONAL 1 TEACHING 3 RESEARCH SUPERVISION 4 INITIATIVES AS INTERIM VICE PRESIDENT OF RESEARCH 10 INITIATIVES AS VICE DEAN FOR RESEARCH 11 K-12 EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH 12 GRANTS, CONTRACTS, and GIFTS 14 HONORS AND AWARDS 23 SELECTED MEDIA COVERAGE 24 PUBLICATIONS 26 INVITED TALKS 68 SERVICE 86 TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER 93 PERSONAL 93 EDUCATION Ph.D., Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, May 1994. Dissertation: Interaction and Intelligent Behavior. Advisor: Prof. Rodney A. Brooks. Minor in Management of Technological Innovation. S.M., Computer Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Jan 1990. Thesis: A Model for Distributed Mobile Robot Environment Learning and Navigation. Advisor: Prof. Rodney A. Brooks. B.S., Computer Science, Honors and Distinction, University of Kansas, May 1987. Honors thesis: Advisor: An Intelligent Knowledge-Based System for Computer Science Curriculum Advising. Advisor: Prof. Frank Brown. Minor in Cognitive Neuroscience. PROFESSIONAL USC Distinguished Professor, Jan 2019-present. Lead, USC Viterbi K-12 STEM Center, July 2019-present. USC Interim Vice President of Research, Jan 2020-Jul 2021. Maja J Matarić CV July 2021 Co-Founder, Embodied, Inc., 2016-present. Chan Soon-Shiong Chaired Professor, Viterbi School of Engineering, University of Southern California. Oct 2012-present. Professor, Computer Science Department, Pediatrics Department, and Neuroscience Program, University of Southern California. Apr 2006-present. Founding Director, Robotics and Autonomous Systems Center (RASC, rasc.usc.edu), (originally Robotics and Embedded Systems (cres.usc.edu), USC. -

Projects in the Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Fields

Projects in the Robotics and Artificial Intelligence Fields New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization Robot and Artificial Intelligence Technology Department 19F MUZA Kawasaki Central Tower, 1310 Omiya-cho, Saiwai-ku Kawasaki City, Kanagawa 212-8554 Japan Tel: +81-44-520-5241 Fax: +81-44-520-5243 URL: https://www.nedo.go.jp/english/index.html November. 2020(1st Edition) Overview of NEDO IntroductionofRobotandArtificialIntelligenceTechnologyDepartment About NEDO Missions and Activities Overview NEDO of ● NEDO is a national research and development agency that creates innovation by promoting technological development necessary for realization of a sustainable society. Message from the Director General ● NEDO acts as an innovation accelerator to contribute to the resolution of social issues by developing and demonstrating high-risk innovative technologies having practical application. Japan’s robot industry has developed with the focus on industrial robots for automobile, electric appliance and other manufacturing industries. However, due to the decreased labor NEDO’s Missions force associated with the dwindling birth rates and aging population, and the pursuit of Addressing energy and improved productivity rates, movements toward the utilization of robots in various fields other Enhancing industrial than large-scale manufacturing have expanded. global environmental technology problems To address such expansion of the robot utilization fields promptly, NEDO has been promoting NEDO actively undertakes the development of new energy and With the aim of raising the level of industrial technology, energy conservation technologies. It also conducts research to NEDO pursues research and development of advanced new research and development of robots to be applied in various fields since initiating robot verify technical results. -

Experiences in Deploying Test Arenas for Autonomous Mobile Robots

Experiences in Deploying Test Arenas for Autonomous Mobile Robots Adam Jacoff, Elena Messina, John Evans Intelligent Systems Division National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 ABSTRACT and henceforth, the RoboCup Federation [3] will use the arenas to host their newly formed The National Institute of Standards and Technology RoboCupRescue league competitions. A has created a set of reference test arenas for evaluating discussion of the details of these competitions is the performance of mobile autonomous robots contained in Section 3 of this paper. performing urban search and rescue tasks. The arenas are intended to help accelerate the robotic research There are three sets of customers for the arenas. community’s advancement of mobile robot The first are researchers, who need testing capabilities. The arenas have been deployed in two opportunities. The repeatable obstacles (sensory competitions thus far and are also being used by researchers to test their systems’ capabilities. We and physical) that are focussed towards mobile describe the arenas, their use in competitions and our robotic perception and intelligent behavior near-term and long-term plans for the arenas. provide them with challenges for their robots. The second are the sponsors of research. They can use the arenas for validation exercises to 1. INTRODUCTION objectively evaluate robots in structured, repeatable, representative environments. The The National Institute of Standards and arenas can be used to validate robotic purchases, Technology (NIST) has been collaborating with identify strengths and weaknesses in systems, other government agencies and university and compare the cost effectiveness of different researchers to develop methods of evaluating and approaches. -

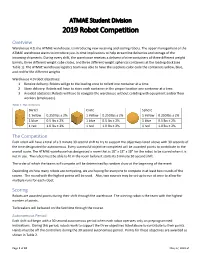

2019 Robot Competition

ATMAE Student Division 2019 Robot Competition Overview Warehouse 4.0, the ATMAE warehouse, is introducing new receiving and storing robots. The upper management of the ATMAE warehouse wants to introduce just-in-time implications to help streamline deliveries and storage of the incoming shipments. During every shift, the warehouse receives a delivery of nine containers of three different weight barrels, three different weight cube crates, and three different weight spherical containers at the loading dock (see Table 1). The ATMAE warehouse logistics team was able to have the suppliers color code the containers yellow, blue, and red for the different weights. Warehouse 4.0 robot objectives: 1. Receive delivery: Robots will go to the loading zone to collect one container at a time. 2. Store delivery: Robots will have to store each container in the proper location one container at a time. 3. Avoided obstacles: Robots will have to navigate the warehouse without colliding with equipment and/or floor workers (employees). Table 1: The containers Barrel Crate Sphere 1 Yellow 0.250 lbs ± 2% 1 Yellow 0.250 lbs ± 2% 1 Yellow 0.250 lbs ± 2% 1 blue 0.5 lbs ± 2% 1 blue 0.5 lbs ± 2% 1 blue 0.5 lbs ± 2% 1 red 1.0 lbs ± 2% 1 red 1.0 lbs ± 2% 1 red 1.0 lbs ± 2% The Competition Each robot will have a total of a 3 minute 30 second shift to try to support the objectives listed above with 30 seconds of the time designated for autonomous. Every successful objective completed will be awarded points to contribute to the overall score. -

CLAWAR Robotics Competition & Exhibition CLAWAR Robotics

CLAWAR Robotics Competition & Exhibition CLAWAR Robotics Competition & Exhibition is a competition challenging the research and development community, worldwide, to present their research results in the form of a technical presentation and a public demo. The scope of the demos encompasses physical robots (one or more), mobile or not, land, aquatic or aerial. The acceptance of teams/demos may be limited due to the availability of technical conditions at the site. Each demo will be evaluated by a jury of prominent individuals with a strong connection to robotics with respect to their: technical-scientific quality; application potential; capability to present the solution to the public; and quality and success of the demo. The top team will be declared the winner of the competition. The CLAWAR Robotics competition will be held during the CLAWAR 2019 Conference in Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia. Category CLAWAR Exhibition & Award 1. Primary School 2. Secondary School/Matriculation/ Vocational School (Aged 18 and below) 3. Open/University/College University/College/Vocational College (Aged 19 and above) CLAWAR Robotics Competition -Robosumo (open category) Fee Structure Category Local International (USD) Early Bird Normal Early Bird Normal CLAWAR International Exhibition & Award Primary* 200 300 150 175 Secondary 300 400 175 200 School/Matriculation/ Vocational School (Aged 18 and below)* Open/University/College 500 600 200 225 University/College/Vocational College (Aged 19 and above)* CLAWAR International Robo Sumo Competition Robo Sumo* 150