MHQ Winter 2101 First Lieutenant R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doolittle and Eaker Said He Was the Greatest Air Commander of All Time

Doolittle and Eaker said he was the greatest air commander of all time. LeMayBy Walter J. Boyne here has never been anyone like T Gen. Curtis E. LeMay. Within the Air Force, he was extraordinarily successful at every level of com- mand, from squadron to the entire service. He was a brilliant pilot, preeminent navigator, and excel- lent bombardier, as well as a daring combat leader who always flew the toughest missions. A master of tactics and strategy, LeMay not only played key World War II roles in both Europe and the Pacific but also pushed Strategic Air Command to the pinnacle of great- ness and served as the architect of victory in the Cold War. He was the greatest air commander of all time, determined to win as quickly as possible with the minimum number of casualties. At the beginning of World War II, by dint of hard work and train- ing, he was able to mold troops and equipment into successful fighting units when there were inadequate resources with which to work. Under his leadership—and with support produced by his masterful relations with Congress—he gained such enor- During World War II, Gen. Curtis E. LeMay displayed masterful tactics and strategy that helped the US mous resources for Strategic Air prevail first in Europe and then in the Pacific. Even Command that American opponents Soviet officers and officials acknowledged LeMay’s were deterred. brilliant leadership and awarded him a military deco- “Tough” is always the word that ration (among items at right). springs to mind in any consideration of LeMay. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

Smithsonian and the Enola

An Air Force Association Special Report The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay The Air Force Association The Air Force Association (AFA) is an independent, nonprofit civilian organiza- tion promoting public understanding of aerospace power and the pivotal role it plays in the security of the nation. AFA publishes Air Force Magazine, sponsors national symposia, and disseminates infor- mation through outreach programs of its affiliate, the Aerospace Education Founda- tion. Learn more about AFA by visiting us on the Web at www.afa.org. The Aerospace Education Foundation The Aerospace Education Foundation (AEF) is dedicated to ensuring America’s aerospace excellence through education, scholarships, grants, awards, and public awareness programs. The Foundation also publishes a series of studies and forums on aerospace and national security. The Eaker Institute is the public policy and research arm of AEF. AEF works through a network of thou- sands of Air Force Association members and more than 200 chapters to distrib- ute educational material to schools and concerned citizens. An example of this includes “Visions of Exploration,” an AEF/USA Today multi-disciplinary sci- ence, math, and social studies program. To find out how you can support aerospace excellence visit us on the Web at www. aef.org. © 2004 The Air Force Association Published 2004 by Aerospace Education Foundation 1501 Lee Highway Arlington VA 22209-1198 Tel: (703) 247-5839 Produced by the staff of Air Force Magazine Fax: (703) 247-5853 Design by Guy Aceto, Art Director An Air Force Association Special Report The Smithsonian and the Enola Gay By John T. Correll April 2004 Front cover: The huge B-29 bomber Enola Gay, which dropped an atomic bomb on Japan, is one of the world’s most famous airplanes. -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

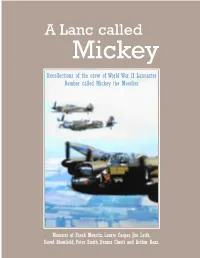

A Lanc Called Mickey

A Lanc called Mickey Recollections of the crew of World War II Lancaster Bomber called Mickey the Moocher Memoirs of Frank Mouritz, Laurie Cooper, Jim Leith, David Blomfield, Peter Smith, Dennis Cluett and Arthur Bass. Recollections of a crew of World War II Lancaster Bomber called Mickey the Moocher Contents Introduction .............................................................................. 2 Abbreviations Used ................................................................... 3 Mickey the Moocher .................................................................. 5 Frank Mouritz ............................................................................ 7 No 5 Initial Training School, Clontarf .......................................................... 7 No 9 Elementary Flying Training School, Cunderdin .................................... 10 No 4 Service Flying Training School, Geraldton .......................................... 11 No 5 Embarkation Depot ......................................................................... 12 No 1 Embarkation Depot, Ascot Vale ......................................................... 13 At Sea .................................................................................................. 14 Across America ...................................................................................... 16 Crossing the Atlantic .............................................................................. 17 United Kingdom, First Stop Brighton ........................................................ -

Weapon Physics Division

-!! Chapter XV WEAPON PHYSICS DIVISION Introduction 15.1 At the time of its organization in August 1944, the Weapon Physics or G Division (G for gadget, code for weapon) was given a directive to carry out experiments on the critical assembly of active materials, to de- vise methods for the study of the implosion, and to exploit these methods to gain information about the implosion. In April 1945, the G Division directive was extended to fnclude the responsibility for the design and procurement of the hnplosion tamper, as well as the active core. In addition to its primary work with critical assemblies and implosion studies, G Division undertook the design and testing of an implosion initiator and of electric detonators for the high explosive. The Electronics Group was transferred from the Experi- mental Physics Division to G Division, and the Photographic Section of the Ordnance Division became G Divisionts Photographic Group. 15.2 The initial organization of the division, unchanged during the year which this account covers, was as follows: G-1 Critical Assemblies O. R. Frisch G-2 The X-Ray Method L. W. Parratt G-3 The Magnetic Method E. W. McMillan G-4 Electronics W. A. Higginbotham G-5 The Betatron Method S. H. Neddermeyer G-6 The RaLa Method B. ROSSi G-7 Electric Detonators L. W. Alvarez G-8 The Electric Method D. K. Froman G-9 (Absorbed in Group G-1) G-10 Initiator Group C. L. Critchfield G-n Optics J. E. Mack - 228 - 15.3 For the work of G Division a large new laboratory building was constructed, Gamma Building. -

The Bombsight War: Norden Vs. Sperry

The bombsight war: Norden vs. Sperry As the Norden bombsight helped write World War II’s aviation history, The less-known Sperry technology pioneered avionics for all-weather flying Contrary to conventional wisdom, Carl three axes, and was often buffeted by air turbulence. L. Norden -- inventor of the classified Norden The path of the dropped bomb was a function of the bombsight used in World War I! -- did not acceleration of gravity and the speed of the plane, invent the only U.S. bombsight of the war. He modified by altitude wind direction, and the ballistics invented one of two major bombsights used, of the specific bomb. The bombardier's problem was and his was not the first one in combat. not simply an airborne version of the artillery- That honor belongs to the top secret gunner's challenge of hitting a moving target; it product of an engineering team at involved aiming a moving gun with the equivalent of Sperry Gyroscope Co., Brooklyn, N. Y. The a variable powder charge aboard a platform evading Sperry bombsight out did the Norden in gunfire from enemy fighters. speed, simplicity of operation, and eventual Originally, bombing missions were concluded technological significance. It was the first by bombardier-pilot teams using pilot-director bombsight built with all-electronic servo systems, so it responded indicator (PDI) signals. While tracking the target, the bombardier faster than the Norden's electromechanical controls. It was much would press buttons that moved a needle on the plane's control simpler to learn to master than the Norden bombsight and in the panel, instructing the pilot to turn left or right as needed. -

Avro Lancaster: the Survivors Free

FREE AVRO LANCASTER: THE SURVIVORS PDF Glenn White | 200 pages | 30 Dec 2010 | Mushroom Model Publications | 9788389450470 | English | Poland MMP Books » Książki Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives. Avro Lancaster. KB Read more about KB Type of aircraft: Avro Lancaster. Registration: B Flight Phase: Takeoff climb. Flight Type: Training. Survivors: Yes. Site: Airport less than 10 km from airport. MSN: Santa Cruz. Country: Argentina. Region: South America. Crew on board: 6. Pax on board: 0. Total fatalities: 0. Aircraft flight hours: Circumstances: Crashed during takeoff and came to rest in flames. All six crew members escaped uninjured. Registration: Flight Phase: Flight. Flight Type: Military. Survivors: No. Site: Plain, Valley. Schedule: Paris — Istres — Agadir. Marrakech-Tensift- El Haouz. Country: Morocco. Region: Africa. Crew on board: 5. Pax on board: Total fatalities: The airplane was also coded WU Probable cause: Engine fire in flight. Flight Type: Test. Schedule: Malmen - Malmen. Country: Sweden. Region: Europe. Crew on board: 4. Total fatalities: 2. Circumstances: The crew two pilots and two engineers were involved in a local Avro Lancaster: The Survivors flight following engine maintenance and modification. Shortly after takeoff from Malmen AFB, while climbing, the engine number one caught fire. Both engineers were able to bail out and were found alive while both pilots were killed when the aircraft crashed in a huge explosion in Slaka Kyrka, about 4 km south of the airbase. Probable cause: Loss of control during initial climb following fire on engine number one. Crash of an Avro Lancaster B. Registration: RE Schedule: Newquay - Newquay. Country: United Kingdom. The captain decided to abandon the takeoff procedure but as the aircraft started to skid, he raised the undercarriage, causing the aircraft to sink on runway and to slid for dozen yards before coming to rest. -

Evolutionary Agent-Based Simulation of the Introduction of New Technologies in Air Traffic Management

Evolutionary Agent-Based Simulation of the Introduction of New Technologies in Air Traffic Management Logan Yliniemi Adrian Agogino Kagan Tumer Oregon State University UCSC at NASA Ames Oregon State University Corvallis, OR, USA Moffett Field, CA, USA Corvallis, OR, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT new piece of technology to fit into this framework is a challenging Accurate simulation of the effects of integrating new technologies process in which many unforeseen consequences. Thus, the abil- into a complex system is critical to the modernization of our anti- ity to simulate new technologies within an air traffic management quated air traffic system, where there exist many layers of interact- framework is of the utmost importance. ing procedures, controls, and automation all designed to cooperate One approach is to create a highly realistic simulation for the with human operators. Additions of even simple new technologies entire system [13, 14], but in these cases, every technology in the may result in unexpected emergent behavior due to complex hu- system must be modeled, and their interactions must be understood man/machine interactions. One approach is to create high-fidelity beforehand. If this understanding is lacking, it may be difficult human models coming from the field of human factors that can sim- to integrate them into such a framework [16]. With a sufficiently ulate a rich set of behaviors. However, such models are difficult to complex system, missed interactions become a near-certainty. produce, especially to show unexpected emergent behavior com- Another approach is to use an evolutionary approach in which a ing from many human operators interacting simultaneously within series of simple agents evolves a model the complex behavior of the a complex system. -

![The American Legion [Volume 125, No. 2 (August 1988)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2960/the-american-legion-volume-125-no-2-august-1988-1592960.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 125, No. 2 (August 1988)]

Haband's "Best-Step™" J|k ounce In I PAIRS OnUtO M for only 1 Deluxe Dress BOOTS Mahogany Tassel FINEST DRESS SHOE VALUE IN AMERICA! You don't have to pay $50 to $80 at some fancy Italian Bootery! COME TO HABAND. Update your appearance while you SAVE! Take of fine Executive Black any these Dress Shoes for our famous Oxford low price: 2 pairs for $29.95. Boots only $3 a pair more. Mix styles, colors, sizes any way you wish. Order with a friend! Any way you do it, the more you buy the better the price. BEST QUALITY COMPONENTS TOO! • Unique Flexi-Comfort™ design for softness! Brown • Wipe clean all-weather never-need-a-shine uppers. Loafer • Non-slip shock-absorbing lifetime soles and heels. • Meticulous detailing throughout. • Soft insides & full innersoles. BE READY, FRIEND, TO BE DELIGHTED! YES! Haband Company is one of America's very largest shoe retailers, selling hundreds of thousands of pairs direct by mail to men in every city and EVEN town in America. Send us your check today, and we will be delighted to ntroduce ourselves to you with the most outstanding shoe value of your life. Any TWO pairs, prices starting low as $29.95! BOOTS! "Best Step" Executive 95 Only $3 a pair more gets you these | |"X Boots only Deluxe Executive Dress Boots! only // njl $3 a pair | U1T6SS O1IO6S additional te the luxury detailing, the elegant trim, . e slightly higher Boot heel to make you I 3 pairs of shoes $44.25 4/S59.50 5/S74.25 ou look taller and slimmer, easy-on/ | HABAND wipe easy-off full side zipper. -

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron's

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron’s Experience during the Development of World War II Tactical Air Power by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 14, 2013 Keywords: World War II, fighter squadrons, tactical air power, P-47 Thunderbolt, European Theater of Operations Copyright 2013 by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce Approved by William Trimble, Chair, Alumni Professor of History Alan Meyer, Assistant Professor of History Mark Sheftall, Associate Professor of History Abstract During the years between World War I and World War II, many within the Army Air Corps (AAC) aggressively sought an independent air arm and believed that strategic bombardment represented an opportunity to inflict severe and dramatic damages on the enemy while operating autonomously. In contrast, working in cooperation with ground forces, as tactical forces later did, was viewed as a subordinate role to the army‘s infantry and therefore upheld notions that the AAC was little more than an alternate means of delivering artillery. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for a significantly expanded air arsenal and war plan in 1939, AAC strategists saw an opportunity to make an impression. Eager to exert their sovereignty, and sold on the efficacy of heavy bombers, AAC leaders answered the president‘s call with a strategic air doctrine and war plans built around the use of heavy bombers. The AAC, renamed the Army Air Forces (AAF) in 1941, eventually put the tactical squadrons into play in Europe, and thus tactical leaders spent 1943 and the beginning of 1944 preparing tactical air units for three missions: achieving and maintaining air superiority, isolating the battlefield, and providing air support for ground forces. -

Conventional Weapons

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 45 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2009 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group Windrush House Avenue Two Station Lane Witney OX28 4XW 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman FRAeS Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore G R Pitchfork MBE BA FRAes *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain A J Byford MA MA RAF *Wing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS RFC BOMBS & BOMBING 1912-1918 by AVM Peter Dye 8 THE DEVELOPMENT OF RAF BOMBS, 1919-1939 by 15 Stuart Hadaway RAF BOMBS AND BOMBING 1939-1945 by Nina Burls 25 THE DEVELOPMENT OF RAF GUNS AND 37 AMMUNITION FROM WORLD WAR 1 TO THE