In Defense of Romantic Fiction Ann Margolis Pace University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond the Bodice Ripper: Innovation and Change in The

© 2014 Andrea Cipriano Barra ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BEYOND THE BODICE RIPPER: INNOVATION AND CHANGE IN THE ROMANCE NOVEL INDUSTRY by ANDREA CIPRIANO BARRA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Sociology Written under the direction of Karen A. Cerulo And approved by _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey OCTOBER 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Beyond the Bodice Ripper: Innovation and Change in the Romance Novel Industry By ANDREA CIPRIANO BARRA Dissertation Director: Karen A. Cerulo Romance novels have changed significantly since they first entered the public consciousness. Instead of seeking to understand the changes that have occurred in the industry, in readership, in authorship, and in the romance novel product itself, both academic and popular perception has remained firmly in the early 1980s when many of the surface criticisms were still valid."Using Wendy Griswold’s (2004) idea of a cultural diamond, I analyze the multiple and sometimes overlapping relationships within broader trends in the romance industry based on content analysis and interviews with romance readers and authors. Three major issues emerge from this study. First, content of romance novels sampled from the past fourteen years is more reflective of contemporary ideas of love, sex, and relationships. Second, romance has been a leader and innovator in the trend of electronic publishing, with major independent presses adding to the proliferation of subgenres and pushing the boundaries of what is considered romance. Finally, readers have a complicated relationship with the act of reading romance and what the books mean in their lives. -

Romantic Reads

Contemporary Extra Spicy Sandra Brown Cherry Adair Meg Cabot Maya Banks Robyn Carr Sylvia Day Katherine Center Helen Hardt Samantha Chase E.L. James Jenny Colgan Regina Kyle Jackie Collins Jennifer Crusie Barbara Delinsky istorical Jude Deveraux (Edilean Series) Stephanie Evanovich Lenora Bell (Victorian) Emily Giffin Jude Deveraux (Montgomery-Taggert Shelley Shepard Gray Series/Medieval) Kristan Higgins Alyson McLayne (Medieval) Helen Hoang Joanna Shupe (Gilded Age) Abby Jimenez Lisa Kleypas (Friday Harbor Series) Literary Romance Kevin Kwan Christina Lauren Sarah Addison Allen Debbie Macomber Isabel Allende Susan Mallery Jane Austen Jill Mansell Charlotte Bronte Jenn McKinlay Emily Bronte Judith McNaught A.S. Byatt Jojo Moyes E.M. Forster Brenda Novak Diana Gabaldon Priscilla Oliveras Gabriel Garcia Marquez Susan Elizabeth Phillips Elizabeth Gaskell Nora Roberts Elizabeth George Sheila Roberts Thomas Hardy Jill Shalvis Alice Hoffman Nicholas Sparks Victoria Holt Anna Todd D.H. Lawrence Abbi Waxman Adriana Trigiani Jennifer Weiner Anne Tyler Susan Wiggs Edith Wharton Sherryl Woods Evelyn Waugh Regency Romantic Suspense Nancy Campbell Allen Sandra Brown Katharine Ashe Christina Dodd Jane Ashford Karen Harper Mary Balogh Linda Howard Lenora Bell Lisa Jackson Anna Bennett Jayne Ann Krentz Lisa Berne Kat Martin Jo Beverley Brenda Novak Kelly Bowen Erica Spindler Anna Bradley Grace Burrowes Christy Carlyle Sci-Fi, Fantasy, and Marion Chesney Tessa Dare -

C:\Documents and Settings\Msnll\My Documents\Voyagerreports

Swofford Popular Reading Collection September 1, 2011 Title Author Item Enum Copy #Date of Publication Call Number "B" is for burglar / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11994 PBK G737 bi "F" is for fugitive / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11990 PBK G737 fi "G" is for gumshoe / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue 11991 PBK G737 gi "H" is for homicide / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11992 PBK G737 hi "I" is for innocent / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11993 PBK G737 ii "K" is for killer / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11995 PBK G737 ki "L" is for lawless / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11996 PBK G737 li "M" is for malice / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11998 PBK G737 mi "N" is for noose / Sue Grafton. Grafton, Sue. 11999 PBK G737 ni "O" is for outlaw Grafton, Sue 12001 PBK G737 ou 10 lb. penalty / Dick Francis. Francis, Dick. 11998 PBK F818 te 100 great fantasy short short stories / edited by Isaac 11985 PBK A832 gr Asimov, Terry Carr, and Martin H. Greenberg, with an introduction by Isaac Asimov. 1001 most useful Spanish words / Seymour Resnick. Resnick, Seymour. 11996 PBK R434 ow 1022 Evergreen Place / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12010 PBK M171 te 13th warrior : the manuscript of Ibn Fadlan relating his Crichton, Michael, 1942- 11988 PBK C928 tw experiences with the Northmen in A.D. 922. 16 Lighthouse Road / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. 12001 PBK M171 si 1776 / David McCullough. McCullough, David G. 12006 PBK M133 ss 1st to die / James Patterson. Patterson, James, 1947- 12002 PBK P317.1 fi 204 Rosewood Lane / Debbie Macomber. Macomber, Debbie. -

Global Infatuation: Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts. the Case of Harlequin Enterprises and Sweden

GlobalGlobal Infatuation InfatuationExplorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts the case of harlequin enterprises and sweden HemmungsEvaEva Hemmungs Wirtén Wirtén Skrifter utgivna av Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala Publications from the Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University Nr 38 Global Infatuation Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts the case of harlequin enterprises and sweden Eva Hemmungs Wirtén Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University Uppsala 1998 Till Mamma och minnet av Pappa Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in literature presented at Uppsala University in 1998 Abstract Hemmungs Wirtén, E. 1998: Global Infatuation: Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts. The Case of Harlequin Enterprises and Sweden. Skrifter utgivna av Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala. Publications from the Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University, 38. 272 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-85178-28-4. English text. This dissertation deals with the Canadian category publisher Harlequin Enterprises. Operating in a hundred markets and publishing in twenty-four languages around the world, Harlequin Enterprises exempliıes the increasingly transnational character of publishing and the media. This book takes the Stockholm-based Scandinavian subsidiary Förlaget Harlequin as a case-study to analyze the complexities involved in the transposition of Harlequin romances from one cultural context into another. Using a combination of theoretical and empirical approaches it is argued that the local process of translation and editing – here referred to as transediting – has a fundamental impact on how the global book becomes local. -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

Julia Quinn, Eloisa James, Connie Brockway

The Lady Most Willing...: A Novel in Three Parts; Julia Quinn, Eloisa James, Connie Brockway 0062107402, 9780062107404; 384 pages; Harper Collins, 2012; 2012; The Lady Most Willing...: A Novel in Three Parts; Julia Quinn, Eloisa James, Connie Brockway; After the success of The Lady Most Likely, New York Times bestselling authors Julia Quinn, Eloisa James, and Connie Brockway have joined together once again, but this time to ask the question, who is The Lady Most Willing?When Laird Taran Ferguson’s nephews refuse to wed and secure his birthright, he takes matters into his own hands, raiding a ball and kidnapping four likely brides—a bonny lass, an heiress with a slight reputation problem, a rich English beauty, and a maiden without a name or a fortune. But which one is ready to fall in love with the Scottish lord? Add a very angry duke, a decrepit castle, and a fierce Highland storm that is holding all of Taran’s “guests― captive to the mix, and readers will find themselves transported to a world of temptation, passion, and new and unexpected love. This historical romance novel in three parts—a single story with three compelling voices—is one that will not soon be forgotten. file download mari.pdf ISBN:9781416506812; 384 pages; Connie Brockway; Fiction; My Surrender; CONNIE BROCKWAY sweeps readers into the ballrooms and boudoirs of Regency-era London and on to the Scottish Highlands in a sizzling tale of scandal, deception, and breathtaking; May 27, 2005 In the third chapter of Connie Brockways exquisite Highland trilogy, a notorious temptress discovers that nothing settles an old score like true love. -

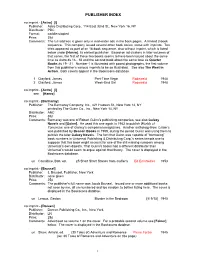

Publisher Index

PUBLISHER INDEX no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] Publisher: Astro Distributing Corp., 114 East 32nd St., New York 16, NY Distributor: PDC Format: saddle-stapled Price: 35¢ Comments: The full address is given only in mail-order ads in the back pages. A limited 2-book sequence. This company issued several other book series, some with imprints. Ten titles appeared as part of an 18-book sequence, also without imprint, which is listed below under [Hanro], its earliest publisher. Based on ad clusters in later volumes of that series, the first of these two books seems to have been issued about the same time as Astro #s 16 - 18 and the second book about the same time as Quarter Books #s 19 - 21. Number 1 is illustrated with posed photographs, the first volume from this publisher’s various imprints to be so illustrated. See also The West in Action. Both covers appear in the Bookscans database. 1 Clayford, James Part-Time Virgin Rodewald 1948 2 Clayford, James W eek -End Girl Rodewald 1948 no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] see [Hanro] no imprint - [Barmaray] Publisher: The Barmaray Company, Inc., 421 Hudson St., New York 14, NY printed by The Guinn Co., Inc., New York 14, NY Distributor: ANC Price: 35¢ Comments: Barmaray was one of Robert Guinn’s publishing companies; see also Galaxy Novels and [Guinn]. He used this one again in 1963 to publish Worlds of Tomorrow, one of Galaxy’s companion magazines. Another anthology from Collier’ s was published by Beacon Books in 1959, during the period Guinn was using them to publish the later Galaxy Novels. -

Care Needs of Women: Tending His Flock

#110: Care Needs of Women: Tending His Flock Recommended by the Writer: Abuse 1. Allender, Dr. Dan B. The Wounded Heart: Hope for Adult victims of Childhood Sexual Abuse . Colorado Springs: NavPress,1995, 2. Evans, Patricia. The Verbally Abusive Relationship . Avon: Adams Media Corporation, 1996. 3. Feldmeth, J.R. & M. Finley. We Weep for Ourselves and Our Children: A Christian Guide for Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse . San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990. 4. Heitritter, Lynn & Jeanette Vought. Helping Victims of Sexual Abuse: A Sensitive Biblical Guide for Counselors, Victims, and Families. Minneapolis: Bethany House, 2006. 5. Pillari, V. Scapegoating in Families: Intergenerational Patterns of Physical and Emotional Abuse . New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1991. Christian Caregiving 1. Collins, Gary R. How To Be a People Helper . Carol Springs: Tyndale House Publisher, Inc., 1995. 2. Haugk, Kenneth C. Christian Caregiving. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984. Depression 1. Biebel, David B. D. Min. & Harold G. Koenig, M.D. New Light on Depression: Help, Hope, and Answers for the Depressed & Those Who Love Them. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004. 2. Poinsett, Brenda. When the Saints Sing the Blues: Understanding Depression through the Lives of Job, Naomi, Paul, and Others . Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2006. Divorce 1. Carter, Les, Ph.D. Grace and Divorce . San Francisco: Jossey-B ass, 2005. 2. Smoke, Jim. Growing Through Divorce . Irving: Harvest House, 1976. Eating Disorders 1. Minirth, Dr. Frank, Dr. Paul Meier, Dr. Robert Hemfelt, Dr. Sharon Sneed, and Don Hawkins. Love Hunger: Recovery from Food Addiction . New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1990. 2. Vredevelt, Pam, Dr. Deborah Newman, Harry Beverly & Dr. -

Uncovering and Recovering the Popular Romance Novel A

Uncovering and Recovering the Popular Romance Novel A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jayashree Kamble IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Timothy Brennan December 2008 © Jayashree Sambhaji Kamble, December 2008 Acknowledgements I thank the members of my dissertation committee, particularly my adviser, Dr. Tim Brennan. Your faith and guidance have been invaluable gifts, your work an inspiration. My thanks also go to other members of the faculty and staff in the English Department at the University of Minnesota, who have helped me negotiate the path to this moment. My graduate career has been supported by fellowships and grants from the University of Minnesota’s Graduate School, the University of Minnesota’s Department of English, the University of Minnesota’s Graduate and Professional Student Assembly, and the Romance Writers of America, and I convey my thanks to all of them. Most of all, I would like to express my gratitude to my long-suffering family and friends, who have been patient, generous, understanding, and supportive. Sunil, Teresa, Kristin, Madhurima, Kris, Katie, Kirsten, Anne, and the many others who have encouraged me— I consider myself very lucky to have your affection. Shukriya. Merci. Dhanyavad. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Shashikala Kamble and Sambhaji Kamble. ii Abstract Popular romance novels are a twentieth- and twenty-first century literary form defined by a material association with pulp publishing, a conceptual one with courtship narrative, and a brand association with particular author-publisher combinations. -

Book Expo America History Will Be Kind to Me, for I Intend to Write It

june-july History is in the details By Brian Thornton Book Expo America History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it. - Winston Churchill Let me tell you, having read both Churchill’s memoirs and some of the “history” he wrote, the guy wasn’t kidding about history written by him being kind to him. And while Churchill’s fictionalization of history was equal parts intentional and unintentional, there is a growing group of authors who intentionally blend not only history and fiction, but history and crime. These writers of “historical mysteries” include such literary lights as Steven Saylor, Anne Perry, Jacqueline Winspear, Jason Goodwin, Steve Hockensmith and Louis Bayard (the first two are past Edgar Award winners, Winspear is a 2004 Edgar nominee and the last three are 2007 Edgar nominees). Whereas research has always played a large role in mystery writing, historical research can be a different animal altogether. I recently asked several historical mystery writers to name their favorite internet research tool, the one that most readily accomplished the twin goal of saving them time and giving them a maximum return on their investment. Hockensmith (Holmes on the Range, On the Wrong Track) Chuck Zito and Bill Bryan greet their fans. (Photos by Margery Flax) points to an overlooked sector of internet research: Yahoo groups. “For my latest book, I needed a ton of material on trains and railroad lines of the 1890s,” he says. After checking “literally dozens of train books” out of the library, Hockensmith still wasn’t getting what he needed, so he joined several Yahoo groups that catered to railroad enthusiasts and hit pay dirt. -

Slavery and Human Trafficking Statement for Financial Year2018

Slavery And Human Trafficking Statement For Financial Year 2018 This statement sets out the steps that we, News Corp, have taken across the News Corp Group to ensure that slavery or human trafficking is not taking place in any part of our own business or supply chains. This statement relates to actions and activities during the financial year 2018, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018. STATEMENT FROM CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER News Corp recognizes the importance of combating slavery and human trafficking, a crime that affects communities and individuals across the globe. We endorse a purposeful mission to improve the lives of others, as well as a passionate commitment to opportunity for all. As such, we are totally opposed to such abuses of a person’s freedoms both in our direct operations, our indirect operations and our supply chains. We are proud of the business standards News Corp upholds, as set out in the News Corp Standards of Business Conduct (the News Corp SOBC), see http://newscorp.com/corporate- governance/standards-of-business-conduct/) and are proud of the steps we have taken, and are committed to build upon, to ensure that slavery and human trafficking have no place either in our own business or our supply chains. Robert Thomson CEO, News Corp MEANING OF SLAVERY AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING For the purposes of this statement, slavery and human trafficking is based on the definitions set out in the Modern Slavery Act 2015 (the Act). We recognize that slavery and human trafficking can occur in many forms, such as forced labor, child labor, domestic servitude, sex trafficking and workplace abuse and it can include the restriction of a person’s freedom of movement whether that be physical, non-physical or, for example, by the withholding of a worker’s identity papers. -

Page 1 NAPA VALLEY UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT - INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS ADOPTION LIST

NAPA VALLEY UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT - INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS ADOPTION LIST SUBJECT TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER CR SUBJECT COURSE # GRADE AD CODE BK ISBN # ID# AGRICULTURE Agriculture Mechanics Fundamentals Ray V. Herren/Elmer L. Cooper DelMar Publish 2002 AGRI CTE770 9 - 12 2003 B 2943 0-7668-1410-6 Agriscience Fundamentals and Applications Elmer Cooper DelMar Publish 1997 AGRI 9 - 12 1997 B 2716 Animal Science James R. Gillespie DelMar Publish 1998 AGRI CTE791 10 - 12 2003 B 2972 0-8273-7779-7 Companion Animals: Their Biology, Care, Health K & J Campbell Pearson/Prentice Hall 2009 AGRI CTE983 11 - 12 2009 B 3210 10:0-13-504767-6 and Management Encyclopedia of American Cat Breeds Meredith D. Wilson Tfh Publication Inc. 1978 AGRI 9 - 12 1991 B 2527 From Vines to Wines Jeff Cox Storey 1999 AGRI 9 - 12 2001 B 2854 Introduction to Agriculture Business Cliff Ricketts/Omri Rawlins DelMar Publish 2001 AGRI CTE763 10 - 12 2003 B 2942 0-7668-0024-5 Introduction to Landscaping Ronald J. Biondo/Charles B. Schroe Interstate 2000 AGRI 9 - 12 2001 B 2855 Introduction to Livestock and Companion, An Jasper Silee Interstate 1996 AGRI 9 - 12 2000 B 2802 Introduction to Veterinary Science Lawhead and Baker Thomson Deimar Learning 2005 AGRI CTE967/CTE968 10 - 12 2006 B 3137 076683302X Laboratory Investigations Jean Dickey Benjamin Cummings 2003 AGRI CTE808 10 - 12 2009 S 3215 0-8053-6789-6 Modern Biology Postlethwait/Hopson Holt, Rinehart, Winston 2007 AGRI CTE808 10 - 12 2009 B 3209 0-03-092215-1 Plants and Animals: Biology and Production Lee, Biondo, Hutter, Westrom, Pearson/Prentice Hall 2004 AGRI AG673/CTE401/ 10 - 12 2005 B 3112 0-13-036402-9 Patrick Interstate CTE761 Science of Agriculture, The Ray V.