The Success Behind the Candy-Colored Covers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Infatuation: Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts. the Case of Harlequin Enterprises and Sweden

GlobalGlobal Infatuation InfatuationExplorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts the case of harlequin enterprises and sweden HemmungsEvaEva Hemmungs Wirtén Wirtén Skrifter utgivna av Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala Publications from the Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University Nr 38 Global Infatuation Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts the case of harlequin enterprises and sweden Eva Hemmungs Wirtén Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University Uppsala 1998 Till Mamma och minnet av Pappa Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in literature presented at Uppsala University in 1998 Abstract Hemmungs Wirtén, E. 1998: Global Infatuation: Explorations in Transnational Publishing and Texts. The Case of Harlequin Enterprises and Sweden. Skrifter utgivna av Avdelningen för litteratursociologi vid Litteraturvetenskapliga institutionen i Uppsala. Publications from the Section for Sociology of Literature at the Department of Literature, Uppsala University, 38. 272 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-85178-28-4. English text. This dissertation deals with the Canadian category publisher Harlequin Enterprises. Operating in a hundred markets and publishing in twenty-four languages around the world, Harlequin Enterprises exempliıes the increasingly transnational character of publishing and the media. This book takes the Stockholm-based Scandinavian subsidiary Förlaget Harlequin as a case-study to analyze the complexities involved in the transposition of Harlequin romances from one cultural context into another. Using a combination of theoretical and empirical approaches it is argued that the local process of translation and editing – here referred to as transediting – has a fundamental impact on how the global book becomes local. -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

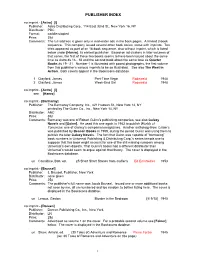

Publisher Index

PUBLISHER INDEX no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] Publisher: Astro Distributing Corp., 114 East 32nd St., New York 16, NY Distributor: PDC Format: saddle-stapled Price: 35¢ Comments: The full address is given only in mail-order ads in the back pages. A limited 2-book sequence. This company issued several other book series, some with imprints. Ten titles appeared as part of an 18-book sequence, also without imprint, which is listed below under [Hanro], its earliest publisher. Based on ad clusters in later volumes of that series, the first of these two books seems to have been issued about the same time as Astro #s 16 - 18 and the second book about the same time as Quarter Books #s 19 - 21. Number 1 is illustrated with posed photographs, the first volume from this publisher’s various imprints to be so illustrated. See also The West in Action. Both covers appear in the Bookscans database. 1 Clayford, James Part-Time Virgin Rodewald 1948 2 Clayford, James W eek -End Girl Rodewald 1948 no imprint - [ A s t r o ] [I] see [Hanro] no imprint - [Barmaray] Publisher: The Barmaray Company, Inc., 421 Hudson St., New York 14, NY printed by The Guinn Co., Inc., New York 14, NY Distributor: ANC Price: 35¢ Comments: Barmaray was one of Robert Guinn’s publishing companies; see also Galaxy Novels and [Guinn]. He used this one again in 1963 to publish Worlds of Tomorrow, one of Galaxy’s companion magazines. Another anthology from Collier’ s was published by Beacon Books in 1959, during the period Guinn was using them to publish the later Galaxy Novels. -

Care Needs of Women: Tending His Flock

#110: Care Needs of Women: Tending His Flock Recommended by the Writer: Abuse 1. Allender, Dr. Dan B. The Wounded Heart: Hope for Adult victims of Childhood Sexual Abuse . Colorado Springs: NavPress,1995, 2. Evans, Patricia. The Verbally Abusive Relationship . Avon: Adams Media Corporation, 1996. 3. Feldmeth, J.R. & M. Finley. We Weep for Ourselves and Our Children: A Christian Guide for Survivors of Childhood Sexual Abuse . San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990. 4. Heitritter, Lynn & Jeanette Vought. Helping Victims of Sexual Abuse: A Sensitive Biblical Guide for Counselors, Victims, and Families. Minneapolis: Bethany House, 2006. 5. Pillari, V. Scapegoating in Families: Intergenerational Patterns of Physical and Emotional Abuse . New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1991. Christian Caregiving 1. Collins, Gary R. How To Be a People Helper . Carol Springs: Tyndale House Publisher, Inc., 1995. 2. Haugk, Kenneth C. Christian Caregiving. Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1984. Depression 1. Biebel, David B. D. Min. & Harold G. Koenig, M.D. New Light on Depression: Help, Hope, and Answers for the Depressed & Those Who Love Them. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004. 2. Poinsett, Brenda. When the Saints Sing the Blues: Understanding Depression through the Lives of Job, Naomi, Paul, and Others . Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2006. Divorce 1. Carter, Les, Ph.D. Grace and Divorce . San Francisco: Jossey-B ass, 2005. 2. Smoke, Jim. Growing Through Divorce . Irving: Harvest House, 1976. Eating Disorders 1. Minirth, Dr. Frank, Dr. Paul Meier, Dr. Robert Hemfelt, Dr. Sharon Sneed, and Don Hawkins. Love Hunger: Recovery from Food Addiction . New York: Fawcett Columbine, 1990. 2. Vredevelt, Pam, Dr. Deborah Newman, Harry Beverly & Dr. -

Book Expo America History Will Be Kind to Me, for I Intend to Write It

june-july History is in the details By Brian Thornton Book Expo America History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it. - Winston Churchill Let me tell you, having read both Churchill’s memoirs and some of the “history” he wrote, the guy wasn’t kidding about history written by him being kind to him. And while Churchill’s fictionalization of history was equal parts intentional and unintentional, there is a growing group of authors who intentionally blend not only history and fiction, but history and crime. These writers of “historical mysteries” include such literary lights as Steven Saylor, Anne Perry, Jacqueline Winspear, Jason Goodwin, Steve Hockensmith and Louis Bayard (the first two are past Edgar Award winners, Winspear is a 2004 Edgar nominee and the last three are 2007 Edgar nominees). Whereas research has always played a large role in mystery writing, historical research can be a different animal altogether. I recently asked several historical mystery writers to name their favorite internet research tool, the one that most readily accomplished the twin goal of saving them time and giving them a maximum return on their investment. Hockensmith (Holmes on the Range, On the Wrong Track) Chuck Zito and Bill Bryan greet their fans. (Photos by Margery Flax) points to an overlooked sector of internet research: Yahoo groups. “For my latest book, I needed a ton of material on trains and railroad lines of the 1890s,” he says. After checking “literally dozens of train books” out of the library, Hockensmith still wasn’t getting what he needed, so he joined several Yahoo groups that catered to railroad enthusiasts and hit pay dirt. -

Slavery and Human Trafficking Statement for Financial Year2018

Slavery And Human Trafficking Statement For Financial Year 2018 This statement sets out the steps that we, News Corp, have taken across the News Corp Group to ensure that slavery or human trafficking is not taking place in any part of our own business or supply chains. This statement relates to actions and activities during the financial year 2018, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018. STATEMENT FROM CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER News Corp recognizes the importance of combating slavery and human trafficking, a crime that affects communities and individuals across the globe. We endorse a purposeful mission to improve the lives of others, as well as a passionate commitment to opportunity for all. As such, we are totally opposed to such abuses of a person’s freedoms both in our direct operations, our indirect operations and our supply chains. We are proud of the business standards News Corp upholds, as set out in the News Corp Standards of Business Conduct (the News Corp SOBC), see http://newscorp.com/corporate- governance/standards-of-business-conduct/) and are proud of the steps we have taken, and are committed to build upon, to ensure that slavery and human trafficking have no place either in our own business or our supply chains. Robert Thomson CEO, News Corp MEANING OF SLAVERY AND HUMAN TRAFFICKING For the purposes of this statement, slavery and human trafficking is based on the definitions set out in the Modern Slavery Act 2015 (the Act). We recognize that slavery and human trafficking can occur in many forms, such as forced labor, child labor, domestic servitude, sex trafficking and workplace abuse and it can include the restriction of a person’s freedom of movement whether that be physical, non-physical or, for example, by the withholding of a worker’s identity papers. -

Page 1 NAPA VALLEY UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT - INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS ADOPTION LIST

NAPA VALLEY UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT - INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS ADOPTION LIST SUBJECT TITLE AUTHOR PUBLISHER CR SUBJECT COURSE # GRADE AD CODE BK ISBN # ID# AGRICULTURE Agriculture Mechanics Fundamentals Ray V. Herren/Elmer L. Cooper DelMar Publish 2002 AGRI CTE770 9 - 12 2003 B 2943 0-7668-1410-6 Agriscience Fundamentals and Applications Elmer Cooper DelMar Publish 1997 AGRI 9 - 12 1997 B 2716 Animal Science James R. Gillespie DelMar Publish 1998 AGRI CTE791 10 - 12 2003 B 2972 0-8273-7779-7 Companion Animals: Their Biology, Care, Health K & J Campbell Pearson/Prentice Hall 2009 AGRI CTE983 11 - 12 2009 B 3210 10:0-13-504767-6 and Management Encyclopedia of American Cat Breeds Meredith D. Wilson Tfh Publication Inc. 1978 AGRI 9 - 12 1991 B 2527 From Vines to Wines Jeff Cox Storey 1999 AGRI 9 - 12 2001 B 2854 Introduction to Agriculture Business Cliff Ricketts/Omri Rawlins DelMar Publish 2001 AGRI CTE763 10 - 12 2003 B 2942 0-7668-0024-5 Introduction to Landscaping Ronald J. Biondo/Charles B. Schroe Interstate 2000 AGRI 9 - 12 2001 B 2855 Introduction to Livestock and Companion, An Jasper Silee Interstate 1996 AGRI 9 - 12 2000 B 2802 Introduction to Veterinary Science Lawhead and Baker Thomson Deimar Learning 2005 AGRI CTE967/CTE968 10 - 12 2006 B 3137 076683302X Laboratory Investigations Jean Dickey Benjamin Cummings 2003 AGRI CTE808 10 - 12 2009 S 3215 0-8053-6789-6 Modern Biology Postlethwait/Hopson Holt, Rinehart, Winston 2007 AGRI CTE808 10 - 12 2009 B 3209 0-03-092215-1 Plants and Animals: Biology and Production Lee, Biondo, Hutter, Westrom, Pearson/Prentice Hall 2004 AGRI AG673/CTE401/ 10 - 12 2005 B 3112 0-13-036402-9 Patrick Interstate CTE761 Science of Agriculture, The Ray V. -

1. I Occasionally Use the Term “Romance Novel” Interchangeably with “Genre Romance” and “Romance Fiction.” 2

Notes Preface 1. I occasionally use the term “romance novel” interchangeably with “genre romance” and “romance fiction.” 2. In The Theory of the Novel, Georg Lukács suggests that forms of art are burdened with the task of dealing with the loss of a sense of completeness, a loss that results from our fragmented reality under modernity (38). Introduction: What Does It Mean to Say “Romance Novel”? 1. Regis’s chapter “The Definition” recounts how the terms romance and novel have been used in the past and then turns to listing the eight elements that she considers “essential” to a romance novel (19–25). 2. Audio books have become an increasingly popular medium for romance novels but this is only a transposition of the narrative voice, without any significant ontological change. The narra- tor recites the prose that the reader might have read aloud or silently. 3. For more on Lifetime’s ascendance over the nineties, see Lifetime: A Cable Network “For Women.” 4. Amanda D. Lotz, in her analysis of the Lifetime series Any Day Now, documents the extent to which networks like Lifetime influ- ence the writers of their media software. Lotz notes that not only did Lifetime insist on a significant change in the original script before agreeing to air the show, but its executives jostled with the show’s creators and producers regularly: Content that narrowed the potential audience (too focused on ethnicity issues, addressing women of certain age groups) and the series’ tone (“nice” women’s stories vs. “exploita- tion” themes) proved particularly contentious in the strug- gle over creative autonomy. -

Annual Report 2016 More Than 50% of Dow Jones Revenues Came from Digital N N N N N N

Annual Report 2016 More than 50% of Dow Jones revenues came from digital n n n n n n WSJ+ GETAWAY Win a Three-Night Stay at Enchantment Resort in Arizona* Nestled among the towering red rocks of Sedona, Arizona, Enchantment Resort n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n combines rugged grandeur with luxury and Native American culture. Enjoy stunning scenery and a wide array of activities, including golf at Seven Canyons. COMPETITION CLOSES AT MIDNIGHT ON OCTOBER 31, 2015 HarperCollins expanded ENTER NOW AT WSJPLUS.COM/SEDONA operations in Brazil, EXCLUSIVE TO SUBSCRIBERS France and Italy OFFERS / EXPERIENCES / GETAWAYS / TALKS *No purchase necessary. Void where prohibited. Open to subscribers as of October 2, 2015, 21 and over, who are legal residents of the 50 United States (or D.C.). For full offi cial rules visit wsjplus.com/offi cialrules. © 2015 Dow Jones & Co., Inc. All rights reserved. 6DJ2672 INT ROD UCING n n n n n n Mobile now accounts for ONLY THE EX CEPTIONAL more than 50% of realtor.com®’s overall traffic INT ROD UCING ONLY THE EX CEPTIONAL INT ROD UCING ONLY THE EX CEPTIONAL n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n The premier digital destination that connects your brand to the world’s most affluent property seekers featuring a unique selection of prestige properties, premium news, data and insights. mansionglobal.com For advertising opportunities, please contact [email protected] REA acquired iProperty, LAUNCH PARTNERS: Asia’s #1 onlineLAUNCH property PARTNERS: group LAUNCH PARTNERS: © 2015 Dow Jones & Co., Inc. -

HARPERCOLLINSPUBLISHERS FOREIGN RIGHTS GUIDE Harper

HARPERCOLLINSPUBLISHERS FOREIGN RIGHTS GUIDE Harper William Morrow Ecco Amistad Rayo HarperOne Collins Collins Living Collins Business Collins Design Smithsonian Books Avon HarperEntertainment Eos Harper Perennial Harper Paperbacks HarperStudio Frankfurt 2008 Brenda Segel Senior Vice President & Director Foreign & Domestic Rights Phone: (212) 207-7252 Fax: (212) 207-7902 [email protected] Juliette Shapland (JS) Director, Foreign Rights Ecco, Harper, William Morrow Phone: (212) 207-7504 [email protected] Sandy Hodgman (SH) Senior Manager, Foreign Rights Harper, Smithsonian Books, Collins, Collins Living Phone: (212) 207-6910 [email protected] Carolyn Bodkin (CB) Senior Manager, Foreign Rights Avon, HarperEntertainment, Eos, Harper Paperbacks, Rayo, Amistad, Harper Perennial Phone: (212) 207-7927 [email protected] Catherine Barbosa Ross (CBR) Manager, Foreign Rights HarperOne, Collins Business, Illustrated Books Phone: (212) 207-7231 [email protected] Please visit us on www.harpercollinsrights.com or email us at [email protected] for more information on other HarperCollins books 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS HARPER FICTION…………….…………………...…4 WILLIAM MORROW FICTION…….………………....15 BIOGRAPHY / MEMOIR…………………………......23 HARPER NON-FICTION…………...……………..….32 WILLIAM MORROW NON-FICTION…………..…..….45 BUSINESS.……….……………………………….…48 PSYCHOLOGY / SELF-HELP………..……………....54 HARPERONE……………………………...……......60 ILLUSTRATED……………….…………….………...72 COOKBOOKS……………………………….……….75 HARPERENTERTAINMENT………………….……….77 AVON………..……………………………….….…..79 *Indicates a new addition to the list since BEA 2008 3 HARPER FICTION Andrews, Mary Kay *THE FIXER UPPER New York Times bestselling author Mary Kay Andrews returns with a stand-alone novel about a woman whose professional fall from grace lands her back in a hometown she never knew, amongst a gothic Southern family she’s never met, and taking on a task she never imagined. -

Twentieth Century Paperbacks Collection MSS 219 3.5 Linear Feet

Twentieth Century Paperbacks Collection MSS 219 3.5 linear feet Background Writing in Hardboiled America: The Lurid Years of Paperbacks, Geoffrey O’Brien summarizes the rise of the modern American paperback book: Cheap reprints and books bound in paper arose and flourished sporadically in America from the nineteenth century onwards. Although most of these were purely commercial efforts, a significant percentage were associated with a zeal for bringing culture to the masses. Nevertheless, and despite the obvious practicality of cheap mass printing, no one had been able to give that kind of publishing any permanence until June 19th, 1939, when the first ten releases of Pocket Books saw the light of day. Robert DeGraff, the company’s founder, may have been influenced by the success of Penguin Books, which had begun publishing several years earlier in England (33). Commenting on the cover art, Mr. O’Brien wrote: What surprises in the end is how much of paperback art of the Forties and Fifties conveys a sense of reality and a warmth of emotion. Even the fantasies have a homespun texture, and the most unreal of them are brought down to earth, if only by the crudeness of their execution. Today’s spell-casters have more elaborate tools at their disposal for imparting a magical aura to the every more efficient packaging. The success story of the media has culminated in a kind of computerized aesthetics not programmed for loose ends, in which considerations like corporate image and demographics are part of every image. When the bright lights and synthesized soundtracks of today’s conglomerate marketing merge into a single vast blur, it is comforting to rest a while in the clear lines of the ramshackle porch on the cover of Erskine Caldwell’s Journeyman, or to sit with Studs Lonigan in the park on a warm summer night. -

Special Topics in Collegiate Ministry CECM 6392 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Division of Church Ministry Summer 2021, Aug

Special Topics in Collegiate Ministry CECM 6392 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Division of Church Ministry Summer 2021, Aug. 3-6 (Collegiate Week) Beth Masters, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Collegiate Ministry (504) 289-7074 cell [email protected] Mission Statement: New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary and Leavell College prepare servants to walk with Christ, proclaim His truth, and fulfill His mission Course Description The purpose of this course to expose students to national training, interaction with peers and professionals, and to allow students to network for future options within college ministry. This course will encourage students to interview and spend time with current professionals in collegiate settings across the world to learn and grow from their experiences. Additionally, allowing students to interact with texts that will challenge them and prepare them to serve in a collegiate setting as a volunteer, staff member, or lead college minister. Core Value Focus The seminary has five core values. Doctrinal Integrity: Knowing that the Bible is the Word of God, we believe it, teach it, proclaim it, and submit to it. This course addresses Doctrinal Integrity specifically by preparing students to grow in understanding and interpreting of the Bible. Spiritual Vitality: We are a worshiping community emphasizing both personal spirituality and gathering together as a Seminary family for the praise and adoration of God and instruction in His Word. Spiritual Vitality is addressed by reminding students that a dynamic relationship with God is vital for effective ministry. Mission Focus: We are not here merely to get an education or to give one. We are here to change the world by fulfilling the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries.