Ecology and Behavior of First Instar Larval Lepidoptera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fung Yuen SSSI & Butterfly Reserve Moth Survey 2009

Fung Yuen SSSI & Butterfly Reserve Moth Survey 2009 Fauna Conservation Department Kadoorie Farm & Botanic Garden 29 June 2010 Kadoorie Farm and Botanic Garden Publication Series: No 6 Fung Yuen SSSI & Butterfly Reserve moth survey 2009 Fung Yuen SSSI & Butterfly Reserve Moth Survey 2009 Executive Summary The objective of this survey was to generate a moth species list for the Butterfly Reserve and Site of Special Scientific Interest [SSSI] at Fung Yuen, Tai Po, Hong Kong. The survey came about following a request from Tai Po Environmental Association. Recording, using ultraviolet light sources and live traps in four sub-sites, took place on the evenings of 24 April and 16 October 2009. In total, 825 moths representing 352 species were recorded. Of the species recorded, 3 meet IUCN Red List criteria for threatened species in one of the three main categories “Critically Endangered” (one species), “Endangered” (one species) and “Vulnerable” (one species” and a further 13 species meet “Near Threatened” criteria. Twelve of the species recorded are currently only known from Hong Kong, all are within one of the four IUCN threatened or near threatened categories listed. Seven species are recorded from Hong Kong for the first time. The moth assemblages recorded are typical of human disturbed forest, feng shui woods and orchards, with a relatively low Geometridae component, and includes a small number of species normally associated with agriculture and open habitats that were found in the SSSI site. Comparisons showed that each sub-site had a substantially different assemblage of species, thus the site as a whole should retain the mosaic of micro-habitats in order to maintain the high moth species richness observed. -

Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus Occidentalis) Recovery Plan

Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis) Recovery Plan Wildlife Management Program No. 58 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife October 2014 Wildlife Management Program No. 58 Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis) Recovery Plan October 2014 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983 Foreword Recovery plans are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Parks and Wildlife Policy Statements Nos. 44 and 50 (CALM 1992, 1994), and the Australian Government Department of the Environment’s Recovery Planning Compliance Checklist for Legislative and Process Requirements (DEWHA 2008). Recovery plans outline the recovery actions that are needed to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. Recovery plans are a partnership between the Department of the Environment and the Department of Parks and Wildlife. The Department of Parks and Wildlife acknowledges the role of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and the Department of the Environment in guiding the implementation of this recovery plan. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds necessary to implement actions are subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. This recovery plan was approved by the Department of Parks and Wildlife, Western Australia. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in status of the taxon or ecological community, and the completion of recovery actions. Information in this recovery plan was accurate as of October 2014. -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Making a Meeting Place Eucalypt Trail Map and Signs

Friends of the Australian National Botanic Gardens Number 73 April 2013 Inside: Making a Meeting Place Eucalypt Trail map and signs Friends of the Australian National Botanic Gardens Patron His Excellency Mr Michael Bryce AM AE Vice Patron Mrs Marlena Jeffery President David Coutts Vice President Barbara Podger Secretary John Connolly Treasurer Marion Jones Public Officer David Coutts General Committee Dennis Ayliffe Glenys Bishop Anne Campbell Lesley Jackman Warwick Wright Talks Convenor Lesley Jackman Membership Secretary Barbara Scott Fronds Committee Margaret Clarke Barbara Podger Anne Rawson Growing Friends Kath Holtzapffel Botanic Art Groups Helen Hinton Photographic Group Graham Brown Social events Jan Finley Exec. Director, ANBG Dr Judy West Post: Friends of ANBG, GPO Box 1777 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Telephone: (02) 6250 9548 (messages) Internet: www.friendsanbg.org.au Email addresses: [email protected] IN THIS ISSUE [email protected] [email protected] Eucalypt Trail map and signs.................................................2 Fronds is published three times a year. We welcome your articles for inclusion in the next Discover eucalypts ................................................................3 issue. Material should be forwarded to the Giant wood moths in the Gardens .........................................4 Fronds Committee by mid-February for the April issue; mid-June for the August issue; Growing Friends ....................................................................6 mid-October -

Report October 2017

Defoliation of jarrah in the Leeuwin-Naturaliste region of Western Australia September-October 2017 Version: 1.1 Approved by: Last Updated: 6 October 2017 Custodian: Allan J. Wills Review date: October 2018 Version Date approved Approved by Brief Description number DD/MM/YYYY 1.1 Defoliation of jarrah in the Leeuwin- Naturaliste region of Western Australia September-October 2017 Allan J. Wills and Janet D. Farr Occasional report October 2017 Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 Phone: (08) 9219 9000 Fax: (08) 9334 0498 www.dbca.wa.gov.au © Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions on behalf of the State of Western Australia 2017 October 2017 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. This report was prepared by Allan J. Wills and Janet D. Farr Questions regarding the use of this material should be directed to: Allan J. Wills Senior Technical Officer Science and Conservation Division Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983 Phone: 0438996352 Email: [email protected] The recommended reference for this publication is: Wills AJ & Farr JD (2017). Defoliation of jarrah in the Leeuwin-Naturaliste region of Western Australia September-October 2017. Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Perth. -

Cross-Crop Resistance of Spodoptera Frugiperda Selected on Bt Maize To

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Cross‑crop resistance of Spodoptera frugiperda selected on Bt maize to genetically‑modifed soybean expressing Cry1Ac and Cry1F proteins in Brazil Eduardo P. Machado1, Gerson L. dos S. Rodrigues Junior1, Fábio M. Führ1, Stefan L. Zago1, Luiz H. Marques2*, Antonio C. Santos2, Timothy Nowatzki3, Mark L. Dahmer3, Celso Omoto4 & Oderlei Bernardi1* Spodoptera frugiperda is one of the main pests of maize and cotton in Brazil and has increased its occurrence on soybean. Field‑evolved resistance of this species to Cry1 Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) proteins expressed in maize has been characterized in Brazil, Argentina, Puerto Rico and southeastern U.S. Here, we conducted studies to evaluate the survival and development of S. frugiperda strains that are susceptible, selected for resistance to Bt‑maize single (Cry1F) or pyramided (Cry1F/Cry1A.105/ Cry2Ab2) events and F 1 hybrids of the selected and susceptible strains (heterozygotes) on DAS‑ 444Ø6‑6 × DAS‑81419‑2 soybean with tolerance to 2,4‑d, glyphosate and ammonium glufosinate herbicides (event DAS‑444Ø6‑6) and insect‑resistant due to expression of Cry1Ac and Cry1F Bt proteins (event DAS‑81419‑2). Susceptible insects of S. frugiperda did not survive on Cry1Ac/Cry1F‑ soybean. However, homozygous‑resistant and heterozygous insects were able to survive and emerge as fertile adults when fed on Cry1Ac/Cry1F‑soybean, suggesting that the resistance is partially recessive. Life history studies revealed that homozygous‑resistant insects had similar development, reproductive performance, net reproductive rate, intrinsic and fnite rates of population increase on Cry1Ac/Cry1F‑soybean and non‑Bt soybean. In contrast, heterozygotes had their fertility life table parameters signifcantly reduced on Cry1Ac/Cry1F‑soybean. -

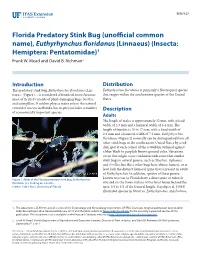

Florida Predatory Stink Bug (Unofficial Common Name), Euthyrhynchus Floridanus(Linnaeus) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)1 Frank W

EENY157 Florida Predatory Stink Bug (unofficial common name), Euthyrhynchus floridanus (Linnaeus) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)1 Frank W. Mead and David B. Richman2 Introduction Distribution The predatory stink bug, Euthyrhynchus floridanus (Lin- Euthyrhynchus floridanus is primarily a Neotropical species naeus) (Figure 1), is considered a beneficial insect because that ranges within the southeastern quarter of the United most of its prey consists of plant-damaging bugs, beetles, States. and caterpillars. It seldom plays a major role in the natural control of insects in Florida, but its prey includes a number Description of economically important species. Adults The length of males is approximately 12 mm, with a head width of 2.3 mm and a humeral width of 6.4 mm. The length of females is 12 to 17 mm, with a head width of 2.4 mm and a humeral width of 7.2 mm. Euthyrhynchus floridanus (Figure 2) normally can be distinguished from all other stink bugs in the southeastern United States by a red- dish spot at each corner of the scutellum outlined against a blue-black to purplish-brown ground color. Variations occur that might cause confusion with somewhat similar stink bugs in several genera, such as Stiretrus, Oplomus, and Perillus, but these other bugs have obtuse humeri, or at least lack the distinct humeral spine that is present in adults of Euthyrhynchus. In addition, species of these genera Figure 1. Adult of the Florida predatory stink bug, Euthyrhynchus known to occur in Florida have a short spine or tubercle floridanus (L.), feeding on a beetle. situated on the lower surface of the front femur behind the Credits: Lyle J. -

Variably Hungry Caterpillars: Predictive Models and Foliar Chemistry Suggest How to Eat a Rainforest

Downloaded from http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on November 9, 2017 Variably hungry caterpillars: predictive rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org models and foliar chemistry suggest how to eat a rainforest Simon T. Segar1,2, Martin Volf1,2, Brus Isua3, Mentap Sisol3, Research Conor M. Redmond1,2, Margaret E. Rosati4, Bradley Gewa3, Kenneth Molem3, Cite this article: Segar ST et al. 2017 Chris Dahl1,2, Jeremy D. Holloway5, Yves Basset1,2,6, Scott E. Miller4, Variably hungry caterpillars: predictive models George D. Weiblen7, Juha-Pekka Salminen8 and Vojtech Novotny1,2 and foliar chemistry suggest how to eat a rainforest. Proc. R. Soc. B 284: 20171803. 1Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia in Ceske Budejovice, Branisovska 1760, 37005 Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1803 2Biology Centre, The Czech Academy of Sciences, Branisovska 31, 37005 Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic 3New Guinea Binatang Research Center, PO Box 604 Madang, Madang, Papua New Guinea 4National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA 5Department of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK Received: 11 August 2017 6Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 0843-03092, Panama City, Republic of Panama Accepted: 9 October 2017 7Bell Museum of Natural History and Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of Minnesota, 1479 Gortner Avenue, Saint Paul, MN 55108-1095, USA 8Department of Chemistry, University of Turku, Vatselankatu 2, FI-20500 Turku, Finland STS, 0000-0001-6621-9409; MV, 0000-0003-4126-3897; YB, 0000-0002-1942-5717; SEM, 0000-0002-4138-1378; GDW, 0000-0002-8720-4887; J-PS, 0000-0002-2912-7094; Subject Category: VN, 0000-0001-7918-8023 Ecology A long-term goal in evolutionary ecology is to explain the incredible diversity Subject Areas: of insect herbivores and patterns of host plant use in speciose groups like ecology, evolution tropical Lepidoptera. -

The Mcguire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity

Supplemental Information All specimens used within this study are housed in: the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity (MGCL) at the Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville, USA (FLMNH); the University of Maryland, College Park, USA (UMD); the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, France (MNHN); and the Australian National Insect Collection in Canberra, Australia (ANIC). Methods DNA extraction protocol of dried museum specimens (detailed instructions) Prior to tissue sampling, dried (pinned or papered) specimens were assigned MGCL barcodes, photographed, and their labels digitized. Abdomens were then removed using sterile forceps, cleaned with 100% ethanol between each sample, and the remaining specimens were returned to their respective trays within the MGCL collections. Abdomens were placed in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes with the apex of the abdomen in the conical end of the tube. For larger abdomens, 5 mL microcentrifuge tubes or larger were utilized. A solution of proteinase K (Qiagen Cat #19133) and genomic lysis buffer (OmniPrep Genomic DNA Extraction Kit) in a 1:50 ratio was added to each abdomen containing tube, sufficient to cover the abdomen (typically either 300 µL or 500 µL) - similar to the concept used in Hundsdoerfer & Kitching (1). Ratios of 1:10 and 1:25 were utilized for low quality or rare specimens. Low quality specimens were defined as having little visible tissue inside of the abdomen, mold/fungi growth, or smell of bacterial decay. Samples were incubated overnight (12-18 hours) in a dry air oven at 56°C. Importantly, we also adjusted the ratio depending on the tissue type, i.e., increasing the ratio for particularly large or egg-containing abdomens. -

Appendix 5.3 MON 810 Literature Review – List of All Hits (June 2016

Appendix 5.3 MON 810 literature review – List of all hits (June 2016-May 2017) -Web of ScienceTM Core Collection database 12/8/2016 Web of Science [v.5.23] Export Transfer Service Web of Science™ Page 1 (Records 1 50) [ 1 ] Record 1 of 50 Title: Ground beetle acquisition of Cry1Ab from plant and residuebased food webs Author(s): Andow, DA (Andow, D. A.); Zwahlen, C (Zwahlen, C.) Source: BIOLOGICAL CONTROL Volume: 103 Pages: 204209 DOI: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.09.009 Published: DEC 2016 Abstract: Ground beetles are significant predators in agricultural habitats. While many studies have characterized effects of Bt maize on various carabid species, few have examined the potential acquisition of Cry toxins from live plants versus plant residue. In this study, we examined how live Bt maize and Bt maize residue affect acquisition of Cry1Ab in six species. Adult beetles were collected live from fields with either currentyear Bt maize, oneyearold Bt maize residue, twoyearold Bt maize residue, or fields without any Bt crops or residue for the past two years, and specimens were analyzed using ELISA. Observed Cry1Ab concentrations in the beetles were similar to that reported in previously published studies. Only one specimen of Cyclotrachelus iowensis acquired Cry1Ab from twoyearold maize residue. Three species acquired Cry1Ab from fields with either live plants or plant residue (Cyclotrachelus iowensis, Poecilus lucublandus, Poecilus chalcites), implying participation in both liveplant and residuebased food webs. Two species acquired toxin from fields with live plants, but not from fields with residue (Bembidion quadrimaculatum, Elaphropus incurvus), suggesting participation only in live plantbased food webs. -

In Vitro Propagation of Eucalyptus Spec1es•

McComb, J.A., Bennett, I.J. and Tonkin, C. (1996) In vitro propagation of Eucalyptus species. In: Taji, A. and Williams, R., (eds.) Tissue culture of Australian plants. University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia, pp. 112-156 Chapter 4 In vitro propagation of Eucalyptus spec1es• 2 1 J.A. McComb1, I.J. Bennett and C. Tonkin 1 School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Murdoch University, Murdoch, WA 6150. 2 school of Applied Science, Edith Cowan University, Mount Lawley, WA 6050 Australia. Contents • Introduction • Two case studies of the application of tissue culture • Eucalypts important in plantations • Tissue culture of other species of eucalypts • Conclusion KEY WORDS: Eucalyptus, eucalypt, micropropagation, clonal field trials, Phytophthora cinnamomi, root architecture, in vitro rooting, salt tolerance, transformation, protoplasts. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS: AFOCEL Association Foret Cellulose BAP Benzy!amino-purine BT Bacillus thuringensis CSIRO Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation GA3 Gibberellin A3 IAA Indole acetic acid IBA Indole butyric acid MS Murashige and Skoog (1962) medium NAA Naphthalene acetic acid RR Resistant jarrah seedlings from families on average, resistant to dieback RS Resistant jarrah seedlings from families on average, susceptible to dieback ss Susceptible jarrah seedlings from families on average, susceptible to die back LIST OF SPECIES (see end of chapter). 112 In vitro propagation of Eucalyptus species Introduction The importance of eucalypts and reasons for tissue culture Eucalypts are Australia's most distinctive plant group. They are contained within the genus Eucalyptus which consists of over 500 named species, with more as yet unnamed (Brooker & Kleinig 1983; 1990 Chippendale 1988). The natural distribution of the genus is almost completely confined to the Australian continent and Tasmania with only two species, E. -

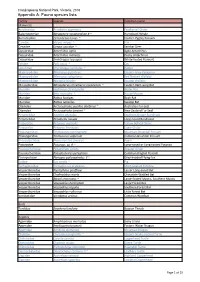

Report-VIC-Croajingolong National Park-Appendix A

Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, 2016 Appendix A: Fauna species lists Family Species Common name Mammals Acrobatidae Acrobates pygmaeus Feathertail Glider Balaenopteriae Megaptera novaeangliae # ~ Humpback Whale Burramyidae Cercartetus nanus ~ Eastern Pygmy Possum Canidae Vulpes vulpes ^ Fox Cervidae Cervus unicolor ^ Sambar Deer Dasyuridae Antechinus agilis Agile Antechinus Dasyuridae Antechinus mimetes Dusky Antechinus Dasyuridae Sminthopsis leucopus White-footed Dunnart Felidae Felis catus ^ Cat Leporidae Oryctolagus cuniculus ^ Rabbit Macropodidae Macropus giganteus Eastern Grey Kangaroo Macropodidae Macropus rufogriseus Red Necked Wallaby Macropodidae Wallabia bicolor Swamp Wallaby Miniopteridae Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis ~ Eastern Bent-wing Bat Muridae Hydromys chrysogaster Water Rat Muridae Mus musculus ^ House Mouse Muridae Rattus fuscipes Bush Rat Muridae Rattus lutreolus Swamp Rat Otariidae Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus ~ Australian Fur-seal Otariidae Arctocephalus forsteri ~ New Zealand Fur Seal Peramelidae Isoodon obesulus Southern Brown Bandicoot Peramelidae Perameles nasuta Long-nosed Bandicoot Petauridae Petaurus australis Yellow Bellied Glider Petauridae Petaurus breviceps Sugar Glider Phalangeridae Trichosurus cunninghami Mountain Brushtail Possum Phalangeridae Trichosurus vulpecula Common Brushtail Possum Phascolarctidae Phascolarctos cinereus Koala Potoroidae Potorous sp. # ~ Long-nosed or Long-footed Potoroo Pseudocheiridae Petauroides volans Greater Glider Pseudocheiridae Pseudocheirus peregrinus