Two Common Errors About the Proportions of the ‛Ūd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MGS Guitarist Sept/Oct

A Publication of the Minnesota Guitar Society • P.O. Box 14986 • Minneapolis, MN 55414 SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2007 VOL. 23 NO. 5 SundinSundin HallHall ConcertsConcerts AnAn ExcitingExciting NewNew SeasonSeason Begins!Begins! Lucas Harris baroque lute Saturday September Berta Rojas classical guitar Saturday October Also In This Issue News and Notes about OpenStage Local Artists concerts and more Minnesota Guitar Society Board of Directors Newsletter EDITOR OFFICERS: BOARD MEMBERS: Paul Hintz PRESIDENT Joe Haus Steve Kakos PRODUCTION Alan Norton VICE-PRESIDENT Joanne Backer i draw the line, inc. Annett Richter ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Joe Hagedorn David’s Print Shop Daniel Sturm DISTRIBUTION TREASURER Jim Campbell Kuan Teoh Todd Tipton MANAGING DIRECTOR Paul Hintz Todd Tipton Web Site Production SECRETARY Patrick Strother Brent Weaver Amy Lytton <http://www.mnguitar.org> Minnesota Guitar Society The Minnesota Guitar Society concert season is co-sponsored by Mission Statement Sundin Hall. This activity is made To promote the guitar, in all its stylistic and cultural diversity, possible in part by a grant from the through our newsletter and through our sponsorship of Minnesota State Arts Board, through public forums, concerts, and workshops. an appropriation by the Minnesota State Legislature and a grant from To commission new music and to aid in its the National Endowment for the promotion, publication, and recording. Arts. Matching funds have been To serve as an educational and social link between amateur and provided by General Mills, AT&T, professional guitarists and the community. and Ameriprise Financial. To promote and help create opportunities for Minnesota guitarists and players of related instruments. To reserve tickets for any Sundin Hall concert, call our phone line at 612-677-1151 and leave a message. -

Pasqualini Demarzi Six Sonatas for Cetra Or Kitara

Pasqualini Demarzi Six Sonatas for Cetra or Kitara Doc Rossi, 18th-century Cittern Andrea Damiani, Archlute and Baroque Guitar Doc Rossi & Andrea Damiani The Instruments The cittern seems to have started life as a conscious attempt at refashioning the Classical Greek “kithara” Sonata I: Sostenuto, Aria, Minuet to Italian Renaissance taste. The Renaissance cittern had a very shallow body, tapering from the neck (4.5-6cm) to the base (2-2.5cm) and, for the most part, used a re-entrant tuning that was well-suited to The Musical Priest (trad. arr. Rossi) playing with a plectrum, and to chording. Instruments typically had from 4 to 6 courses, double- and/or triple strung, sometimes with octaves, sometimes all unisons. Arch-citterns with up to 8 extra basses also Sonata II: Moderato, Largo, Allegro, Minuet existed. Typical fingerboard string lengths were from 44cm to 60cm, although several scholars believe that a much shorter instrument also existed, more suitable for the small but demanding solo repertoire. The Rights of Man (trad. arr. Rossi) String length has a distinctive though subtle effect on sound that is easier to hear than to describe – given the same pitch, similar string tension and double-strung courses, a longer string length is somewhat Sonata III: Moderato, Largo, Grazioso softer, with a characteristic “whoosh” during position changes that can be heard on today’s Appalachian dulcimer. The re-entrant tuning necessitates almost constant position changing when playing melodies of The Fairy Hornpipe - Whisky You're the Devil (trad. arr. Rossi) any range. The combination of shallow body and longer string length gives the Renaissance cittern a bright, jangling sound, which is further emphasized when it is played with a plectrum. -

Recorder Music Marcello · Vivaldi · Bellinzani

Recorder Music Marcello · Vivaldi · Bellinzani Manuel Staropoli recorder · Gioele Gusberti cello · Paolo Monetti double bass Pietro Prosser archlute, Baroque guitar · Manuel Tomadin harpsichord, organ Recorder Music Benedetto Marcello 1686–1739 Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Paolo Benedetto Bellinzani Sonata No.12 in F Concerto in D minor Sonata No.12 in D minor for flute and b.c. arranged for flute and cembalo obligato for flute and b.c. 1. Adagio 3’03 14. Allegro 3’25 25. Largo 2’02 2. Minuet. Allegro 0’51 15. Largo 3’25 26. (Allegro) 1’59 3. Gavotta. Allegro 0’54 16. Allegro 3’32 27. Cembalo only for breath 4. Largo 1’04 of the Flute 1’16 5. Ciaccona. Allegro 3’51 Paolo Benedetto Bellinzani 28. Follia 8’14 Sonata No.10 in F Paolo Benedetto Bellinzani for flute and b.c. c.1690–1757 17. Adaggio 3’58 Sonata No.7 in G minor 18. Presto 2’12 for flute and b.c. 19. Adaggio 1’08 Manuel Staropoli recorder 6. Largo 1’52 20. (Gavotta) 1’57 Gioele Gusberti cello 7. Presto 1’50 Paolo Monetti double bass 8. Largo 1’43 Benedetto Marcello Pietro Prosser archlute, Baroque guitar 9. Giga (without tempo indication) 1’37 Sonata No.8 in D minor Manuel Tomadin harpsichord, organ for flute and b.c. Benedetto Marcello 21. Adagio 3’09 Sonata No.6 in G 22. Allegro 2’30 for flute and b.c. 23. Largo 1’32 10. Adagio 3’35 24. Allegro 3’59 11. Allegro 3’13 12. Adagio 1’28 13. -

Fomrhi Q144.Pdf

Quarterly No. 144, December 2018 FoMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 144 Christopher Goodwin 2 COMMUNICATIONS 2099 Making woodwind instruments 11: Recorders Jan Bouterse 9 2100 Oboe collection of Han de Vries in Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Jan Bouterse 20 2101 In defence of real lutes and theorbos – why history matters Michael Lowe 21 2102 Turkish castanets, or should that be ‘bones’?, a correction to Comm 2094 Christopher Goodwin 31 2103 Reviews of two books by Christopher Page: The Guitar in Tudor England: A Social and Musical History (Cambridge University Press, 2015) [xix, 248 p. ISBN 9781107108363]; The Guitar in Stuart England: A Social and Musical History (Cambridge University Press, 2017) [xix, 288 p. ISBN 9781108419789] Martyn Hodgson 34 The next issue, Quarterly 145, will appear in March. Please send in Comms and announcements to the address below, to arrive by 1st March Fellowship of Makers and Researchers of Historical Instruments Committee: Andrew Atkinson, Peter Crossley, John Downing, Luke Emmet, Peter Forrester, Eleanor Froelich, Martyn Hodgson, Jim Lynham, Jeremy Montagu, Filadelfio Puglisi, Michael Roche, Alexander Rosenblatt, Marco Tiella, Secretary/Quarterly Editor: Christopher Goodwin Treasurer: John Reeve Webmaster: Luke Emmet Southside Cottage, Brook Hill, Albury, Guildford GU5 9DJ, Great Britain Tel: (++44)/(0)1483 202159 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.fomrhi.org BULLETIN 144 Christopher Goodwin This is the fourth and final issue of the 2018 subscription year (numbers 141-144), more or less on time and with a mix of workshop advice and provocative argument. Many thanks to the contributors. A few people have paid in advance for 2019, and I have written to them to tell them so; otherwise you will find herewith a subscription form to renew your subscription. -

PERFORMER ROLE CODES Role Code

PERFORMER ROLE CODES To help calculate the share of revenues that individual performers should receive from use of a sound recording, a performer is assigned a contributor category and role code. Role codes are split into a number of types – not all of which are eligible for payment. Each type is further sorted into different instrumental, vocal or studio personnel performances, so that it is easy to identify what each performer contributed to a sound recording. Payable roles are generally ones which provide an audible contribution to the final sound recording. Non-payable roles are generally studio activities which add no audible contribution to the final sound recording. PAYABLE ROLES There are a number of payable roles. These are broken down into groups depending on the activity or instrument being played. See below all of the roles within each group. BRASS Role Code Alphorn ALP Alto Horn ALH Alto Trombone ATR Alto Valve Trombone AVT Bankia BKA Bass Trombone BTR Bass Trumpet BTP Bass Tuba BTB Brass Bass BRB Bugle BUE Cornet CTO Corno Da Caccia CDC Dung-Chen DUN Euphonium EUP FanfareTrumpet FFT Flugelhorn FLH French Horn FRH Horn HRN Horn HOR Hunting Horn (Valved) HHN Piccolo Trumpet PCT Sackbut SCK Slide Trumpet STP Sousaphone SOU Tenor Horn TNH Trombone TRM Trompeta TOA Trumpet TRU Trumpet (Eflat) TEF Tuba TUB ValveTrombone VTR ELECTRONICS Role Code Barrel Organ BRO Barrel Piano BPN Beat Box BBX DJ D_J DJ (Scratcher) SCT Emulator EMU Fairground Organ FGO Hurdy Gurdy HUR Musical Box BOX Ondioline OND Optigan OPG Polyphon PPN Programmer -

Fomrhi Comm. 2101 Michael Lowe in Defence of Real Lutes And

FoMRHI Comm. 2101 Michael Lowe In defence of real lutes and theorbos—why history matters It is now more than fifty years since I built my first lute, and during that time we have learned a great deal about the instruments, their repertoire and the manner of playing them. Most of this advance in knowledge has come about through intense study of historical source material: the instruments themselves, the music itself, literature and iconography. Today, however, we have a crisis in the lute world. A significant number of professional lutenists has chosen to ignore many of the things which are known about historical instruments and the way of playing them, preferring instead to invent their own ways of doing things. This manifests itself most clearly when members of the lute family are employed as continuo instruments. Does this matter? Surely, so long as the person is playing on an instrument with a lute-shaped body and some sort of neck-extension, that is all that matters. Well, clearly, for a number of people that is, indeed, all that matters but, surely, this is not satisfactory. The lute had a very complicated history, not least because it was always being modified to suit particular musical requirements at various times and in various places. Those people who ignore historical practices are failing to understand these subtleties of the lute’s history and this lack of understanding often manifests itself in those players’ whole approach to the music. Let me quote from J. A. Scheibe in 1740. He was a composer and the Capellmeister in Brandenburg-Culm- -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

N O V E M B E R 2 0

Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLIV, No. 5 november 2003 A Flanders Recorder Quartet Guide for Recorder Players and Teachers BART SPANHOVE With a historical Chapter by DAVID LASOCKI The purpose of this book is to help recorder players become better ensemble members. Bart Spanhove has written the book in response to numerous requests from both amateurs and professionals to set down some practical suggestions based on his own experience and thereby fill a long-felt gap in the literature Alamire Music Publishers about the recorder. Toekomstlaan 5B, BE-3910 Neerpelt Price: 22,06 Euro T. +32 11 610 510 Orders can be placed at F. +32 11 610 511 www.alamire.com [email protected] EDITOR’S ______NOTE ______ ______ ______ ______ Volume XLIV, Number 5 November 2003 Death and music are no strangers. FEATURES Death is often found in operatic context— A Recorder Icon Interviewed . 8 the tragic ending in Giacomo Puccini’s A Talk with Anthony Rowland-Jones, Tosca when the title figure leaps to her by Sue Groskreutz death, and the stirring music composed by The Recorder in the Nineteenth Century. 16 Richard Wagner for Siegfried’s funeral near by Douglas MacMillan the end of the four-part epic Ring cycle, af- 4 Arranging an Orchestral Work for Recorder Quintet . 22 ter which Brunhilde flings herself on the The eleventh in a series of articles by composers and arrangers hero’s funeral pyre and sings for another discussing how they write and arrange music for recorder, 10 minutes or so. by Carolyn Peskin Death’s knock shows up in Tchaikovsky’s symphonies and, under- scoring the underlying sorrow of war, in DEPARTMENTS the theme song from M*A*S*H—titled Advertiser Index . -

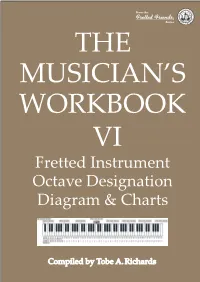

Fretted Instrument Octave Designation Diagram & Charts

ks•Ca oo bo B t t B From the: o o b o a k s C • • C s a k b o o o CB t B B t o o o Series b k a s • C THE MUSICIAN’S WORKBOOK VI Fretted Instrument Octave Designation Diagram & Charts Compiled by Tobe A.Richards FRETTED INSTRUMENT TUNING CHART The comprehesive tuning chart below features each string reading from left to right as if the in- strument was standing up vertically in front of you. Generally, the strings on the left will be lower pitched than those on the right, but there are variations including the mountain dulcimer, where the higher melody strings precede their lower pitched counterparts. The note names are listed in scientific pitch notation as used by The Acoustical Society of Amer- ica. If you need know their Helmholtz equivalents we have a free downloadable/printable ver- sion with both systems and their piano keyboard positioning in Volume VI of our Music Workbook series. You’ll find this in the ‘Freebies’ section of FFM. When discussing the configuration of an instrument’s stringing arrangement, you’ll find they are often referred to by the number of strings or by the number of courses. A course is simply a series of strings tuned to the same note (albeit often an octave apart) to be fretted by one finger at the same time. To give an example of this, the mandolin has 8 strings or 4 courses of strings. Steel strings in particular give a ringing or jangly sound when they are arranged in double, triple or quad- ruple courses. -

FOMRHI Quarterly

No. 32 July 1983 Ehna Da, QortlvQ FOMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 32 2 BULLETIN SUPPLEMENT 9 BOOK NEWS 10 BOUWBRIEFS 60 LIST OF MEMBERS SUPPLEMENT 30 COMMUNICATIONS 464 The Sizes and Pitches of Italian Archlutes by M.Hodgson. 11 465 The Meantone by C.Karp. 17 466 Some notes on Cittern Fingerboards and Stringing by P.Forrester. 19 467 On Restoration by D.Way. 23 468 Lost Traditions - or are they? by J.Montagu. 25 469 Portatives with Reservoirs? by G.Bridges. 27 470 Moisture Blocking of Fipple Flutes by C.Willetts. 29 471 Comments on Bows and their Screws, Taps, Dies and Lathes by G.Mather. 32 472 Put the Gurus out to Grass by D.Z.Crookes. 35 473 Comments on Comm.448 by J.Montagu. 37 474 Acid Staining of Hardwoods by C.Willetts. 38 475 Woodwind Bore Oil by C.Willetts. 39 476 How to make your own Mouldings in Wood by W.D.Hendry. 40 477 What is an Historical Instrument? by E.Segerman. 42 REVIEWS 478- Bagpipes in the Edinburgh University Collection by H.Cheape! 482 Shrine to Music Museum! Instruments of Burma, India, Nepal, Thailand and Tibet! Die Schonsten Musikinstrumente des Altertums by L.Vorreiter! Catalogue of Old Brasswind Instruments by T.Bingham} Ueno Gaknen Collection! J.M. 45 483 Der Zink by F.R.Overton} P.G. 49 FELLOWSHIP OF MAKERS AND RESEARCHERS OF HISTORICAL INSTRUMENTS Hon. Sec. J. Montagu, c/o Faculty of Music, St. Aldate's, Oxford OX1 1DB, U.K. FELLOWSHIP of MAKERS and RESEARC1 Bulletin 52 July, 1985 Not quite as sharp off the mark as I'd hoped, but better than sometimes For a week, I've had an assistant in the Bate (a school-leaver getting work experience, sent by her school) and I didn't want to waste a moment of the opportunity of having someone to help me. -

"The People's Purcell" with Michael Slattery and La Nef

"The People's Purcell" With Michael Slattery and La Nef Tenor Michael Slattery lends his voice to a second project with La Nef. Together they reinvent the most beautiful arias the composer Henry Purcell (1659-1695). Michael Slattery, tenor, shruti box; Sylvain Bergeron, archlute; Seán Dagher, cittern; Grégoire Jeay, flutes; Alex Kehler, nyckelharpa, baroque violin; Amanda Keesmaat, baroque cello; Tanya Laperrière, Baroque violin; Elin Soderstrom, viola da gamba. Artistic Direction, Sylvain Bergeron Musical direction, Seán Dagher Arrangements, Seán Dagher, Grégoire Jeay, Michael Slattery, Amanda Keesmaat Presentation Henry Purcell (1659-1695) represents the height of baroque music in England. He defines the genre, having written a vast quantity of highly regarded music. Despite his great fame and high position in British society, Purcell struck a chord with the common people: his theatrical music both drawing inspiration from and contributing songs and dance tunes to the most popular music of the day. The Purcell Project, presents some of Purcell's very best songs and dances arranged in a variety of styles. As with our earlier exploration of the music of English composer and lutenist John Dowland, we have treated some of Purcell's baroque masterpieces with a certain freedom, permitting ourselves to make adjustments to underlying rhythms and harmonies in order to create altogether new pieces, related to but distinct from the originals. We are not alone in having treated the music this way. During his lifetime, Purcell's music was extremely popular, and shortly after his death his tunes began appearing in John Playford's succession of compilations called “The Dancing Master” alongside popular (and mostly anonymous) folk tunes. -

Medium of Performance for Music: Working List of Terminology

Medium of Performance for Music Working List of Terminology Revised February 2013 Terms listed here are from Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH). The status LCMPT indicates that the Library of Congress (LC) and the Music Library Association (MLA) have agreed that the term is eligible, if not necessarily as a main term or in the form shown in this list, for LCMPT, Library of Congress Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music, which being developed by these two collaborators. The status LCSH means the term will not be added to LCMPT. For a complete list of medium of performance terms LC and MLA have agreed on for LCMPT, see http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/medprf_lcmla.pdf.