Brief Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally!

Made in Melbourne! Enjoyed Nationally & Internationally! JULY 2012 JULY JULY 2012 Issue 92 q comment: GALTA SAYS: ONGOING debate over the topic of ‘gay marriage’ in Australia may confound at the divide it seems Publisher & Editor to represent from the broad social realities of Brett Hayhoe today, where the question of sexual orientation +61 (0) 422 632 690 has almost become ‘ho-hum’, but it also [email protected] reinforces the importance of a clear voice and collective message in representing the unique Editorial needs of the gay and lesbian community, which [email protected] embraces the broader LGBTI groups. Sales and Marketing [email protected] Travel is a good case-in-point. Gay and lesbian travellers visit the same places and seek the same Design holiday benefits as all travellers do, but there are also Uncle Brett Designs & Graphics distinctive needs that still define this arena as a niche segment of the market. Contributing Writers Evan Davis, Alan Mayberry, Tasman Anderson, According to Mr Rod Stringer, Managing Director of Barrie Mahoney, Brett Hayhoe, Chris peak industry membership body, Gay and Lesbian Gregoriou, Pete Dillon, Matthew Baker- Tourism Australia (GALTA), there is a continuing role Johnson, Marc J Porter, Nathan Miller for specific marketing and representation that is Cover picture focussed on connecting travellers to the right hosts, as Baan Souy Resort, Pattaya Thailand well as working to improve awareness of the nuances within the niche. Photographic Contributions Alan Mayberry (gh, q drag), Mathew “While pride or community events are popular travel Badenach (flamingos), Daniel Mar- motivators for the gay and lesbian community, all tin Bailey (dnm) travellers share a universal desire to explore new destinations and to feel welcome and comfortable [email protected] while on holiday,” Mr Stringer said. -

Brennan O'rear Principal Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Financial Services

Brennan O'Rear Principal Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Financial Services Cofounder at SpendVest, LLC Current Instructional Media & Magic, Meadows & Previous Associates BA, International Relations at American Education University Experience Cofounder SpendVest, LLC January 2012 – Present (11 months) Philadelphia, PA SpendVest is a startup whose mission is to make consumers owners. We help consumers more easily accrue equity in companies they love and trust. Lead Researcher Instructional Media & Magic 2009 – 2011 (2 years) Research focused on financial instruments by which to increase the volume of private sector capital available to finance higher education. Brennan has 1 recommendation including: • James Farmer, Owner, instructional media + magic, inc. Associate 1 From www.linkedin.com/profile/view?id=10502016&locale=en_US&trk=tyah 9 November 2012 Meadows & Associates 2006 – 2008 (2 years) Washington D.C. Metro Area Management consultation focused on systems organization and governance. Recommend Brennan’s work at Meadows & Associates Education American University BA, International Relations 2002 – 2006 President, Golden Key Honor Society American University Honors Program Graduated Summa Cum Laude Activities and Societies: Focused on political economy with a smattering of Spanish, French, & political philosophy thrown in for good measure. George School Lead Researcher Instructional Media & Magic “His research was relevant, precise, and well documented. His work brings new insight into financing college and university students. His publications have rated high in readership and citation.” November 9, 2012 James Farmer, Owner, instructional media + magic, inc. managed Brennan indirectly at Instructional Media & Magic 2 From www.linkedin.com/profile/view?id=10502016&locale=en_US&trk=tyah 9 November 2012 Brennan’s Connections Giacomo Abrusci 2nd Environmental analyst, junior scientist, communications specialist, hard worker and eager to apply to new opportunities. -

A Fitting End to the Ill·Fitting American Suit

OMSAIRAM Afitting end to the ill·fitting American suit Asuitable man to spark amen's clothing revolution months. He and his team take over hotel suites in major cities, so American customers can make an appointment and get the full Kowloon Monty. AMERICAN CLOTHING CHAIN STORE HAS MUCH TO FEAR FROM MR. DASWANI Measurements and digital photos are Consider this proposition. Would you wouldn't feel right sitting at home. taken here and emailed to Hong rather pay the same sum for a single, It's not a business. It's a mission. Kong. Often, your suit will be started off-the-peg, chain store suit cut by a 'I love seeing customers walk in a on by a tailor 10,000 miles away before you've even left the hotel. You comput~r and sold to you by a spotty really bad suit that cost them a boy who thinks side vents are to be fortune and walk out in one of our can have it couriered within 3 weeks, found on a Lambretta scooter, or for suits that's perfect in every way, or wait for a second fitting when the two bespoke, custom cut, hand- made with a good heart in a superior Raja team hits your town again. stitched suits, measured and sold to fabric for a half or a quarter as much.' It now remains to see whether the you by a man for whom suits are a The price of a Daswani shirt and suit Raja revolution, with its inspired mix lifetime's passion? are astonishing. -

The Masterpiece:A Drama-Based

, Universidad de Jaén Centro de Estudios de Postgrado Trabajo Fin de Máster y Enseñanza Idiomas de y Enseñanza THE MASTERPIECE: A DRAMA-BASED DIDACTIC UNIT rado de Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria Secundaria de rado Enseñanza Alumno/a: Blanca Machuca, Manuel de la Tutor/a: Julio Ángel Olivares Merino r Profeso en Centro de Estudios de Estudios Postgrado de Centro Dpto: Filología Inglesa Bachillerato, Formación Profesional Bachillerato, Máste Octubre, 2020 1 Mes, Año Table of Contents 0. Abstract ....................................................................................................................... 3 PART I: EPISTEMIC FOUNDATIONS ............................................................................................. 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 2. Bibliographical Review.................................................................................................. 5 3. Justification to the Methodology................................................................................... 8 3.1 Objectives ............................................................................................................16 3.2 Contents ..............................................................................................................18 3.3 Transversal and Cross-cultural issues ....................................................................22 3.4 Attention to Diversity ...........................................................................................24 -

Marenisco Hearing Addresses Recreational Marijuana Enterprise by P.J

Call (906) 932-4449 Ironwood, MI Baseball Hurley beats Mellen Redsautosales.com 6-5 SPORTS • 9 DAILY GLOBE Tuesday, May 14, 2019 Chance of thunderstorms yourdailyglobe.com | High: 68 | Low: 45 | Details, page 2 Marenisco hearing addresses recreational marijuana enterprise By P.J. GLISSON [email protected] MARENISCO – Close to 100 people filled the community room of the Marenisco Town Hall for a Monday evening public hearing on a proposed marijuana ordinance that would allow recre- ational marijuana enterprise. “There will be no catcalls,” said Marenisco supervisor Richard Bouvette while opening the floor to questions and com- ments. Although the hearing allowed the public to vent its concerns, Bouvette said members of the township board then would be the ones to vote for or against the ordinance. “The township board may not institute an election according to its own interest,” said Bouvette regarding its earlier speculation that it could do just that. “As far as I’m concerned, this would have been the easiest thing to do.” Instead, he explained, state P.J. Glisson/Daily Globe law dictates that if the public AT A MONDAY evening hearing on a proposed ordinance in relation to recreational marijuana facilities, Marenisco Township supervi- does not like the board’s vote, sor Richard Bouvette addresses the crowd, which filled the community room of the Marenisco Township Hall. “You have the right to petition, and then it would go to ballot.” includes edibles. lowing: –Three safety compliance Micro-businesses could exist Township attorney Jim Buck- He added that an advantage of –Three provisioning centers facilities; and in any zoning division except res- nell, who wrote the ordinance, recreational marijuana being or public retail sales locations –Three secure transporters. -

Report of the Special Arbitrator on the Expense Claims Identified by the Auditor General in His Report Dated June 4, 2015

REPORT OF THE SPECIAL ARBITRATOR ON THE EXPENSE CLAIMS IDENTIFIED BY THE AUDITOR GENERAL IN HIS REPORT DATED JUNE 4, 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 The Audit Period ..............................................................................................................................1 Part One: Executive Summary ........................................................................................................1 Senators Occupy a Position of Public Trust ..............................................................................2 The Dominant or Primary Purpose of Expenditure of Public Money .......................................3 An Assessment of Reasonableness ............................................................................................4 The Cost Benefit Question .........................................................................................................4 Proportionality ...........................................................................................................................5 Evidence in The Special Arbitration ..........................................................................................6 Conclusion of the Special Arbitration........................................................................................7 Part Two: Background ....................................................................................................................8 -

Rotary Global Rewards Vendor Offers As of September 1, 2018

ENGLISH (EN) ROTARY GLOBAL REWARDS VENDOR OFFERS AS OF SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 Use this list to find offers available* on Rotary Global Rewards *Please note that vendor offers are subject to change without notice. Country Code Key: ae: United Arab Emirates gg: Guernsey pa: Panama af: Afghanistan gl: Greenland pe: Peru am: Armenia gr: Greece ph: Philippines ar: Argentina gu: Guam pk: Pakistan at: Austria hk: Hong Kong pl: Poland au: Australia hr: Croatia pr: Puerto Rico bd: Bangladesh hu: Hungary pt: Portugal be: Belgium id: Indonesia qa: Qatar bg: Bulgaria ie: Ireland ro: Romania bn: Brunei Darussalam in: India rs: Serbia br: Brazil iq: Iraq ru: Russia bs: Bahamas is: Iceland sa: Saudi Arabia bt: Bhutan it: Italy sc: Seychelles ca: Canada jp: Japan se: Sweden ch: Switzerland jo: Jordan sg: Singapore ck: Cook Islands kh: Cambodia si: Svalbard and Jan Mayen cl: Chile kr: Korea Islands cn: China ky: Cayman Islands sk: Slovakia co: Colombia lk: Sri Lanka sm: San Marino cr: Costa Rica lu: Luxembourg sr: Suriname cz: Czech Republic me: Montenegro th: Thailand de: Germany mk: Macedonia tr: Turkey dk: Denmark mn: Mongolia tw: Taiwan do: Dominican Republic mo: Macao tz: Tanzania ec: Ecuador mx: Mexico us: United States of America ee: Estonia my: Malaysia uz: Uzbekistan eg: Egypt ng: Nigeria ve: Venezuela es: Spain nl: Holland vi: Virgin Islands fi: Finland no: Norway vn: Vietnam fj: Fiji np: Nepal za: South Africa fr: France nz: New Zealand zm: Zambia gb: United Kingdom om: Oman Rotary Global Rewards Vendor Offer List (September 2018) 1 .Italo (NTV) -

January 2013

JANUARY 2013 Happy New Year! St. Andrews International School Sathorn • Sukhumvit 107• Green Valley AD Nurture St. Andrews International School Early Years curriculum provides a rich experience combining play, culture and the roots of structured learning. Challenge Our Primary School curriculum challenges students to think independently, helping them develop into adaptive, thoughtful and active global citizens. Excel Graduating our Secondary School with IGSCE’s and the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme, students achieve their absolute best academically and socially. Accepting applications now! www.standrews-schools.com [email protected] St. Andrews International School Sathorn • Sukhumvit 107• Green Valley Nurture St. Andrews International School Early Years curriculum provides a rich experience combining play, culture and the roots of structured learning. Challenge Our Primary School curriculum challenges students to think independently, helping them develop into adaptive, thoughtful and active global citizens. Excel Graduating our Secondary School with IGSCE’s and the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme, students achieve their absolute best academically and socially. Accepting applications now! www.standrews-schools.com [email protected] Ad Innnity Size: 210 x 297 MM RELIABLE QUALITY SUPERB VA LU E IMPECC ABLE SERVICE Providing high quality custom tailoring for more than 45 years, Raja’s Fashions has been featured in Men's Vogue Magazine, International Living, Worth Magazine, Esquire, Fortune, Bangkok Guide, Lonely Planet, Frommer’s Guide, Fodor’s Guide, The Washington Post, Vivre A Bangkok, Conde Nast Magazine and many other travel magazines. NE W LOCATIO N . T HE SAM E RAJA S EXP ERI ENCE. DRESS SHARP. LO O K SHARP. FEEL SHARP. -

Happy New Year! St

JANUARY 2013 Happy New Year! St. Andrews International School Sathorn • Sukhumvit 107• Green Valley AD Nurture St. Andrews International School Early Years curriculum provides a rich experience combining play, culture and the roots of structured learning. Challenge Our Primary School curriculum challenges students to think independently, helping them develop into adaptive, thoughtful and active global citizens. Excel Graduating our Secondary School with IGSCE’s and the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme, students achieve their absolute best academically and socially. Accepting applications now! www.standrews-schools.com [email protected] St. Andrews International School Sathorn • Sukhumvit 107• Green Valley Nurture St. Andrews International School Early Years curriculum provides a rich experience combining play, culture and the roots of structured learning. Challenge Our Primary School curriculum challenges students to think independently, helping them develop into adaptive, thoughtful and active global citizens. Excel Graduating our Secondary School with IGSCE’s and the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme, students achieve their absolute best academically and socially. Accepting applications now! www.standrews-schools.com [email protected] Ad Innnity Size: 210 x 297 MM RELIABLE QUALITY SUPERB VA LU E IMPECC ABLE SERVICE Providing high quality custom tailoring for more than 45 years, Raja’s Fashions has been featured in Men's Vogue Magazine, International Living, Worth Magazine, Esquire, Fortune, Bangkok Guide, Lonely Planet, Frommer’s Guide, Fodor’s Guide, The Washington Post, Vivre A Bangkok, Conde Nast Magazine and many other travel magazines. NE W LOCATIO N . T HE SAM E RAJA S EXP ERI ENCE. DRESS SHARP. LO O K SHARP. FEEL SHARP. -

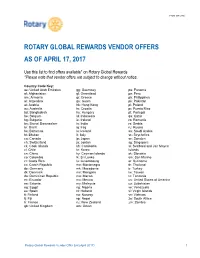

Rotary Global Rewards Vendor List Apr2017 EN

ENGLISH (EN) ROTARY GLOBAL REWARDS VENDOR OFFERS AS OF APRIL 17, 2017 Use this list to find offers available* on Rotary Global Rewards *Please note that vendor offers are subject to change without notice. Country Code Key: ae: United Arab Emirates gg: Guernsey pa: Panama af: Afghanistan gl: Greenland pe: Peru am: Armenia gr: Greece ph: Philippines ar: Argentina gu: Guam pk: Pakistan at: Austria hk: Hong Kong pl: Poland au: Australia hr: Croatia pr: Puerto Rico bd: Bangladesh hu: Hungary pt: Portugal be: Belgium id: Indonesia qa: Qatar bg: Bulgaria ie: Ireland ro: Romania bn: Brunei Darussalam in: India rs: Serbia br: Brazil iq: Iraq ru: Russia bs: Bahamas is: Iceland sa: Saudi Arabia bt: Bhutan it: Italy sc: Seychelles ca: Canada jp: Japan se: Sweden ch: Switzerland jo: Jordan sg: Singapore ck: Cook Islands kh: Cambodia si: Svalbard and Jan Mayen cl: Chile kr: Korea Islands cn: China ky: Cayman Islands sk: Slovakia co: Colombia lk: Sri Lanka sm: San Marino cr: Costa Rica lu: Luxembourg sr: Suriname cz: Czech Republic me: Montenegro th: Thailand de: Germany mk: Macedonia tr: Turkey dk: Denmark mn: Mongolia tw: Taiwan do: Dominican Republic mo: Macao tz: Tanzania ec: Ecuador mx: Mexico us: United States of America ee: Estonia my: Malaysia uz: Uzbekistan eg: Egypt ng: Nigeria ve: Venezuela es: Spain nl: Holland vi: Virgin Islands fi: Finland no: Norway vn: Vietnam fj: Fiji np: Nepal za: South Africa fr: France nz: New Zealand zm: Zambia gb: United Kingdom om: Oman Rotary Global Rewards Vendor Offer List (April 2017) 1 180 Nutrition au 1800 -

Bangkok-13-Preview.Pdf

Plan Your Trip 12 ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Bangkok “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over. So go!” TONY WHEELER, COFOUNDER – LONELY PLANET Austin Bush, Tim Bewer, Anita Isalska, Andy Symington Contents PlanPlan Your Your Trip Trip page 1 4 Welcome to Bangkok ..... 4 Top Itineraries ............... 18 Drinking & Nightlife .... 35 Bangkok’s Top 10 ........... 6 If You Like ...................... 20 Entertainment ............ 39 What’s New .................... 13 Month by Month ........... 22 Shopping ...................... 43 Need to Know ................ 14 With Kids ....................... 24 Sports & Activities .... 48 First Time Bangkok ....... 16 Eating ........................... 26 LGBT Bangkok ............ 52 Explore Bangkok 54 Neighbourhoods Chinatown ..................... 98 Sukhumvit .................. 142 at a Glance .................. 56 Siam Square, Northern Bangkok ..... 156 Ko Ratanakosin Pratunam, Phloen Chit Excursions & Thonburi .................... 58 & Ratchathewi ............ 108 from Bangkok ........... 167 Banglamphu ................. 77 Riverside, Silom & Lumphini ................. 125 Sleeping ..................... 189 Thewet & Dusit ............. 90 Understand Bangkok 205 Bangkok Today .......... 206 People & Culture ........ 218 The Sex Industry in Thailand .................. 231 History ......................... 208 Food & Drink ............... 225 Survival Guide 235 Transport .................... 236 Language .................... 248 Directory A-Z ............... 241 Index -

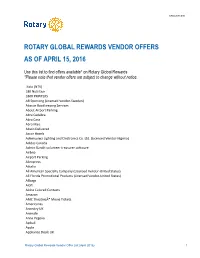

Rotary Global Rewards Vendor List Apr2016 EN

ENGLISH (EN) ROTARY GLOBAL REWARDS VENDOR OFFERS AS OF APRIL 15, 2016 Use this list to find offers available* on Rotary Global Rewards *Please note that vendor offers are subject to change without notice. .Italo (NTV) 180 Nutrition 1800 PRINTERS AB Sporrong (Licensed Vendor-Sweden) Abacus Bookkeeping Services About Airport Parking Abra Cadabra Abra Casa Abra Mais Absco Delivered Accor Hotels Ademuyiwa Lighting and Electronics Co. Ltd. (Licensed Vendor-Nigeria) Adidas Canada Admin Bandit volunteer treasurer software Airbnb Airport Parking Aliexpress Alitalia All American Specialty Company (Licensed Vendor-United States) All Florida Promotional Products (Licensed Vendor-United States) Allbags Aloft Aloha Colored Contacts Amazon AMC Theatres® Movie Tickets Americanas Ancestry UK Animale Anna Pegova Apikali Apple Appliance Deals UK Rotary Global Rewards Vendor Offer List (April 2016) 1 Apps4Rent Arcussi Jewellery and Handbag Store Argos UK Articulos Publicitarios Imagen (Licensed Vendor-Mexico) Ashop - New Zealand Health, Skincare, Organic Products To The World Asports Atlanta CityPASS Attitude Clothing UK Auckland City and Airport Car Rental Australia Gift Shop Australian Flag Makers Autodesk Europe AVIS Rent-A-Car AZOD.com.au B&Q Baby Bahia Principe Hotels Balao da Informatica Banana Republic Canada Bank of America (Canada only) Bank of America (US only) Barcelo BBC Canada Beauty Expert UK Beba Store Bed Bath & Beyond Bed Bath And Beyond Canada Bee Fitness Beleza na Web Belowcepek.com (Indonesia) Berlin Rotary Club (Licensed Vendor-United