Chapter 3 to Crossed Swords: Entanglements Between Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar ______

THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR ___________________________ by Dan Gurskis based on the play by William Shakespeare THE TRAGEDY OF JULIUS CAESAR FADE IN: A STATUE OF JULIUS CAESAR in a modern military dress uniform. Then, after a moment, it begins. First, a trickle. Then, a stream. Then, a rush. The statue is bleeding from the chest, the neck, the arms, the abdomen, the hands — dozens of wounds. DISSOLVE TO: EXT. HILLY COUNTRYSIDE — DAY Late winter. The ground is mottled with patches of snow and ice. BURNED IN are the words: "Kosovo, soon after the unrest." Somewhere in the distance, an open-topped Jeep bounces along a rutted, twisting road. INT. OPEN-TOPPED JEEP — MOVING FLAVIUS and MARULLUS, two military officers in uniform, occupy the front passenger's seat and the rear seat, respectively. An ENLISTED MAN is behind the wheel. The three ride in silence for a moment, huddled against the cold, wind whipping through their hair. There is a casual almost careless air to the men. If they do not feel invincible, they feel at the very least unconcerned. Even the machine gun mounted on the rear of the Jeep goes unattended. Just then, automatic sniperfire RINGS OUT of the surrounding woods. The windshield SHATTERS. The driver's forehead explodes in a spray of blood and bone. He slumps over the steering wheel, pulling it hard to the side. ANGLE ON THE JEEP swerving off the road, flipping down an embankment. All three men are thrown from the Jeep, which comes to rest on its side. The driver, clearly dead, lies wide-eyed in a ditch. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

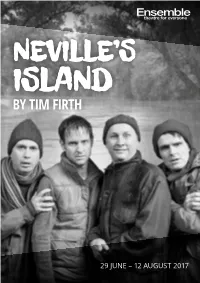

12 AUGUST 2017 “For There Is Nothing Either Good Or Bad, but Thinking Makes It So.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

29 JUNE – 12 AUGUST 2017 “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2. Ramsey Island, Dargonwater. Friday. June. DIRECTOR ASSISTANT DIRECTOR MARK KILMURRY SHAUN RENNIE CAST CREW ROY DESIGNER ANDREW HANSEN HUGH O’CONNOR NEVILLE LIGHTING DESIGNER DAVID LYNCH BENJAMIN BROCKMAN ANGUS SOUND DESIGNER DARYL WALLIS CRAIG REUCASSEL DRAMATURGY GORDON JANE FITZGERALD CHRIS TAYLOR STAGE MANAGER STEPHANIE LINDWALL WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER SLADE BLANCH / DANI IRONSIDE Jacqui Dark as Denise, WARDROBE COORDINATOR Shaun Rennie as DJ Kirk, ALANA CANCERI Vocal Coach Natasha McNamara, MAKEUP Kanen Breen & Kyle Rowling PEGGY CARTER First performed by Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough in May 1992. NEVILLE’S ISLAND @Tim Firth Copyright agent: Alan Brodie Representation Ltd. www.alanbrodie.com RUNNING TIME APPROX 2 HOURS 10 MINUTES INCLUDING INTERVAL 02 9929 0644 • ensemble.com.au TIM FIRTH – PLAYWRIGHT Tim’s recent theatre credits include the musicals: THE GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination), THIS IS MY FAMILY (UK Theatre Award Best Musical), OUR HOUSE (West End, Olivier Award Best Musical) and THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY. His plays include NEVILLE’S ISLAND (West End, Olivier Nomination), CALENDAR GIRLS (West End, Olivier Nomination) SIGN OF THE TIMES (West End) and THE SAFARI PARTY. Tim’s film credits include CALENDAR GIRLS, BLACKBALL, KINKY BOOTS and THE WEDDING VIDEO. His work for television includes MONEY FOR NOTHING (Writer’s Guild Award), THE ROTTENTROLLS (BAFTA Award), CRUISE OF THE GODS, THE FLINT STREET NATIVITY and PRESTON FRONT (Writer’s Guild “For there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.“ Award; British Comedy Award, RTS Award, BAFTA nomination). -

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene Ii

Grade 10 Literature Mini-Assessment Excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare This grade 10 mini-assessment is based on an excerpt from Julius Caesar, Act III, Scene ii by William Shakespeare and a video of the scene. This text is considered to be worthy of students’ time to read and also meets the expectations for text complexity at grade 10. Assessments aligned to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will employ quality, complex texts such as this one. Questions aligned to the CCSS should be worthy of students’ time to answer and therefore do not focus on minor points of the text. Questions also may address several standards within the same question because complex texts tend to yield rich assessment questions that call for deep analysis. In this mini- assessment there are seven selected-response questions and one paper/pencil equivalent of technology enhanced items that address the Reading Standards listed below. Additionally, there is an optional writing prompt, which is aligned to both the Reading Standards for Literature and the Writing Standards. We encourage educators to give students the time that they need to read closely and write to the source. While we know that it is helpful to have students complete the mini-assessment in one class period, we encourage educators to allow additional time as necessary. Note for teachers of English Language Learners (ELLs): This assessment is designed to measure students’ ability to read and write in English. Therefore, educators will not see the level of scaffolding typically used in instructional materials to support ELLs—these would interfere with the ability to understand their mastery of these skills. -

Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center

THE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE CENTER STUDY GUIDE Julius Caesar © 2015 American Shakespeare Center. All rights reserved. The following materials were compiled by the Education and Research Department of the American Shakespeare Center, 2015. Created by: Cass Morris, Academic Resources Manager; Sarah Enloe, Director of Education and Research; Ralph Cohen, ASC Executive Founding Director and Director of Mission; Jim Warren, ASC Artistic Director; Jay McClure, Associate Artistic Director; ASC Actors and Interns. Unless otherwise noted, all selections from Julius Caesar in this study guide use the stage directions as found in the 1623 Folio. All line counts come from the Norton Shakespeare, edited by Stephen Greenblatt et al, 1997. The American Shakespeare Center is partially supported by a grant from the Virginia Commission for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. American Shakespeare Center Study Guides are part of Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest. -2- Dear Fellow Educator, I have a confession: for almost 10 years, I lived a lie. Though I was teaching Shakespeare, taking some joy in pointing out his dirty jokes to my students and showing them how to fight using air broadswords; though I directed Shakespeare productions; though I acted in many of his plays in college and professionally; though I attended a three-week institute on teaching Shakespeare, during all of that time, I knew that I was just going through the motions. Shakespeare, and our educational system’s obsession with him, was still a bit of a mystery to me. -

A Declaration of Interdependence: Peace, Social Justice, and the “Spirit Wrestlers” John Elfers Sofia University

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 32 | Issue 2 Article 12 7-1-2013 A Declaration of Interdependence: Peace, Social Justice, and the “Spirit Wrestlers” John Elfers Sofia University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, Religion Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Elfers, J. (2013). Elfers, J. (2013). A declaration of interdependence: Peace, social justice, and the “spirit wrestlers.” International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 32(2), 111–121.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 32 (2). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ ijts.2013.32.2.111 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Declaration of Interdependence: Peace, Social Justice, and the “Spirit Wrestlers” John Elfers Sofia University Palo Alto, CA, USA The struggle between the Doukhobors, a nonviolent society committed to communal values, and the Canadian Government epitomizes the tension between values of personal rights and independence on the one hand, and social obligation on the other. The immigration of the Doukhobors from Russia to the Canadian prairies in 1899 precipitated a century- long struggle that brings issues of social justice, moral obligation, political authority, and the rule of law into question. The fundamental core of Western democracies, founded on the sanctity of individual rights and equal opportunity, loses its potency in a community that holds to the primacy of interdependence and an ethic of caring. -

The Imperial Cult and the Individual

THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Department of Ancient Mediterranean Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by CLAIRE McGRAW Dr. Dennis Trout, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2019 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled THE IMPERIAL CULT AND THE INDIVIDUAL: THE NEGOTIATION OF AUGUSTUS' PRIVATE WORSHIP DURING HIS LIFETIME AT ROME presented by Claire McGraw, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________________ Professor Dennis Trout _______________________________________________ Professor Anatole Mori _______________________________________________ Professor Raymond Marks _______________________________________________ Professor Marcello Mogetta _______________________________________________ Professor Sean Gurd DEDICATION There are many people who deserve to be mentioned here, and I hope I have not forgotten anyone. I must begin with my family, Tom, Michael, Lisa, and Mom. Their love and support throughout this entire process have meant so much to me. I dedicate this project to my Mom especially; I must acknowledge that nearly every good thing I know and good decision I’ve made is because of her. She has (literally and figuratively) pushed me to achieve this dream. Mom has been my rock, my wall to lean upon, every single day. I love you, Mom. Tom, Michael, and Lisa have been the best siblings and sister-in-law. Tom thinks what I do is cool, and that means the world to a little sister. -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D. -

The Conversion of Rome Notes

The Conversion of Rome Intro: This lesson will cover the beginning of Christendom - when the church became united to the state and Christianity became a dominant cultural influence in the Roman Empire. Constantine -Reigned from 306-337. -He was a coemperor with Licinius between 311 and 324. -He was the illegitimate son of a Roman military leader (Constantius) and a Christian freedwoman named Helena. -Even before his conversion, Constantine thought that Christianity could be used to help save classical culture; Christianity had practical benefits even if it was untrue. -He founded one of the most important cities in history and named it after himself - “Constantinople.” In This Sign Conquer In 312 Constantine was overwhelmed at a Battle at the Milvian bridge over the Tiber River. He was fighting a rival to the imperial throne named Maxentius. He supposedly had a vision of a Christian symbol with the Latin phrase “In Hoc Signo Vinces” (“in this sign conquer”). He had his troops put a XP (chi-rho, the first two letters of the word “Christ” in Greek) on their shields and banners. He won this battle and took the victory as a sign of favor from the Christian God. However, some think that the real reason Constantine promoted Christianity was because it could unite his fracturing empire. In 313 he passed the Edict of Toleration which made Christianity a religio licita (legal religion). Christianity had gone from being illegal to being an official religion of the Roman Empire overnight. Churches were given their property back and subsidized by the state, clergy were exempted from public service, and Sunday was declared an official day of rest and worship (which was the same day that the cult of the “invincible sun” worshipped its god). -

Christ and Culture in America: Civil Religion and the American Catholic Church

Christ and Culture in America: Civil Religion and the American Catholic Church Author: Philip Sutherland Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/bc-ir:107479 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2017 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Christ and Culture in America: Civil Religion and the American Catholic Church Submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Licentiate in Sacred Theology by Philip Sutherland, S.J. 4/24/17 Readers: Dr. Mark Massa, S.J. Dr. Dominic Doyle Introduction Civil religion is a necessary unifying force in a religiously plural society such as the United States, but it can also usurp the place of Christianity in the believer’s life. This is always a danger for Christianity which is can only be the “good news” if it is inculturated by drawing upon a society’s own symbols. But it must also transcend the culture if it is to speak a prophetic word to it. Ever since Bellah’s article about civil religion in America, there has been disagreement about the theological value of civil religion. Reinhold Niebuhr, James McEvoy and Will Herberg have argued that civil religion will inevitably replace transcendent religion in people’s lives. Bellah, John F. Wilson and others argue instead that civil religion is necessary to develop the social bonds that hold modern secular societies together. Civil religion produces patriotism, a devotion and attachment to one’s country, which is an important source of civic and communal identity. -

1/10/77 - Remarks at the Closing of the Ceremony Presenting Medals of Freedom” of the President’S Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 42, “1/10/77 - Remarks at the Closing of the Ceremony Presenting Medals of Freedom” of the President’s Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 42 of President's Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library CLOSING REMARKS FOR MEDAL OF FREEDOM PRESENTATION -I- LET ME CONGRATULATE EACH AND EVERY ONE OF YOUe - 4 ·~ I REGRET THAT IRVING BERLIN, THE LATE ALEXANDER CALDER\ AND GEORG lA O'KEEFFE WERE UNABLE TO BE REPRESENTED HERE TODAY. ~ WE WILL W PREEE11Tif4S THEIR MEDALS TO THEM.......- OR TO THEIR FAMILIES AT A LATER DATE. -2- IN ClOSING\lET ME VOICE OUR COUNTRY'S GRATITUDE\ NOT ONLY T~ Y~ \BUT TO ALL THOSE WHO HELPED YOU ACHIEVE WHAT YOU Dl De EACH OF YOU HAS HAD FRIENDS AND C~WORKERS\(_AMMATES AND -~~MILIES WHO S~E IN YOUR ACHIEVEMENTS \\AND IN OUR PRIDE TODAYe ONCE AGAIN, \ CONGRATUlATI ONSe -3- NOW BETTY AND I WILL JOIN THE HO\JOREES IN THE GRAND HALL TO .MEET.... -

The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers

OriginalverCORE öffentlichung in: A. Erskine (ed.), A Companion to the Hellenistic World,Metadata, Oxford: Blackwell citation 2003, and similar papers at core.ac.uk ProvidedS. 431-445 by Propylaeum-DOK CHAPTKR TWENTY-FIVE The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers Anßdos Chaniotis 1 Introduction: the Paradox of Mortal Divinity When King Demetrios Poliorketes returned to Athens from Kerkyra in 291, the Athenians welcomed him with a processional song, the text of which has long been recognized as one of the most interesting sources for Hellenistic ruler cult: How the greatest and dearest of the gods have come to the city! For the hour has brought together Demeter and Demetrios; she comes to celebrate the solemn mysteries of the Kore, while he is here füll of joy, as befits the god, fair and laughing. His appearance is majestic, his friends all around him and he in their midst, as though they were stars and he the sun. Hail son of the most powerful god Poseidon and Aphrodite. (Douris FGrH76 Fl3, cf. Demochares FGrH75 F2, both at Athen. 6.253b-f; trans. as Austin 35) Had only the first lines of this ritual song survived, the modern reader would notice the assimilaüon of the adventus of a mortal king with that of a divinity, the etymo- logical association of his name with that of Demeter, the parentage of mighty gods, and the external features of a divine ruler (joy, beauty, majesty). Very often scholars reach their conclusions about aspects of ancient mentality on the basis of a fragment; and very often - unavoidably - they conceive only a fragment of reality.