1 Forward Search, Pattern Recognition and Visualization in Expert Chess: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999/6 Layout

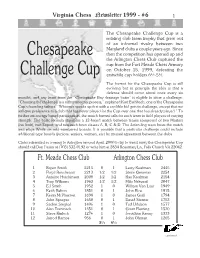

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

Altogether Now in My Decades of Playing Sub-Optimal Chess, I Have

Altogether now In my decades of playing sub-optimal chess, I have been given several pieces of advice about how best to play simultaneous chess. I have faced several grandmasters over the board in simuls and tried to adopt these tips, but with very little success. In fact, no success. One suggestion was to tactically muddy the waters. The theory being if you play a closed positional game the GM (or whoever is giving the simul) will easily overcome you end in the end with their superior technique. On the other hand, although they are, of course, much better than you tactically if they have 20 odd other boards to focus on, effectively playing their moves at a rate akin to blitz, there is a chance they might slip up and give you some winning chances when faced with a messy position. This is fine in theory and may work well for those players stronger then myself who are adept at tactics but my record of my games shows a whopping nil points for me with this approach. In fact, I have found the opposite to be true. I am pleased to report that I have achieved a couple of draws from playing a completely blocked stagnant position. The key here has been to try to make the games last sufficiently long so that in the end then GM kindly offers you a draw in a desperate attempt to get his last bus home. Although loathsome this is when you want as many of those horrible creatures who play on when they are a rook and a bishop down with no compensation (or similar) to keep on playing against the GM. -

PNWCC FIDE Open – Olympiad Gold

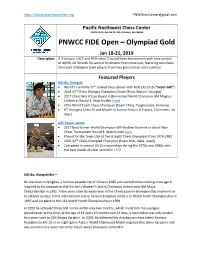

https://www.pnwchesscenter.org [email protected] Pacific Northwest Chess Center 12020 113th Ave NE #C-200, Kirkland, WA 98034 PNWCC FIDE Open – Olympiad Gold Jan 18-21, 2019 Description A 3-section, USCF and FIDE rated 7-round Swiss tournament with time control of 40/90, SD 30 with 30-second increment from move one, featuring two Chess Olympiad Champion team players from two generations and countries. Featured Players GM Bu, Xiangzhi • World’s currently 27th ranked chess player with FIDE Elo 2726 (“Super GM”) • 2018 43rd Chess Olympia Champion (Team China, Batumi, Georgia) • 2017 Chess World Cup Round 4 (Eliminated World Champion GM Magnus Carlsen in Round 3. Watch video here) • 2015 World Team Chess Champion (Team China, Tsaghkadzor, Armenia) • 6th Youngest Chess Grand Master in human history (13 years, 10 months, 13 days) GM Tarjan, James • 2017 Beat former World Champion GM Vladimir Kramnik in Isle of Man Chess Tournament Round 3. Watch video here • Played for the Team USA at five straight Chess Olympiads from 1974-1982 • 1976 22nd Chess Olympiad Champion (Team USA, Haifa, Israel) • Competed in several US Championships during the 1970s and 1980s with the best results of clear second in 1978 GM Bu, Xiangzhi Bio – Bu was born in Qingdao, a famous seaside city of China in 1985 and started chess training since age 6, inspired by his compatriot GM Xie Jun’s Women’s World Champion victory over GM Maya Chiburdanidze in 1991. A few years later Bu easily won in the Chinese junior championship and went on to achieve success in the international arena: he won 3rd place in the U12 World Youth Championship in 1997 and 1st place in the U14 World Youth Championship in 1998. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

Christmas in Pamplona for the Running of the Pawns

‘g’ file exposes the Black king even more. Jakovenko, D- Illescas Cordoba, M January 6th 2007 24.g2xf3 Kg8-h7 Pamplona 2006 25.Rc1–d1 Qd5xa2 The young Russian player Black is forced to win has menacingly massed his another pawn, but the pieces on the kingside so queen is driven offside. Illescas tried to bring his knight over to aid the 26.Ke1–f2 Rf8-f6 defence. 27.Rh1–g1 Ra8-f8 Christmas in 24… Nc7-e8 The hazardous nature of Pamplona Black's position is If 24...Ra8-d8 25.Re3-g3 demonstrated by the fact sets up a decisive sacrifice for the that this natural move loses on g6. by force. Correct was running of 27...Qa2-b3 inching the 25.Ne5xf7 queen back into the game. White has a choice of the pawns 28.Bf4-e5 Nd7xe5 strong moves, 25.Bd3xg6 Chess professionals don’t 29.Qe2xe5 Nb6-d7 f7xg6 26.Re3-g3 was also always get to put their very tempting. feet up over Christmas, as There is no good alternative some tournaments are but this meets with a brutal 25...Rd4xd3 traditionally held during response. this period. This year all XABCDEFGHY Capturing the knight doesn’t eyes were on Pamplona, 8-+-+-tr-+( work: 25...Qg7xf7 where the organisers 7zpp+n+-+k' 26.Re3xe6 Rd4xd3 27.Qh4- assembled an attractive 6-+-sNltr-zp& h8+ Qf7-g8 28.Re6xe8+ field with many strong, 5+Lzp-wQp+-% Ra8xe8 29.Re1xe8+ imaginative, attacking 4-+-+-+-zP$ Kf8xe8 30.Qh8xg8+ leaves players. 3+-+-+P+-# White a queen to the good. -

BLINDFOLD CHESS -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

This is the case with postcard strongest players in Paris and BLINDFOLD CHESS and even email play but changed won with a resounding score of Dr. A.Chatterjee <[email protected]> with the advent of server play as 6 wins and 2 draws. the graphical board appears on hat did the great actual blindfolding is not a the computer screen as soon as players Philidor, requirement – the master may you access the opponents move. WAlekhine, Najdorf and simply have his back turned Good OTB players too, are Koltanowski have in common? away from an opponent sitting skilled visualisers as well. They were all virtuoso blindfold at the board, or more usually, he Indeed the process of playing a exponents. is in a separate room with normal OTB game consists of Though chess is not often neither chess board, pen and looking far ahead of the current thought of as a spectator sport, paper or any electronic device. position albeit with the board in strong chess players, posses an The moves are relayed by a sight, but not moving the pieces. innate talent that can often result neutral person. As with the game of chess in spectacular displays. Child itself, blindfold chess is thought prodigies getting the better of to have had its beginnings in veterans, simultaneous displays, India. However, the first memory feats and blindfold performer of this feat to gain chess are some of the world wide prominence was the demonstrations that can enthral African judge Sa'id bin Jubair, an audience. around 700AD. Harry Nelson Pillsbury (see Of these, Blindfold Chess, Players of the romantic era Forgotten Heroes: Harry Nelson especially the playing of who excelled at blindfold chess Pillsbury , by Anil K.Anand in the AICCF Bulletin simultaneous blindfold games, is include Philidor, Morphy, , May 2005, p.19) perhaps the most amazing and Paulsen, Pillsbury, Reti, is attributed with the memory surely the most taxing to the Alekhine. -

The Reviled Art Stuart Rachels

The Reviled Art Stuart Rachels “If chess is an art, it is hardly treated as such in the United States. Imagine what it would be like if music were as little known or appreciated. Suppose no self-respecting university would offer credit courses in music, and the National Endowment for the Arts refused to pay for any of it. A few enthusiasts might compose sonatas, and study and admire one another’s efforts, but they would largely be ignored. Once in a while a Mozart might capture the public imagination, and like Bobby Fischer get written about in Newsweek. But the general attitude would be that, while this playing with sound might be clever, and a great passion for those who care about it, still in the end it signifies nothing very important.” —James Rachels1 Bragging and Whining When I was 11, I became the youngest chess master in American history. It was great fun. My picture was put on the cover of Chess Life; I appeared on Shelby Lyman’s nationally syndicated chess show; complete strangers asked me if I was a genius; I got compared to my idol, Bobby Fischer (who was not a master until he was 13); and I generally enjoyed the head-swelling experience of being treated like a king, as a kid among adults. When I wasn’t getting bullied at school, I felt special. And the fact that I was from Alabama, oozing a slow Southern drawl, must have increased my 2 mystique, since many northeastern players assumed that I lived on a farm, and who plays chess out there? In my teens, I had some wonderful experiences. -

“Blindfold King” GM Gareyev's Exhibition

1 JUNE 2018 Chess News and Chess History for Oklahoma GM Timur Gareyev in Tulsa FKB Memorial #2 Won By Advait Patel • and • In This Issue: “Blindfold King” GM • FKB Memorial Gareyev’s Exhibition • by Tom Braunlich Gareyev “Oklahoma’s Official Chess Blindfold Bulletin Covering Oklahoma Chess Simul The weekend of May 18-20 saw two big chess on a Regular Schedule Since 1982” • events in Tulsa: an impressive 7-player http://ocfchess.org IM Donaldson blindfold chess exhibition and lecture by GM Book Review Oklahoma Chess Timur Gareyev, the ‘blindfold king’, and the • nd Foundation 2 annual Frank K Berry Memorial tournament Plus Register Online for Free of traditional chess, in which GM Gareyev News Bites, played. Game of the Editor: Tom Braunlich Month, The events were sponsored by Harold Brown, Asst. Ed. Rebecca Rutledge st Puzzles, and organized by the OCF, with TD Jim Berry Published the 1 of each month. Top 25 List, and assitant Tom Braunlich. Send story submissions and Tournament This report covers both events. tournament reports, etc., by the Reports, 15th of the previous month to and more. For the clash between GM Gareyev and IM Patel, see the “Game of the Month” (page 15). mailto:[email protected] For other games from the tournament see the games section beginning page 8. ©2018 All rights reserved. 23 The Blindfold King Comes to Tulsa About 50 spectators came to the Tulsa Wyndham on Friday night to see GM Timur Gareyev — holder of the official world record for blindfold simultaneous chess play — take on seven Okie tournament players in exhibition play. -

Copyrighted Material

31_584049 bindex.qxd 7/29/05 9:09 PM Page 345 Index attack, 222–224, 316 • Numbers & Symbols • attacked square, 42 !! (double exclamation point), 272 Averbakh, Yuri ?? (double question mark), 272 Chess Endings: Essential Knowledge, 147 = (equal sign), 272 minority attack, 221 ! (exclamation point), 272 –/+ (minus/plus sign), 272 • B • + (plus sign), 272 +/– (plus/minus sign), 272 back rank mate, 124–125, 316 # (pound sign), 272 backward pawn, 59, 316 ? (question mark), 272 bad bishop, 316 1 ⁄2 (one-half fraction), 272 base, 62 BCA (British Chess Association), 317 BCF (British Chess Federation), 317 • A • beginner’s mistakes About Chess (Web site), 343 check, 50, 157 active move, 315 endgame, 147 adjournment, 315 opening, 193–194 adjudication, 315 scholar’s mate, 122–123 adjusting pieces, 315 tempo gains and losses, 50 Alburt, Lev (Comprehensive beginning of game (opening). See also Chess Course), 341 specific moves Alekhine, Alexander (chess player), analysis of, 196–200 179, 256, 308 attacks on opponent, 195–196 Alekhine’s Defense (opening), 209 beginner’s mistakes, 193–194 algebraic notation, 263, 316 centralization, 180–184 analog clock, 246 checkmate, 193, 194 Anand, Viswanathan (chess player), chess notation, 264–266 251, 312 definition, 11, 331 Anderssen, Adolf (chess player), development, 194–195 278–283, 310, 326COPYRIGHTEDdifferences MATERIAL in names, 200 annotation discussion among players, 200 cautions, 278 importance, 193 definition, 12, 316 king safety strategy, 53, 54 overview, 272 knight movements, 34–35 ape-man strategy, -

NVIDIA GTC: March 21, 2019 Reconnaissance Blind Chess (RBC

Reconnaissance Blind Chess (RBC): A Challenge Problem for Planning and Autonomy NVIDIA GTC: March 21, 2019 Casey Richardson, Ph.D. [email protected] Inventing the future of intelligent systems for our Nation Intelligent Systems Center 19 March 2019 2 AI & Decision-Making: What Intelligent Systems Do Perceive Decide Act Team Boston Dynamic’s “Physical Intelligence” demonstrations Intelligent Systems Center 19 March 2019 3 What Is Reconnaissance Blind Chess (RBC)? • Chess variant(s) where players: - Cannot see the opponent’s moves, pieces, or board position (blind) - Gain information about the ground truth board through active sensing actions (reconnaissance) • RBC adds the following elements to standard chess - Sensing (potentially noisy and multi-modality) - Incomplete information - Decision making under uncertainty - Joint decision / battle management and sensor management - Multiple, simultaneous, competing objectives 4 Why Did We Invent RBC? • RBC is a new reference/challenge problem for research in autonomy and intelligent systems - Emphasizes strategic and tactical decision making under uncertainty in a dynamic, adversarial environment • RBC provides an accessible challenge problem in fusion and resource management enabling open collaboration - Abstracts and incorporates the many common elements (e.g., value of information) in areas such as . Autonomy . Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) . Optimal Sensor Tasking for Disaster Relief scenarios - There is currently no common, unclassified, open experimentation -

Python-Chess Release 1.6.1

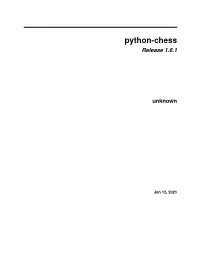

python-chess Release 1.6.1 unknown Jun 12, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 2 Installing 5 3 Documentation 7 4 Features 9 5 Selected projects 13 6 Acknowledgements 15 7 License 17 8 Contents 19 8.1 Core................................................... 19 8.2 PGN parsing and writing......................................... 36 8.3 Polyglot opening book reading...................................... 44 8.4 Gaviota endgame tablebase probing................................... 45 8.5 Syzygy endgame tablebase probing................................... 47 8.6 UCI/XBoard engine communication................................... 49 8.7 SVG rendering.............................................. 61 8.8 Variants.................................................. 63 8.9 Changelog for python-chess....................................... 65 9 Indices and tables 71 Index 73 i ii python-chess, Release 1.6.1 CONTENTS 1 python-chess, Release 1.6.1 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION python-chess is a chess library for Python, with move generation, move validation, and support for common formats. This is the Scholar’s mate in python-chess: >>> import chess >>> board= chess.Board() >>> board.legal_moves <LegalMoveGenerator at ... (Nh3, Nf3, Nc3, Na3, h3, g3, f3, e3, d3, c3, ...)> >>> chess.Move.from_uci("a8a1") in board.legal_moves False >>> board.push_san("e4") Move.from_uci('e2e4') >>> board.push_san("e5") Move.from_uci('e7e5') >>> board.push_san("Qh5") Move.from_uci('d1h5') >>> board.push_san("Nc6") Move.from_uci('b8c6') >>> board.push_san("Bc4") Move.from_uci('f1c4') >>> board.push_san("Nf6") Move.from_uci('g8f6') >>> board.push_san("Qxf7") Move.from_uci('h5f7') >>> board.is_checkmate() True >>> board Board('r1bqkb1r/pppp1Qpp/2n2n2/4p3/2B1P3/8/PPPP1PPP/RNB1K1NR b KQkq - 0 4') 3 python-chess, Release 1.6.1 4 Chapter 1. Introduction CHAPTER TWO INSTALLING Download and install the latest release: pip install chess 5 python-chess, Release 1.6.1 6 Chapter 2. -

Chess Snapshots from 1895-1972

Chess Snapshots from 1895-1972 Emanuel Lasker (1868-1941) World champion, defeating Steinitz in 1894. Lasker was 26 years old and Steinitz Akiba Rubinstein (1882-1961) - Endgame Specialist Alexander Alekhine (1892-1946) was 58 at the time. World Champion from 1927-1935 Held the title until 1921, when he lost to Jose Raul Capablanca. Rubinstein’s endgames displayed a clarity unlike and 1937-his death. • Flexible style nearly all the other great players in history up to that Alekhine was one of the most By the end of the 19th century, the principles of Wilhelm Steinitz were fast becoming accepted by the • Willing to play double edged positions that might have favored his opponent. time. In his prime he was one of the top few players brilliant attacking players of all time. top players of the day. A more scientific approach was now put into practice in which “positional” ideas Frequently, he would outplay his opponent during the ensuing complications. in the world. A 1912 world championship match He pursued Capablanca for a world were as important as the tactical themes that were frequently the primary consideration during the • Very long career: Finished first at the extremely strong New York International against the reigning world champion (Lasker) did not title match, and finally had his swashbuckling earlier years of competition. tournament of 1924 at age 55. In 1935 at age 66 finished third at the Moscow materialize due to Rubinsteins inability to obtain the chance in 1927. He was extremely International tournament without losing a single game. necessary funds demanded by Lasker.