The Reviled Art Stuart Rachels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recovering and Rendering Vital Blueprint for Counter Education At

Recovering and Rendering Vital clash that erupted between the staid, conservative Board of Trustees and the raucous experimental work and atti- Blueprint for Counter Education tudes put forth by students and faculty (the latter often- times more militant than the former). The full story of the at the California Institute of the Arts Institute during its frst few years requires (and deserves) an entire book,8 but lines from a 1970 letter by Maurice Paul Cronin Stein, founding Dean of the School of Critical Studies, written a few months before the frst students arrived on campus, gives an indication of the conficts and delecta- tions to come: “This is the most hectic place in the world at the moment and promises to become even more so. At heart of the California Institute of Arts’ campus is We seem to be testing some complex soap opera prop- a vast, monolithic concrete building, containing more osition about the durability of a marriage between the than a thousand rooms. Constructed on a sixty-acre site radical right and left liberals. My only way of adjusting to thirty-fve miles north of Los Angeles, it is centered in the situation is to shut my eyes, do my job, and hope for what at the end of the 1960s was the remote outpost the best.”9 of sun-scorched Valencia (a town “dreamed up by real estate developers to receive the urban sprawl which is • • • Los Angeles”),1 far from Hollywood, a town that was—for many students at the Institute—the belly of the beast. -

1999/6 Layout

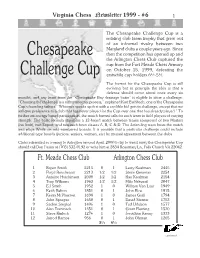

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

11 Triple Loyd

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS Jeff Coakley TRIPLE LOYDS: BLACK PIECES number 11 September 22, 2012 The “triple loyd” is a puzzle that appears every few weeks on The Puzzling Side of Chess. It is named after Sam Loyd, the American chess composer who published the prototype in 1866. In this column, we feature positions that include black pieces. A triple loyd is three puzzles in one. In each part, your task is to place the black king on the board.to achieve a certain goal. Triple Loyd 07 w________w áKdwdwdwd] àdwdwdwdw] ßwdwdw$wd] ÞdwdRdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdpdwd] Údwdwdwdw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. For triple loyds 1-6 and additional information on Sam Loyd, see columns 1 and 5 in the archives. As you probably noticed from the first puzzle, finding the stalemate (part B) can be easy if Black has any mobile pieces. The black king must be placed to take away their moves. Triple Loyd 08 w________w áwdwdBdwd] àdwdRdwdw] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdw0Ndwd] ÜdwdPhwdw] ÛwdwGwdwd] Údwdw$wdK] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. The next triple loyd sets a record of sorts. It contains thirty-one pieces. Only the black king is missing. Triple Loyd 09 w________w árhbdwdwH] àgpdpdw0w] ßqdp!w0B0] Þ0ndw0PdN] ÝPdw4Pdwd] ÜdRdPdwdP] Ûw)PdwGPd] ÚdwdwIwdR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

Weltenfern a Commented Selection of Some of My Works Containing 149 Originals

Weltenfern A commented selection of some of my works containing 149 originals by Siegfried Hornecker Dedicated to the memory of Dan Meinking and Milan Velimirovi ć who both encouraged me to write a book! Weltenfern : German for other-worldly , literally distant from the world , describing a person’s attitude In the opinion of the author the perfect state of mind to compose chess problems. - 1 - Index 1 – Weltenfern 2 – Index 3 – Legal Information 4 – Preface 6 – 20 ideas and themes 6 – Chapter One: A first walk in the park 8 – Chapter Two: Schachstrategie 9 – Chapter Three: An anticipated study 11 – Chapter Four: Sleepless nights, or how pain was turned into beauty 13 – Chapter Five: Knightmares 15 – Chapter Six: Saavedra 17 – Chapter Seven: Volpert, Zatulovskaya and an incredible pawn endgame 21 – Chapter Eight: My home is my castle, but I can’t castle 27 – Intermezzo: Orthodox problems 31 – Chapter Nine: Cooperation 35 – Chapter Ten: Flourish, Knightingale 38 – Chapter Eleven: Endgames 42 – Chapter Twelve: MatPlus 53 – Chapter 13: Problem Paradise and NONA 56 – Chapter 14: Knight Rush 62 – Chapter 15: An idea of symmetry and an Indian mystery 67 – Information: Logic and purity of aim (economy of aim) 72 – Chapter 16: Make the piece go away 77 – Chapter 17: Failure of the attack and the romantic chess as we knew it 82 – Chapter 18: Positional draw (what is it, anyway?) 86 – Chapter 19: Battle for the promotion 91 – Chapter 20: Book Ends 93 – Dessert: Heterodox problems 97 – Appendix: The simple things in life 148 – Epilogue 149 – Thanks 150 – Author index 152 – Bibliography 154 – License - 2 - Legal Information Partial reprint only with permission. -

Altogether Now in My Decades of Playing Sub-Optimal Chess, I Have

Altogether now In my decades of playing sub-optimal chess, I have been given several pieces of advice about how best to play simultaneous chess. I have faced several grandmasters over the board in simuls and tried to adopt these tips, but with very little success. In fact, no success. One suggestion was to tactically muddy the waters. The theory being if you play a closed positional game the GM (or whoever is giving the simul) will easily overcome you end in the end with their superior technique. On the other hand, although they are, of course, much better than you tactically if they have 20 odd other boards to focus on, effectively playing their moves at a rate akin to blitz, there is a chance they might slip up and give you some winning chances when faced with a messy position. This is fine in theory and may work well for those players stronger then myself who are adept at tactics but my record of my games shows a whopping nil points for me with this approach. In fact, I have found the opposite to be true. I am pleased to report that I have achieved a couple of draws from playing a completely blocked stagnant position. The key here has been to try to make the games last sufficiently long so that in the end then GM kindly offers you a draw in a desperate attempt to get his last bus home. Although loathsome this is when you want as many of those horrible creatures who play on when they are a rook and a bishop down with no compensation (or similar) to keep on playing against the GM. -

Of Kings and Pawns

OF KINGS AND PAWNS CHESS STRATEGY IN THE ENDGAME ERIC SCHILLER Universal Publishers Boca Raton • 2006 Of Kings and Pawns: Chess Strategy in the Endgame Copyright © 2006 Eric Schiller All rights reserved. Universal Publishers Boca Raton , Florida USA • 2006 ISBN: 1-58112-909-2 (paperback) ISBN: 1-58112-910-6 (ebook) Universal-Publishers.com Preface Endgames with just kings and pawns look simple but they are actually among the most complicated endgames to learn. This book contains 26 endgame positions in a unique format that gives you not only the starting position, but also a critical position you should use as a target. Your workout consists of looking at the starting position and seeing if you can figure out how you can reach the indicated target position. Although this hint makes solving the problems easier, there is still plenty of work for you to do. The positions have been chosen for their instructional value, and often combined many different themes. You’ll find examples of the horse race, the opposition, zugzwang, stalemate and the importance of escorting the pawn with the king marching in front, among others. When you start out in chess, king and pawn endings are not very important because usually there is a great material imbalance at the end of the game so one side is winning easily. However, as you advance through chess you’ll find that these endgame positions play a great role in determining the outcome of the game. It is critically important that you understand when a single pawn advantage or positional advantage will lead to a win and when it will merely wind up drawn with best play. -

I Make This Pledge to You Alone, the Castle Walls Protect Our Back That I Shall Serve Your Royal Throne

AMERA M. ANDERSEN Battlefield of Life “I make this pledge to you alone, The castle walls protect our back that I shall serve your royal throne. and Bishops plan for their attack; My silver sword, I gladly wield. a master plan that is concealed. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight times eight the battlefield. With knights upon their mighty steed For chess is but a game of life the front line pawns have vowed to bleed and I your Queen, a loving wife and neither Queen shall ever yield. shall guard my liege and raise my shield Squares eight times eight the battlefield. Squares eight time eight the battlefield.” Apathy Checkmate I set my moves up strategically, enemy kings are taken easily Knights move four spaces, in place of bishops east of me Communicate with pawns on a telepathic frequency Smash knights with mics in militant mental fights, it seems to be An everlasting battle on the 64-block geometric metal battlefield The sword of my rook, will shatter your feeble battle shield I witness a bishop that’ll wield his mystic sword And slaughter every player who inhabits my chessboard Knight to Queen’s three, I slice through MCs Seize the rook’s towers and the bishop’s ministries VISWANATHAN ANAND “Confidence is very important—even pretending to be confident. If you make a mistake but do not let your opponent see what you are thinking, then he may overlook the mistake.” Public Enemy Rebel Without A Pause No matter what the name we’re all the same Pieces in one big chess game GERALD ABRAHAMS “One way of looking at chess development is to regard it as a fight for freedom. -

Chess Strategies for Beginners II Top Books for Beginners Chess Thinking

Chess Strategies for Beginners II Stop making silly Moves! Learn Chess Strategies for Beginners to play better chess. Stop losing making dumb moves. "When you are lonely, when you feel yourself an alien in the world, play Chess. This will raise your spirits and be your counselor in war." Aristotle Learn chess strategies first at Chess Strategies for Beginners I. After that come back here. Chess Formation Strategy I show you now how to start your game. Before you start to play you should know where to place your pieces - know the right chess formation strategy. Where do you place your pawns, knights and bishops, when do you castle and what happens to the queen and the rooks. When should you attack? Or do you have to attack at all? Questions over questions. I will give you a rough idea now. Please study the following chess strategies for beginners carefully. Read the Guidelines: Chess Formation Strategy. WRITE YOUR REVIEW ASK QUESTIONS HERE! Top Books For Beginners For beginners I recommend Logical Chess - Move by Move by Chernev because it explains every move. Another good book is the Complete Idiot's Guide to Chess that received very good reviews. Chess Thinking Now try to get mentally into the real game and try to understand some of the following positions. Some are difficult to master, but don't worry, just repeat them the next day to get used to chess thinking. Your brain has to adjust, that's all there is to it. Win some Positions here! - Chess Puzzles Did you manage it all right? It is necessary that you understand the following basic chess strategies for beginners called - Endgames or Endings, using the heavy pieces.(queen and rook are called heavy pieces) Check them out now! Rook and Queen Endgames - Basic Chess Strategies How a Beginner plays Chess Replay the games of a beginner. -

A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague – Candidates Tournament 2020

A FEAST OF CHESS IN TIME OF PLAGUE CANDIDATES TOURNAMENT 2020 Part 1 — Yekaterinburg by Vladimir Tukmakov www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor Romain Edouard Assistant Editor Daniël Vanheirzeele Translator Izyaslav Koza Proofreader Bob Holliman Graphic Artist Philippe Tonnard Cover design Mieke Mertens Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2020 by Th inkers Publishing A Feast of Chess in Time of Plague. Candidates Tournament 2020. Part 1 — Yekaterinburg Copyright © 2020 Vladimir Tukmakov All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-94-9251-092-1 D/2020/13730/26 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Th inkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.thinkerspublishing.com TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO SYMBOLS 5 INTRODUCTION 7 PRELUDE 11 THE PLAY Round 1 21 Round 2 44 Round 3 61 Round 4 80 Round 5 94 Round 6 110 Round 7 127 Final — Round 8 141 UNEXPECTED CONCLUSION 143 INTERIM RESULTS 147 KEY TO SYMBOLS ! a good move ?a weak move !! an excellent move ?? a blunder !? an interesting move ?! a dubious move only move =equality unclear position with compensation for the sacrifi ced material White stands slightly better Black stands slightly better White has a serious advantage Black has a serious advantage +– White has a decisive advantage –+ Black has a decisive advantage with an attack with initiative with counterplay with the idea of better is worse is Nnovelty +check #mate INTRODUCTION In the middle of the last century tournament compilations were ex- tremely popular. -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

A Glimpse Into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015

Media Contact: Amanda Cook [email protected] 314-598-0544 A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015 July XX, 2014 (Saint Louis, MO) – From his earliest years as a child prodigy to becoming the only player ever to achieve a perfect score in the U.S. Chess Championships, from winning the World Championship in 1972 against Boris Spassky to living out a controversial retirement, Bobby Fischer stands as one of chess’s most complicated and compelling figures. A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer opens July 24, 2014, at the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) and will celebrate Fischer’s incredible career while examining his singular intellect. The show runs through June 7, 2015. “We are thrilled to showcase many never-before-seen artifacts that capture Fischer’s career in a unique way. Those who study chess will have the rare opportunity to learn from his notes and books while casual fans will enjoy exploring this superstar’s personal story,” said WCHOF Chief Curator Bobby Fischer, seen from above, Shannon Bailey. makes a move during the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup. Several of the rarest pieces on display are on generous loan from Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, owners of a a collection of material from Fischer’s own library that includes 320 books and 400 periodicals. These items supplement highlights from WCHOF’s permanent collection to create a spectacular show. Highlights from the exhibition: Furniture from the home of Fischer’s mentor Jack Collins, which