Technical Paper Quantitation of Carotenoids in Raw and Processed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altered Xanthophyll Compositions Adversely Affect Chlorophyll Accumulation and Nonphotochemical Quenching in Arabidopsis Mutants

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 95, pp. 13324–13329, October 1998 Plant Biology Altered xanthophyll compositions adversely affect chlorophyll accumulation and nonphotochemical quenching in Arabidopsis mutants BARRY J. POGSON*, KRISHNA K. NIYOGI†,OLLE BJO¨RKMAN‡, AND DEAN DELLAPENNA§¶ *Department of Plant Biology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-1601; †Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3102; ‡Department of Plant Biology, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Stanford, CA 94305-4101; and §Department of Biochemistry, University of Nevada, Reno, NV 89557-0014 Contributed by Olle Bjo¨rkman, September 4, 1998 ABSTRACT Collectively, the xanthophyll class of carote- thin, are enriched in the LHCs, where they contribute to noids perform a variety of critical roles in light harvesting assembly, light harvesting, and photoprotection (2–8). antenna assembly and function. The xanthophyll composition A summary of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway of higher of higher plant photosystems (lutein, violaxanthin, and neox- plants and relevant chemical structures is shown in Fig. 1. anthin) is remarkably conserved, suggesting important func- Lycopene is cyclized twice by the enzyme lycopene b-cyclase tional roles for each. We have taken a molecular genetic to form b-carotene. The two beta rings of b-carotene are approach in Arabidopsis toward defining the respective roles of subjected to identical hydroxylation reactions to yield zeaxan- individual xanthophylls in vivo by using a series of mutant thin, which in turn is epoxidated once to form antheraxanthin lines that selectively eliminate and substitute a range of and twice to form violaxanthin. Neoxanthin is derived from xanthophylls. The mutations, lut1 and lut2 (lut 5 lutein violaxanthin by an additional rearrangement (9). -

Identification of Distinct Ph- and Zeaxanthin-Dependent Quenching

RESEARCH ARTICLE Identification of distinct pH- and zeaxanthin-dependent quenching in LHCSR3 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Julianne M Troiano1†, Federico Perozeni2†, Raymundo Moya1, Luca Zuliani2, Kwangyrul Baek3, EonSeon Jin3, Stefano Cazzaniga2, Matteo Ballottari2*, Gabriela S Schlau-Cohen1* 1Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, United States; 2Department of Biotechnology, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; 3Department of Life Science, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea Abstract Under high light, oxygenic photosynthetic organisms avoid photodamage by thermally dissipating absorbed energy, which is called nonphotochemical quenching. In green algae, a chlorophyll and carotenoid-binding protein, light-harvesting complex stress-related (LHCSR3), detects excess energy via a pH drop and serves as a quenching site. Using a combined in vivo and in vitro approach, we investigated quenching within LHCSR3 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. In vitro two distinct quenching processes, individually controlled by pH and zeaxanthin, were identified within LHCSR3. The pH-dependent quenching was removed within a mutant LHCSR3 that lacks the residues that are protonated to sense the pH drop. Observation of quenching in zeaxanthin-enriched LHCSR3 even at neutral pH demonstrated zeaxanthin-dependent quenching, which also occurs in other light-harvesting complexes. Either pH- or zeaxanthin-dependent quenching prevented the formation of damaging reactive oxygen species, and thus the two *For correspondence: quenching processes may together provide different induction and recovery kinetics for [email protected] (MB); photoprotection in a changing environment. [email protected] (GSS-C) †These authors contributed equally to this work Competing interests: The Introduction authors declare that no Sunlight is the essential source of energy for most photosynthetic organisms, yet sunlight in excess competing interests exist. -

Identification of 1 Distinct Ph- and Zeaxanthin-Dependent Quenching in LHCSR3 from Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii

Identification of 1 distinct pH- and zeaxanthin-dependent quenching in LHCSR3 from chlamydomonas reinhardtii The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Troiano, Julianne M. et al. “Identification of 1 distinct pH- and zeaxanthin-dependent quenching in LHCSR3 from chlamydomonas reinhardtii.” eLife, 10 (January 2021): e60383 © 2021 The Author(s) As Published 10.7554/eLife.60383 Publisher eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/130449 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Detailed Terms https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ RESEARCH ARTICLE Identification of distinct pH- and zeaxanthin-dependent quenching in LHCSR3 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii Julianne M Troiano1†, Federico Perozeni2†, Raymundo Moya1, Luca Zuliani2, Kwangyrul Baek3, EonSeon Jin3, Stefano Cazzaniga2, Matteo Ballottari2*, Gabriela S Schlau-Cohen1* 1Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, United States; 2Department of Biotechnology, University of Verona, Verona, Italy; 3Department of Life Science, Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea Abstract Under high light, oxygenic photosynthetic organisms avoid photodamage by thermally dissipating absorbed energy, which is called nonphotochemical quenching. In green algae, a chlorophyll and carotenoid-binding protein, light-harvesting complex stress-related (LHCSR3), detects excess energy via a pH drop and serves as a quenching site. Using a combined in vivo and in vitro approach, we investigated quenching within LHCSR3 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. In vitro two distinct quenching processes, individually controlled by pH and zeaxanthin, were identified within LHCSR3. The pH-dependent quenching was removed within a mutant LHCSR3 that lacks the residues that are protonated to sense the pH drop. -

Genetic Modification of Tomato with the Tobacco Lycopene Β-Cyclase Gene Produces High Β-Carotene and Lycopene Fruit

Z. Naturforsch. 2016; 71(9-10)c: 295–301 Louise Ralley, Wolfgang Schucha, Paul D. Fraser and Peter M. Bramley* Genetic modification of tomato with the tobacco lycopene β-cyclase gene produces high β-carotene and lycopene fruit DOI 10.1515/znc-2016-0102 and alleviation of vitamin A deficiency by β-carotene, Received May 18, 2016; revised July 4, 2016; accepted July 6, 2016 which is pro-vitamin A [4]. Deficiency of vitamin A causes xerophthalmia, blindness and premature death, espe- Abstract: Transgenic Solanum lycopersicum plants cially in children aged 1–4 [5]. Since humans cannot expressing an additional copy of the lycopene β-cyclase synthesise carotenoids de novo, these health-promoting gene (LCYB) from Nicotiana tabacum, under the control compounds must be taken in sufficient quantities in the of the Arabidopsis polyubiquitin promoter (UBQ3), have diet. Consequently, increasing their levels in fruit and been generated. Expression of LCYB was increased some vegetables is beneficial to health. Tomato products are 10-fold in ripening fruit compared to vegetative tissues. the most common source of dietary lycopene. Although The ripe fruit showed an orange pigmentation, due to ripe tomato fruit contains β-carotene, the amount is rela- increased levels (up to 5-fold) of β-carotene, with negli- tively low [1]. Therefore, approaches to elevate β-carotene gible changes to other carotenoids, including lycopene. levels, with no reduction in lycopene, are a goal of Phenotypic changes in carotenoids were found in vegeta- plant breeders. One strategy that has been employed to tive tissues, but levels of biosynthetically related isopre- increase levels of health promoting carotenoids in fruits noids such as tocopherols, ubiquinone and plastoquinone and vegetables for human and animal consumption is were barely altered. -

Carotenoid Composition of Strawberry Tree (Arbutus Unedo L.) Fruits

Accepted Manuscript Carotenoid composition of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruits Raúl Delgado-Pelayo, Lourdes Gallardo-Guerrero, Dámaso Hornero-Méndez PII: S0308-8146(15)30273-9 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.11.135 Reference: FOCH 18476 To appear in: Food Chemistry Received Date: 25 May 2015 Revised Date: 21 November 2015 Accepted Date: 28 November 2015 Please cite this article as: Delgado-Pelayo, R., Gallardo-Guerrero, L., Hornero-Méndez, D., Carotenoid composition of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruits, Food Chemistry (2015), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem. 2015.11.135 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Carotenoid composition of strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo L.) fruits. Raúl Delgado-Pelayo, Lourdes Gallardo-Guerrero, Dámaso Hornero-Méndez* Group of Chemistry and Biochemistry of Pigments. Food Phytochemistry Department. Instituto de la Grasa (CSIC). Campus Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Ctra. de Utrera km. 1. 41013 - Sevilla (Spain). * Corresponding author. Telephone: +34 954611550; Fax: +34 954616790; e-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract The carotenoid composition of strawberry tree (A. unedo) fruits has been characterised in detail and quantified for the first time. According to the total carotenoid content (over 340 µg/g dw), mature strawberry tree berries can be classified as fruits with very high carotenoid content (> 20 µg/g dw). -

Pigment Palette by Dr

Tree Leaf Color Series WSFNR08-34 Sept. 2008 Pigment Palette by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Autumn tree colors grace our landscapes. The palette of potential colors is as diverse as the natural world. The climate-induced senescence process that trees use to pass into their Winter rest period can present many colors to the eye. The colored pigments produced by trees can be generally divided into the green drapes of tree life, bright oil paints, subtle water colors, and sullen earth tones. Unveiling Overpowering greens of summer foliage come from chlorophyll pigments. Green colors can hide and dilute other colors. As chlorophyll contents decline in fall, other pigments are revealed or produced in tree leaves. As different pigments are fading, being produced, or changing inside leaves, a host of dynamic color changes result. Taken altogether, the various coloring agents can yield an almost infinite combination of leaf colors. The primary colorants of fall tree leaves are carotenoid and flavonoid pigments mixed over a variable brown background. There are many tree colors. The bright, long lasting oil paints-like colors are carotene pigments produc- ing intense red, orange, and yellow. A chemical associate of the carotenes are xanthophylls which produce yellow and tan colors. The short-lived, highly variable watercolor-like colors are anthocyanin pigments produc- ing soft red, pink, purple and blue. Tannins are common water soluble colorants that produce medium and dark browns. The base color of tree leaf components are light brown. In some tree leaves there are pale cream colors and blueing agents which impact color expression. -

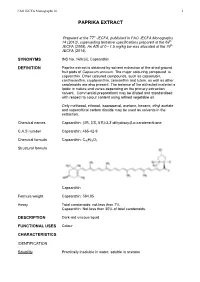

Paprika Extract (Tentative)

PAPRIKA EXTRACT (TENTATIVE) New tentative specifications prepared at the 69th JECFA (2008), published in FAO JECFA Monographs 5 (2008). No ADI was allocated at the 69th JECFA (2008). Information required on batches of commercially available products: • analytical data on composition • levels of capsaicinoids • levels of arsenic SYNONYMS INS No. 160c, Capsanthin, Capsorubin DEFINITION Paprika extract is obtained by solvent extraction of the dried ground fruit pods of Capsicum annuum. The major colouring compounds are capsanthin and capsorubin. Other coloured compounds, such as other carotenoids are also present. The balance of the extracted material is lipidic in nature and varies depending on the primary extraction solvent. Commercial preparations may be diluted and standardised with respect to colour content using refined vegetable oil. Only methanol, ethanol, 2-propanol, acetone, hexane, ethyl acetate and supercritical carbon dioxide may be used as solvents in the extraction. Chemical names Capsanthin: (3R, 3’S, 5’R)-3,3’-dihydroxy-β,κ-carotene-6-one Capsorubin: (3S, 3’S, 5R, 5’R)-3,3’-dihydroxy-κ,κ-carotene-6,6’- dione C.A.S number Capsanthin: 465-42-9 Capsorubin: 470-38-2 Chemical formula Capsanthin: C40H56O3 Capsorubin: C40H56O4 Structural formula Capsanthin Capsorubin Formula weight Capsanthin: 584.85 Capsorubin: 600.85 Assay Total carotenoids: not less than declared. Capsanthin/capsorubin: Not less than 30% of total carotenoids. DESCRIPTION Dark-red viscous liquid FUNCTIONAL USE Colour CHARACTERISTICS IDENTIFICATION Solubility Practically insoluble in water, soluble in acetone Spectrophotometry Maximum absorption in acetone at about 462 nm and in hexane at about 470 nm. Colour reaction To one drop of sample add 2-3 drops of chloroform and one drop of sulfuric acid. -

OXIDATIVE STRESS in ALGAE: METHOD DEVELOPMENT and EFFECTS of TEMPERATURE on ANTIOXIDANT NUCLEAR SIGNALING COMPOUNDS Md Noman Siddiqui Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Theses Theses and Dissertations Spring 2014 OXIDATIVE STRESS IN ALGAE: METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND EFFECTS OF TEMPERATURE ON ANTIOXIDANT NUCLEAR SIGNALING COMPOUNDS Md Noman Siddiqui Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons Recommended Citation Siddiqui, Md Noman, "OXIDATIVE STRESS IN ALGAE: METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND EFFECTS OF TEMPERATURE ON ANTIOXIDANT NUCLEAR SIGNALING COMPOUNDS" (2014). Open Access Theses. 256. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_theses/256 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised/) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By MD NOMAN SIDDIQUI Entitled OXIDATIVE STRESS IN ALGAE: METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND EFFECTS OF TEMPERATURE ON ANTIOXIADANT NUCLEAR SIGNALING COMPOUNDS Master of Science For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: PAUL BROWN REUBEN GOFORTH THOMAS HOOK To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the 7KHVLV'LVVHUWDWLRQ$JUHHPHQW 3XEOLFDWLRQ'HOD\DQGCHUWLILFDWLRQDisclaimer (Graduate School Form ), this thesis/dissertation DGKHUHVWRWKHSURYLVLRQVRIPurdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. PAUL BROWN Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________ -

Organic Chemistry LD Synthesis and Purification of Organic Chemistry Compounds Column Chromatography As a Purification Process Leaflets C2.4.4.1

Organic Chemistry LD Synthesis and purification of organic Chemistry compounds Column chromatography as a purification process Leaflets C2.4.4.1 Separation of a leaf extract by column chromatography Aims of the experiment To produce a leaf extract. To demonstrate column chromatography as a method for separating substances according to their adsorption properties. To understand the separation principle of column chromatography using silica gel as the stationary phase. To explain the order of elution of various leaf pigments based on their molecular structure. To understand the structural associations between various classes of leaf pigments. Principles sorbed (they adhere to it) or desorbed (they return to the solution). Substances with a high affinity to the stationary Column chromatography is a frequently used method for phase spend on average a longer period of time in the ad- separating mixtures of substances in the laboratory. The sorbed state and less time in the solution. Therefore they substances are isolated based on their adhesion properties. It pass more slowly through the column than substances with a functions according to the same principle as other chromato- lower affinity to the stationary phase. graphic methods, but in contrast to these, it is used less for With column chromatography, the stationary phase is located identification and more for the separation and purification of in a cylindrical tube with a discharge tap on the underside. substances. The mobile phase trickles through the stationary phase by The substances to be separated are transported on a mobile gravitational force or is pumped through the stationary phase phase (solvent mixture) through a stationary phase (in this using compressed air (Flash chromatography). -

Paprika Extract

PAPRIKA EXTRACT Prepared at the 77th JECFA, published in FAO JECFA Monographs 14 (2013), superseding tentative specifications prepared at the 69th JECFA (2008). An ADI of 0 - 1.5 mg/kg bw was allocated at the 79th JECFA (2014). SYNONYMS INS No. 160c(ii), Capsanthin DEFINITION Paprika extract is obtained by solvent extraction of the dried ground fruit pods of Capsicum annuum. The major colouring compound is capsanthin. Other coloured compounds, such as capsorubin, canthaxanthin, cryptoxanthin, zeaxanthin and lutein, as well as other carotenoids are also present. The balance of the extracted material is lipidic in nature and varies depending on the primary extraction solvent. Commercial preparations may be diluted and standardised with respect to colour content using refined vegetable oil. Only methanol, ethanol, isopropanol, acetone, hexane, ethyl acetate and supercritical carbon dioxide may be used as solvents in the extraction. Chemical names Capsanthin: (3R, 3’S, 5’R)-3,3’-dihydroxy-β,κ-carotene-6-one C.A.S number Capsanthin: 465-42-9 Chemical formula Capsanthin: C40H56O3 Structural formula Capsanthin Formula weight Capsanthin: 584.85 Assay Total carotenoids: not less than 7% Capsanthin: Not less than 30% of total carotenoids. DESCRIPTION Dark-red viscous liquid FUNCTIONAL USES Colour CHARACTERISTICS IDENTIFICATION Solubility Practically insoluble in water, soluble in acetone Spectrophotometry Maximum absorption in acetone at about 462 nm and in hexane at about 470 nm. Colour reaction To one drop of sample add 2-3 drops of chloroform and one drop of sulfuric acid. A deep blue colour is produced. High performance liquid Passes test. chromatography (HPLC) See Method of assay, Capsanthin PURITY Residua l solvents Acetone Ethanol Ethyl acetate Not more than 50 mg/kg, singly or in Hexane combination Isopropanol Methanol See description under TESTS Capsaicinoids Not more than 200 mg/kg See description under TESTS Arsenic (Vol. -

Characterization of the Role of the Neoxanthin Synthase Gene Boanxs in Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Chinese Kale

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Characterization of the Role of the Neoxanthin Synthase Gene BoaNXS in Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Chinese Kale Yue Jian 1,2,†, Chenlu Zhang 1,†, Yating Wang 1,†, Zhiqing Li 1, Jing Chen 1, Wenting Zhou 1, Wenli Huang 1, Min Jiang 1, Hao Zheng 1, Mengyao Li 1 , Huiying Miao 2, Fen Zhang 1, Huanxiu Li 1, Qiaomei Wang 2,* and Bo Sun 1,* 1 College of Horticulture, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130, China; [email protected] (Y.J.); [email protected] (C.Z.); [email protected] (Y.W.); [email protected] (Z.L.); [email protected] (J.C.); [email protected] (W.Z.); [email protected] (W.H.); [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (H.Z.); [email protected] (M.L.); [email protected] (F.Z.); [email protected] (H.L.) 2 Department of Horticulture, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (Q.W.); [email protected] (B.S.); Tel.: +86-571-85909333 (Q.W.); +86-28-86291840 (B.S.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Chinese kale (Brassica oleracea var. alboglabra) is rich in carotenoids, and neoxanthin is one of the most important carotenoids in Chinese kale. In this study, the function of the neoxanthin synthase gene (BoaNXS) in Chinese kale was investigated. BoaNXS, which had a 699-bp coding sequence, was cloned from the white flower cultivar of Chinese kale and was expressed in all developmental stages and organs of Chinese kale; its expression was highest in young seeds. -

Petition to Include Synthetic Crystalline LYCOPENE at 7 CFR 205.605

Petition to Include Synthetic Crystalline LYCOPENE at 7 CFR 205.605 Item A This petition seeks inclusion of Synthetic Crystalline LYCOPENE on the National List as a non-agricultural (non-organic) substance allowed in or on processed products labeled as “organic” or “made with organic (specified ingredients),” at §205.605(b). Item B 1. The substance‟s chemical or material common name. Lycopene is a naturally occurring aliphatic hydrocarbon of the carotenoid class. Lycopene is the most abundant carotenoid in ripe tomatoes and comprises 80-90% of the total pigment. Lycopene contains thirteen double bonds. The all-trans isomer is predominant in tomatoes and other natural sources. Storage, cooking, food processing, and exposure to light may result in some isomerization of the all-trans form to various cis forms including the 5-cis, 9-cis, 13-cis, and 15- cis forms. Synthetic crystalline lycopene is predominantly the all trans-lycopene (>70%) with some 5-cis- lycopene and other cis isomers. Other chemical names for lycopene are ψ,ψ-carotene and (all-E)-all-trans-lycopene. It is commonly known as all-trans-lycopene. The systematic name for the all-trans-lycopene is (all- E)-2, 6, 10, 14, 19, 23, 27, 31-octamethyl-2,6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 30- dotricaconta-tridecaene. 2a. The name and address of the manufacturer/producer of the substance. Synthetic crystalline lycopene is produced by: BASF SE Carl-Bosch-Straße 38 67056 Ludwigshafen/Germany 2b. The name, address and telephone number and other contact information of the petitioner. International Formula Council 1100 Johnson Ferry Road NE, Suite 300 Atlanta, GA 30342 Contact: Mardi Mountford, Executive Vice President Phone: (678) 303-3027 Email: [email protected] Petition to Include Synthetic Crystalline LYCOPENE at 7 CFR 205.605 3.