Torque, Center of Mass, and Moment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane Michael Koken [email protected]

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Honors Research Projects College Fall 2017 The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane Michael Koken [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Aerospace Engineering Commons, Aviation Commons, Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons, Mechanical Engineering Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Koken, Michael, "The Experimental Determination of the Moment of Inertia of a Model Airplane" (2017). Honors Research Projects. 585. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/585 This Honors Research Project is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 2017 THE EXPERIMENTAL DETERMINATION OF A MODEL AIRPLANE KOKEN, MICHAEL THE UNIVERSITY OF AKRON Honors Project TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................ -

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

Pierre Simon Laplace - Biography Paper

Pierre Simon Laplace - Biography Paper MATH 4010 Melissa R. Moore University of Colorado- Denver April 1, 2008 2 Many people contributed to the scientific fields of mathematics, physics, chemistry and astronomy. According to Gillispie (1997), Pierre Simon Laplace was the most influential scientist in all history, (p.vii). Laplace helped form the modern scientific disciplines. His techniques are used diligently by engineers, mathematicians and physicists. His diverse collection of work ranged in all fields but began in mathematics. Laplace was born in Normandy in 1749. His father, Pierre, was a syndic of a parish and his mother, Marie-Anne, was from a family of farmers. Many accounts refer to Laplace as a peasant. While it was not exactly known the profession of his Uncle Louis, priest, mathematician or teacher, speculations implied he was an educated man. In 1756, Laplace enrolled at the Beaumont-en-Auge, a secondary school run the Benedictine order. He studied there until the age of sixteen. The nest step of education led to either the army or the church. His father intended him for ecclesiastical vocation, according to Gillispie (1997 p.3). In 1766, Laplace went to the University of Caen to begin preparation for a career in the church, according to Katz (1998 p.609). Cristophe Gadbled and Pierre Le Canu taught Laplace mathematics, which in turn showed him his talents. In 1768, Laplace left for Paris to pursue mathematics further. Le Canu gave Laplace a letter of recommendation to d’Alembert, according to Gillispie (1997 p.3). Allegedly d’Alembert gave Laplace a problem which he solved immediately. -

Magnetism, Angular Momentum, and Spin

Chapter 19 Magnetism, Angular Momentum, and Spin P. J. Grandinetti Chem. 4300 P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 19: Magnetism, Angular Momentum, and Spin In 1820 Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that electric current produces a magnetic field that deflects compass needle from magnetic north, establishing first direct connection between fields of electricity and magnetism. P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 19: Magnetism, Angular Momentum, and Spin Biot-Savart Law Jean-Baptiste Biot and Félix Savart worked out that magnetic field, B⃗, produced at distance r away from section of wire of length dl carrying steady current I is 휇 I d⃗l × ⃗r dB⃗ = 0 Biot-Savart law 4휋 r3 Direction of magnetic field vector is given by “right-hand” rule: if you point thumb of your right hand along direction of current then your fingers will curl in direction of magnetic field. current P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 19: Magnetism, Angular Momentum, and Spin Microscopic Origins of Magnetism Shortly after Biot and Savart, Ampére suggested that magnetism in matter arises from a multitude of ring currents circulating at atomic and molecular scale. André-Marie Ampére 1775 - 1836 P. J. Grandinetti Chapter 19: Magnetism, Angular Momentum, and Spin Magnetic dipole moment from current loop Current flowing in flat loop of wire with area A will generate magnetic field magnetic which, at distance much larger than radius, r, appears identical to field dipole produced by point magnetic dipole with strength of radius 휇 = | ⃗휇| = I ⋅ A current Example What is magnetic dipole moment induced by e* in circular orbit of radius r with linear velocity v? * 휋 Solution: For e with linear velocity of v the time for one orbit is torbit = 2 r_v. -

Position Management System Online Subject Area

USDA, NATIONAL FINANCE CENTER INSIGHT ENTERPRISE REPORTING Business Intelligence Delivered Insight Quick Reference | Position Management System Online Subject Area What is Position Management System Online (PMSO)? • This Subject Area provides snapshots in time of organization position listings including active (filled and vacant), inactive, and deleted positions. • Position data includes a Master Record, containing basic position data such as grade, pay plan, or occupational series code. • The Master Record is linked to one or more Individual Positions containing organizational structure code, duty station code, and accounting station code data. History • The most recent daily snapshot is available during a given pay period until BEAR runs. • Bi-Weekly snapshots date back to Pay Period 1 of 2014. Data Refresh* Position Management System Online Common Reports Daily • Provides daily results of individual position information, HR Area Report Name Load which changes on a daily basis. Bi-Weekly Organization • Position Daily for current pay and Position Organization with period/ Bi-Weekly • Provides the latest record regardless of previous changes Management PII (PMSO) for historical pay that occur to the data during a given pay period. periods *View the Insight Data Refresh Report to determine the most recent date of refresh Reminder: In all PMSO reports, users should make sure to include: • An Organization filter • PMSO Key elements from the Master Record folder • SSNO element from the Incumbent Employee folder • A time filter from the Snapshot Time folder 1 USDA, NATIONAL FINANCE CENTER INSIGHT ENTERPRISE REPORTING Business Intelligence Delivered Daily Calendar Filters Bi-Weekly Calendar Filters There are three time options when running a bi-weekly There are two ways to pull the most recent daily data in a PMSO report: PMSO report: 1. -

Chapters, in This Chapter We Present Methods Thatare Not Yet Employed by Industrial Robots, Except in an Extremely Simplifiedway

C H A P T E R 11 Force control of manipulators 11.1 INTRODUCTION 11.2 APPLICATION OF INDUSTRIAL ROBOTS TO ASSEMBLY TASKS 11.3 A FRAMEWORK FOR CONTROL IN PARTIALLY CONSTRAINED TASKS 11.4 THE HYBRID POSITION/FORCE CONTROL PROBLEM 11.5 FORCE CONTROL OFA MASS—SPRING SYSTEM 11.6 THE HYBRID POSITION/FORCE CONTROL SCHEME 11.7 CURRENT INDUSTRIAL-ROBOT CONTROL SCHEMES 11.1 INTRODUCTION Positioncontrol is appropriate when a manipulator is followinga trajectory through space, but when any contact is made between the end-effector and the manipulator's environment, mere position control might not suffice. Considera manipulator washing a window with a sponge. The compliance of thesponge might make it possible to regulate the force applied to the window by controlling the position of the end-effector relative to the glass. If the sponge isvery compliant or the position of the glass is known very accurately, this technique could work quite well. If, however, the stiffness of the end-effector, tool, or environment is high, it becomes increasingly difficult to perform operations in which the manipulator presses against a surface. Instead of washing with a sponge, imagine that the manipulator is scraping paint off a glass surface, usinga rigid scraping tool. If there is any uncertainty in the position of the glass surfaceor any error in the position of the manipulator, this task would become impossible. Either the glass would be broken, or the manipulator would wave the scraping toolover the glass with no contact taking place. In both the washing and scraping tasks, it would bemore reasonable not to specify the position of the plane of the glass, but rather to specifya force that is to be maintained normal to the surface. -

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM and ROTATIONS

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND ROTATIONS In classical mechanics the total angular momentum L~ of an isolated system about any …xed point is conserved. The existence of a conserved vector L~ associated with such a system is itself a consequence of the fact that the associated Hamiltonian (or Lagrangian) is invariant under rotations, i.e., if the coordinates and momenta of the entire system are rotated “rigidly” about some point, the energy of the system is unchanged and, more importantly, is the same function of the dynamical variables as it was before the rotation. Such a circumstance would not apply, e.g., to a system lying in an externally imposed gravitational …eld pointing in some speci…c direction. Thus, the invariance of an isolated system under rotations ultimately arises from the fact that, in the absence of external …elds of this sort, space is isotropic; it behaves the same way in all directions. Not surprisingly, therefore, in quantum mechanics the individual Cartesian com- ponents Li of the total angular momentum operator L~ of an isolated system are also constants of the motion. The di¤erent components of L~ are not, however, compatible quantum observables. Indeed, as we will see the operators representing the components of angular momentum along di¤erent directions do not generally commute with one an- other. Thus, the vector operator L~ is not, strictly speaking, an observable, since it does not have a complete basis of eigenstates (which would have to be simultaneous eigenstates of all of its non-commuting components). This lack of commutivity often seems, at …rst encounter, as somewhat of a nuisance but, in fact, it intimately re‡ects the underlying structure of the three dimensional space in which we are immersed, and has its source in the fact that rotations in three dimensions about di¤erent axes do not commute with one another. -

Position, Velocity, and Acceleration

Position,Position, Velocity,Velocity, andand AccelerationAcceleration Mr.Mr. MiehlMiehl www.tesd.net/miehlwww.tesd.net/miehl [email protected]@tesd.net Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration Velocity is the rate of change of position with respect to time. ΔD Velocity = ΔT Acceleration is the rate of change of velocity with respect to time. ΔV Acceleration = ΔT Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration Warning: Professional driver, do not attempt! When you’re driving your car… Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration squeeeeek! …and you jam on the brakes… Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration …and you feel the car slowing down… Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration …what you are really feeling… Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration …is actually acceleration. Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration I felt that acceleration. Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration How do you find a function that describes a physical event? Steps for Modeling Physical Data 1) Perform an experiment. 2) Collect and graph data. 3) Decide what type of curve fits the data. 4) Use statistics to determine the equation of the curve. Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration A crab is crawling along the edge of your desk. Its location (in feet) at time t (in seconds) is given by P (t ) = t 2 + t. a) Where is the crab after 2 seconds? b) How fast is it moving at that instant (2 seconds)? Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration A crab is crawling along the edge of your desk. Its location (in feet) at time t (in seconds) is given by P (t ) = t 2 + t. a) Where is the crab after 2 seconds? 2 P()22=+ () ( 2) P()26= feet Position,Position, VelocityVelocity && AccelerationAcceleration A crab is crawling along the edge of your desk. -

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions 3.1 The Important Stuff 3.1.1 Position In three dimensions, the location of a particle is specified by its location vector, r: r = xi + yj + zk (3.1) If during a time interval ∆t the position vector of the particle changes from r1 to r2, the displacement ∆r for that time interval is ∆r = r1 − r2 (3.2) = (x2 − x1)i +(y2 − y1)j +(z2 − z1)k (3.3) 3.1.2 Velocity If a particle moves through a displacement ∆r in a time interval ∆t then its average velocity for that interval is ∆r ∆x ∆y ∆z v = = i + j + k (3.4) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t As before, a more interesting quantity is the instantaneous velocity v, which is the limit of the average velocity when we shrink the time interval ∆t to zero. It is the time derivative of the position vector r: dr v = (3.5) dt d = (xi + yj + zk) (3.6) dt dx dy dz = i + j + k (3.7) dt dt dt can be written: v = vxi + vyj + vzk (3.8) 51 52 CHAPTER 3. MOTION IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS where dx dy dz v = v = v = (3.9) x dt y dt z dt The instantaneous velocity v of a particle is always tangent to the path of the particle. 3.1.3 Acceleration If a particle’s velocity changes by ∆v in a time period ∆t, the average acceleration a for that period is ∆v ∆v ∆v ∆v a = = x i + y j + z k (3.10) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t but a much more interesting quantity is the result of shrinking the period ∆t to zero, which gives us the instantaneous acceleration, a. -

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2 February 15, 2006 . DRAFT Cambridge-MIT Institute Multidisciplinary Design Project This Dictionary/Glossary of Engineering terms has been compiled to compliment the work developed as part of the Multi-disciplinary Design Project (MDP), which is a programme to develop teaching material and kits to aid the running of mechtronics projects in Universities and Schools. The project is being carried out with support from the Cambridge-MIT Institute undergraduate teaching programe. For more information about the project please visit the MDP website at http://www-mdp.eng.cam.ac.uk or contact Dr. Peter Long Prof. Alex Slocum Cambridge University Engineering Department Massachusetts Institute of Technology Trumpington Street, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Cambridge. Cambridge MA 02139-4307 CB2 1PZ. USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel: +44 (0) 1223 332779 tel: +1 617 253 0012 For information about the CMI initiative please see Cambridge-MIT Institute website :- http://www.cambridge-mit.org CMI CMI, University of Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology 10 Miller’s Yard, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Mill Lane, Cambridge MA 02139-4307 Cambridge. CB2 1RQ. USA tel: +44 (0) 1223 327207 tel. +1 617 253 7732 fax: +44 (0) 1223 765891 fax. +1 617 258 8539 . DRAFT 2 CMI-MDP Programme 1 Introduction This dictionary/glossary has not been developed as a definative work but as a useful reference book for engi- neering students to search when looking for the meaning of a word/phrase. It has been compiled from a number of existing glossaries together with a number of local additions. -

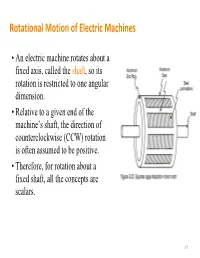

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Rotational Motion of Electric Machines • An electric machine rotates about a fixed axis, called the shaft, so its rotation is restricted to one angular dimension. • Relative to a given end of the machine’s shaft, the direction of counterclockwise (CCW) rotation is often assumed to be positive. • Therefore, for rotation about a fixed shaft, all the concepts are scalars. 17 Angular Position, Velocity and Acceleration • Angular position – The angle at which an object is oriented, measured from some arbitrary reference point – Unit: rad or deg – Analogy of the linear concept • Angular acceleration =d/dt of distance along a line. – The rate of change in angular • Angular velocity =d/dt velocity with respect to time – The rate of change in angular – Unit: rad/s2 position with respect to time • and >0 if the rotation is CCW – Unit: rad/s or r/min (revolutions • >0 if the absolute angular per minute or rpm for short) velocity is increasing in the CCW – Analogy of the concept of direction or decreasing in the velocity on a straight line. CW direction 18 Moment of Inertia (or Inertia) • Inertia depends on the mass and shape of the object (unit: kgm2) • A complex shape can be broken up into 2 or more of simple shapes Definition Two useful formulas mL2 m J J() RRRR22 12 3 1212 m 22 JRR()12 2 19 Torque and Change in Speed • Torque is equal to the product of the force and the perpendicular distance between the axis of rotation and the point of application of the force. T=Fr (Nm) T=0 T T=Fr • Newton’s Law of Rotation: Describes the relationship between the total torque applied to an object and its resulting angular acceleration. -

Finite Element Model Calibration of an Instrumented Thirteen-Story Steel Moment Frame Building in South San Fernando Valley, California

Finite Element Model Calibration of An Instrumented Thirteen-story Steel Moment Frame Building in South San Fernando Valley, California By Erol Kalkan Disclamer The finite element model incuding its executable file are provided by the copyright holder "as is" and any express or implied warranties, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose are disclaimed. In no event shall the copyright owner be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, exemplary, or consequential damages (including, but not limited to, procurement of substitute goods or services; loss of use, data, or profits; or business interruption) however caused and on any theory of liability, whether in contract, strict liability, or tort (including negligence or otherwise) arising in any way out of the use of this software, even if advised of the possibility of such damage. Acknowledgments Ground motions were recorded at a station owned and maintained by the California Geological Survey (CGS). Data can be downloaded from CESMD Virtual Data Center at: http://www.strongmotioncenter.org/cgi-bin/CESMD/StaEvent.pl?stacode=CE24567. Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 OpenSEES Model ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Calibration of OpenSEES Model to Observed Response