Rotational Motion of Electric Machines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Robert Katz Publications Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy 1-1958 Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) Henry Semat City College of New York Robert Katz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz Part of the Physics Commons Semat, Henry and Katz, Robert, "Physics, Chapter 11: Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body)" (1958). Robert Katz Publications. 141. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/physicskatz/141 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Research Papers in Physics and Astronomy at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Katz Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 11 Rotational Motion (The Dynamics of a Rigid Body) 11-1 Motion about a Fixed Axis The motion of the flywheel of an engine and of a pulley on its axle are examples of an important type of motion of a rigid body, that of the motion of rotation about a fixed axis. Consider the motion of a uniform disk rotat ing about a fixed axis passing through its center of gravity C perpendicular to the face of the disk, as shown in Figure 11-1. The motion of this disk may be de scribed in terms of the motions of each of its individual particles, but a better way to describe the motion is in terms of the angle through which the disk rotates. -

Influence of Angular Velocity of Pedaling on the Accuracy of The

Research article 2018-04-10 - Rev08 Influence of Angular Velocity of Pedaling on the Accuracy of the Measurement of Cyclist Power Abstract Almost all cycling power meters currently available on the The miscalculation may be—even significantly—greater than we market are positioned on rotating parts of the bicycle (pedals, found in our study, for the following reasons: crank arms, spider, bottom bracket/hub) and, regardless of • the test was limited to only 5 cyclists: there is no technical and construction differences, all calculate power on doubt other cyclists may have styles of pedaling with the basis of two physical quantities: torque and angular velocity greater variations of angular velocity; (or rotational speed – cadence). Both these measures vary only 2 indoor trainer models were considered: other during the 360 degrees of each revolution. • models may produce greater errors; The torque / force value is usually measured many times during slopes greater than 5% (the only value tested) may each rotation, while the angular velocity variation is commonly • lead to less uniform rotations and consequently neglected, considering only its average value for each greater errors. revolution (cadence). It should be noted that the error observed in this analysis This, however, introduces an unpredictable error into the power occurs because to measure power the power meter considers calculation. To use the average value of angular velocity means the average angular velocity of each rotation. In power meters to consider each pedal revolution as perfectly smooth and that use this type of calculation, this error must therefore be uniform: but this type of pedal revolution does not exist in added to the accuracy stated by the manufacturer. -

Basement Flood Mitigation

1 Mitigation refers to measures taken now to reduce losses in the future. How can homeowners and renters protect themselves and their property from a devastating loss? 2 There are a range of possible causes for basement flooding and some potential remedies. Many of these low-cost options can be factored into a family’s budget and accomplished over the several months that precede storm season. 3 There are four ways water gets into your basement: Through the drainage system, known as the sump. Backing up through the sewer lines under the house. Seeping through cracks in the walls and floor. Through windows and doors, called overland flooding. 4 Gutters can play a huge role in keeping basements dry and foundations stable. Water damage caused by clogged gutters can be severe. Install gutters and downspouts. Repair them as the need arises. Keep them free of debris. 5 Channel and disperse water away from the home by lengthening the run of downspouts with rigid or flexible extensions. Prevent interior intrusion through windows and replace weather stripping as needed. 6 Many varieties of sturdy window well covers are available, simple to install and hinged for easy access. Wells should be constructed with gravel bottoms to promote drainage. Remove organic growth to permit sunlight and ventilation. 7 Berms and barriers can help water slope away from the home. The berm’s slope should be about 1 inch per foot and extend for at least 10 feet. It is important to note permits are required any time a homeowner alters the elevation of the property. -

Simple Harmonic Motion

[SHIVOK SP211] October 30, 2015 CH 15 Simple Harmonic Motion I. Oscillatory motion A. Motion which is periodic in time, that is, motion that repeats itself in time. B. Examples: 1. Power line oscillates when the wind blows past it 2. Earthquake oscillations move buildings C. Sometimes the oscillations are so severe, that the system exhibiting oscillations break apart. 1. Tacoma Narrows Bridge Collapse "Gallopin' Gertie" a) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j‐zczJXSxnw II. Simple Harmonic Motion A. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=__2YND93ofE Watch the video in your spare time. This professor is my teaching Idol. B. In the figure below snapshots of a simple oscillatory system is shown. A particle repeatedly moves back and forth about the point x=0. Page 1 [SHIVOK SP211] October 30, 2015 C. The time taken for one complete oscillation is the period, T. In the time of one T, the system travels from x=+x , to –x , and then back to m m its original position x . m D. The velocity vector arrows are scaled to indicate the magnitude of the speed of the system at different times. At x=±x , the velocity is m zero. E. Frequency of oscillation is the number of oscillations that are completed in each second. 1. The symbol for frequency is f, and the SI unit is the hertz (abbreviated as Hz). 2. It follows that F. Any motion that repeats itself is periodic or harmonic. G. If the motion is a sinusoidal function of time, it is called simple harmonic motion (SHM). -

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples

Linear and Angular Velocity Examples Example 1 Determine the angular displacement in radians of 6.5 revolutions. Round to the nearest tenth. Each revolution equals 2 radians. For 6.5 revolutions, the number of radians is 6.5 2 or 13 . 13 radians equals about 40.8 radians. Example 2 Determine the angular velocity if 4.8 revolutions are completed in 4 seconds. Round to the nearest tenth. The angular displacement is 4.8 2 or 9.6 radians. = t 9.6 = = 9.6 , t = 4 4 7.539822369 Use a calculator. The angular velocity is about 7.5 radians per second. Example 3 AMUSEMENT PARK Jack climbs on a horse that is 12 feet from the center of a merry-go-round. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 rotations per minute. Determine Jack’s angular velocity in radians 4 per second. Round to the nearest hundredth. 1 The merry-go-round makes 3 or 3.25 revolutions per minute. Convert revolutions per minute to radians 4 per second. 3.25 revolutions 1 minute 2 radians 0.3403392041 radian per second 1 minute 60 seconds 1 revolution Jack has an angular velocity of about 0.34 radian per second. Example 4 Determine the linear velocity of a point rotating at an angular velocity of 12 radians per second at a distance of 8 centimeters from the center of the rotating object. Round to the nearest tenth. v = r v = (8)(12 ) r = 8, = 12 v 301.5928947 Use a calculator. The linear velocity is about 301.6 centimeters per second. -

Appendix: Derivations

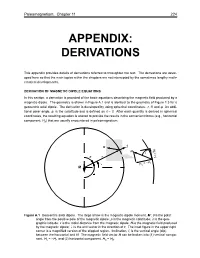

Paleomagnetism: Chapter 11 224 APPENDIX: DERIVATIONS This appendix provides details of derivations referred to throughout the text. The derivations are devel- oped here so that the main topics within the chapters are not interrupted by the sometimes lengthy math- ematical developments. DERIVATION OF MAGNETIC DIPOLE EQUATIONS In this section, a derivation is provided of the basic equations describing the magnetic field produced by a magnetic dipole. The geometry is shown in Figure A.1 and is identical to the geometry of Figure 1.3 for a geocentric axial dipole. The derivation is developed by using spherical coordinates: r, θ, and φ. An addi- tional polar angle, p, is the colatitude and is defined as π – θ. After each quantity is derived in spherical coordinates, the resulting equation is altered to provide the results in the convenient forms (e.g., horizontal component, Hh) that are usually encountered in paleomagnetism. H ^r H H h I = H p r = –Hr H v M Figure A.1 Geocentric axial dipole. The large arrow is the magnetic dipole moment, M ; θ is the polar angle from the positive pole of the magnetic dipole; p is the magnetic colatitude; λ is the geo- graphic latitude; r is the radial distance from the magnetic dipole; H is the magnetic field produced by the magnetic dipole; rˆ is the unit vector in the direction of r. The inset figure in the upper right corner is a magnified version of the stippled region. Inclination, I, is the vertical angle (dip) between the horizontal and H. The magnetic field vector H can be broken into (1) vertical compo- nent, Hv =–Hr, and (2) horizontal component, Hh = Hθ . -

Hub City Powertorque® Shaft Mount Reducers

Hub City PowerTorque® Shaft Mount Reducers PowerTorque® Features and Description .................................................. G-2 PowerTorque Nomenclature ............................................................................................ G-4 Selection Instructions ................................................................................ G-5 Selection By Horsepower .......................................................................... G-7 Mechanical Ratings .................................................................................... G-12 ® Shaft Mount Reducers Dimensions ................................................................................................ G-14 Accessories ................................................................................................ G-15 Screw Conveyor Accessories ..................................................................... G-22 G For Additional Models of Shaft Mount Reducers See Hub City Engineering Manual Sections F & J DOWNLOAD AVAILABLE CAD MODELS AT: WWW.HUBCITYINC.COM Certified prints are available upon request EMAIL: [email protected] • www.hubcityinc.com G-1 Hub City PowerTorque® Shaft Mount Reducers Ten models available from 1/4 HP through 200 HP capacity Manufacturing Quality Manufactured to the highest quality 98.5% standards in the industry, assembled Efficiency using precision manufactured components made from top quality per Gear Stage! materials Designed for the toughest applications in the industry Housings High strength ductile -

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions

Chapter 3 Motion in Two and Three Dimensions 3.1 The Important Stuff 3.1.1 Position In three dimensions, the location of a particle is specified by its location vector, r: r = xi + yj + zk (3.1) If during a time interval ∆t the position vector of the particle changes from r1 to r2, the displacement ∆r for that time interval is ∆r = r1 − r2 (3.2) = (x2 − x1)i +(y2 − y1)j +(z2 − z1)k (3.3) 3.1.2 Velocity If a particle moves through a displacement ∆r in a time interval ∆t then its average velocity for that interval is ∆r ∆x ∆y ∆z v = = i + j + k (3.4) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t As before, a more interesting quantity is the instantaneous velocity v, which is the limit of the average velocity when we shrink the time interval ∆t to zero. It is the time derivative of the position vector r: dr v = (3.5) dt d = (xi + yj + zk) (3.6) dt dx dy dz = i + j + k (3.7) dt dt dt can be written: v = vxi + vyj + vzk (3.8) 51 52 CHAPTER 3. MOTION IN TWO AND THREE DIMENSIONS where dx dy dz v = v = v = (3.9) x dt y dt z dt The instantaneous velocity v of a particle is always tangent to the path of the particle. 3.1.3 Acceleration If a particle’s velocity changes by ∆v in a time period ∆t, the average acceleration a for that period is ∆v ∆v ∆v ∆v a = = x i + y j + z k (3.10) ∆t ∆t ∆t ∆t but a much more interesting quantity is the result of shrinking the period ∆t to zero, which gives us the instantaneous acceleration, a. -

Physics B Topics Overview ∑

Physics 106 Lecture 1 Introduction to Rotation SJ 7th Ed.: Chap. 10.1 to 3 • Course Introduction • Course Rules & Assignment • TiTopics Overv iew • Rotation (rigid body) versus translation (point particle) • Rotation concepts and variables • Rotational kinematic quantities Angular position and displacement Angular velocity & acceleration • Rotation kinematics formulas for constant angular acceleration • Analogy with linear kinematics 1 Physics B Topics Overview PHYSICS A motion of point bodies COVERED: kinematics - translation dynamics ∑Fext = ma conservation laws: energy & momentum motion of “Rigid Bodies” (extended, finite size) PHYSICS B rotation + translation, more complex motions possible COVERS: rigid bodies: fixed size & shape, orientation matters kinematics of rotation dynamics ∑Fext = macm and ∑ Τext = Iα rotational modifications to energy conservation conservation laws: energy & angular momentum TOPICS: 3 weeks: rotation: ▪ angular versions of kinematics & second law ▪ angular momentum ▪ equilibrium 2 weeks: gravitation, oscillations, fluids 1 Angular variables: language for describing rotation Measure angles in radians simple rotation formulas Definition: 360o 180o • 2π radians = full circle 1 radian = = = 57.3o • 1 radian = angle that cuts off arc length s = radius r 2π π s arc length ≡ s = r θ (in radians) θ ≡ rad r r s θ’ θ Example: r = 10 cm, θ = 100 radians Æ s = 1000 cm = 10 m. Rigid body rotation: angular displacement and arc length Angular displacement is the angle an object (rigid body) rotates through during some time interval..... ...also the angle that a reference line fixed in a body sweeps out A rigid body rotates about some rotation axis – a line located somewhere in or near it, pointing in some y direction in space • One polar coordinate θ specifies position of the whole body about this rotation axis. -

Exploring Robotics Joel Kammet Supplemental Notes on Gear Ratios

CORC 3303 – Exploring Robotics Joel Kammet Supplemental notes on gear ratios, torque and speed Vocabulary SI (Système International d'Unités) – the metric system force torque axis moment arm acceleration gear ratio newton – Si unit of force meter – SI unit of distance newton-meter – SI unit of torque Torque Torque is a measure of the tendency of a force to rotate an object about some axis. A torque is meaningful only in relation to a particular axis, so we speak of the torque about the motor shaft, the torque about the axle, and so on. In order to produce torque, the force must act at some distance from the axis or pivot point. For example, a force applied at the end of a wrench handle to turn a nut around a screw located in the jaw at the other end of the wrench produces a torque about the screw. Similarly, a force applied at the circumference of a gear attached to an axle produces a torque about the axle. The perpendicular distance d from the line of force to the axis is called the moment arm. In the following diagram, the circle represents a gear of radius d. The dot in the center represents the axle (A). A force F is applied at the edge of the gear, tangentially. F d A Diagram 1 In this example, the radius of the gear is the moment arm. The force is acting along a tangent to the gear, so it is perpendicular to the radius. The amount of torque at A about the gear axle is defined as = F×d 1 We use the Greek letter Tau ( ) to represent torque. -

6. Non-Inertial Frames

6. Non-Inertial Frames We stated, long ago, that inertial frames provide the setting for Newtonian mechanics. But what if you, one day, find yourself in a frame that is not inertial? For example, suppose that every 24 hours you happen to spin around an axis which is 2500 miles away. What would you feel? Or what if every year you spin around an axis 36 million miles away? Would that have any e↵ect on your everyday life? In this section we will discuss what Newton’s equations of motion look like in non- inertial frames. Just as there are many ways that an animal can be not a dog, so there are many ways in which a reference frame can be non-inertial. Here we will just consider one type: reference frames that rotate. We’ll start with some basic concepts. 6.1 Rotating Frames Let’s start with the inertial frame S drawn in the figure z=z with coordinate axes x, y and z.Ourgoalistounderstand the motion of particles as seen in a non-inertial frame S0, with axes x , y and z , which is rotating with respect to S. 0 0 0 y y We’ll denote the angle between the x-axis of S and the x0- axis of S as ✓.SinceS is rotating, we clearly have ✓ = ✓(t) x 0 0 θ and ✓˙ =0. 6 x Our first task is to find a way to describe the rotation of Figure 31: the axes. For this, we can use the angular velocity vector ! that we introduced in the last section to describe the motion of particles. -

Owner's Manual

OWNER’S MANUAL GET TO KNOW YOUR SYSTEM 1-877-DRY-TIME 3 7 9 8 4 6 3 basementdoctor.com TABLE OF CONTENTS IMPORTANT INFORMATION 1 YOUR SYSTEM 2 WARRANTIES 2 TROUBLESHOOTING 6 ANNUAL MAINTENANCE 8 WHAT TO EXPECT 9 PROFESSIONAL DEHUMIDIFIER 9 ® I-BEAM/FORCE 10 ® POWER BRACES 11 DRY BASEMENT TIPS 12 REFERRAL PROGRAM 15 IMPORTANT INFORMATION Please read the following information: Please allow new concrete to cure (dry) completely before returning your carpet or any other object to the repaired areas. 1 This normally takes 4-6 weeks, depending on conditions and time of year. Curing time may vary. You may experience some minor hairline cracking and dampness 2 with your new concrete. This is normal and does not affect the functionality of your new system. When installing carpet over the new concrete, nailing tack strips 3 is not recommended. This may cause your concrete to crack or shatter. Use Contractor Grade Liquid Nails. It is the responsibility of the Homeowner to keep sump pump discharge lines and downspouts (if applicable) free of roof 4 materials and leaves. If these lines should become clogged with external material, The Basement Doctor® can repair them at an additional charge. If we applied Basement Doctor® Coating to your walls: • This should not be painted over unless the paint contains an anti-microbial for it is the make-up of the coating that prohibits 5 mold growth. • This product may not cover all previous colors on your wall. • It is OK to panel or drywall over the Basement Doctor® Coating.