A Note on Oviposition by Lymnaea Stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Lymnaeidae) on Shells of Conspecifics Under Laboratory Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic

water Review Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic Valentina S. Artamonova 1, Ivan N. Bolotov 2,3,4, Maxim V. Vinarski 4 and Alexander A. Makhrov 1,4,* 1 A. N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Molecular Ecology and Phylogenetics, Northern Arctic Federal University, 163002 Arkhangelsk, Russia; [email protected] 3 Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, 163000 Arkhangelsk, Russia 4 Laboratory of Macroecology & Biogeography of Invertebrates, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of zoogeographic, paleogeographic, and molecular data has shown that the ancestors of many fresh- and brackish-water cold-tolerant hydrobionts of the Mediterranean region and the Danube River basin likely originated in East Asia or Central Asia. The fish genera Gasterosteus, Hucho, Oxynoemacheilus, Salmo, and Schizothorax are examples of these groups among vertebrates, and the genera Magnibursatus (Trematoda), Margaritifera, Potomida, Microcondylaea, Leguminaia, Unio (Mollusca), and Phagocata (Planaria), among invertebrates. There is reason to believe that their ancestors spread to Europe through the Paratethys (or the proto-Paratethys basin that preceded it), where intense speciation took place and new genera of aquatic organisms arose. Some of the forms that originated in the Paratethys colonized the Mediterranean, and overwhelming data indicate that Citation: Artamonova, V.S.; Bolotov, representatives of the genera Salmo, Caspiomyzon, and Ecrobia migrated during the Miocene from I.N.; Vinarski, M.V.; Makhrov, A.A. -

Taxonomic Status of Stagnicola Palustris (O

Folia Malacol. 23(1): 3–18 http://dx.doi.org/10.12657/folmal.023.003 TAXONOMIC STATUS OF STAGNICOLA PALUSTRIS (O. F. MÜLLER, 1774) AND S. TURRICULA (HELD, 1836) (GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: LYMNAEIDAE) IN VIEW OF NEW MOLECULAR AND CHOROLOGICAL DATA Joanna Romana Pieńkowska1, eliza Rybska2, Justyna banasiak1, maRia wesołowska1, andRzeJ lesicki1 1Department of Cell Biology, Institute of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Poznań, Poland (e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]) 2Nature Education and Conservation, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Poznań, Poland ([email protected], [email protected]) abstRact: Analyses of nucleotide sequences of 5’- and 3’- ends of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (5’COI, 3’COI) and fragments of internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) of nuclear rDNA gene confirmed the status of Stagnicola corvus (Gmelin), Lymnaea stagnalis L. and Ladislavella terebra (Westerlund) as separate species. The same results showed that Stagnicola palustris (O. F. Müll.) and S. turricula (Held) could also be treated as separate species, but compared to the aforementioned lymnaeids, the differences in the analysed sequences between them were much smaller, although clearly recognisable. In each case they were also larger than the differences between these molecular features of specimens from different localities of S. palustris or S. turricula. New data on the distribution of S. palustris and S. turricula in Poland showed – in contrast to the earlier reports – that their ranges overlapped. This sympatric distribution together with the small but clearly marked differences in molecular features as well as with differences in the male genitalia between S. -

Molecular Characterization of Liver Fluke Intermediate Host Lymnaeids

Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 17 (2019) 100318 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vprsr Original Article Molecular characterization of liver fluke intermediate host lymnaeids (Gastropoda: Pulmonata) snails from selected regions of Okavango Delta of T Botswana, KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga provinces of South Africa ⁎ Mokgadi P. Malatji , Jennifer Lamb, Samson Mukaratirwa School of Life Sciences, College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Durban 4001, South Africa ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Lymnaeidae snail species are known to be intermediate hosts of human and livestock helminths parasites, Lymnaeidae especially Fasciola species. Identification of these species and their geographical distribution is important to ITS-2 better understand the epidemiology of the disease. Significant diversity has been observed in the shell mor- Okavango delta (OKD) phology of snails from the Lymnaeidae family and the systematics within this family is still unclear, especially KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) province when the anatomical traits among various species have been found to be homogeneous. Although there are Mpumalanga province records of lymnaeid species of southern Africa based on shell morphology and controversial anatomical traits, there is paucity of information on the molecular identification and phylogenetic relationships of the different taxa. Therefore, this study aimed at identifying populations of Lymnaeidae snails from selected sites of the Okavango Delta (OKD) in Botswana, and sites located in the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) and Mpumalanga (MP) provinces of South Africa using molecular techniques. Lymnaeidae snails were collected from 8 locations from the Okavango delta in Botswana, 9 from KZN and one from MP provinces and were identified based on phy- logenetic analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS-2). -

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry. -

Anisus Vorticulus (Troschel 1834) (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) in Northeast Germany

JOURNAL OF CONCHOLOGY (2013), VOL.41, NO.3 389 SOME ECOLOGICAL PECULIARITIES OF ANISUS VORTICULUS (TROSCHEL 1834) (GASTROPODA: PLANORBIDAE) IN NORTHEAST GERMANY MICHAEL L. ZETTLER Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde, Seestr. 15, D-18119 Rostock, Germany Abstract During the EU Habitats Directive monitoring between 2008 and 2010 the ecological requirements of the gastropod species Anisus vorticulus (Troschel 1834) were investigated in 24 different waterbodies of northeast Germany. 117 sampling units were analyzed quantitatively. 45 of these units contained living individuals of the target species in abundances between 4 and 616 individuals m-2. More than 25.300 living individuals of accompanying freshwater mollusc species and about 9.400 empty shells were counted and determined to the species level. Altogether 47 species were identified. The benefit of enhanced knowledge on the ecological requirements was gained due to the wide range and high number of sampled habitats with both obviously convenient and inconvenient living conditions for A. vorticulus. In northeast Germany the amphibian zones of sheltered mesotrophic lake shores, swampy (lime) fens and peat holes which are sun exposed and have populations of any Chara species belong to the optimal, continuously and densely colonized biotopes. The cluster analysis emphasized that A. vorticulus was associated with a typical species composition, which can be named as “Anisus-vorticulus-community”. In compliance with that both the frequency of combined occurrence of species and their similarity in relative abundance are important. The following species belong to the “Anisus-vorticulus-community” in northeast Germany: Pisidium obtusale, Pisidium milium, Pisidium pseudosphaerium, Bithynia leachii, Stagnicola palustris, Valvata cristata, Bathyomphalus contortus, Bithynia tentaculata, Anisus vortex, Hippeutis complanatus, Gyraulus crista, Physa fontinalis, Segmentina nitida and Anisus vorticulus. -

DNA Multigene Sequencing of Topotypic Specimens of the Fascioliasis Vector Lymnaea Diaphana and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Genus Pectinidens (Gastropoda)

Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 107(1): 111-124, February 2012 111 DNA multigene sequencing of topotypic specimens of the fascioliasis vector Lymnaea diaphana and phylogenetic analysis of the genus Pectinidens (Gastropoda) Maria Dolores Bargues1/+, Roberto Luis Mera y Sierra2, Patricio Artigas1, Santiago Mas-Coma1 1Departamento de Parasitología, Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad de Valencia, Av. Vicente Andrés Estellés s/n, 46100 Burjassot, Valencia, Spain 2Cátedra de Parasitología y Enfermedades Parasitarias, Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Juan Agustín Maza, Guaymallén, Mendoza, Argentina Freshwater lymnaeid snails are crucial in defining transmission and epidemiology of fascioliasis. In South Amer- ica, human endemic areas are related to high altitudes in Andean regions. The species Lymnaea diaphana has, how- ever, been involved in low altitude areas of Chile, Argentina and Peru where human infection also occurs. Complete nuclear ribosomal DNA 18S, internal transcribed spacer (ITS)-2 and ITS-1 and fragments of mitochondrial DNA 16S and cytochrome c oxidase (cox)1 genes of L. diaphana specimens from its type locality offered 1,848, 495, 520, 424 and 672 bp long sequences. Comparisons with New and Old World Galba/Fossaria, Palaearctic stagnicolines, Nearctic stagnicolines, Old World Radix and Pseudosuccinea allowed to conclude that (i) L. diaphana shows se- quences very different from all other lymnaeids, (ii) each marker allows its differentiation, except cox1 amino acid sequence, and (iii) L. diaphana is not a fossarine lymnaeid, but rather an archaic relict form derived from the oldest North American stagnicoline ancestors. Phylogeny and large genetic distances support the genus Pectinidens as the first stagnicoline representative in the southern hemisphere, including colonization of extreme world regions, as most southern Patagonia, long time ago. -

REVEALING BIOTIC DIVERSITY: HOW DO COMPLEX ENVIRONMENTS INFLUENCE HUMAN SCHISTOSOMIASIS in a HYPERENDEMIC AREA Martina R

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Biology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-9-2018 REVEALING BIOTIC DIVERSITY: HOW DO COMPLEX ENVIRONMENTS INFLUENCE HUMAN SCHISTOSOMIASIS IN A HYPERENDEMIC AREA Martina R. Laidemitt Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds Recommended Citation Laidemitt, Martina R.. "REVEALING BIOTIC DIVERSITY: HOW DO COMPLEX ENVIRONMENTS INFLUENCE HUMAN SCHISTOSOMIASIS IN A HYPERENDEMIC AREA." (2018). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/279 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Martina Rose Laidemitt Candidate Department of Biology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Eric S. Loker, Chairperson Dr. Jennifer A. Rudgers Dr. Stephen A. Stricker Dr. Michelle L. Steinauer Dr. William E. Secor i REVEALING BIOTIC DIVERSITY: HOW DO COMPLEX ENVIRONMENTS INFLUENCE HUMAN SCHISTOSOMIASIS IN A HYPERENDEMIC AREA By Martina R. Laidemitt B.S. Biology, University of Wisconsin- La Crosse, 2011 DISSERT ATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Biology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July 2018 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my major advisor, Dr. Eric Samuel Loker who has provided me unlimited support over the past six years. His knowledge and pursuit of parasitology is something I will always admire. I would like to thank my coauthors for all their support and hard work, particularly Dr. -

Download Preprint

1 Mobilising molluscan models and genomes in biology 2 Angus Davison1 and Maurine Neiman2 3 1. School of Life Sciences, University Park, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK 4 2. Department of Biology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA and Department of Gender, 5 Women's, and Sexuality Studies, University of Iowa, Iowa, City, IA, USA 6 Abstract 7 Molluscs are amongst the most ancient, diverse, and important of all animal taxa. Even so, 8 no individual mollusc species has emerged as a broadly applied model system in biology. 9 We here make the case that both perceptual and methodological barriers have played a role 10 in the relative neglect of molluscs as research organisms. We then summarize the current 11 application and potential of molluscs and their genomes to address important questions in 12 animal biology, and the state of the field when it comes to the availability of resources such 13 as genome assemblies, cell lines, and other key elements necessary to mobilising the 14 development of molluscan model systems. We conclude by contending that a cohesive 15 research community that works together to elevate multiple molluscan systems to ‘model’ 16 status will create new opportunities in addressing basic and applied biological problems, 17 including general features of animal evolution. 18 Introduction 19 Molluscs are globally important as sources of food, calcium and pearls, and as vectors of 20 human disease. From an evolutionary perspective, molluscs are notable for their remarkable 21 diversity: originating over 500 million years ago, there are over 70,000 extant mollusc 22 species [1], with molluscs present in virtually every ecosystem. -

Gastropoda, Mollusca)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/087254; this version posted November 11, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. An annotated draft genome for Radix auricularia (Gastropoda, Mollusca) Tilman Schell 1,2 *, Barbara Feldmeyer 2, Hanno Schmidt 2, Bastian Greshake 3, Oliver Tills 4, Manuela Truebano 4, Simon D. Rundle 4, Juraj Paule 5, Ingo Ebersberger 3,2, Markus Pfenninger 1,2 1 Molecular Ecology Group, Institute for Ecology, Evolution and Diversity, Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 2 Adaptation and Climate, Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 3 Department for Applied Bioinformatics, Institute for Cell Biology and Neuroscience, Goethe- University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 4 Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre, Marine Institute, School of Marine Science and Engineering, Plymouth University, Plymouth, United Kingdom 5 Department of Botany and Molecular Evolution, Senckenberg Research Institute, Frankfurt am Main, Germany * Author for Correspondence: Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Tel.: +49 (0)69 75 42 18 30, E-mail: [email protected] Data deposition: BioProject: PRJNA350764, SRA: SRP092167 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/087254; this version posted November 11, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Freshwater Snail Guide

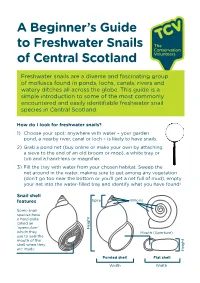

A Beginner’s Guide to Freshwater Snails of Central Scotland Freshwater snails are a diverse and fascinating group of molluscs found in ponds, lochs, canals, rivers and watery ditches all across the globe. This guide is a simple introduction to some of the most commonly encountered and easily identifiable freshwater snail species in Central Scotland. How do I look for freshwater snails? 1) Choose your spot: anywhere with water – your garden pond, a nearby river, canal or loch – is likely to have snails. 2) Grab a pond net (buy online or make your own by attaching a sieve to the end of an old broom or mop), a white tray or tub and a hand-lens or magnifier. 3) Fill the tray with water from your chosen habitat. Sweep the net around in the water, making sure to get among any vegetation (don’t go too near the bottom or you’ll get a net full of mud), empty your net into the water-filled tray and identify what you have found! Snail shell features Spire Whorls Some snail species have a hard plate called an ‘operculum’ Height which they Mouth (Aperture) use to seal the mouth of the shell when they are inside Height Pointed shell Flat shell Width Width Pond Snails (Lymnaeidae) Variable in size. Mouth always on right-hand side, shells usually long and pointed. Great Pond Snail Common Pond Snail Lymnaea stagnalis Radix balthica Largest pond snail. Common in ponds Fairly rounded and ’fat’. Common in weedy lakes, canals and sometimes slow river still waters. pools. -

The Freshwater Snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of Mexico: Updated Checklist, Endemicity Hotspots, Threats and Conservation Status

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 91 (2020): e912909 Taxonomy and systematics The freshwater snails (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of Mexico: updated checklist, endemicity hotspots, threats and conservation status Los caracoles dulceacuícolas (Mollusca: Gastropoda) de México: listado actualizado, hotspots de endemicidad, amenazas y estado de conservación Alexander Czaja a, *, Iris Gabriela Meza-Sánchez a, José Luis Estrada-Rodríguez a, Ulises Romero-Méndez a, Jorge Sáenz-Mata a, Verónica Ávila-Rodríguez a, Jorge Luis Becerra-López a, Josué Raymundo Estrada-Arellano a, Gabriel Fernando Cardoza-Martínez a, David Ramiro Aguillón-Gutiérrez a, Diana Gabriela Cordero-Torres a, Alan P. Covich b a Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Av.Universidad s/n, Fraccionamiento Filadelfia, 35010 Gómez Palacio, Durango, Mexico b Institute of Ecology, Odum School of Ecology, University of Georgia, 140 East Green Street, Athens, GA 30602-2202, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] (A. Czaja) Received: 14 April 2019; accepted: 6 November 2019 Abstract We present an updated checklist of native Mexican freshwater gastropods with data on their general distribution, hotspots of endemicity, threats, and for the first time, their estimated conservation status. The list contains 193 species, representing 13 families and 61 genera. Of these, 103 species (53.4%) and 12 genera are endemic to Mexico, and 75 species are considered local endemics because of their restricted distribution to very small areas. Using NatureServe Ranking, 9 species (4.7%) are considered possibly or presumably extinct, 40 (20.7%) are critically imperiled, 30 (15.5%) are imperiled, 15 (7.8%) are vulnerable and only 64 (33.2%) are currently stable. -

Aquatic Snails of the Snake and Green River Basins of Wyoming

Aquatic snails of the Snake and Green River Basins of Wyoming Lusha Tronstad Invertebrate Zoologist Wyoming Natural Diversity Database University of Wyoming 307-766-3115 [email protected] Mark Andersen Information Systems and Services Coordinator Wyoming Natural Diversity Database University of Wyoming 307-766-3036 [email protected] Suggested citation: Tronstad, L.M. and M. D. Andersen. 2018. Aquatic snails of the Snake and Green River Basins of Wyoming. Report prepared by the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database for the Wyoming Fish and Wildlife Department. 1 Abstract Freshwater snails are a diverse group of mollusks that live in a variety of aquatic ecosystems. Many snail species are of conservation concern around the globe. About 37-39 species of aquatic snails likely live in Wyoming. The current study surveyed the Snake and Green River basins in Wyoming and identified 22 species and possibly discovered a new operculate snail. We surveyed streams, wetlands, lakes and springs throughout the basins at randomly selected locations. We measured habitat characteristics and basic water quality at each site. Snails were usually most abundant in ecosystems with higher standing stocks of algae, on solid substrate (e.g., wood or aquatic vegetation) and in habitats with slower water velocity (e.g., backwater and margins of streams). We created an aquatic snail key for identifying species in Wyoming. The key is a work in progress that will be continually updated to reflect changes in taxonomy and new knowledge. We hope the snail key will be used throughout the state to unify snail identification and create better data on Wyoming snails.