The Real Threat of Swimmers' Itch in Anthropogenic Recreational Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic

water Review Fresh- and Brackish-Water Cold-Tolerant Species of Southern Europe: Migrants from the Paratethys That Colonized the Arctic Valentina S. Artamonova 1, Ivan N. Bolotov 2,3,4, Maxim V. Vinarski 4 and Alexander A. Makhrov 1,4,* 1 A. N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119071 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Molecular Ecology and Phylogenetics, Northern Arctic Federal University, 163002 Arkhangelsk, Russia; [email protected] 3 Federal Center for Integrated Arctic Research, Russian Academy of Sciences, 163000 Arkhangelsk, Russia 4 Laboratory of Macroecology & Biogeography of Invertebrates, Saint Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of zoogeographic, paleogeographic, and molecular data has shown that the ancestors of many fresh- and brackish-water cold-tolerant hydrobionts of the Mediterranean region and the Danube River basin likely originated in East Asia or Central Asia. The fish genera Gasterosteus, Hucho, Oxynoemacheilus, Salmo, and Schizothorax are examples of these groups among vertebrates, and the genera Magnibursatus (Trematoda), Margaritifera, Potomida, Microcondylaea, Leguminaia, Unio (Mollusca), and Phagocata (Planaria), among invertebrates. There is reason to believe that their ancestors spread to Europe through the Paratethys (or the proto-Paratethys basin that preceded it), where intense speciation took place and new genera of aquatic organisms arose. Some of the forms that originated in the Paratethys colonized the Mediterranean, and overwhelming data indicate that Citation: Artamonova, V.S.; Bolotov, representatives of the genera Salmo, Caspiomyzon, and Ecrobia migrated during the Miocene from I.N.; Vinarski, M.V.; Makhrov, A.A. -

Diversity of Echinostomes (Digenea: Echinostomatidae) in Their Snail Hosts at High Latitudes

Parasite 28, 59 (2021) Ó C. Pantoja et al., published by EDP Sciences, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2021054 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9816A6C3-D479-4E1D-9880-2A7E1DBD2097 Available online at: www.parasite-journal.org RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Diversity of echinostomes (Digenea: Echinostomatidae) in their snail hosts at high latitudes Camila Pantoja1,2, Anna Faltýnková1,* , Katie O’Dwyer3, Damien Jouet4, Karl Skírnisson5, and Olena Kudlai1,2 1 Institute of Parasitology, Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Branišovská 31, 370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic 2 Institute of Ecology, Nature Research Centre, Akademijos 2, 08412 Vilnius, Lithuania 3 Marine and Freshwater Research Centre, Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, H91 T8NW, Galway, Ireland 4 BioSpecT EA7506, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne, 51 rue Cognacq-Jay, 51096 Reims Cedex, France 5 Laboratory of Parasitology, Institute for Experimental Pathology, Keldur, University of Iceland, IS-112 Reykjavík, Iceland Received 26 April 2021, Accepted 24 June 2021, Published online 28 July 2021 Abstract – The biodiversity of freshwater ecosystems globally still leaves much to be discovered, not least in the trematode parasite fauna they support. Echinostome trematode parasites have complex, multiple-host life-cycles, often involving migratory bird definitive hosts, thus leading to widespread distributions. Here, we examined the echinostome diversity in freshwater ecosystems at high latitude locations in Iceland, Finland, Ireland and Alaska (USA). We report 14 echinostome species identified morphologically and molecularly from analyses of nad1 and 28S rDNA sequence data. We found echinostomes parasitising snails of 11 species from the families Lymnaeidae, Planorbidae, Physidae and Valvatidae. -

A Note on Oviposition by Lymnaea Stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Lymnaeidae) on Shells of Conspecifics Under Laboratory Conditions

Folia Malacol. 25(2): 101–108 https://doi.org/10.12657/folmal.025.007 A NOTE ON OVIPOSITION BY LYMNAEA STAGNALIS (LINNAEUS, 1758) (GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: LYMNAEIDAE) ON SHELLS OF CONSPECIFICS UNDER LABORATORY CONDITIONS PAOLA LOMBARDO1*, FRANCESCO PAOLO MICCOLI2 1 Limno Consulting, via Bedollo 303, I-00124 Rome, Italy (e-mail: [email protected]) 2 University of L’Aquila, Coppito Science Center, I-67100 L’Aquila, Italy (e-mail: [email protected]) *corresponding author ABSTRACT: Oviposition by Lymnaea stagnalis (L.) on shells of conspecifics has been reported anecdotally from laboratory observations. In order to gain the first quantitative insight into this behaviour, we have quantified the proportion of individuals bearing egg clutches in a long-term monospecific outdoor laboratory culture of L. stagnalis during two consecutive late-summer months. The snails were assigned to size classes based on shell height. Differences between the size class composition of clutch-bearers and of the general population were statistically compared by means of Pearson’s distance χ²P analysis. Egg clutches were laid on snails of shell height >15 mm (i.e. reproductive-age individuals), with significant selection for the larger size classes (shell height 25–40 mm). While the mechanisms of and reasons behind such behaviour remain unknown, selection of larger adults as egg-carriers may have ecological implications at the population level. KEY WORDS: freshwater gastropods, Lymnaea stagnalis, great pond snail, reproductive behaviour INTRODUCTION Lymnaea stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758) is a common & CARRIKER 1946, TER MAAT et al. 1989, ELGER & Holarctic freshwater gastropod, inhabiting most of LEMOINE 2005, GROSS & LOMBARDO in press). -

Taxonomic Status of Stagnicola Palustris (O

Folia Malacol. 23(1): 3–18 http://dx.doi.org/10.12657/folmal.023.003 TAXONOMIC STATUS OF STAGNICOLA PALUSTRIS (O. F. MÜLLER, 1774) AND S. TURRICULA (HELD, 1836) (GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: LYMNAEIDAE) IN VIEW OF NEW MOLECULAR AND CHOROLOGICAL DATA Joanna Romana Pieńkowska1, eliza Rybska2, Justyna banasiak1, maRia wesołowska1, andRzeJ lesicki1 1Department of Cell Biology, Institute of Experimental Biology, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Poznań, Poland (e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]) 2Nature Education and Conservation, Faculty of Biology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Poznań, Poland ([email protected], [email protected]) abstRact: Analyses of nucleotide sequences of 5’- and 3’- ends of mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (5’COI, 3’COI) and fragments of internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) of nuclear rDNA gene confirmed the status of Stagnicola corvus (Gmelin), Lymnaea stagnalis L. and Ladislavella terebra (Westerlund) as separate species. The same results showed that Stagnicola palustris (O. F. Müll.) and S. turricula (Held) could also be treated as separate species, but compared to the aforementioned lymnaeids, the differences in the analysed sequences between them were much smaller, although clearly recognisable. In each case they were also larger than the differences between these molecular features of specimens from different localities of S. palustris or S. turricula. New data on the distribution of S. palustris and S. turricula in Poland showed – in contrast to the earlier reports – that their ranges overlapped. This sympatric distribution together with the small but clearly marked differences in molecular features as well as with differences in the male genitalia between S. -

Reinvestigation of the Sperm Ultrastructure of Hypoderaeum

Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript Hypoderaeum conoideum Ms ParasitolRes REV.docx Click here to view linked References 1 Reinvestigation of the sperm ultrastructure of Hypoderaeum conoideum (Digenea: 1 2 2 Echinostomatidae) 3 4 5 3 6 7 4 Jordi Miquel1,2,*, Magalie René Martellet3, Lucrecia Acosta4, Rafael Toledo5, Anne- 8 9 6 10 5 Françoise Pétavy 11 12 6 13 14 7 1 Secció de Parasitologia, Departament de Biologia, Sanitat i Medi ambient, Facultat de 15 16 17 8 Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Universitat de Barcelona, Av. Joan XXIII, sn, 08028 18 19 9 Barcelona, Spain 20 21 2 22 10 Institut de Recerca de la Biodiversitat (IRBio), Universitat de Barcelona, Av. Diagonal, 645, 23 24 11 08028 Barcelona, Spain 25 26 3 27 12 Université Clermont Auvergne, INRA, VetAgro Sup, UMR EPIA Epidémiologie des 28 29 13 maladies animales et zoonotiques, 63122 Saint-Genès-Champanelle, France 30 31 14 4 Área de Parasitología del Departamento de Agroquímica y Medioambiente, Universidad 32 33 34 15 Miguel Hernández de Elche, Alicante, Spain 35 36 16 5 Departament de Farmàcia i Tecnologia Farmacèutica i Parasitologia, Facultat de Farmàcia, 37 38 39 17 Universitat de València, 46100 Burjassot, València, Spain 40 41 18 6 Laboratoire de Parasitologie et Mycologie Médicale, Faculté de Pharmacie, Université Claude 42 43 44 19 Bernard-Lyon 1, 8 Av. Rockefeller, 69373 Lyon Cedex 08, France 45 46 20 47 48 49 21 *Corresponding author: 50 51 22 Jordi Miquel 52 53 23 Secció de Parasitologia, Departament de Biologia, Sanitat i Medi Ambient, Facultat de 54 55 56 24 Farmàcia i Ciències de l’Alimentació, Universitat de Barcelona, Av. -

Ecological Divergence and Reproductive Isolation Between the Freshwater Snails Lymnaea Peregra (Müller 1774) and L

Research Collection Doctoral Thesis Ecological divergence and reproductive isolation between the freshwater snails Lymnaea peregra (Müller 1774) and L. ovata (Draparnaud 1805) Author(s): Wullschleger, Esther Publication Date: 2000 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-004099299 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library DissETHNo. 13898 Ecological divergence and reproductive isolation between the freshwa¬ ter snails Lymnaea peregra (Müller 1774) and L. ovata (Draparnaud 1805) A dissertation submitted to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zürich for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences Presented by Esther Wullschleger ,^r;-' Dipl. Biol. Univ. Zürich born October 22nd, 1966 ?<°" in Zürich, Switzerland **fc-LA Submitted for the approval of Prof. Dr. Paul Schmid-Hempel, examiner Dr. Jukka Jokela, co-examiner Prof. Dr. Paul Ward, co-examiner 2000 2 "J'ai également recueilli toute une série de formes de L ovata dont les extrêmes, très rares cependant, sont bien voisins de l'espèce de Müller Mais je dois dire que, si dans une colonie de L ovata, on constate parfois de ces individus extrêmes qui ne sont guère discernables de L peregra, je n'ai jamais observé une seule colonie de cette dernière espèce qui présente le fait inverse, c'est-à-dire des individus qui pourraient être confondus avec l'espèce de Draparnaud II semble donc bien qu'il y ait deux types spécifiques, l'un polymorphe, L ovata, don't certains exemplaires simulent par convergence le second, L peregra, celui-ci ne montrant pas ou bien " peu de variabilité dans la direction du premier J Favre (1927) 3 Contents Contents 3 Summary 4 Zusammenfassung 5 General introduction and thesis outline 7 Lymnaea (Radix) peregra/ovata as a study system 10 Thesis outline 12 1. -

Anisus Vorticulus (Troschel 1834) (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) in Northeast Germany

JOURNAL OF CONCHOLOGY (2013), VOL.41, NO.3 389 SOME ECOLOGICAL PECULIARITIES OF ANISUS VORTICULUS (TROSCHEL 1834) (GASTROPODA: PLANORBIDAE) IN NORTHEAST GERMANY MICHAEL L. ZETTLER Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde, Seestr. 15, D-18119 Rostock, Germany Abstract During the EU Habitats Directive monitoring between 2008 and 2010 the ecological requirements of the gastropod species Anisus vorticulus (Troschel 1834) were investigated in 24 different waterbodies of northeast Germany. 117 sampling units were analyzed quantitatively. 45 of these units contained living individuals of the target species in abundances between 4 and 616 individuals m-2. More than 25.300 living individuals of accompanying freshwater mollusc species and about 9.400 empty shells were counted and determined to the species level. Altogether 47 species were identified. The benefit of enhanced knowledge on the ecological requirements was gained due to the wide range and high number of sampled habitats with both obviously convenient and inconvenient living conditions for A. vorticulus. In northeast Germany the amphibian zones of sheltered mesotrophic lake shores, swampy (lime) fens and peat holes which are sun exposed and have populations of any Chara species belong to the optimal, continuously and densely colonized biotopes. The cluster analysis emphasized that A. vorticulus was associated with a typical species composition, which can be named as “Anisus-vorticulus-community”. In compliance with that both the frequency of combined occurrence of species and their similarity in relative abundance are important. The following species belong to the “Anisus-vorticulus-community” in northeast Germany: Pisidium obtusale, Pisidium milium, Pisidium pseudosphaerium, Bithynia leachii, Stagnicola palustris, Valvata cristata, Bathyomphalus contortus, Bithynia tentaculata, Anisus vortex, Hippeutis complanatus, Gyraulus crista, Physa fontinalis, Segmentina nitida and Anisus vorticulus. -

DNA Multigene Sequencing of Topotypic Specimens of the Fascioliasis Vector Lymnaea Diaphana and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Genus Pectinidens (Gastropoda)

Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 107(1): 111-124, February 2012 111 DNA multigene sequencing of topotypic specimens of the fascioliasis vector Lymnaea diaphana and phylogenetic analysis of the genus Pectinidens (Gastropoda) Maria Dolores Bargues1/+, Roberto Luis Mera y Sierra2, Patricio Artigas1, Santiago Mas-Coma1 1Departamento de Parasitología, Facultad de Farmacia, Universidad de Valencia, Av. Vicente Andrés Estellés s/n, 46100 Burjassot, Valencia, Spain 2Cátedra de Parasitología y Enfermedades Parasitarias, Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Juan Agustín Maza, Guaymallén, Mendoza, Argentina Freshwater lymnaeid snails are crucial in defining transmission and epidemiology of fascioliasis. In South Amer- ica, human endemic areas are related to high altitudes in Andean regions. The species Lymnaea diaphana has, how- ever, been involved in low altitude areas of Chile, Argentina and Peru where human infection also occurs. Complete nuclear ribosomal DNA 18S, internal transcribed spacer (ITS)-2 and ITS-1 and fragments of mitochondrial DNA 16S and cytochrome c oxidase (cox)1 genes of L. diaphana specimens from its type locality offered 1,848, 495, 520, 424 and 672 bp long sequences. Comparisons with New and Old World Galba/Fossaria, Palaearctic stagnicolines, Nearctic stagnicolines, Old World Radix and Pseudosuccinea allowed to conclude that (i) L. diaphana shows se- quences very different from all other lymnaeids, (ii) each marker allows its differentiation, except cox1 amino acid sequence, and (iii) L. diaphana is not a fossarine lymnaeid, but rather an archaic relict form derived from the oldest North American stagnicoline ancestors. Phylogeny and large genetic distances support the genus Pectinidens as the first stagnicoline representative in the southern hemisphere, including colonization of extreme world regions, as most southern Patagonia, long time ago. -

Genetic Variation and Phylogenetic Relationship of Hypoderaeum

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 2020; 13(11): 515-520 515 Original Article Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine journal homepage: www.apjtm.org Impact Factor: 1.77 doi: 10.4103/1995-7645.295362 Genetic variation and phylogenetic relationship of Hypoderaeum conoideum (Bloch, 1782) Dietz, 1909 (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae) inferred from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequences Chairat Tantrawatpan1, Weerachai Saijuntha2 1Division of Cell Biology, Department of Preclinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Rangsit Campus, Pathumthani 12120, Thailand 2Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham 44150, Thailand ABSTRACT 1. Introduction Objective: To explore genetic variations of Hypoderaeum conoideum Hypoderaeum (H.) conoideum (Bloch, 1782) Dietz, 1909 is a species collected from domestic ducks from 12 different localities in of digenetic trematode in the family Echinostomatidae, which Thailand and Lao PDR, as well as their phylogenetic relationship is the causative agent of human and animal echinostomiasis . [1,2] with American and European isolates. The life cycle of H. conoideum has been extensively studied Methods: The nucleotide sequences of their nuclear ribosomal experimentally . A wide variety of freshwater snails, especially [3,4] DNA (ITS), mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (CO1), the lymnaeid species, are the first intermediate hosts and shed and NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 (ND1) were used to analyze cercariae . Aquatic animals, such as bivalves, fishes, and tadpoles, [5] genetic diversity indices. often act as second intermediate hosts. Eating these raw or partially- Results: We found relatively high levels of nucleotide cooked aquatic animals has been identified as the primary mode of polymorphism in ND1 (4.02%), whereas moderate and low levels transmission . -

Gastropoda, Mollusca)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/087254; this version posted November 11, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. An annotated draft genome for Radix auricularia (Gastropoda, Mollusca) Tilman Schell 1,2 *, Barbara Feldmeyer 2, Hanno Schmidt 2, Bastian Greshake 3, Oliver Tills 4, Manuela Truebano 4, Simon D. Rundle 4, Juraj Paule 5, Ingo Ebersberger 3,2, Markus Pfenninger 1,2 1 Molecular Ecology Group, Institute for Ecology, Evolution and Diversity, Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 2 Adaptation and Climate, Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 3 Department for Applied Bioinformatics, Institute for Cell Biology and Neuroscience, Goethe- University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany 4 Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre, Marine Institute, School of Marine Science and Engineering, Plymouth University, Plymouth, United Kingdom 5 Department of Botany and Molecular Evolution, Senckenberg Research Institute, Frankfurt am Main, Germany * Author for Correspondence: Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Tel.: +49 (0)69 75 42 18 30, E-mail: [email protected] Data deposition: BioProject: PRJNA350764, SRA: SRP092167 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/087254; this version posted November 11, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

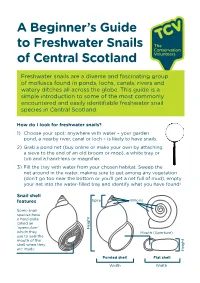

Freshwater Snail Guide

A Beginner’s Guide to Freshwater Snails of Central Scotland Freshwater snails are a diverse and fascinating group of molluscs found in ponds, lochs, canals, rivers and watery ditches all across the globe. This guide is a simple introduction to some of the most commonly encountered and easily identifiable freshwater snail species in Central Scotland. How do I look for freshwater snails? 1) Choose your spot: anywhere with water – your garden pond, a nearby river, canal or loch – is likely to have snails. 2) Grab a pond net (buy online or make your own by attaching a sieve to the end of an old broom or mop), a white tray or tub and a hand-lens or magnifier. 3) Fill the tray with water from your chosen habitat. Sweep the net around in the water, making sure to get among any vegetation (don’t go too near the bottom or you’ll get a net full of mud), empty your net into the water-filled tray and identify what you have found! Snail shell features Spire Whorls Some snail species have a hard plate called an ‘operculum’ Height which they Mouth (Aperture) use to seal the mouth of the shell when they are inside Height Pointed shell Flat shell Width Width Pond Snails (Lymnaeidae) Variable in size. Mouth always on right-hand side, shells usually long and pointed. Great Pond Snail Common Pond Snail Lymnaea stagnalis Radix balthica Largest pond snail. Common in ponds Fairly rounded and ’fat’. Common in weedy lakes, canals and sometimes slow river still waters. pools. -

Impacts of Neonicotinoids on Molluscs: What We Know and What We Need to Know

toxics Review Impacts of Neonicotinoids on Molluscs: What We Know and What We Need to Know Endurance E Ewere 1,2 , Amanda Reichelt-Brushett 1 and Kirsten Benkendorff 1,3,* 1 Marine Ecology Research Centre, School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, P.O. Box 157, Lismore, NSW 2480, Australia; [email protected] (E.E.E.); [email protected] (A.R.-B.) 2 Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Benin, PMB 1154 Benin City, Nigeria 3 National Marine Science Centre, School of Environment, Science and Engineering, Southern Cross University, 2 Bay Drive, Coffs Harbour, NSW 2450, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The broad utilisation of neonicotinoids in agriculture has led to the unplanned contam- ination of adjacent terrestrial and aquatic systems around the world. Environmental monitoring regularly detects neonicotinoids at concentrations that may cause negative impacts on molluscs. The toxicity of neonicotinoids to some non-target invertebrates has been established; however, informa- tion on mollusc species is limited. Molluscs are likely to be exposed to various concentrations of neonicotinoids in the soil, food and water, which could increase their vulnerability to other sources of mortality and cause accidental exposure of other organisms higher in the food chain. This review examines the impacts of various concentrations of neonicotinoids on molluscs, including behavioural, physiological and biochemical responses. The review also identifies knowledge gaps and provides recommendations for future studies, to ensure a more comprehensive understanding of impacts from neonicotinoid exposure to molluscs. Keywords: non-target species; toxicity; biomarker; pesticide; bivalve; gastropod; cephalopod; Citation: Ewere, E.E; environmental concentration Reichelt-Brushett, A.; Benkendorff, K.