Aquatic Snails of the Snake and Green River Basins of Wyoming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beiträge Zur Kenntnis Der Paläarktischen Planorbidae. Wilhelm A. Lindholm

Heft 6 Jahrgang LVIII. 1926 Archiv ihr Molluskenkonde Beiträge zur Kenntnis der paläarktischen Planorbidae. Von W. A. Lindholm. I. Zur Synonymie des Planorbis crista (L.). Es ist eine bekannte Tatsache, daß unser kleinster Planorbis hinsichtlich der Skulptur seines Gehäuses verschiedene Varietäten darstellt, welche Eigenschaft ihm im Laufe der Zeiten eine stattliche Anzahl von Artnamen eingebracht hat. Es hatte lange gedauert, bis sich die Forscher überzeugt hatten, daß es sich nicht um mehrere Arten, sondern nur um Formen und z. T. sogar um Wachstumserscheinungen einer einzigen Art handelt. Es kommen eigentlich' nur zwei Formen in Betracht: eine glatte d. h. nur feingestreifte, nicht quer- gerippte, welche meist von den Autoren bis auf den heutigen Tag als PL nautileus (L.) und eine mit ian der Peripherie höckerartig vortretenden Querrippen versehene, welche als PL crista (L.) oder PL cristatus D rap , aufgeführt wird, und deren Jugendtracht an der Peripherie des letzten Umgangs mehr weniger lange Stacheln auf weist. Diese Jugendtracht bewahren ein zelne Individuen auch während ihrer weiteren Lebens dauer; solche Stücke sind von S. CI es sin als PL crista var. spinulosus in die Wissenschaft eingeführt worden. 242 Nun beruht diese landläufige Nomenklatur auf einen Irrtum, da Linné beide erwähnte Artnamen1) auf dasselbe Tier oder richtiger auf dieselbe Abbildung bei Rösel* 2) begründet hatte. Diese Figur stellt nun diejenige Form dar, welche dessin als var. spinulosus bezeichnet hatte, was schon aus RöseFs Worten her vorgeht: ,,Dieses Ammonshorn ist nicht nur gleichsam mit Reifen umleget, sondern es hat auch an seinem Rucken auf jedem Reif eines Stachelspitze.“ Die durch Linné vorgenommene doppelte Benennung dieser Art war seinen Zeitgenossen nicht entgangen, ist aber in unseren Tagen anscheinend vergessen worden. -

Land Snails and Soil Calcium in a Central Appalachian Mountain

Freshwater Snail Inventory of the Fish River Lakes 2/2012 Report for MOHF Agreement Number CT09A 2011 0605 6177 by Kenneth P. Hotopp Appalachian Conservation Biology PO Box 1298, Bethel, ME 04217 for the Maine Outdoor Heritage Fund 37 Wiscasset Rd. Pittston, ME 04345 Freshwater Snail Inventory of the Fish River Lakes Abstract Freshwater snails were inventoried at the eight major lakes of the Fish River watershed, Aroostook County, Maine, with special attention toward pond snails (Lymnaeidae) collected historically by regional naturalist Olof Nylander. A total of fourteen freshwater snail species in six families were recovered. The pond snail Stagnicola emarginatus (Say, 1821) was found at Square Lake, Eagle Lake, and Fish River Lake, with different populations exhibiting regional shell forms as observed by Nylander, but not found in three other lakes previously reported. More intensive inventory is necessary for confirmation. The occurrence of transitional shell forms, and authoritative literature, do not support the elevation of the endemic species Stagnicola mighelsi (W.G. Binney, 1865). However, the infrequent occurrence of S. emarginatus in all of its forms, and potential threats to this species, warrant a statewide assessment of its habitat and conservation status. Otherwise, a qualitative comparison with the Fish River Lakes freshwater snail fauna of 100 years ago suggests it remains mostly intact today. 1 Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................ 1 -

Phragmites Australis) Invasion and Glyphosate and Imazapyr Herbicide Application on Gastropod and Epiphyton Communities in Sheldon Marsh Nature Reserve

Effects of Common Reed (Phragmites australis) Invasion and Glyphosate and Imazapyr Herbicide Application on Gastropod and Epiphyton Communities in Sheldon Marsh Nature Reserve. A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christina L. Back B.S. Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology. The Ohio State University 2010 Master‟s Examination Committee: Dr. Joseph R. Holomuzki, Advisor Dr. Stuart A. Ludsin Dr. G. Thomas Watters Copyright by Christina L Back 2010 Abstract Phragmites australis, the common reed, is an invasive macrophyte in many eastern North American wetlands. Reed often rapidly forms dense, near-monotypic stands by replacing native vegetation, which lowers plant diversity and alters wetland habitat structure. Accordingly, herbicides such as imazypr-based Habitat® and glyphosate-based AquaNeat® are often applied to reed stands in an attempt to control its establishment and spread. Although these herbicides are apparently not toxic to benthic organisms, they may indirectly affect them by altering available habitat structure via increased detrital litter, increased light penetration to surface waters and increased water temperature. Understanding the impacts of widespread herbiciding on benthic communities, as well as the impact of different herbicides on habitat conditions, should help wetland managers design control plans to reduce reed and conserve system biodiversity. I compared gastropod (i.e., snails) and epiphyton communities, and habitat conditions among large, replicated plots of unsprayed Phragmites, glyphosate-sprayed Phragmites, imazapyr-sprayed Phragmites and unsprayed Typha angustifolia (narrow- leaf cattail) in early the summer 2008 in a Lake Erie coastal marsh. -

A Note on Oviposition by Lymnaea Stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Lymnaeidae) on Shells of Conspecifics Under Laboratory Conditions

Folia Malacol. 25(2): 101–108 https://doi.org/10.12657/folmal.025.007 A NOTE ON OVIPOSITION BY LYMNAEA STAGNALIS (LINNAEUS, 1758) (GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: LYMNAEIDAE) ON SHELLS OF CONSPECIFICS UNDER LABORATORY CONDITIONS PAOLA LOMBARDO1*, FRANCESCO PAOLO MICCOLI2 1 Limno Consulting, via Bedollo 303, I-00124 Rome, Italy (e-mail: [email protected]) 2 University of L’Aquila, Coppito Science Center, I-67100 L’Aquila, Italy (e-mail: [email protected]) *corresponding author ABSTRACT: Oviposition by Lymnaea stagnalis (L.) on shells of conspecifics has been reported anecdotally from laboratory observations. In order to gain the first quantitative insight into this behaviour, we have quantified the proportion of individuals bearing egg clutches in a long-term monospecific outdoor laboratory culture of L. stagnalis during two consecutive late-summer months. The snails were assigned to size classes based on shell height. Differences between the size class composition of clutch-bearers and of the general population were statistically compared by means of Pearson’s distance χ²P analysis. Egg clutches were laid on snails of shell height >15 mm (i.e. reproductive-age individuals), with significant selection for the larger size classes (shell height 25–40 mm). While the mechanisms of and reasons behind such behaviour remain unknown, selection of larger adults as egg-carriers may have ecological implications at the population level. KEY WORDS: freshwater gastropods, Lymnaea stagnalis, great pond snail, reproductive behaviour INTRODUCTION Lymnaea stagnalis (Linnaeus, 1758) is a common & CARRIKER 1946, TER MAAT et al. 1989, ELGER & Holarctic freshwater gastropod, inhabiting most of LEMOINE 2005, GROSS & LOMBARDO in press). -

North American Hydrobiidae (Gastropoda: Rissoacea): Redescription and Systematic Relationships of Tryonia Stimpson, 1865 and Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886

THE NAUTILUS 101(1):25-32, 1987 Page 25 . North American Hydrobiidae (Gastropoda: Rissoacea): Redescription and Systematic Relationships of Tryonia Stimpson, 1865 and Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886 Robert Hershler Fred G. Thompson Department of Invertebrate Zoology Florida State Museum National Museum of Natural History University of Florida Smithsonian Institution Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Washington, DC 20560, USA ABSTRACT scribed) in the Southwest. Taylor (1966) placed Tryonia in the Littoridininae Taylor, 1966 on the basis of its Anatomical details are provided for the type species of Tryonia turreted shell and glandular penial lobes. It is clear from Stimpson, 1865, Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886, Fonteli- cella Gregg and Taylor, 1965, and Microamnicola Gregg and the initial descriptions and subsequent studies illustrat- Taylor, 1965, in an effort to resolve the systematic relationships ing the penis (Russell, 1971: fig. 4; Taylor, 1983:16-25) of these taxa, which represent most of the generic-level groups that Fontelicella and its subgenera, Natricola Gregg and of Hydrobiidae in southwestern North America. Based on these Taylor, 1965 and Microamnicola Gregg and Taylor, 1965 and other data presented either herein or in the literature, belong to the Nymphophilinae Taylor, 1966 (see Hyalopyrgus Thompson, 1968 is assigned to Tryonia; and Thompson, 1979). While the type species of Pyrgulop- Fontelicella, Microamnicola, Nat ricola Gregg and Taylor, 1965, sis, P. nevadensis (Stearns, 1883), has not received an- Marstonia F. C. Baker, 1926, and Mexistiobia Hershler, 1985 atomical study, the penes of several eastern species have are allocated to Pyrgulopsis. been examined by Thompson (1977), who suggested that The ranges of both Tryonia and Pyrgulopsis include parts the genus may be a nymphophiline. -

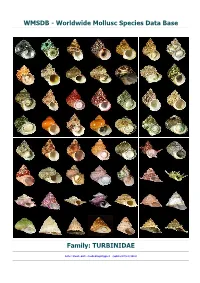

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Gastropoda, Pleuroceridae), with Implications for Pleurocerid Conservation

Zoosyst. Evol. 93 (2) 2017, 437–449 | DOI 10.3897/zse.93.14856 museum für naturkunde Genetic structuring in the Pyramid Elimia, Elimia potosiensis (Gastropoda, Pleuroceridae), with implications for pleurocerid conservation Russell L. Minton1, Bethany L. McGregor2, David M. Hayes3, Christopher Paight4, Kentaro Inoue5 1 Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Houston Clear Lake, 2700 Bay Area Boulevard MC 39, Houston, Texas 77058 USA 2 Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, 200 9th Street SE, Vero Beach, Florida 32962 USA 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Eastern Kentucky University, 521 Lancaster Avenue, Richmond, Kentucky 40475 USA 4 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Rhode Island, 100 Flagg Road, Kingston, Rhode Island 02881 USA 5 Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute, 578 John Kimbrough Boulevard, 2260 TAMU, College Station, Texas 77843 USA http://zoobank.org/E6997CB6-F054-4563-8C57-6C0926855053 Corresponding author: Russell L. Minton ([email protected]) Abstract Received 7 July 2017 The Interior Highlands, in southern North America, possesses a distinct fauna with nu- Accepted 19 September 2017 merous endemic species. Many freshwater taxa from this area exhibit genetic structuring Published 15 November 2017 consistent with biogeography, but this notion has not been explored in freshwater snails. Using mitochondrial 16S DNA sequences and ISSRs, we aimed to examine genetic struc- Academic editor: turing in the Pyramid Elimia, Elimia potosiensis, at various geographic scales. On a broad Matthias Glaubrecht scale, maximum likelihood and network analyses of 16S data revealed a high diversity of mitotypes lacking biogeographic patterns across the range of E. -

The Malacological Society of London

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This meeting was made possible due to generous contributions from the following individuals and organizations: Unitas Malacologica The program committee: The American Malacological Society Lynn Bonomo, Samantha Donohoo, The Western Society of Malacologists Kelly Larkin, Emily Otstott, Lisa Paggeot David and Dixie Lindberg California Academy of Sciences Andrew Jepsen, Nick Colin The Company of Biologists. Robert Sussman, Allan Tina The American Genetics Association. Meg Burke, Katherine Piatek The Malacological Society of London The organizing committee: Pat Krug, David Lindberg, Julia Sigwart and Ellen Strong THE MALACOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON 1 SCHEDULE SUNDAY 11 AUGUST, 2019 (Asilomar Conference Center, Pacific Grove, CA) 2:00-6:00 pm Registration - Merrill Hall 10:30 am-12:00 pm Unitas Malacologica Council Meeting - Merrill Hall 1:30-3:30 pm Western Society of Malacologists Council Meeting Merrill Hall 3:30-5:30 American Malacological Society Council Meeting Merrill Hall MONDAY 12 AUGUST, 2019 (Asilomar Conference Center, Pacific Grove, CA) 7:30-8:30 am Breakfast - Crocker Dining Hall 8:30-11:30 Registration - Merrill Hall 8:30 am Welcome and Opening Session –Terry Gosliner - Merrill Hall Plenary Session: The Future of Molluscan Research - Merrill Hall 9:00 am - Genomics and the Future of Tropical Marine Ecosystems - Mónica Medina, Pennsylvania State University 9:45 am - Our New Understanding of Dead-shell Assemblages: A Powerful Tool for Deciphering Human Impacts - Sue Kidwell, University of Chicago 2 10:30-10:45 -

Download Preprint

1 Mobilising molluscan models and genomes in biology 2 Angus Davison1 and Maurine Neiman2 3 1. School of Life Sciences, University Park, University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK 4 2. Department of Biology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA and Department of Gender, 5 Women's, and Sexuality Studies, University of Iowa, Iowa, City, IA, USA 6 Abstract 7 Molluscs are amongst the most ancient, diverse, and important of all animal taxa. Even so, 8 no individual mollusc species has emerged as a broadly applied model system in biology. 9 We here make the case that both perceptual and methodological barriers have played a role 10 in the relative neglect of molluscs as research organisms. We then summarize the current 11 application and potential of molluscs and their genomes to address important questions in 12 animal biology, and the state of the field when it comes to the availability of resources such 13 as genome assemblies, cell lines, and other key elements necessary to mobilising the 14 development of molluscan model systems. We conclude by contending that a cohesive 15 research community that works together to elevate multiple molluscan systems to ‘model’ 16 status will create new opportunities in addressing basic and applied biological problems, 17 including general features of animal evolution. 18 Introduction 19 Molluscs are globally important as sources of food, calcium and pearls, and as vectors of 20 human disease. From an evolutionary perspective, molluscs are notable for their remarkable 21 diversity: originating over 500 million years ago, there are over 70,000 extant mollusc 22 species [1], with molluscs present in virtually every ecosystem. -

Empirically Derived Indices of Biotic Integrity for Forested Wetlands, Coastal Salt Marshes and Wadable Freshwater Streams in Massachusetts

Empirically Derived Indices of Biotic Integrity for Forested Wetlands, Coastal Salt Marshes and Wadable Freshwater Streams in Massachusetts September 15, 2013 This report is the result of several years of field data collection, analyses and IBI development, and consideration of the opportunities for wetland program and policy development in relation to IBIs and CAPS Index of Ecological Integrity (IEI). Contributors include: University of Massachusetts Amherst Kevin McGarigal, Ethan Plunkett, Joanna Grand, Brad Compton, Theresa Portante, Kasey Rolih, and Scott Jackson Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management Jan Smith, Marc Carullo, and Adrienne Pappal Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection Lisa Rhodes, Lealdon Langley, and Michael Stroman Empirically Derived Indices of Biotic Integrity for Forested Wetlands, Coastal Salt Marshes and Wadable Freshwater Streams in Massachusetts Abstract The purpose of this study was to develop a fully empirically-based method for developing Indices of Biotic Integrity (IBIs) that does not rely on expert opinion or the arbitrary designation of reference sites and pilot its application in forested wetlands, coastal salt marshes and wadable freshwater streams in Massachusetts. The method we developed involves: 1) using a suite of regression models to estimate the abundance of each taxon across a gradient of stressor levels, 2) using statistical calibration based on the fitted regression models and maximum likelihood methods to predict the value of the stressor metric based on the abundance of the taxon at each site, 3) selecting taxa in a forward stepwise procedure that conditionally improves the concordance between the observed stressor value and the predicted value the most and a stopping rule for selecting taxa based on a conditional alpha derived from comparison to pseudotaxa data, and 4) comparing the coefficient of concordance for the final IBI to the expected distribution derived from randomly permuted data. -

Species Status Assessment Report for Beaverpond Marstonia

Species Status Assessment Report For Beaverpond Marstonia (Marstonia castor) Marstonia castor. Photo by Fred Thompson Version 1.0 September 2017 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4 Atlanta, Georgia 1 2 This document was prepared by Tamara Johnson (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Georgia Ecological Services Field Office) with assistance from Andreas Moshogianis, Marshall Williams and Erin Rivenbark with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southeast Regional Office, and Don Imm (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Georgia Ecological Services Field Office). Maps and GIS expertise were provided by Jose Barrios with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southeast Regional Office. We appreciate Gerald Dinkins (Dinkins Biological Consulting), Paul Johnson (Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources), and Jason Wisniewski (Georgia Department of Natural Resources) for providing peer review of a prior draft of this report. 3 Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Species status assessment report for beaverpond marstonia. Version 1.0. September, 2017. Atlanta, GA. 24 pp. 4 Species Status Assessment Report for Beaverpond Marstonia (Marstonia castor) Prepared by the Georgia Ecological Services Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment is a comprehensive biological status review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) for beaverpond marstonia (Marstonia castor), and provides a thorough account of the species’ overall viability and extinction risk. Beaverpond marstonia is a small spring snail found in tributaries located east of Lake Blackshear in Crisp, Worth, and Dougherty Counties, Georgia. It was last documented in 2000. Based on the results of repeated surveys by qualified species experts, there appears to be no extant populations of beaverpond marstonia. -

Invertebrates

State Wildlife Action Plan Update Appendix A-5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Fact Sheets INVERTEBRATES Conservation Status and Concern Biology and Life History Distribution and Abundance Habitat Needs Stressors Conservation Actions Needed Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 2015 Appendix A-5 SGCN Invertebrates – Fact Sheets Table of Contents What is Included in Appendix A-5 1 MILLIPEDE 2 LESCHI’S MILLIPEDE (Leschius mcallisteri)........................................................................................................... 2 MAYFLIES 4 MAYFLIES (Ephemeroptera) ................................................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Cinygmula gartrelli) .................................................................................................................... 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia falcula) ............................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia jenseni) ............................................................................................................ 4 [unnamed] (Siphlonurus autumnalis) .............................................................................................................. 4 [unnamed] (Cinygmula gartrelli) .................................................................................................................... 4 [unnamed] (Paraleptophlebia falcula) ...........................................................................................................