Harry Compton, an Enslaved And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igneous Processes During the Assembly and Breakup of Pangaea: Northern New Jersey and New York City

IGNEOUS PROCESSES DURING THE ASSEMBLY AND BREAKUP OF PANGAEA: NORTHERN NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK CITY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AND FIELD GUIDE EDITED BY Alan I. Benimoff GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY XXX ANNUAL CONFERENCE AND FIELDTRIP OCTOBER 11 – 12, 2013 At the College of Staten Island, Staten Island, NY IGNEOUS PROCESSES DURING THE ASSEMBLY AND BREAKUP OF PANGAEA: NORTHERN NEW JERSEY AND NEW YORK CITY CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS AND FIELD GUIDE EDITED BY Alan I. Benimoff GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY XXX ANNUAL CONFERENCE AND FIELDTRIP OCTOBER 11 – 12, 2013 COLLEGE OF STATEN ISLAND, STATEN ISLAND, NY i GEOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY 2012/2013 EXECUTIVE BOARD President .................................................. Alan I. Benimoff, PhD., College of Staten Island/CUNY Past President ............................................... Jane Alexander PhD., College of Staten Island/CUNY President Elect ............................... Nurdan S. Duzgoren-Aydin, PhD., New Jersey City University Recording Secretary ..................... Stephen J Urbanik, NJ Department of Environmental Protection Membership Secretary ..............................................Suzanne Macaoay Ferguson, Sadat Associates Treasurer ............................................... Emma C Rainforth, PhD., Ramapo College of New Jersey Councilor at Large………………………………..Alan Uminski Environmental Restoration, LLC Councilor at Large ............................................................ Pierre Lacombe, U.S. Geological Survey Councilor at Large ................................. -

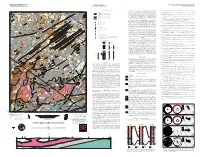

Bedrock Geologic Map of the Monmouth Junction Quadrangle, Water Resources Management U.S

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Prepared in cooperation with the BEDROCK GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MONMOUTH JUNCTION QUADRANGLE, WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SOMERSET, MIDDLESEX, AND MERCER COUNTIES, NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL AND WATER SURVEY NATIONAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROGRAM GEOLOGICAL MAP SERIES GMS 18-4 Cedar EXPLANATION OF MAP SYMBOLS cycle; lake level rises creating a stable deep lake environment followed by a fall in water level leading to complete Cardozo, N., and Allmendinger, R. W., 2013, Spherical projections with OSXStereonet: Computers & Geosciences, v. 51, p. 193 - 205, doi: 74°37'30" 35' Hill Cem 32'30" 74°30' 5 000m 5 5 desiccation of the lake. Within the Passaic Formation, organic-rick black and gray beds mark the deep lake 10.1016/j.cageo.2012.07.021. 32 E 33 34 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 490 000 FEET 542 40°30' 40°30' period, purple beds mark a shallower, slightly less organic-rich lake, and red beds mark a shallow oxygenated 6 Contacts 100 M Mettler lake in which most organic matter was oxidized. Olsen and others (1996) described the next longer cycle as the Christopher, R. A., 1979, Normapolles and triporate pollen assemblages from the Raritan and Magothy formations (Upper Cretaceous) of New 6 A 100 I 10 N Identity and existance certain, location accurate short modulating cycle, which is made up of five Van Houten cycles. The still longer in duration McLaughlin cycles Jersey: Palynology, v. 3, p. 73-121. S T 44 000m MWEL L RD 0 contain four short modulating cycles or 20 Van Houten cycles (figure 1). -

New York City Adventure 2103 for on Line Event Info

New York City Adventure Friday, October 11, 2013 Departing Boon Center at 11:30 Tickets: $40 (Includes transportation, lunch, tour, and dinner) The New Home of Nyack College and Alliance Theological Seminary We have made the official move to our new home in New York City this fall after signing a lease with options that extends to 2042, at 2 Washington Street in Lower Manhattan’s Battery Park. "Nyack's roots as a leader in Christian higher education were planted in New York City more than 130 years ago. Moving to the financial hub of this gateway city to the world will help us reach our goal of becoming a world class institution of higher education,” said Dr. Michael Scales , president of Nyack College. “We are committed to providing our growing student population with the best learning environment possible, which includes access to career opportunities in the heart of New York City.” Battery Park Named for the battery of cannons that protected the harbor. From the waters edge, the Dutch, British and Americans all protected Manhattan against possible attack or invasion. The modern, 25-acre park is mostly landfill. Within Battery Park can be found numerous memorials, the ferries to Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty as well as Castle Clinton . Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House The Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House was designed by Cass Gilbert and built between 1902 and 1907. It is a glorious Beaux-Arts building with four large sculptures in front designed by Daniel Chester French. It was originally built to house the import duty operations for the port of New York. -

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

Early New York Houses (1900)

1 f A ':-- V ,^ 4* .£^ * '"W "of o 5 ^/ v^v %-^v V^\^ ^^ > . V .** .-•jfltef-. %.^ .-is»i-. \.^ .-^fe-. *^** -isM'. \,/ V s\ " c«^W.».' . o r^0^ a? %<> **' -i v , " • S » < •«. ci- • ^ftl>a^'» ( c 'f ^°- ^ '^#; > ^ " • 1 * ^5- «> w * dsf\\Vv>o», . O V ^ V u 4- ^ ° »*' ^> t*o* **d« vT1 *3 ^d* 4°^ » " , ^o .<4 o ^iW/^2, , ^A ^ ^°^ fl <^ ° t'o LA o^ t « « % 1 75*° EARLY Z7Ja NEW YORK HOVSEvS 1900 EARLY NEW YORK HOVSES WITH HISTORICAL 0^ GEN- EALOGICAL NOTES BY' WILLIAM S.PELLETREAV,A.M. PHOTOGRAPHS OFOLDHOVSES C-ORIGINAL ILLVSTRATIONSBY C.G.MOLLER. JR. y y y v v v v v v v <&-;-??. IN TEN PARTS FRANCIS P.HARPER, PVBLIS HER NEW YORK,A.D.jQOO^ * vvvvvvvv 1A Library of Coi NOV 13 1900 SECOND COPY Oeliv. ORDER DIVISION MAR. 2 1901 fit,* P3b ..^..^•^•^Si^jSb;^^;^^. To the memory of WILLIAM KELBY I^ate librarian of the New York Historical Society f Whose labors of careful patient and successful research w have been equalled by few—surpassed by none. w Natvs, Decessit, MDCCCXU MDCCCXCVIII ¥ JIT TIBI TERRA LEVIJ , ^5?^5?^'55>•^••^•^=^,•^•" ==i•'t=^^•':ft>•' 1 St. Phuup's Church, Centre; Street Page 1 V 2 Old Houses on " Monkey Hill " 3/ 3 The Oldest Houses in Lafayette Place 7 / 4 The Site of Captain Kidd's House ll • 5 Old Houses on York Street 15/ 6 The Merchant's Exchange 19 V 7 Old Houses Corner of Watts and Hudson Streets 23 </ 27v/ 8 Baptist Church on Fayette Street, 1808 . 9 The in Night Before Christmas" was House which "The •/ Written 31 10 Franklin Square, in 1856 35^ 11 The First Tammany Hall 41 </ 12 Houses on Bond Street 49^ 13 The Homestead of Casper Samler 53/ 14 The Tank of the Manhattan Water Company 57 ^ 15 Residence of General Winfield Scott 61 l/ 16 The Last Dwelling House on Broadway, (The Goelet Mansion) 65^ \/ 17 Old Houses on Cornelia Street , n 18 The Last of LE Roy Place 75*/ 19 Northeast Corner of Fifth Avenue and Sixteenth Street . -

Spring 2021 Newsletter

Spring | 2021 New Jersey Conservation FINDING PEACE in the PANDEMIC Getting outdoors for body and mind PIPELINE CASE HEADS TO U.S. SUPREME COURT 10 High court will decide if private PennEast company can seize public lands to build a for‐profit pipeline. SOMEWHERE, OVER THE RAINBOW 12 Rainbow Hill at Sourland Mountain Preserve offers sweeping views, including rainbows after storms! TEN MILE TRAIL VISION REALIZED 14 Newly‐preserved land helps connect 1,200 acres of open space and farmland in Hunterdon County. ABOUT THE COVER “During the pandemic this past year, being outdoors in natural surroundings simply felt nice, sane, and free.” MaryAnn Ragone DeLambily took this stunning photo while hiking through Franklin Parker Preserve, one of the many places New Jerseyans found solace over the past year. Trustees Rosina B. Dixon, M.D. HONORARY TRUSTEES PRESIDENT Hon. James J. Florio Wendy Mager FIRST VICE PRESIDENT Hon. Thomas H. Kean Joseph Lemond Hon. Maureen Ogden SECOND VICE PRESIDENT Hon. Christine Todd Whitman Finn Caspersen, Jr. TREASURER From Our Pamela P. Hirsch SECRETARY Executive Director ADVISORY COUNCIL Penelope Ayers ASSISTANT SECRETARY Bradley M. Campbell Michele S. Byers Cecilia Xie Birge Christopher J. Daggett Jennifer Bryson Wilma Frey Roger Byrom John D. Hatch Theodore Chase, Jr. Douglas H. Haynes It seems like we all need inspiration and hope this year given the not‐over‐yet pandemic, Jack Cimprich H. R. Hegener David Cronheim Hon. Rush D. Holt climate change, species extinction, tribalism, isolation and the news! Getting outdoors is one John L. Dana Susan L. Hullin way to find “Peace in the Pandemic” as you can read about in the pages that follow. -

2020 Natural Resources Inventory

2020 NATURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY TOWNSHIP OF MONTGOMERY SOMERSET COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Prepared By: Tara Kenyon, AICP/PP Principal NJ License #33L100631400 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 5 AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN AND AROUND MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP ...................................................... 7 REGULATIONS AND PROGRAMS RELATED TO AGRICULTURE ...................................................................... 11 HEALTH IMPACTS OF AGRICULTURAL AVAILABILITY AND LOSS TO HUMANS, PLANTS AND ANIMALS .... 14 HOW IS MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP WORKING TO SUSTAIN AND ENHANCE AGRICULTURE? ................... 16 RECOMMENDATIONS AND POTENTIAL PROJECTS .......................................................................................... 18 CITATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 19 AIR QUALITY .............................................................................................................................................................. 21 CHARACTERISTICS OF AIR .................................................................................................................................. 21 -

Land, Natural Resources, and Geology

Land and Natural Resources of West Amwell By Fred Bowers, Ph.D Goat Hill from the north Diabase Boulders are common. Shale and Argillite outcrops appear like this. General Description of the Area West Amwell Township is in Hunterdon County, New Jersey, USA. It is a 22 square mile rural township with just over 2200 people, located near Lambertville, New Jersey. It is one of the more scenic parts of the New Jersey Piedmont. It is identified in red on the maps below. West Amwell is characterized by most people as a "rocky land." One of the oldest villages in the township is called Rocktown. If you visit or look around the township, you cannot avoid seeing rocks and outcrops like those pictured above. Hunterdon County New Jersey, with West Amwell located at the southern border, marked in red The physiographic provinces of New Jersey, with Hunterdon County and West Amwell marked in red Rocks The backbone of West Amwell Township's land is the Sourland Mountain; a typical Piedmont ridge formed by a very hard igneous rock called diabase or "Trap Rock." The Sourland Mountain ends at the Delaware River below Goat Hill which you see in the picture above, looking south from the Lambertville toll bridge. To the south and north of the diabase, shale and argillite occurs, and these rocks form the lower lands we know of as Pleasant Valley and the shale ridges and valleys you see from around Mt. Airy. In order to appreciate the rocks and the influence they have on the look of the land, it is useful to have a short review of rocks. -

FRAUNCES TAVERN BLOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT, Borough of Manhattan

FRAUNCES TAVERN BLOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION REPORT 1978 City of New York Edward I . Koch, Mayor Landmarks Preservation Commission Kent L. Barwick, Chairman Morris Ketchum, Jr., Vice Chairman Commissioners R. Michael Brown Thomas J. Evans Elisabeth Coit James Marston Fitch George R. Collins Marie V. McGovern William J. Conklin Beverly Moss Spatt FRAUNCES TAVERN BLOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT 66 - c 22 Water DESIGNATED NOV. 14, 1978 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION., COMMISSION FTB-HD Landmarks Preservation Commission November 14, 1978, Designation List 120 LP-0994 FRAUNCES TAVERN BLOCK HISTORIC DISTRICT, Borough of Manhattan BOUNDARIES The property bounded by the southern curb line of Pearl Street, the western curb line of Coenties Slip, the northern curb line of Water Street, and the eastern curb line of Broad Street, Manhattan. TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING On March 14, 1978, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on this area which is now proposed as an Historic District (Item No. 14). Three persons spoke in favor of the proposed designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. -1 FTB-HD Introduction The Fre.unces Tavern Block Historic District, bounded by Fearl, Broad, and Water Streets, and Coenties Slip, stands today as a vivid reminder of the early history and development of this section of Manhattan. Now a single block of low-rise commercial buildings dating from the 19th century--with the exception of the 18th-century Fraunces Tavern--it contrasts greatly with the modern office towers surrounding it. The block, which was created entirely on landfill, was the first extension of the Manhattan shoreline for commercial purposes, and its development involved some of New York's most prominent families. -

THE NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY Quarterly Bulletin

THE NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY Quarterly Bulletin VOLUME XXIII JULY, 1939 NUMBER THREE POOL IN THE SOCIETY'S GARDEN WITH ANNA HYATT HUNTINGTON'S "DIANA OF THE CHASE" Gift of a Member of the Society, 1939 UBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY AND ISSUED TO MEMBERS Mew York: iyo Central Park West HOURS 0 THE ART GALLERIES AND MUSEUM Open free to the public daily except Monday. Weekdays: from 10 A.M. to 5 P.M. Sundays and holidays from 1 to 5 P.M. THE LIBRARY Open daily except Sunday from 9 A.M. to 5 P.M. Holidays: from 1 to 5 P.M. HOLIDAYS The Art Galleries, Museum, and Library are open on holidays from* 1 to 5 P.M., except on New Year's Day, July Fourth, Thanksgiving, and Christmas, when the building is closed. EGYPTIAN COLLECTIONS The Egyptian Collections of The New-York Historical Society are on exhibition daily in the Brooklyn Museum, Eastern Parkway and Washington Avenue, Brooklyn, N. Y. Open weekdays, from 10 to 5; Sundays, from 2 to 6. Free, except Mondays and Fridays. THE NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY, 170 CENTRAL PARK WEST John Jfted OJtekes 1856-1959 T is with profound sorrow that the Society records the death in New York City on May 4, 1939, of Mr. John I Abeel Weekes, President of the Society from 1913 to April, 1939. Mr. Weekes was born at Oyster Bay, Long Island, July 24, 1856, son of John Abeel Weekes and Alice Howland Delano, his wife, and grandson of Robert Doughty Weekes, first president of the New York Stock Exchange. -

Settings Report for the Central Delaware Tributaries Watershed Management Area 11

Settings Report for the Central Delaware Tributaries Watershed Management Area 11 02 03 05 01 04 06 07 08 11 09 10 12 20 19 18 13 14 17 15 16 Prepared by: The Regional Planning Partnership Prepared for: NJDEP October 15, 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v List of Tables vi Acknowledgements vii 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 Importance of Watershed Planning 1 3.0 Significance of the Central Delaware Tributaries 2 4.0 Physical and Ecological Characteristics 4.1 Location 2 4.2 Physiography and Soils 3 4.3 Surface Water Hydrology 4 4.3.1 Hakihokake/Harihokake/Nishisakawick Creeks 5 4.3.2 Lockatong/Wickecheoke Watershed 6 4.3.3 Alexauken/Moores/Jacobs Watershed 6 4.3.4 Assunpink Creek Above Shipetaukin Creek 7 4.3.5 Assunpink Below Shipetaukin Creek 7 4.4 Land Use/Land Cover 9 4.4.1 Agricultural Land 9 4.4.2 Forest Land 11 4.4.3 Urban and Built Land 12 4.4.4 Wetlands 12 4.4.5 Water 14 4.4.6 Barren Lands 14 4.5 Natural Resource Priority Habitat 14 5.0 Surface Water Quality 5.1 Significance of Streams and Their Corridors 15 5.2 Federal Clean Water Act Requirements for Water Quality in New Jersey 15 5.3 Surface Water Quality Standards 16 5.4 Surface Water Quality Monitoring 18 i TABLE OF CONTENTS 5.4.1 Monitoring Stations in the Central Delaware Tributaries 18 5.5 Surface Water Quality in the Hakihokake/Harihokake/ Nishisakawick 5.5.1 Chemical and Sanitary Water Quality 19 5.5.2 Biological Evaluation 19 5.6 Surface Water Quality in the Lockatong/Wickecheoke Watershed 5.6.1 Chemical and Sanitary Water Quality 20 5.6.2 Biological Evaluation 20 5.7 -

Sourland Mountain Preserve

About Sourland Mountain Preserve Sourland Mountain Preserve Trail Information Sourland Mountain The name “Sourlands” is derived from the fact Location: Sourland Mountain is located in Main Trail: The main trail in Sourland that early settlers found the rocky soils difficult East Amwell Township, in the southeastern Mountain Preserve is very wide and flat, with Preserve to farm. The limited supply of groundwater section of Hunterdon County. There is a a short uphill slope at the end. The trail winds saved the forest from destruction by small parking area at 233 Rileyville Road, through a beautiful deciduous forest, strewn developers. Its woodlands shelter a very rich Ringoes 08551. Please note: No restrooms with large boulders. Along this trail is a Trail Map and Guide and diverse native plant community. facilities are available. floodplain with a rich diversity of aquatic life. Directions from the Flemington Area: Yellow Trail: This trail branches off the Main The park’s 388 acres are comprised of a Trail, about a quarter of a mile from the deciduous forest with a swamp surrounded by Take Route 202/31 south from the Flemington Circle for 5 miles to the jug handle for parking area. It can be a very wet trail and two streams. Formed almost 200 million years crosses a small stream where hikers must rock ago, the rocks of the Sourlands, called diabase Wertsville Road (Route 602). Use the traffic light to cross over Route 202/31. Continue on hop. In spring, many wildflowers can be or “trap rock,” were used to produce railroad found along this trail.