File 4 P. 48 • My Super Dense Crush Load Commute Every Morning I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Rail Capacity

69719 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Transport Capacity Analysis Procedures for Developing Cities Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Jack Reilly and Herbert Levinson September, 2011 World Bank, Transport Research Support Program, TRS Public Disclosure Authorized With Support from UK Department for International Development 1 The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of a number of people in the development of this manual. Particular among these were Sam Zimmerman, consultant to the World Bank and Mr. Ajay Kumar, the World Bank project manager. We also benefitted greatly from the insights of Dario Hidalgo of EMBARQ. Further, we acknowledge the work of the staff of Transmilenio, S.A. in Bogota, especially Sandra Angel and Constanza Garcia for providing operating data for some of these analyses. A number of analyses in this manual were prepared by students from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. These include: Case study – Bogota Ivan Sanchez Case Study – Medellin Carlos Gonzalez-Calderon Simulation modeling Felipe Aros Vera Brian Maleck Michael Kukesh Sarah Ritter Platform evacuation Kevin Watral Sample problems Caitlynn Coppinger Vertical circulation Robyn Marquis Several procedures and tables in this report were adapted from the Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual, published by the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC. Public Transport Analysis Procedures for Developing Cities 2 Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................... -

MDTA Metromover Extensions Transfer Analysis Final Technical Memorandum 3, April 1994

Center for Urban Transportation Research METRO-DADE TRANSIT AGENCY MDTA Metromover Extensions Transfer Analysis FINAL Technical Memorandum Number 3 Analysis of Impacts of Proposed Transfers Between Bus and Mover CUllR University of South Florida College of Engineering (Cf~-~- METRO-DADE TRANSIT AGENCY MDTA Metromover Extensions Transfer Analysis FINAL Technical Memorandum Number 3 Analysis of Impacts of Proposed Transfers Between Bus and Mover Prepared for Metro-Dade.. Transit Agency lft M E T R 0 D A D E 1 'I'··.·-.·.· ... .· ','··-,·.~ ... • R,,,.""' . ,~'.'~:; ·.... :.:~·-·· ,.,.,.,_, ,"\i :··-·· ".1 •... ,:~.: .. ::;·~·~·;;·'-_i; ·•· s· .,,.· - I ·1· Prepared by Center for Urban Transportation Research College of Engineering University of South Florida Tampa, Florida CUTR APRIL 1994 TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM NUMBER 3 Analysis of Impacts of Proposed Transfers between Bus and Mover Technical Memorandum Number 3 analyzes the impacts of the proposed transfers between Metrobus and the new legs of the Metromover scheduled to begin operation in late May 1994. Impacts on passengers walk distance from mover stations versus current bus stops, and station capacity will also be examined. STATION CAPACITY The following sections briefly describe the bus terminal/transfer locations for the Omni and Brickell Metromover Stations. Bus to mover transfers and bus route service levels are presented for each of the two Metromover stations. Figure 1 presents the Traffic Analysis Zones (TAZ) in the CBD, as well as a graphical representation of the Metromover alignment. Omni Station The Omni bus terminal adjacent to the Omni Metromover Station is scheduled to open along with the opening of the Metromover extensions in late May 1994. The Omni bus terminal/Metromover Station is bounded by Biscayne Boulevard, 14th Terrace, Bayshore Drive, and NE 15th Street. -

Transit Capacity and Quality of Service Manual (Part B)

7UDQVLW&DSDFLW\DQG4XDOLW\RI6HUYLFH0DQXDO PART 2 BUS TRANSIT CAPACITY CONTENTS 1. BUS CAPACITY BASICS ....................................................................................... 2-1 Overview..................................................................................................................... 2-1 Definitions............................................................................................................... 2-1 Types of Bus Facilities and Service ............................................................................ 2-3 Factors Influencing Bus Capacity ............................................................................... 2-5 Vehicle Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-5 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-13 Fundamental Capacity Calculations .......................................................................... 2-15 Vehicle Capacity................................................................................................... 2-15 Person Capacity..................................................................................................... 2-22 Planning Applications ............................................................................................... 2-23 2. OPERATING ISSUES............................................................................................ 2-25 Introduction.............................................................................................................. -

Load Quantification of the Wheel–Rail Interface of Rail Vehicles for The

Original Article Proc IMechE Part F: J Rail and Rapid Transit 0(0) 1–10 Load quantification of the wheel–rail ! IMechE 2016 Reprints and permissions: interface of rail vehicles for the sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0954409716684266 infrastructure of light rail, heavy rail, journals.sagepub.com/home/pif and commuter rail transit Xiao Lin, J Riley Edwards, Marcus S Dersch, Thomas A Roadcap and Conrad Ruppert Jr Abstract The type and magnitude of loads that pass through the track superstructure have a great impact on both the design and the performance of the concrete crossties and fastening systems. To date, the majority of North American research that focus on quantifying the rail infrastructure loading conditions has been conducted on heavy-haul freight railroads. However, the results and recommendations of these studies may not be applicable to the rail transit industry due to a variety of factors. Unlike the freight railroads, which have standardized maximum gross rail loads and superstructure design practices for vehicles, the rail transit industry is home to a significant variety of vehicle and infrastructure designs. Some of the current transit infrastructure design practices, which were established decades ago, need to be updated with respect to the current loading environment, infrastructure types, and understanding of the component and system-level behavior. This study focuses on quantifying the current load environment for light rail, heavy rail, and commuter rail transit infrastructure in the United States. As an initial phase of this study, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC) have conducted a literature review of different metrics, which is used to evaluate the static, dynamic, impact, and rail seat loads for the rail transit infrastructure. -

M-7 Long Island Railroad .Montreal EMU .Gallery Car Electric Multiple Unit -M- ~ New York, Usj

APPENDIX 6 . M-7 Long Island Railroad .Montreal EMU .Gallery Car Electric Multiple Unit -M- ~ New York, Usj Under joint agreement to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority / Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) and the Metro-North Railroad (MNR), Bombardier Transportation is providing Electric Multiple Unit (EMU) M- 7 commuter cars to LIRR to begin replacement of its Metropolitan M-I commuter car fleet. Chartered in 1834, the Long The units are equipped with The interior of the LIRR' Island Rail Road is the largest Bombardier's renowned stainless "Car of the Future" was designel Commuter Rail system in North steel carbodies for long life and with the input of the passenger America. low maintenance, and asynchro- and employees and includes a] nous AC motors featuring state- ADA compliant toilet, cellula Bombardier's new Electric of-the-art IGBT {isolated gate bipo- telephone and wide, single-lea Multiple Units, its first railcar lar transistors) inverters. Use of sliding doors for ease of entry an contract for the LIRR, will service outboard-bearing bolsterless fab- exit. the Long Island commuter lines, ricated bogies offers considerable constituting 80% of the system. weight savings over cast bogies. ~ BOMBARDIER BOMBARD" TRANSPORTATION 'V Electric Multiple Unit -M- 7 POWERCAR WITH TOILET ---10' 6' B END FEND I 3,200 mi , -: -" 0 C==- ~=0 :- CJCJ ~~[] CJCJCJCJCJCJ [] I D b 01 " ~) -1::1 1211-1/2 t~J ~~W ~~IL...I ~w -A'-'1~~~- I ~~ 309~mmt ~ 1 I~ 11 m 2205~16~m-! 591..1.6" mm --I I 1- -- 59°6" ° 4°8-1/2. , ~ 16,~:,60~m ~-- -;cl 10435mm ~ .-1 -

COMPREHENSIVE SYSTEM ANALYSIS | Volume II: Service Plan City of Minot

COMPREHENSIVE SYSTEM ANALYSIS | Volume II: Service Plan City of Minot City of Minot COMPREHENSIVE SYSTEM ANALYSIS Volume II: Service Plan December 2013 Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Associates Inc. | i COMPREHENSIVE SYSTEM ANALYSIS | Volume II: Service Plan City of Minot Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................1-1 Community Outreach ............................................................................................................................. 1-2 2 Vision, Goals, and Transit Planning Principles ................................................................2-1 Vision for Transit in Minot ..................................................................................................................... 2-1 Elements of the Complete Transit System .................................................................................... 2-3 Service Allocation and Design Principles .......................................................................................... 2-7 Service Allocation Goals................................................................................................................. 2-7 Service Design Guidelines .............................................................................................................. 2-9 3 Short-Term Service Plan ...................................................................................................3-1 Route Descriptions ................................................................................................................................. -

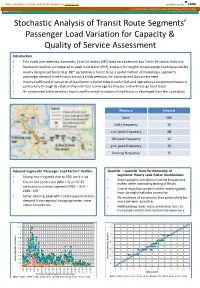

Stochastic Analysis of Transit Route Segments' Passenger Load

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queensland University of Technology ePrints Archive Stochastic Analysis of Transit Route Segments’ Passenger Load Variation for Capacity & Quality of Service Assessment Introduction • This study uses weekday Automatic Fare Collection (AFC) data on a premium bus line in Brisbane, Australia • Stochastic analysis is compared to peak hour factor (PHF) analysis for insight into passenger loading variability • Hourly design load factor (e.g. 88th percentile) is found to be a useful method of modeling a segment’s passenger demand time-history across a study weekday, for capacity and QoS assessment • Hourly coefficient of variation of load factor is found to be a useful QoS and operational assessment measure, particularly through its relationship with hourly average load factor, and with design load factor • An assessment table based on hourly coefficient of variation of load factor is developed from the case study Measure Inbound Span 18h Early frequency 15 a.m. peak frequency 10 Off-peak frequency 15 p.m. peak frequency 15 Evening frequency 15 Inbound Segments’ Passenger Load Factors’ Profiles Quantile – Quantile Tests for Normality of Segments’ Hourly Load Factor Distributions • Strong morning peak due to CBD work trips • Small sample sizes due to limited frequencies • Crush load conditions (MSL > 1) on 07:25 makes other normality testing difficult service across inner segments MSD – SCH – • Line of equality comparison for morning peak COM - INT hour -

MADISON BUS SIZE STUDY Draft Final Report

MADISON BUS SIZE STUDY Draft Final Report January 2014 IN ASSOCIATION WITH: EDWARDS ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS, LLC BAY RIDGE CONSULTING MADISON BUS SIZE STUDY | DRAFT FINAL REPORT City of Madison/Metro Transit Table of Contents Page 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. Purpose of Study .......................................................................................................................................................1-1 Bus Fleet Make-up Considerations and Options ................................................................................................1-1 Unique Characteristics of Madison ........................................................................................................................1-4 How the Study Was Conducted .............................................................................................................................1-6 2 Project overview........................................................................................................................... 2-1 3 Bus Loading Analysis ................................................................................................................... 3-1 Data Collection and Analysis ..................................................................................................................................3-1 Preliminary Results ....................................................................................................................................................3-9 -

General Atomics Low Speed Maglev Technology Development Program (Supplemental #3)

FTA-CA-26-7025.2005 General Atomics Low Speed Maglev Technology Development Program (Supplemental #3) U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Transit May 2005 Administration Final Report OFFICE OF RESEARCH, DEMONSTRATION, AND INNOVATION NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. The United States Government does not endorse products of manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Low Speed Maglev Technology Development Program Final Report May 2005 Prepared by: General Atomics 3550 General Atomics Court San Diego, CA 92121 Prepared for: Federal Transit Administration 400 7th Street, SW Washington, DC 20590 Report Number: FTA-CA-26-7025.2005 GA-A24920 This page intentionally left blank REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED Mat 2005 Final Report Sept 2003 – Dec 2004 4. -

General Guidelines for the Design of Light Rail Transit Facilities in Edmonton

General Guidelines for the Design of Light Rail Transit Facilities in Edmonton Robert R. Clark Retired ETS Supervisor of Special Projects 1984 2 General Guidelines for the Design of Light Rail Transit Facilities in Edmonton This report originally published in 1984 Author: Robert R. Clark, Retired ETS Supervisor of Special Projects Reformatting of this work completed in 2009 OCR and some images reproduced by Ashton Wong Scans completed by G. W. Wong In memory of my mentors: D.L.Macdonald, L.A.(Llew)Lawrence, R.A.(Herb)Mattews, Dudley B. Menzies, and Gerry Wright who made Edmonton Transit a leader in L.R.T. Table of Contents 3 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 6 2.0 The Role Of Light Rail Transit In Edmonton's Transportation System ................................................. 6 2.1 Definition and Description of L.R.T. .................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Integrating L.R.T. into the Transportation System .............................................................................. 7 2.3 Segregation of Guideway .................................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Intrusion and Accessibility ................................................................................................................ 10 2.5 Segregation from Users (Safety) ...................................................................................................... -

Dot 50837 DS1.Pdf

C Investigation of the Relationship between U.S. Department of Transportation Crashworthiness Performance and Weight for Federal Railroad High-Speed Train Operations in the U.S. Administration Office of Research, Development and Technology Washington, DC 20590 \ I ' ~ 'L ~ <;, ... -'< ,~ ,~ .... ··"'-· .,. -4 . .,..,. • ' ' -e. · ~ •4 . ... :~ ( ~ ii DOT/FRA/ORD-20/36 Final Report August 2020 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the United States Government, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States Government. The United States Government assumes no liability for the content or use of the material contained in this document. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. -

Rail Transit Capacity

7UDQVLW&DSDFLW\DQG4XDOLW\RI6HUYLFH0DQXDO PART 3 RAIL TRANSIT CAPACITY CONTENTS 1. RAIL CAPACITY BASICS ..................................................................................... 3-1 Introduction................................................................................................................. 3-1 Grouping ..................................................................................................................... 3-1 The Basics................................................................................................................... 3-2 Design versus Achievable Capacity ............................................................................ 3-3 Service Headway..................................................................................................... 3-4 Line Capacity .......................................................................................................... 3-5 Train Control Throughput....................................................................................... 3-5 Commuter Rail Throughput .................................................................................... 3-6 Station Dwells ......................................................................................................... 3-6 Train/Car Capacity...................................................................................................... 3-7 Introduction............................................................................................................. 3-7 Car Capacity...........................................................................................................