Incorporating TGFU Into a Bachelor of Physical and Health Education Degree at an Australian University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Results Annual

2004 Results Annual BURGER KING TALL BLACKS Australia In New Zealand (Jeep International Series) Players Ed Book (Nelson Giants), Craig Bradshaw (Winthrop University), Dillon Boucher (Auckland Stars), Pero Cameron (Waikato Titans), Mark Dickel (Fenerbache), Paul Henare (Hawks), Mike Homik (Auckland Stars), Phill Jones (Nelson Giants), Troy McLean (Saints), Aaron Olson (Auckland Stars), Brendon Polyblank (Saints), Tony Rampton (Cairns Taipans), Christopher Reay (Southern Methodist University), Lindsay Tait (Auckland Stars), Paora Winitana (Hawks) Coach: Tab Baldwin Assistant Coach: Nenad Vucinic Video Coach: Murray McMahon Managers: Tony Henderson Physiotherapist: Dave Harris Results Lost to Australia 60-90 at Hamilton (Pero Cameron 15, Phill Jones 10) Beat Australia 80-75 at Christchurch (Phill Jones 18, Ed Book 17, Pero Cameron 10) Lost to Australia 79-90 at Invercargill (Pero Cameron 19, Phill Jones 19, Craig Bradshaw 11, Mark Dickel 10) Tour of US & Europe Players Ed Book (Nelson Giants), Craig Bradshaw (Winthrop University), Dillon Boucher (Auckland Stars), Pero Cameron (Waikato Titans), Mark Dickel (Fenerbache), Paul Henare (Hawks), Phill Jones (Nelson Giants), Sean Marks (San Antonio Spurs), Aaron Olson (Auckland Stars), Kirk Penney (Auna Gran Canaria), Brendon Polyblank (Saints), Tony Rampton (Cairns Taipans), Christopher Reay (Southern Methodist University), Paora Winitana (Hawks) Coach: Tab Baldwin Assistant Coach: Nenad Vucinic Video Coach: Murray McMahon Managers: Tony Henderson Physiotherapist: Dave Harris Results Beat Puerto -

Athletics Australia Almanac

HANDBOOK OF RECORDS & RESULTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to the following for their support and contribution to Athletics Australia and the production of this publication. Rankings Paul Jenes (Athletics Australia Statistician) Records Ronda Jenkins (Athletics Australia Records Officer) Results Peter Hamilton (Athletics Australia Track & Field Commission) Paul Jenes, David Tarbotton Official photographers of Athletics Australia Getty Images Cover Image Scott Martin, VIC Athletics Australia Suite 22, Fawkner Towers 431 St Kilda Road Melbourne Victoria 3004 Australia Telephone 61 3 9820 3511 Facsimile 61 3 9820 3544 Email [email protected] athletics.com.au ABN 35 857 196 080 athletics.com.au Athletics Australia CONTENTS 2006 Handbook of Records & Results CONTENTS Page Page Messages – Athletics Australia 8 Australian Road & Cross Country Championships 56 – Australian Sports Commission 10 Mountain Running 57 50km and 100km 57 Athletics Australia Life Members & Merit Awards 11 Marathon and Half Marathon 58 Honorary Life Members 12 Road Walking 59 Recipients of the Merit Award of Athletics Australia 13 Cross Country 61 All Schools Cross Country 63 2006 Results Australian All Schools & Youth Athletics Championships 68 Telstra Selection Trials & 84th Australian Athletics Championships 15 Women 69 Women 16 Men 80 Men 20 Schools Knockout National Final 91 Australian Interstate Youth (Under 18) Match 25 Cup Competition 92 Women 26 Plate Competition 96 Men 27 Telstra A-Series Meets (including 2007 10,000m Championships at Zatopek) 102 -

Hi from the Front Desk! in This Issue

Issue 32 – September 2010 Hi from the front desk! In this issue Congratulations to the Tall Blacks for finishing 12th at the 2010 NZ AA Secondary Schools 2010 FIBA World Basketball Championship for Men. Championships Results Making it through pool play in to the eight finals round to finish 12 th is an outstanding result and it reflects the 2010 NZ A Secondary Schools commitment, passion, energy and skill the team showed Championships Results through out the event. We could not be prouder of our 2010 NZ Open & Wheelchair National team. We also congratulate management and team Championships Results coaching staff for their outstanding contribution to the Tall Blacks. We also thank the fans that showed their support to U18 FIBA Oceania Series the Tall Blacks during their World Championship campaign. NZ Masters Games Competing at the World Championship has opened up New Zealander of the Year Awards opportunities for Tall Blacks Kirk Penney and Thomas Abercrombie. Tom has received interest from European BP Vouchers for Volunteers clubs to land a contract in the next European season and WBC for 2011 Kirk is in the training squad for NBA team San Antonio Spurs. Kirk is currently training in the team and will find out 2010 FIBA Rulebook available online later this month if he makes the final roster. We wish Tom New FIBA President to visit New Caledonia and Kirk the very best. 2010 NZ Breakers Schedule We also are saying thank you and good bye to veteran Tall Blacks Pero Cameron and Phil Jones who played their last game of international basketball for New Zealand at the Despite the devastating earthquake and aftershocks that World Championship. -

Encyclopedia of Australian Football Clubs

Full Points Footy ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CLUBS Volume One by John Devaney Published in Great Britain by Full Points Publications © John Devaney and Full Points Publications 2008 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Every effort has been made to ensure that this book is free from error or omissions. However, the Publisher and Author, or their respective employees or agents, shall not accept responsibility for injury, loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this book whether or not such injury, loss or damage is in any way due to any negligent act or omission, breach of duty or default on the part of the Publisher, Author or their respective employees or agents. Cataloguing-in-Publication data: The Full Points Footy Encyclopedia Of Australian Football Clubs Volume One ISBN 978-0-9556897-0-3 1. Australian football—Encyclopedias. 2. Australian football—Clubs. 3. Sports—Australian football—History. I. Devaney, John. Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net Introduction For most football devotees, clubs are the lenses through which they view the game, colouring and shaping their perception of it more than all other factors combined. To use another overblown metaphor, clubs are also the essential fabric out of which the rich, variegated tapestry of the game’s history has been woven. -

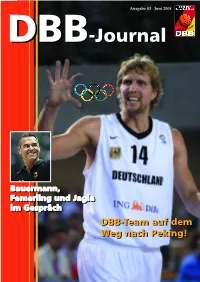

DBB-Journal DBB-Journal

Ausgabe 03 Juni 2008 DBBDBB-Journal-Journal BBaauueerrmmaannnn,, FFeemmeerrlliinngg uunndd JJaaggllaa iimm GGeesspprrääcchh DBB-TeamDBB-Team aufauf demdem WegWeg nachnach Peking!Peking! DBB-Journal 03/08 Liebe Leserinen und Leser, ich begrüße Sie zur 3. Ausgabe des DBB-Journals. Wir freuen uns, Sie heute mit einer geball- mit Perspektive“, das NBBL TOP4, die Diese Worte möchten wir Ihnen nicht vor- ten Ladung an Inhalten erfreuen zu dür- Trainer- und Schiedsrichterseiten (Neue enthalten: fen. Möglich machen es die anstehenden Regeln!!!) oder unsere Rubriken. Wir hof- Es gibt Wege im Basketball, die geht jeder. Es Herren-Länderspiele in Deutschland und fen sehr, dass Ihnen die Mischung gefällt. gib Umwege, die sind nur für Auserwählte. die anschließende Olympia-Qualifikation So ein ein Umweg ist der vdbt mit Gerhard der „Bauermänner“ in Athen. Aus diesem Eine Notiz noch am Rande: besonders Schmidt. Denn über diesen erhielt ich jetzt die Grund halten Sie nicht nur die 3. Ausgabe gefreut hat uns eine Zuschrift des ehema- Nr. 02 des DBB-Journals. Vielen Dank an des DBB-Journals, sondern gleichzeitig ligen Bundestrainers Prof. Günter Hage- beide Wege, und zugleich herzlichen Glück- auch das Hallenheft für die Spiele in Hal- dorn, der sich aus seinem „Exil“ in Korfu wunsch zu diesem faszinierenden Organ. le/Westfalen, Berlin, Bamberg, Hamburg mit gewohnt dichterischen Worten für die Nun, wer in die Sonne (aus)wanderte, wie und Mannheim in der Hand. Zusendung des DBB-Journals bedankte. ich, und andere im Regen (stehen) ließ, darf sich über Umwege nicht wundern. Denn der Natürlich räumen wir den deutschen Regen wäscht Erinnerungen ab! Herren vor diesem wichtigen, Olympi- Herzliche Grüße an alle Heutigen, Jetzigen schen Sommer den größten Platz ein. -

The Maryland Offense

20_001.qxd 31-05-2006 13:16 Pagina 1 MAY / JUNE 2006 20 FOR BASKETBALL EVERYWHERE ENTHUSIASTS FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE ASSIST Zoran Kovacic WOMEN’S U19 SERBIA AND BRENDA FRESE MONTENEGRO OFFENSE Aldo corno and mario buccoliero 1-3-1 zone trap Nancy Ethier THE MARYLAND THE IMPORTANCE OF MENTORSHIP ESTHER WENDER FIBa EUROPE’S YEAR OF WOMEN’s basketball OFFENSE Donna O’Connor THE “OPALS” STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING ;4 20_003.qxd 31-05-2006 12:03 Pagina 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2006 FIBA CALENDAR COACHES MAY FUNDAMENTALS AND YOUTH BASKETBALL 19 - 23.05 FIBA Women’s World Women’s U19 Serbia and Montenegro Offense 4 League, PR Group A, in by Zoran Kovacic Shaoxing, P.R. of China 31.05 - 08.06 FIBA Asia Champions Shooting Drills 8 Cup for Men in Kuwait by Francis Denis June OFFENSE 28.06 - 02.07 FIBA Women’s World 11 League, PR Group B, The High-Post and the Triangle Offenses in Pecs, Hungary by Geno Auriemma 28.06 - 02.07 FIBA Americas U18 The Maryland Offense 16 FIBA ASSIST MAGAZINE Championship for Men by Brenda Frese IS A PUBLICATION OF FIBA in San Antonio, USA International Basketball Federation 51 – 53, Avenue Louis Casaï CH-1216 Cointrin/Geneva Switzerland 28.06 - 02.07 FIBA Americas U18 The Rational Game 20 Tel. +41-22-545.0000, Fax +41-22-545.0099 Championship for by Tamas Sterbenz www.fiba.com / e-mail: [email protected] Women in Colorado IN COLLABORATION WITH Giganti-BT&M, Cantelli Springs, USA Editore, Italy deFENSE PARTNER WABC (World Association of 1-3-1 Zone Trap 23 Basketball Coaches), Dusan Ivkovic President July 04 - 14.07 Wheelchair World by Aldo Corno e Mario Buccoliero Championship for Men, Editor-in-Chief in Amsterdam, HOOP MARKET Giorgio Gandolfi Netherlands Women's Basketball 30 18 - 27.07 FIBA Europe U18 by Raffaele Imbrogno Editorial Office: Cantelli Editore, Championship for Men V. -

Media Mentions 10/14/2010 October 20, 2010

Media Mentions 10/14/2010 October 20, 2010 Media Mentions 10/14/2010 Project # of Articles Print Online Soc. Media B'cast Newswires 2010 Hits 29 5 22 1 1 0 Project: 2010 Hits Type Date Headline City State Prominence Tone Publication / Journalist 10/14/2010 Burt Collects WAC Cross Country Athlete of the Week Award Cache Valley Daily n/a n/a 1 10/14/2010 Never Forgotten Pratt Tribune Pratt KS 2 10/14/2010 Utah football: Former walk-on now a defensive leader Salt Lake Tribune Salt Lake City UT 1 10/14/2010 Spotlight on Schools ? School staff featured Montpelier News-Examiner n/a n/a 1 10/14/2010 Friend's suicide helps import turn life around Stuff.co.nz International n/a 1 10/14/2010 Game on: how the teams line up this season Townsville Bulletin n/a n/a 2 10/14/2010 Hard slog ahead of Sixers' revival Advertiser (Australia) Australia n/a 1 BOTI NAGY 10/14/2010 Utah college enrollments up 5 percent Deseret Morning News Salt Lake City UT 3 Paul Koepp, Deseret News 10/14/2010 USU sets new enrollment record Cache Valley Daily n/a n/a 3 10/14/2010 New rural tax education website Central Utah Daily Herald Provo UT 1 10/14/2010 Help To Track Tax Changes CattleNetwork.com n/a n/a 1 10/14/2010 Enrollment up at crowded Utah colleges KSL-TV Salt Lake City UT 3 10/14/2010 Post a Comment St. George Spectrum n/a n/a 2 10/14/2010 DSC is tops in enrollment growth St. -

R S Iherif 1 ® Gun: Ticer Iiie

------ - ------- 7r'7Trjn‘‘:r„t!. fc r.v.r^ W-;< rf\K 'K'rjr.-'.-r^Wiry!r: y .r“rrr:rv y 7 -.rry -vV >•< r---. > v .\ , ‘'.It- - , •. 5‘'.'x ".''i- 'S'.' ''.'' ■ ' ' ^ | . : :'i ; ' opnE ------ - . - . r : - :« a |M y . '■'■V .;.; ■ :.. ^ . S '" ■’• /"■,.■• ^ .....r 7 | □SVd H i ^ tZOhhL XJ. ’ --------------------- - n r ^ g a w yy7v_31l22S— ^ .H I ■•. ' "3MHMbVd WIC ■ ZU5 - ' ■ I- I002/9T/2X 2?^ I [m p p l l E a HH j i p i ■ Fridi iay, January 5,2001i : • . 505' cents, ^ . W eatoeI ^ l-Tfcra#m*n-^-T------ y: Partly S - 'Iherif - dia M ilytodaywd •—--— 1 ® Ticer W «dtmday ----- " ip tg gg ^ h i g h ^ , . "■ ^ ' _ _ z _ _ niibtlmkte.'nt thbhouM rT------- f ' P « e A 2 + i n Lwlthlathr. wl tEc o n town — ~ - - I v S g i c V a l l gun:iiie - }PMUtfMM0X J BmHs. iP i^lp Detaiails remain sketchyihyon.deathsbfddeputies, Edeniman r ^ B H | ByMarftHI:Hehi ^ "I Ttaa»Wwniw» Witter - _________I ^^mra^Comity Sh^ ~ I - -Jim-Weavjavier and other o ffid als— 3 Thursdaylay released'almost no ; details ab(about a Wednesday night -shottingIg which left two of ^ ’s d u t i e s and a subject ?. ■'• ;J«mRir‘M (m ^:i^ e s n b w Se^oa is cS to a disatisappoint- On dieeverE \ e;dft^ during a ^ start, ini il» momountains ’ . pews confcnference TTiursday morn- . lihat refin Idaho% resreservoirs. mg, Weaveaver said corporals James P « « B 1 n, 30, and Phillip m, 23, were killed in the fe ■ giujHght..Jt._A_$U5pect,_George— 1| — 4 4 0 NEY-—“ llm o ^ -W'.Williams, 47. -

Sports Funding: Federal Balancing Act

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services BACKGROUND NOTE 27 June 2013 Sports funding: federal balancing act Dr Rhonda Jolly Social Policy Section Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Part 1: Federal Government involvement in sport .................................................................................. 3 From Federation to the Howard Government.................................................................................... 3 Federation to Whitlam .................................................................................................................. 3 Whitlam: laying the foundations of a new sports system ............................................................. 4 Fraser: dealing with the Montreal ‘crisis’ ...................................................................................... 5 Figure 1: comment on Australia’s sports system in light of its unspectacular performance in Montreal ............................................................................................................ 6 Table 1: summary of sports funding: Whitlam and Fraser Governments ..................................... 8 Hawke and Keating: a sports commission, the America’s Cup and beginning a balancing act ................................................................................................................................................ 8 Basis of policy .......................................................................................................................... -

2010 Sanfl Annual Report

2010 SANFL ANNUAL REPORT L NF SA B LU C L L A B T O O F E D I A L E D C A T R O P M S AGPIE 1 CONTENTS 2010: A Year In Review 4 McCallum Tomkins Medal 61 Macca’s Cup MVP 62 Corporate Governance 9 Stanley H. Lewis Trophy 63 SA Football Hall of Fame 64 Football Operations 12 Football Operations Overview 14 Corporate Operations 66 State League Competition 16 Corporate Operations Overview 69 SANFL Attendance 18 SANFL Marketing 70 Umpiring 21 SANFL Events 72 Around the Clubs 22 Communications and Media 75 Corporate Partners 76 Game Development 24 Game Development Overview 25 Commercial Operations 78 Participation 26 Commerical Operations Overview 80 Participation Programs 28 Stadium 81 Indigenopus Football 30 Crows and Power 82 Inclusive Programs 32 AAMI Stadium Attendance 83 Talent Development 34 Corporate Hospitality 85 Coaching 37 Human Resources & Safety 87 Community Football 38 Financial Report 88 Community Football Overview 39 Facility Grants 41 SANFL Committees 98 Key Partnerships 44 Country Football Championships 46 League Life Members 99 League Results 47 200 Club 100 Awards and Results 48 The Premiers 50 Bereavements 102 Jack Oatey Medal 53 Magarey Medal 54 2010 Fixture 103 Ken Farmer Medal 56 R.O Shearman Medal 57 The SANFL thanks the following photographers for the use of their images Powerade Star Search 58 in this publication: Deb Curtis, Luke Hemer, Stephen Laffer, Ben Hopkins, Reserves & Macca’s Cup Grand Finals 59 2 Reserves Magarey Medal 60 Roy Vandervegt, Laura Wright, Peter Argent and Tom Miletic. -

Conference Program W Abstracts 15 3 11.Pdf

Active 2 Intended audience codes: 90 mins Cracking the ACHPER Conference Code PRE = Preschool Workshop EY = Early Years 2. Shaping and Focusing ‐ the 1. The columns list the type and title for the session. PY = Primary Years keys for designing and 2. Each session is coded (ie. 2.) and relates to the conference booklet containing MY=Middle Years facilitating student learning. an abstract and further details about the session. SY= Senior Years WINE TOUR 17th April (PRE,EY,PY,TY,C,IN) 3. An indication of the intended audience is provided using “Intended Audience TY= Tertiary Years Wendy Piltz, Uni SA Codes” (see the key to the right). R= Researchers SUNDAY 10am – 4pm 4. Presenters name and organisation. IN=Instructors C = Coaches Sunday 17th Social Activity ‐ Barossa Valley Wine Tour 10am – 4pm (Additional cost – approx. $60) Sunday 17th Registration Evening 4pm ‐ 6pm “Tasting South Australia” MONDAY 18th April 8am ‐ 8.50am Registration 9.00 – 10.30am Opening and Keynote ‐ Jean Blaydes‐Madigan (USA) ‐ Action Based Learning: How Brain Research Links Movement and Learning. Jean Blaydes Madigan is an Elementary School Physical Educator with 30 years teaching experience, recognized for her excellence in teaching. She was awarded Elementary Physical Education Teacher of the year for Texas in 1992 and in 1993 for the National Association for Sport and Physical Education (Southern Districts). In 1997 she received the Texas Association of Health Physical Education Recreation and Dance (TAHPERD) Honor Award. Jean will present contemporary information linking brain based learning theory with movement and how this can be applied to teaching practice to promote quality learning. -

2014 Sanfl Annual Report

2014 SANFL ANNUAL REPORT MUNIT OM Y C L NF SA B LU C L L A B T F L O O L O OTBA F E D I A L E D C A T R O P M S AGPIE 1 Glenelg’s Ty Allen runs through the banner for his 100th match. (Paul Melrose, SA Football Budget) A primary school student goes through her football paces 2014: A YEAR IN atREVIEW a Port Adelaide development zone training session. FINANCIAL AAMI STADIUM In November 2014, the SA Football Commission formally The historic opening of the redeveloped Adelaide Oval in March PERFORMANCE The SANFL recorded an increase in cash reserves of signed a contract with developer Commercial & General $1.34 million following the first full year of operations at for the sale and 20+ year redevelopment of the AAMI Stadium precinct. 2014 will be remembered as a watershed year Later in the year, the parties would be back at the Adelaide Oval. in the history of South Australian football – negotiating table again for the planned review of the As part of the agreement, the SANFL received an up- and the SANFL itself. Adelaide Oval commercial model. This was a detailed The SANFL achieved a positive net cash flow from front payment of $10 million which was transferred to process that would set the parameters for the next three operating activities of $1m compared to $0.3m in 2013 the AFL to retire debt, money borrowed as part of the The Adelaide Oval will, naturally, take the headlines when seasons and was not concluded until early March.