Low-Profile Elastic Exosuit Reduces Back Muscle Fatigue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Structure and Function of Breathing

CHAPTERCONTENTS The structure-function continuum 1 Multiple Influences: biomechanical, biochemical and psychological 1 The structure and Homeostasis and heterostasis 2 OBJECTIVE AND METHODS 4 function of breathing NORMAL BREATHING 5 Respiratory benefits 5 Leon Chaitow The upper airway 5 Dinah Bradley Thenose 5 The oropharynx 13 The larynx 13 Pathological states affecting the airways 13 Normal posture and other structural THE STRUCTURE-FUNCTION considerations 14 Further structural considerations 15 CONTINUUM Kapandji's model 16 Nowhere in the body is the axiom of structure Structural features of breathing 16 governing function more apparent than in its Lung volumes and capacities 19 relation to respiration. This is also a region in Fascla and resplrstory function 20 which prolonged modifications of function - Thoracic spine and ribs 21 Discs 22 such as the inappropriate breathing pattern dis- Structural features of the ribs 22 played during hyperventilation - inevitably intercostal musculature 23 induce structural changes, for example involving Structural features of the sternum 23 Posterior thorax 23 accessory breathing muscles as well as the tho- Palpation landmarks 23 racic articulations. Ultimately, the self-perpetuat- NEURAL REGULATION OF BREATHING 24 ing cycle of functional change creating structural Chemical control of breathing 25 modification leading to reinforced dysfunctional Voluntary control of breathing 25 tendencies can become complete, from The autonomic nervous system 26 whichever direction dysfunction arrives, for Sympathetic division 27 Parasympathetic division 27 example: structural adaptations can prevent NANC system 28 normal breathing function, and abnormal breath- THE MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION 30 ing function ensures continued structural adap- Additional soft tissue influences and tational stresses leading to decompensation. -

Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Anatomy

ThoracicThoracic andand LumbarLumbar SpineSpine AnatomyAnatomy www.fisiokinesiterapia.biz ThoracicThoracic VertebraeVertebrae Bodies Pedicles Laminae Spinous Processes Transverse Processes Inferior & Superior Facets Distinguishing Feature – Costal Fovea T1 T2-T8 T9-12 ThoracicThoracic VertebraeVertebrae andand RibRib JunctionJunction FunctionsFunctions ofof ThoracicThoracic SpineSpine – Costovertebral Joint – Costotransverse Joint MotionsMotions – All available – Flexion and extension limited – T7-T12 LumbarLumbar SpineSpine BodiesBodies PediclesPedicles LaminaeLaminae TransverseTransverse ProcessProcess SpinousSpinous ProcessProcess ArticularArticular FacetsFacets LumbarLumbar SpineSpine ThoracolumbarThoracolumbar FasciaFascia LumbarLumbar SpineSpine IliolumbarIliolumbar LigamentsLigaments FunctionsFunctions ofof LumbarLumbar SpineSpine – Resistance of anterior translation – Resisting Rotation – Weight Support – Motion IntervertebralIntervertebral DisksDisks RatioRatio betweenbetween diskdisk thicknessthickness andand vertebralvertebral bodybody heightheight DiskDisk CompositionComposition – Nucleus pulposis – Annulus Fibrosis SpinalSpinal LigamentsLigaments AnteriorAnterior LongitudinalLongitudinal PosteriorPosterior LongitudinalLongitudinal LigamentumLigamentum FlavumFlavum InterspinousInterspinous LigamentsLigaments SupraspinousSupraspinous LigamentsLigaments IntertransverseIntertransverse LigamentsLigaments SpinalSpinal CurvesCurves PosteriorPosterior ViewView SagittalSagittal ViewView – Primary – Secondary -

Familial Absenceof the Pectoralis Major, Serratus Anterior, And

J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.22.5.390 on 1 October 1985. Downloaded from Journal of Medical Genetics, 1985, 22, 390-392 Familial absence of the pectoralis major, serratus anterior, and latissimus dorsi muscles T J DAVID* AND R M WINTERt From *the Department of Child Health, University ofManchester; and tthe Kennedy-Galton Centrefor Clinical Genetics, Harperbury Hospital, Hertfordshire. SUMMARY Congenital absence of shoulder girdle muscles is described in three generations of a family. The proband, a 3 year old boy, had absence of the sternocostal head of the right pectoralis major. His father had absence of the left serratus anterior and part of the left latissimus dorsi and his paternal grandfather had absence of the lower two-thirds of the left pectoralis major, with absence of the left serratus anterior and latissimus dorsi muscles. The condition is probably the result of a dominant gene. These observations show that absence of the pectoralis major is part of a wider spectrum of shoulder girdle defects. Where genetic advice is sought by persons with apparently sporadic absence of the pectoralis major, examination of the relatives is necessary. The Poland anomaly comprises unilateral absence of of the Poland anomaly or isolated absence of the the pectoralis major combined with an ipsilateral pectoralis. The pedigree is shown in fig 1. malformation of the hand which usually includes syndactyly. It is currently unclear whether isolated Case reports absence of the pectoralis major muscle and the CASE 1 Poland anomaly are part of the same spectrum of IV.3 was a male infant, the product of the first defects or are separate entities.1 Both are consis- 30 year old http://jmg.bmj.com/ tently unilateral and both are usually sporadic pregnancy of a 29 year old mother and 2 father, who had been married for seven years. -

Effect of Latissimus Dorsi Muscle Strengthening in Mechanical Low Back Pain

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2019): 7.583 Effect of Latissimus Dorsi Muscle Strengthening in Mechanical Low Back Pain 1 2 Vishakha Vishwakarma , Dr. P. R. Suresh 1, 2PCPS & RC, People’s University, Bhopal (M.P.), India Abstract: Mechanical low back pain (MLBP) is one of the most common musculoskeletal pain syndromes, affecting up to 80% of people at some point during their lifetime. Sources of back pain are numerous, usually sought in as lesion of disc or facet joints at L4- L5 and L5-S1 levels. Studies have shown that 40% of all back pain is of thoracolumbar origin. The term meachnical low back pain also gives reassurance that there is no damage to the nerves or spinal pathology. The clinical presentation of mechanical low back pain usually the ages 18-55 years is in the lumbo sacral region. A study was conducted to evaluate the designed to check the effectiveness of Conventional Exercises alone in Mechanical low back pain and along with the latissimus dorsi muscle strengthening, data was collected from People’s hospital, Bhopal (age group-30-45 yr both male and female randomly) Keywords: Visual analog scale, Assessment chart, Treatment table, Data collection sheets, Essential stationery materials, Computer, SPSS Software etc. 1. Introduction Back pain is a primary to seek medical advice considering 80% of people suffering from back pain. Mechanical low back pain is defined as a result of minor intervertebral dysfunction and referred pain in the low back The latissimus dorsi is a large, flat muscle on the back that and hip region, and can often be confused with the other stretches to the sides, behind the arm, and is partly covered pathologies that may cause these symptoms.18 by the trapezius on the back near the midline, the word latissimus dorsi comes from Latin and its means, broadest muscle of the back dorsum means back. -

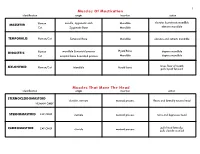

Muscles of Mastication Muscles That Move the Head

1 Muscles Of Mastication identification origin insertion action maxilla, zygomatic arch Mandible elevates & protracts mandible MASSETER Human Cat Zygomatic Bone Mandible elevates mandible TEMPORALIS Human/Cat Temporal Bone Mandible elevates and retracts mandible Hyoid Bone DIGASTRIC Human mandible & mastoid process depress mandible Cat occipital bone & mastoid process Mandible depress mandible raises floor of mouth; MYLOHYOID Human/Cat Mandible Hyoid bone pulls hyoid forward Muscles That Move The Head identification origin insertion action STERNOCLEIDOMAStoID clavicle, sternum mastoid process flexes and laterally rotates head HUMAN ONLY STERNOMAStoID CAT ONLY sternum mastoid process turns and depresses head pulls head laterally; CLEIDOMAStoID CAT ONLY clavicle mastoid process pulls clavicle craniad 2 Muscles Of The Hyoid, Larynx And Tongue identification origin insertion action Human Sternum Hyoid depresses hyoid bone STERNOHYOID Cat costal cartilage 1st rib Hyoid pulls hyoid caudally; raises ribs and sternum sternum Throid cartilage of larynx Human depresses thyroid cartilage STERNothYROID Cat costal cartilage 1st rib Throid cartilage of larynx pulls larynx caudad elevates thyroid cartilage and Human thyroid cartilage of larynx Hyoid THYROHYOID depresses hyoid bone Cat thyroid cartilage of larynx Hyoid raises larynx GENIOHYOID Human/Cat Mandible Hyoid pulls hyoid craniad 3 Muscles That Attach Pectoral Appendages To Vertebral Column identification origin insertion action Human Occipital bone; Thoracic and Cervical raises clavicle; adducts, -

Study of Axillary Arch: Embryological Basis and Its Clinical Implications

Original Article Indian Journal of Anatomy291 Volume 7 Number 3, May - June 2018 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21088/ija.2320.0022.7318.12 Study of Axillary Arch: Embryological Basis and Its Clinical Implications Divya Shanthi D’Sa1, Vasudha T.K.2 Abstract Aim: To study the incidence, embryological basis and clinical implications of unusual but most common anatomical variant, axillary arch. Materials & Methods: The study was conducted in the department of Anatomy, Subbaiah Institute of Medical Sciences, Shimoga during routine cadaveric dissection on 60 upper limbs. Results: Of the 60 upper limbs dissected, Axillary arch was seen in one right upper limb. It was extending between latissimus dorsi and fascia covering the subscapularis muscle after crossing the posterior cord of brachial plexus and circumflex scapular vessels. It was supplied by a branch from the thoracodorsal nerve. Conclusion: The presence of an axillary arch needs to be considered in differential diagnosis of axillary swellings and also in surgeries of shoulder region. Therefore it is mandatory to know the variant slips of the musculotendinous arch. Keywords: Axillary Arch; Latissimus Dorsi; Neurovascular Bundle; Clinical Implications. Introduction other variants of this anomaly have also been observed like the muscle adhering to the coracoid process of the scapula, medial epicondyle of the Humerus or The axillary arch muscle is an accessory muscle blending with the fibers of teres major, long head of that extends between the pectoralis major and triceps brachii, coracobrachialis -

The Erector Spinae Group Is a Group of 3 Sets of Muscles—Spinalis, Longissimus, and Iliocostalis

The Erector Spinae Group is a group of 3 sets of muscles—spinalis, longissimus, and iliocostalis. The spinalis group are located off of the spinous processes of the vertebrae. The longissimus group are located off of the transverse processes of the vertebrae and the iliocostalis group are located off of the ribs. By knowing these regions we can see that the spinalis group is the most medial and the iliocostalis group is most lateral. 1 During full flexion the erector spinae are relaxed. When standing upright the muscles are active and extension is initiated by the hamstrings—so when you lift a load from the bent over position it causes injury to the erector spinae group. Always lift with a straight back, not when you are hunched over. 2 3 The interspinalis muscles are very tiny muscles that connect from one spinous process to another. The intertransversarii muscles connect between each transverse process. The multifidus lies deep to the erector spinae muscles and it connects from one transverse process to the next spinous process. 4 The rotatores differs from the multifidus by going from 1 transverse process to 2 spinous processes. 5 The external obliques are the most superficial of the oblique muscles. Notice the fibers angle downward and medially, which allows for lateral flexion to same side and rotation to the opposite side. What other muscle does that (neck muscle)?? Once again it takes both sides to contract to cause trunk flexion to occur and only 1 side to cause the rotation and lateral flexion. Now the internal obliques have the fibers directed more horizontally which allows for rotation to the same side when 1 side contracts unlike the external obliques. -

The Anatomy and Function of the Equine Thoracolumbar Longissimus Dorsi Muscle

Aus dem Veterinärwissenschaftlichen Department der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Lehrstuhl für Anatomie, Histologie und Embryologie Vorstand: Prof. Dr. Dr. Fred Sinowatz Arbeit angefertigt unter der Leitung von Dr. Renate Weller, PhD, MRCVS The Anatomy and Function of the equine thoracolumbar Longissimus dorsi muscle Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der tiermedizinischen Doktorwürde der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Vorgelegt von Christina Carla Annette von Scheven aus Düsseldorf München 2010 2 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Tierärztlichen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Joachim Braun Berichterstatter: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Johann Maierl Korreferentin: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Bettina Wollanke Tag der Promotion: 24. Juli 2010 3 Für meine Familie 4 Table of Contents I. Introduction................................................................................................................ 8 II. Literature review...................................................................................................... 10 II.1 Macroscopic anatomy ............................................................................................. 10 II.1.1 Comparative evolution of the body axis ............................................................ 10 II.1.2 Axis of the equine body ..................................................................................... 12 II.1.2.1 Vertebral column of the horse.................................................................... -

EMG Analysis of Latissimus Dorsi, Erector Spinae and Middle Trapezius Muscle Activity During Spinal Rotation: a Pilot Study Jamie Flint University of North Dakota

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Physical Therapy Scholarly Projects Department of Physical Therapy 2015 EMG Analysis of Latissimus Dorsi, Erector Spinae and Middle Trapezius Muscle Activity during Spinal Rotation: A Pilot Study Jamie Flint University of North Dakota Toni Linneman University of North Dakota Rachel Pederson University of North Dakota Megan Storstad University of North Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/pt-grad Part of the Physical Therapy Commons Recommended Citation Flint, Jamie; Linneman, Toni; Pederson, Rachel; and Storstad, Megan, "EMG Analysis of Latissimus Dorsi, Erector Spinae and Middle Trapezius Muscle Activity during Spinal Rotation: A Pilot Study" (2015). Physical Therapy Scholarly Projects. 571. https://commons.und.edu/pt-grad/571 This Scholarly Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Physical Therapy at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physical Therapy Scholarly Projects by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ------- ---- ------------------------------- EMG ANALYSIS OF LATISSIMUS DORSI, ERECTOR SPINAE AND MIDDLE TRAPEZIUS MUSCLE ACTIVITY DURING SPINAL ROTATION: A PILOT STUDY by Jamie Flint, SPT Toni Linneman, SPT Rachel Pederson, SPT Megan Storstad, SPT Bachelor of Science in Physical Education, Exercise Science and Wellness University of North Dakota, 2013 A Scholarly Project Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the -

Chapter 7 Body Systems

Deep Muscles of the Back and Posterior Neck 1 Responsible for neck and head extension, lateral flexion, and rotation Affect trunk movements Play a role in maintaining proper spinal curve Complex column extending from sacrum to skull In these areas, massage is most effective when applied with a slow, sustained, broad-based compressive force. 2 Superficial group of back muscles 3 Intermediate group of back muscles – serratus posterior muscles 4 Deep group of back muscles – erector spinae muscles 5 Deep group of back muscles – transversospinales and segmental muscles and suboccipital muscles 6 Deep Posterior Cervical Muscles Splenius capitis and splenius cervicis What is the referred pain pattern of the splenius capitis and splenius cervicis? To the top of the skull, the eye, and the shoulder. 8 Vertical Muscles Erector Spinae Group I Iliocostalis lumborum, iliocostalis thoracis, and iliocostalis cervicis What is the isometric function of the iliocostalis lumborum, iliocostalis thoracis, and iliocostalis cervicis? These muscles stabilize the spine and pelvis. 9 Vertical Muscles Erector Spinae Group II Longissimus thoracis, longissimus cervicis, and longissimus capitis Longissimus means “the longest”; the muscles pictured on the left relate to the thorax, neck, and head, respectively. 10 Spinalis thoracis, spinalis cervicis, and spinalis capitis What are the referred pain patterns of the spinalis thoracis, spinalis cervicis, and spinalis capitis? The scapular, lumbar, abdominal, and gluteal areas. Oblique Muscles Transversospinales Group I Semispinalis thoracis, semispinalis cervicis, and semispinalis capitis 12 Multifidus What does multifidus mean? Many split parts. What is the eccentric function of the semispinalis thoracis, semispinalis cervicis, and semispinalis capitis? These muscles engage in flexion and contralateral lateral flexion of the trunk, neck, and head. -

The Relationship Between the Angle of Curvature of the Spine and SEMG Amplitude of the Erector Spinae in Young School-Children

applied sciences Article The Relationship between the Angle of Curvature of the Spine and SEMG Amplitude of the Erector Spinae in Young School-Children Jacek Wilczy ´nski* , Przemysław Karolak, Sylwia Janecka, Magdalena Kabała and Natalia Habik-Tatarowska Department Posturology, Hearing and Balance Rehabilitation, Institute of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, Al. IX Wieków Kielc 19, 25-317 Kielce, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 11 July 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: The aim of the study was to analyze the relationship between the angle of spinal curvature and surface electromyography (SEMG) amplitude of the erector spinae in young school-children. A total of 251 children aged 7–8 participated in the study. The analysis involved 103 (41%) children with scoliosis, 141 (56.17%) with scoliotic posture, and seven (3.0%) with normal posture. Body posture was evaluated using the Diers formetric III 4D optoelectronic method. Analysis of SEMG amplitude of the erector spinae was performed with the Noraxon TeleMyo DTS apparatus. A significant correlation was found between the angle of spinal curvature and the SEMG amplitude of the erector spinae. The most important and statistically significant predictor of the SEMG amplitude and scoliosis angle in the scoliosis group was the standing position, chest segment, right side. The largest generalized SEMG amplitude of the erector spinae occurred in both boys and girls with scoliosis. Impaired balance of muscle tension in the erector spinae can trigger a set of changes that create a clinical and anatomopathological image of spinal curvature. -

Sonographic Tracking of Trunk Nerves: Essential for Ultrasound-Guided Pain Management and Research

Journal name: Journal of Pain Research Article Designation: Perspectives Year: 2017 Volume: 10 Journal of Pain Research Dovepress Running head verso: Chang et al Running head recto: Sonographic tracking of trunk nerve open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S123828 Open Access Full Text Article PERSPECTIVES Sonographic tracking of trunk nerves: essential for ultrasound-guided pain management and research Ke-Vin Chang1,2 Abstract: Delineation of architecture of peripheral nerves can be successfully achieved by Chih-Peng Lin2,3 high-resolution ultrasound (US), which is essential for US-guided pain management. There Chia-Shiang Lin4,5 are numerous musculoskeletal pain syndromes involving the trunk nerves necessitating US for Wei-Ting Wu1 evaluation and guided interventions. The most common peripheral nerve disorders at the trunk Manoj K Karmakar6 region include thoracic outlet syndrome (brachial plexus), scapular winging (long thoracic nerve), interscapular pain (dorsal scapular nerve), and lumbar facet joint syndrome (medial branches Levent Özçakar7 of spinal nerves). Until now, there is no single article systematically summarizing the anatomy, 1 Department of Physical Medicine sonographic pictures, and video demonstration of scanning techniques regarding trunk nerves. and Rehabilitation, National Taiwan University Hospital, Bei-Hu Branch, In this review, the authors have incorporated serial figures of transducer placement, US images, Taipei, Taiwan; 2National Taiwan and videos for scanning the nerves in the trunk region and hope this paper helps physicians University College of Medicine, familiarize themselves with nerve sonoanatomy and further apply this technique for US-guided Taipei, Taiwan; 3Department of Anesthesiology, National Taiwan pain medicine and research.