'Subaltern' Or the 'Sovereign': Revisiting the History of Tribal State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socio-Economic Status of Scheduled Tribes in Jharkhand Indian Journal

Indian Journal of Spatial Sc ience Vol - 3.0 No. 2 Winter Issue 2012 pp 26 - 34 Indian Journal of Spatial Science EISSN: 2249 – 4316 ISSN: 2249 – 3921 journal homepage: www.indiansss.org Socio-economic Status of Scheduled Tribes in Jharkhand Dr. Debjani Roy Head: Department of Geography, Nirmala College, Ranchi University, Ranchi ARTICLE INFO A B S T R A C T Article History: “Any tribe or tribal community or part of or group within any tribe or tribal Received on: community as deemed under Article 342 is Scheduled Tribe for the purpose of the 2 May 2012 Indian Constitution”. Like others, tribal society is not quite static, but dynamic; Accepted in revised form on: 9 September 2012 however, the rate of change in tribal societies is rather slow. That is why they have Available online on and from: remained relatively poor and backward compared to others; hence, attempts have 13 October 2012 been made by the Government to develop them since independence. Still, even after so many years of numerous attempts the condition of tribals in Jharkhand Keywords: presents one of deprivation rather than development. The 2011 Human Scheduled Tribe Demographic Profile Development Report argues that the urgent global challenges of sustainability and Productivity equity must be addressed together and identifies policies on the national and Deprivation global level that could spur mutually reinforcing progress towards these Level of Poverty interlinked goals. Bold action is needed on both fronts for the sustained progress in human development for the benefit of future generations as well as for those living today. -

S. No. Case ID Name Age Gender Address Sample Collection Date

Sample S. No. Case ID Name Age Gender Address Result Date Status District Block Collection Date 1 PIL006482 Azmi 32 female 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT H.N.181 Vill-Shahgarh tahsil 2 PIL006617 Balvinder Kaur 58 female 2020-02-04 2020-02-06 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Kalinagar 3 PIL006621 Balvinder Singh 45 male Haidarpur Amariya 2020-03-19 2020-03-21 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 4 PIL006709 Bhairo Nath 60 male 2020-03-29 2020-03-30 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 5 PIL007046 Chandra Pal 21 male 2020-03-30 2020-03-31 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 6 PIL008157 Dr. Mustak Ahmad 38 male 2020-03-25 2020-03-25 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 7 PIL0011730 Mahboob Hasan 33 male 33 Chidiyadah, Neoria 2020-03-07 2020-03-08 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 8 PIL0013307 Mohd. Aafaq 55 male 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 9 PIL0013311 Mohd. Akram 52 male 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 10 PIL0014401 Nitin Kapoor 34 male 2020-03-21 2020-03-22 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 11 PIL0017400 Rubeena 26 female 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 12 PIL0017401 Rubina Parveen 46 female 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 13 PIL0018711 Shabeena Parveen 42 female 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 14 PIL0021387 Usman 71 male 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 15 PIL0088704 Neha D/ indra pal 19 female tarkothi 2020-04-02 2020-04-03 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Puranpur 16 PIL0090571 Mohd.Sahib 15 male 2020-04-04 2020-04-06 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Other 17 PIL0090572 RoshanLal 28 male नो डेटा 2020-04-04 2020-04-06 -

The Pakistan, India, and China Triangle

India frequently experience clashes The Pakistan, along their shared borders, espe- cially on the de facto border of Pa- India, and kistan-administered and India-ad- 3 ministered Kashmir.3 China Triangle Pakistan’s Place in The triangular relationship be- the Sino-Indian tween India, China, and Pakistan is of critical importance to regional Border Dispute and global stability.4 Managing the Dr. Maira Qaddos relationship is an urgent task. Yet, the place of Pakistan in the trian- gular relationship has sometimes gone overlooked. When India and China were embroiled in the recent military standoff at the Line of Ac- tual Control (LAC), Pakistan was mentioned only because of an ex- pectation (or fear) that Islamabad would exploit the situation to press its interests in Kashmir. At that time, the Indian-administered por- tion of Kashmir had been experi- t is quite evident from the history encing lockdowns and curfews for of Pakistan’s relationship with months, raising expectations that I China that Pakistan views Sino- Pakistan might raise the tempera- Indian border disputes through a ture. But although this insight Chinese lens. This is not just be- (that the Sino-Indian clashes cause of Pakistani-Chinese friend- would affect Pakistan’s strategic ship, of course, but also because of interests) was correct, it was in- the rivalry and territorial disputes complete. The focus should not that have marred India-Pakistan have been on Pakistani opportun- relations since their independ- ism, which did not materialize, but ence.1 Just as China and India on the fundamental interconnect- have longstanding disputes that edness that characterizes the led to wars in the past (including, South Asian security situation—of recently, the violent clashes in the which Sino-Indian border disputes Galwan Valley in May-June are just one part. -

The Political Art of Patience: Adivasi Resistance in India

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Political Art of Patience: Adivasi Resistance in India Citation for published version: Johnston, C 2012, 'The Political Art of Patience: Adivasi Resistance in India', Antipode, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 1268-1286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00967.x Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00967.x Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Antipode Publisher Rights Statement: Final published version is available at www.interscience.wiley.com copyright of Wiley-Blackwell (2012) General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 This is the author’s final draft or ‘post-print’ version. Author retains copyright (2012). The final version was published in Antipode copyright of Wiley-Blackwell (2012) and is available online. Cite As: Johnston, C 2012, 'The political art of patience: adivasi -

List of Candidates (Provisionally Eligiblenot Eligible) for Research

Central University of Rajasthan Ph.D. Admissions 2021 List of Candidates (Provisionally Eligible/Not Eligible) for Research Aptitude Test, Presentation and Interview Ph.D. in Atmospheric Sciences Provisionally ID No. Student_Name Eligible Remarks (YES / NO) 116 SUBHASH YADAV YES 1227 ANIRUDH SHARMA YES 1345 ROHITASH YADAV YES 219 RITU BHARGAVA RAI YES Subject to submission of application through proper channel 363 SURINA ROUTRAY YES 396 SHANTANU SINHA YES 404 SHRAVANI BANERJEE YES 915 RAJNI CHOUDHARY YES 956 SONIYA YADAV YES 425 JYOTI PATHAK YES 85 SURUCHI YES 1404 BARKHA KUMAWAT NO No proof of qualifying any National Level Examination 988 ANJANA YADAV NO No proof of National Level Examination NOTE: Grievances, if any, w.r.t. above list may be submitted on [email protected] on or before 11th August 2021. The above list is only to appear for Research Aptitude Test, Presentation and Interview and it does not give any claim of final Admission to Ph.D. programme. Page No. 1 of 31 Central University of Rajasthan Ph.D. Admissions 2021 List of Candidates (Provisionally Eligible/Not Eligible) for Research Aptitude Test, Presentation and Interview Ph.D. in Biochemistry Provisionally ID No. Student_Name Eligible Remarks (YES / NO) 1000 SIMRAN BANSAL YES 1032 RAJNI YES 1047 AKASH CHOUDHARY YES 1048 AKASH CHOUDHARY YES 1050 ADITI SHARMA YES 1065 NAVEEN SONI YES 1168 NIDHI KUMARI YES 1185 ANISHA YES 1206 ABHISHEK RAO YES 1212 RASHMI YES 1228 NEELAM KUMARI YES 1241 ANUKRATI ARYA YES 1319 -

Compounding Injustice: India

INDIA 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) – July 2003 Afsara, a Muslim woman in her forties, clutches a photo of family members killed in the February-March 2002 communal violence in Gujarat. Five of her close family members were murdered, including her daughter. Afsara’s two remaining children survived but suffered serious burn injuries. Afsara filed a complaint with the police but believes that the police released those that she identified, along with many others. Like thousands of others in Gujarat she has little faith in getting justice and has few resources with which to rebuild her life. ©2003 Smita Narula/Human Rights Watch COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: THE GOVERNMENT’S FAILURE TO REDRESS MASSACRES IN GUJARAT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] July 2003 Vol. 15, No. 3 (C) COMPOUNDING INJUSTICE: The Government's Failure to Redress Massacres in Gujarat Table of Contents I. Summary............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Impunity for Attacks Against Muslims............................................................................................................... -

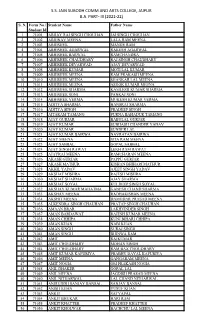

Ss Jain Subodh Comm and Arts College, Jaipur Ba Part

S.S. JAIN SUBODH COMM AND ARTS COLLEGE, JAIPUR B.A. PART- III (2021-22) S. N. Form No./ Student Name Father Name Student Id 1 71001 ABHAY RAJ SINGH CHOUHAN JAI SINGH CHOUHAN 2 71002 ABHINAV MEENA LALA RAM MEENA 3 71003 ABHISHEK MANGE RAM 4 71004 ABHISHEK AGARWAL RAKESH AGARWAL 5 71005 ABHISHEK BARWAL RAMCHANDRA 6 71006 ABHISHEK CHAUDHARY RAJ SINGH CHAUDHARY 7 71007 ABHISHEK DEVARWAD AJAY DEVARWAD 8 71008 ABHISHEK KUMAR MOTI LAL KUMAR 9 71009 ABHISHEK MEENA RAM PRAKASH MEENA 10 71010 ABHISHEK MEENA SHANKAR LAL MEENA 11 71011 ABHISHEK MEENA ASHOK KUMAR MEENA 12 71012 ABHISHEK SHARMA KAMLESH KUMAR SHARMA 13 71013 ABHISHEK SONI PANKAJ SONI 14 71014 ABHISHEK VERMA MUKESH KUMAR VERMA 15 71015 ADITYA SHARMA HANSRAJ SHARMA 16 71016 ADITYA SINGH PRADEEP SINGH 17 71017 AITARAM TAMANG PURNA BAHADUR TAMANG 18 71018 AJAY GURJAR BABULAL GURJAR 19 71019 AJAY KUMAR SUBHASH CHANDER YADAV 20 71020 AJAY KUMAR SUNDER LAL 21 71021 AJAY KUMAR BAIRWA NAVRATAN BAIRWA 22 71022 AJAY MEENA SITA RAM MEENA 23 71023 AJAY SABBAL GOPAL SABBAL 24 71024 AJAY SINGH RAWAT LEKH RAM RAWAT 25 71025 AJAYRAJ MEENA RAMCHARAN MEENA 26 71026 AKASH GURJAR PAPPU GURJAR 27 71027 AKASH MATHUR KISHAN BHIHARI MATHUR 28 71028 AKHIL YADAV AJEET SINGH YADAV 29 71029 AKSHAT MISHRA RAJESH MISHRA 30 71030 AKSHAT SHARMA AJAY SHARMA 31 71031 AKSHAT SOYAL KULDEEP SINGH SOYAL 32 71032 AKSHAY KUMAR MAHATMA GANESH CHAND SHARMA 33 71033 AKSHAY MEENA RADHAKISHAN MEENA 34 71034 AKSHIT MEENA DAMODAR PRASAD MEENA 35 71035 ALKENDRA SINGH CHAUHAN PRATAP SINGH CHAUHAN 36 71036 AMAAN BRAR LAKHVINDER SINGH -

Indian Anthropology

INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN INDIA Dr. Abhik Ghosh Senior Lecturer, Department of Anthropology Panjab University, Chandigarh CONTENTS Introduction: The Growth of Indian Anthropology Arthur Llewellyn Basham Christoph Von-Fuhrer Haimendorf Verrier Elwin Rai Bahadur Sarat Chandra Roy Biraja Shankar Guha Dewan Bahadur L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer Govind Sadashiv Ghurye Nirmal Kumar Bose Dhirendra Nath Majumdar Iravati Karve Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia Dharani P. Sen Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas Shyama Charan Dube Surajit Chandra Sinha Prabodh Kumar Bhowmick K. S. Mathur Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi Triloki Nath Madan Shiv Raj Kumar Chopra Andre Beteille Gopala Sarana Conclusions Suggested Readings SIGNIFICANT KEYWORDS: Ethnology, History of Indian Anthropology, Anthropological History, Colonial Beginnings INTRODUCTION: THE GROWTH OF INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY Manu’s Dharmashastra (2nd-3rd century BC) comprehensively studied Indian society of that period, based more on the morals and norms of social and economic life. Kautilya’s Arthashastra (324-296 BC) was a treatise on politics, statecraft and economics but also described the functioning of Indian society in detail. Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya from 324 BC to 300 BC. He also wrote a book on the structure and customs of Indian society. Al Biruni’s accounts of India are famous. He was a 1 Persian scholar who visited India and wrote a book about it in 1030 AD. Al Biruni wrote of Indian social and cultural life, with sections on religion, sciences, customs and manners of the Hindus. In the 17th century Bernier came from France to India and wrote a book on the life and times of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, their life and times. -

Unit 2 Tribes of Jharkhand, Gujarat and Orissa

UNIT 2 TRIBES OF JHARKHAND, GUJARAT AND ORISSA Structure 2.0 Objectives 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Tribal Habitation: Gujarat 2.3 Mobilization of Tribes in Gujarat 2.4 Jharkhand: Tribal Pattern 2.5 Important Tribes of Jharkhand 2.6 Tribal Development in Jharkhand 2.7 Tribes of Orissa 2.8 Major Tribes of Orissa 2.9 Let Us Sum Up 2.10 Further Readings and References 2.0 OBJECTIVES The unit delineates itself to the following objectives: To understand the concept of tribe and to study the tribal population settled in Jharkhand, Gujarat and Orissa; To study the socio-economic and cultural life of these tribes; To analyze the challenges and opportunities for development of these tribal communities; and To study the efforts of the Governmental agencies and other stakeholders toward mainstreaming the tribes. 2.1 INTRODUCTION The tribal population is identified as the aboriginal inhabitants of our country. They are the most vulnerable section of our society, living in natural and unpopulated surrounding, far away from civilization with their traditional values, customs and beliefs. There has been a long and enduring debate among the social scientists to define a tribe. According to the Constitution “Any tribe or tribal community or part of or group within any tribe or tribal community as deemed under article 342 are Scheduled Tribes for the purpose of the Constitution”. Thus, the groups, which are in the Scheduled list of the President of India, are defined as Scheduled Tribes. There is a procedure for including tribal groups in the Scheduled list. The President may, after consulting with the governor of a State, by public notification, specify the tribes, which would deem to be Scheduled Tribes, in relation to that State. -

The Moghal Empire Xvi PREFACE Published in the Original Text and in Translation

The Moghal Empire xvi PREFACE published in the original text and in translation. We need better integration of the Indian and European sources by someone who reads Rajasthani, Persian, French, and Dutch, for example. For such new work our best hope lies in the originality of young historians from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Finally, my most important goal is to offer a one-volume synthesis that will be comprehensible to the non-specialist. I hope that this book can be read with profit by anyone interested in this most fascinating of historical periods. If successful, the volume should create a context for further reading and study. In writing this volume I have become deeply conscious of my debt to colleagues in this field. I am especially grateful to Irfan Habib, Ashin Das Gupta, Satish Chandra, Tapan Raychaudhuri, and M. Athar Ali for their inspired scholarship and leadership in Mughal history over the past decades. Peter Hardy and Simon Digby have provided warm support and encouragement for my work over the years. A more immediate debt is to my two fellow editors, Gordon Johnson and Christopher Bayly, for their patience and their criticism. I especially wish to thank Muzaffar Alam for his incisive comments on an earlier draft. I have also benefited from discussions with Catherine Asher, Stewart Gordon, Bruce Lawrence, Om Prakash, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, and Ellen Smart. And, as always, I must thank my wife and children for their continuing love and understanding. 1 INTRODUCTION The Mughal empire was one of the largest centralized states known in pre-modern world history. -

Rural and Tribal Societies in India

RURAL AND TRIBAL SOCIETIES IN INDIA MA SOCIOLOGY I SEMESTER (2019 Admission Onwards) (CORE COURSE) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT School of Distance Education Calicut University- P.O, Malappuram- 673635,Kerala 190354 School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT School of Distance Education Study Material MAI Semester SOCIOLOGY (2019 Admission) Core Course (SOCI C04) RURAL AND TRIBAL SOCIETIES IN INDIA Prepared by: Smt.. RANJINI.PT, Assistant Professor of Sociology, School of Distance Education, University of Calicut. Scrutinized by: Sri. Shailendra Varma R, Assistant Professor, Zamorin’s Guruvayurappan College, Calicut. Rural and Tribal Societies in India Page 2 School of Distance Education Objectives 1. To acquaint students with basics of rural and tribal societies in our country. 2. To analyze rural and tribal problems. 3. To provide knowledge of rural and tribal social institutions. MODULE 1 - RURAL AND PEASANT SOCIETY 1.1 Scope and importance of the study of rural society in India 1.2 Rural society, Peasant society, Agrarian society: Features 1.3 Perspectives on Indian village community: Historical and Ecological 1.4 Nature and changing dimensions of village society, Village studies-Marriot & Beteille MODULE 2 - CHANGING RIRAL SOCIETY 2.1 Agrarian social structure, Land ownership and agrarian relations 2.2 Emergent class relations, Decline of Agrarian economy, De-peasantization 2.3 Land reforms and its impact on rural social structure with special reference to Kerala 2.4 Migration, Globalization and rural social transformation. MODULE 3 - GOVERNANCE IN RURAL SOCIETY 3.1 Rural governance: Village Panchayath, Caste Panchayath, Dominant caste 3.2 Decentralization of power in village society, Panchayathi Raj 3.3 Community Development Programme in India 3.4 People’s Planning Programme: A critical Appraisal MODULE 4 - TRIBAL SOCIETY IN INDIA 4.1 History of Indian Tribes, Demographic features 4.2 Integration of the Tribals with the Non-tribals, Tribe-caste continuum 4.3 Tribal problems in India 4.4 Approaches, Planning and programmes for Tribal Development. -

Tribes in India 208 Reading

Department of Social Work Indira Gandhi National Tribal University Regional Campus Manipur Name of The Paper: Tribes in India (208) Semester: II Course Faculty: Ajeet Kumar Pankaj Disclaimer There is no claim of the originality of the material and it given only for students to study. This is mare compilation from various books, articles, and magazine for the students. A Substantial portion of reading is from compiled reading of Algappa University and IGNOU. UNIT I Tribes: Definition Concept of Tribes Tribes of India: Definition Characteristics of the tribal community Historical Background of Tribes- Socio- economic Condition of Tribes in Pre and Post Colonial Period Culture and Language of Major Tribes PVTGs Geographical Distribution of Tribes MoTA Constitutional Safeguards UNIT II Understanding Tribal Culture in India-Melas, Festivals, and Yatras Ghotul Samakka Sarakka Festival North East Tribal Festival Food habits, Religion, and Lifestyle Tribal Culture and Economy UNIT III Contemporary Issues of Tribes-Health, Education, Livelihood, Migration, Displacement, Divorce, Domestic Violence and Dowry UNIT IV Tribal Movement and Tribal Leaders, Land Reform Movement, The Santhal Insurrection, The Munda Rebellion, The Bodo Movement, Jharkhand Movement, Introduction and Origine of other Major Tribal Movement of India and its Impact, Tribal Human Rights UNIT V Policies and Programmes: Government Interventions for Tribal Development Role of Tribes in Economic Growth Importance of Education Role of Social Work Definition Of Tribe A series of definition have been offered by the earlier Anthropologists like Morgan, Tylor, Perry, Rivers, and Lowie to cover a social group known as tribe. These definitions are, by no means complete and these professional Anthropologists have not been able to develop a set of precise indices to classify groups as ―tribalǁ or ―non tribalǁ.