Ain't No Love in the Heart of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AWARDS 3X PLATINUM ALBUM February // 2/1/17 - 2/28/17

RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM HAMILTON//BROADWAY CAST AWARDS 3X PLATINUM ALBUM February // 2/1/17 - 2/28/17 BRUNO MARS//24K MAGIC PLATINUM ALBUM In February 2017, RIAA certified 70 Digital Single Awards and 22 Album Awards. All RIAA DIERKS BENTLEY//BLACK GOLD ALBUM Awards dating back to 1958, plus #RIAATopCertified tallies for your favorite artists, are available at DAVID BOWIE//BLACKSTAR GOLD ALBUM riaa.com/gold-platinum! KENNY CHESNEY//THE BIG REVIVAL SONGS GOLD ALBUM www.riaa.com //// //// GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS FEBRUARY // 2/1/17 - 2/28/17 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 13 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// X 21 Savage & Metro R&B/ 2/22/2017 Slaughter Gang, LLC 7/15/2016 (Feat. Future) Boomin Hip Hop R&B/ Waverecordings/Empire/ 2/3/2017 Broccoli D.R.A.M. 4/6/2016 Hip Hop Atlantic R&B/ Waverecordings/Empire/ 2/3/2017 Broccoli D.R.A.M. 4/6/2016 Hip Hop Atlantic 2/22/2017 This Is How We Roll Florida Georgia Line Country BMLG Records 12/4/2012 Jidenna Feat. Ro- R&B/ 2/2/2017 Classic Man Epic 2/3/2015 man Gianarthur Hip Hop Last Friday Night 2/10/2017 Katy Perry Pop Capitol Records 8/24/2010 (T.G.I.F) 2/3/2017 I Don’t Dance Lee Brice Country Curb Records 2/25/2014 Lil Wayne, Wiz Khal- ifa & Imagine Drag- R&B/ 2/1/2017 Sucker For Pain ons With Logic And Atlantic Records 6/24/2016 Hip Hop Ty Dolla $Ign (Feat. X Ambassadors) My Chemical 2/15/2017 Teenagers Alternative Reprise 10/20/2006 Romance 2/21/2017 Bad Blood Taylor Swift Pop Big Machine Records 10/27/2014 2/21/2017 Die A Happy Man Thomas Rhett Country Valory Music Group 9/18/2015 2/17/2017 Heathens Twenty One Pilots Alternative Atlantic Records 6/17/2016 Or Nah R&B/ 2/1/2017 (Feat. -

Midwest Choppers 2 Download Free

Midwest choppers 2 download free Artist: Tech N9ne, Song: Midwest Choppers 2 [extended](feat. K-Dean, Krayzie Bone, Twista), Duration: , Size: MB, Bitrate: kbit/sec, Type: mp3. Krayzie Bone & K-Dean) Tech N9ne - Midwest Chopper ツ Tech N9neツ - Midwest Choppers ft. D-Loc, Dalima & Big Kriz Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2(feat. Midwest Choppers 2 by Tech N9ne feat. K-Dean and Krayzie We are considering introducing an ad-free version of WhoSampled. If you would be happy to pay. Stream Tech N9ne Midwest Choppers 2 Lyrics by yancydaveoo17 from desktop or your mobile device. Download. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2. Download. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers (feat. Big Krizz Kaliko, Dalima & D-Loc). Download. Tech N9ne "Midwest Choppers 2" ft. K-Dean & Krayzie Bone iTunes - Official Hip Hop. Midwest Choppers 2 Mp3. Free download Midwest Choppers 2 Mp3 mp3 for free. Tech N9ne - Midwest Choppers 2 (ft. K-Dean & Krayzie Bone). Source. View Lyrics for Midwest Choppers 2 by Tech N9ne at AZ Lyrics Sickology Midwest Choppers 2 AZ lyrics, find other albums and lyrics for Tech. Switch browsers or download Spotify for your desktop. Midwest Choppers 2. By Tech N9ne Collabos. • 1 song, Play on Spotify. 1. Midwest Choppers. Buy Midwest Choppers 2 [Clean]: Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - Buy Midwest Choppers 2 [Explicit]: Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this song plus tens of. Fast and free Tech N9ne Midwest Choppers Instrumental YouTube to MP3. Midwest Choppers 2 Remake On Fl Studio 9(instrumental)-unfinished (OLD) Tech N9ne - Worldwide Choppers FULL Instrumental Remake (with download link). -

Power Gold: 2013’S Ins & Outs for the Second Consecutive Year, Country’S Top 100 Power Gold List Displays a Lot of Turnover from the Previous 12 Months

April 29, 2013, Issue 343 Power Gold: 2013’s Ins & Outs For the second consecutive year, Country’s Top 100 Power Gold list displays a lot of turnover from the previous 12 months. This year’s Top 100 boasts 22 new titles, compared to a whopping 33 in our April 2012 analysis and 13 new tunes in July 2011. This year’s Top 10 Power Gold is culled from Mediabase 24/7 and the Country Aircheck/Mediabase reporting panel for the week of April 21-27: 1. Kid Rock/All Summer Long 2. Zac Brown Band/Chicken Fried 3. Keith Urban/Somebody Like You 4. Alan Jackson & Jimmy Buffet/It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere 5. Dierks Bentley/What Was I Thinkin’ 6. Zac Brown Band/Toes 7. Rodney Atkins/Watching You Keith Urban Man, What Are You Doing Here? Rodeowave’s Phil Vassar (c) invites KSON/San Diego’s John & Tammy on stage while he 8. Rascal Flatts/Life Is A Highway plays “Piano Man” at the Stagecoach Country Music Festival in 9. Joe Nichols/Gimmie That Girl Indio, CA Saturday (4/27). 10. Rodney Atkins/If You’re Goin’ Through Hell New to the Top 10 are the ZBB, Flatts and Atkins tunes. Pope Finds Her Voice Sliding out of the Top 10 were Darius Rucker’s “Alright” She brought a pop-rock background and sound to The (16); Carrie Underwood’s “Before He Cheats” (15) and Voice’s Team Blake, but Cassadee Pope is now readying James Otto’s “Just Got Started Lovin’ You” (20). her Republic Nashville country debut. -

Country Superstar Kenny Chesney to Rock the 4Th of July at the 2013 Greenbrier Classic Concert Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FEBRUARY 20, 2013 COUNTRY SUPERSTAR KENNY CHESNEY TO ROCK THE 4TH OF JULY AT THE 2013 GREENBRIER CLASSIC CONCERT SERIES [White Sulphur Springs, WV] The Greenbrier, the classic American resort in White Sulphur Springs, WV, has announced that country music superstar Kenny Chesney will top a star-studded musical lineup at The Greenbrier Classic Concert Series, July 1-7, 2013, coinciding with the resort's fourth annual PGA TOUR FedExCup Event, The Greenbrier Classic. Kenny Chesney, a four-time Country Music Association and four-consecutive Academy of Country Music Entertainer of the Year, as well as the fan-voted American Music Awards Favorite Artist, is known for his high-energy concerts that regularly sell out NFL stadiums. Having recorded 19 #1s, including the multiple week chart-toppers "There Goes My Life," "Summertime," "Living in Fast Forward," "You & Tequila" and "When the Sun Goes Down," the man who's sold almost 30 million albums has become the sound of summer, good times and good friends for the 21st century. "This country is an amazing place," says Chesney. "I can see it every night at my shows: all the heart, the passion and the fun I can see out in the crowd. And to be able to spend the 4th of July somewhere as historic as The Greenbrier, that's a pretty incredible place to celebrate our nation's birthday!" "We couldn't be happier to have an American superstar like Kenny Chesney to top the bill at our Greenbrier Classic concert series," says Jim Justice, owner of The Greenbrier. -

Přírůstkový Seznam

aktualizace Rok Př. číslo Autor, interpret Název alba, kompilace ©℗ CDs X domů od: 31 873 5 Seconds of Summer 5 Seconds of Summer 2014 CD 31 512 Accept Eat the heat 2002 CD 31 473 ACDC Ballbreaker 1995 CD 31 472 ACDC Powerage 1978 CD 31 279 Adair, Beegie (+Pat Coil) Cocktail party jazz 2011 CD 31 954 Adamec, Radek Bubákov 2015 CD 5.8.2016 31 954 Adamec, Radek Bubákov 2015 CD 5.8.2016 31 571 Adamec, Radek Veselé mašinky : pohádky z depa a kolejí 2013 CD 32 109 Adele 25 2015 CD 20.8.2016 32 103 Adler-Olsen, Jussi Vzkaz v láhvi 2015 CD 2 21.9.2016 31 751 Adler-Olsen, Jussi Zabijáci : předloha filmového thrilleru 2015 CD 12.1.2016 31 280 Aiken, Clay A thousand different ways 2006 CD 31 281 Aiken, Clay Measure of a man 2003 CD 31 675 Albarn, Damon Everyday robots 2014 CD 31 391 Aldort, Naomi Vychováváme děti a rosteme s nimi 2014 CD 31 967 Aleš Brichta Project Anebo taky datel 2015 CD 11.3.2016 31 130 Aleš Brichta Project Údolí sviní 2013 CD 31 397 Allen, Lily Sheezus 2014 CD 32 110 Allison, Bernard In the mix 2015 CD 16.10.2015 32 263 Allman, Gregg All my friends : celebrating the songs & 2014 CD 2 voice of Gregg Allman 32 206 Allman, Gregg Laid back 1973 CD 32 264 Allman, Gregg Low country blues 2011 CD 31 513 Alter Bridge Fortress 2013 CD 31 155 Al-Yaman Insanyya 2009 CD 31 851 Anderson, Jon The Promise ring 1997 CD 31 715 Anderson-Lopez, Kristen Frozen : Ledové království 2013 CD 31 633 Andrews, Troy Backatown 2010 CD 31 634 Andrews, Troy For true 2011 CD 31 635 Andrews, Troy Say that to say this 2013 CD 31 240 Anna K. -

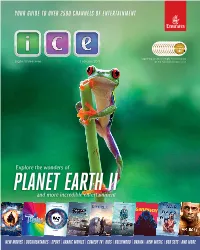

Your Guide to Over 2500 Channels of Entertainment

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment Digital Widescreen February 2017 for the 12th consecutive year! PLANET Explore the wonders ofEARTH II and more incredible entertainment NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE ENTERTAINMENT An extraordinary experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. 496 movies Information… Communication… Entertainment… THE LATEST MOVIES Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 STAY CONNECTED ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS Connect to the OnAir Wi-Fi 4 103 network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s Move around 1 Choose a channel using the games Go straight to your chosen controller pad programme by typing the on your handset channel number into your and select using 2 3 handset, or use the onscreen the green game channel entry pad button 4 1 3 Swipe left and right like Search for movies, a tablet. Tap the arrows TV shows, music and ĒĬĩĦĦĭ onscreen to scroll system features ÊÉÏ 2 4 Create and access Tap Settings to Português, Español, Deutsch, 日本語, Français, ̷͚͑͘͘͏͐, Polski, 中文, your own playlist adjust volume and using Favourites brightness Many movies are available in up to eight languages. -

1 - Radio’S Place in the Media Landscape I

1 - Radio’s Place in the Media Landscape I ARBITRON: "RADIO LISTENING IS UP" 6-12-13 Arbitron released another RADAR National Radio Listening Report today. The report says radio’s audience increased year over year, adding more than 430,000 weekly listeners. Arbitron says radio now reaches 242.5 million listeners, or 92 percent of persons 12 and older, on an average weekly basis. Additionally, daily time spent listening to radio among persons age 12 and older held steady versus the June 2012 RADAR report. People 12 and older spend approximately 2 hours and 36 minutes a day with radio. Why Gen Y We can throw the 93% number around all we like, but the bottom line is that radio listening levels vary depending on the group you’re looking at. In a recent series of posts, we’ve talked about the concerning radio problem centering on lost youth – specifically, the notion that the medium has lost a generation of listeners over the past decade or so. Some might argue that we’re actually talking about two generations that are simply not as engaged with radio as their parents. Gen Y – or Millennials – is a case in point. Here’s their Media Usage Pyramid from Techsurvey9. A look at the black bar below indicates that 86% of these twenty and thirtysomethings listen to radio an hour a day or more. That’s below the study average of 89%. And this pattern intensifies when we examine Gen Z – those 20 and younger. Only 78% of them listen to broadcast radio for that one hour minimum a day. -

2O16 Midwest Duet/Trio Competition

2O16 MIDWEST DUET/TRIO COMPETITION ENTRY FEE: 2016 SUMMER BPP CAMPER ENTRY: $ 45 per DUET and $ 65 per TRIO NON-CAMPER ENTRY: $ 55 per DUET and $ 75 per TRIO SITE: Saturday, August 20th ~ Renaissance Hotel & Convention Center Ballroom QUALIFICATIONS: 2 or 3 Performers Dance length -1:15 maximum Entrance/Exit - Walk on to performing area. No Props. Music - CD recorded at the beginning, single track and labeled with selection title. JUDGING AREAS: Choreography - Appropriate for family audience. Routine emphasis should be on creative pom and dance choreography which is centered around the performer’s strengths. Overall choreography should “USE” each member, rather than a routine completely in unison or simple opposition. A good question to ask is, “… if one performer was taken away, would routine have the same effect?” Standard uniform or dance clothing may be worn. No exposed midriffs. Music Selection - Inappropriate lyrics or movement will result in disqualification/ penalty. ENTRY DEADLINE: ONLY MAIL entries will be accepted from July 20th – August 8th! Your competition number and time slot will be posted on the website (Competition page) starting on August 15th, www.badgerettepompon.com AWARDS: Trophies will be awarded to the top five Duet/Trio Performances! Semi-Finalist routines will be rejudged SATURDAY following team performances at Harper Overall Awards to be presented: 1st /$100 2nd /$75 3rd /$50 4th 5th SPECIAL DISNEY HONOR: The Champion Duet/Trio will be invited to perform on the 2017 Badgerette Disney All*Star Talent Tour ~ 20th Anniversary Celebration! 2016 BADGERETTE MIDWEST CHAMPIONSHIP DUET/TRIO REGISTRATION TEAM NAME ___________________________________________________________________________________ DANCERS NAMES ______________________________________ ____________________________________ ______________________________________ *Please note dancers in multiple Duet/Trios? 2016 CAMPER DUET @ $ 45=_______ -OR- TRIO @ $ 65=________ enc. -

Kenny Chesney and Darius Rucker to Appear at 2014 Honors Gala

For Immediate Release Contact: Luke Arterburn The Andrews Agency 615-242-4400 [email protected] Tinti Moffat T.J. Martell Foundation [email protected] Kenny Chesney and Darius Rucker to appear at 2014 Honors Gala Chesney and Rucker will pay tribute to Honorees: Mark Bloom, Beth Dortch Franklin, Scott Hiebert, Mike Dungan and Dale Morris NASHVILLE, Tenn. – January 3, 2014 – The T.J. Martell Foundation announced today two of the stars that are slated to make special appearances at the sixth annual Nashville Honors Gala. Country music recording artists Kenny Chesney and Darius Rucker will make special appearances at the gala, which will be held at the Nashville Omni Hotel on March 10, 2014. This year’s high profile affair will recogniZe individuals who have made significant contributions to the music industry, the Nashville economy and medical research. Honorees are Nashville real estate visionary Mark Bloom, music industry icons Dale Morris and Mike Dungan, entrepreneur Beth Dortch Franklin and cancer research pioneer Scott Hiebert. The T.J. Martell Foundation’s Nashville Honors Gala is a high-profile festive affair, which brings together celebrities with business, medical, sports and entertainment industry leaders to raise awareness and funds for innovative cancer research at 11 top research hospitals in the United States including the Frances Williams Preston Laboratories at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center. “We are so excited that Kenny Chesney and Darius Rucker will be appearing to pay tribute to our honorees and to help support the wonderful work of the T.J. Martell Foundation,” said T.J. Martell’s Director of Strategic Development, Tinti Moffat. -

Top 40 UPDATE BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS BILLBOARD.BIZ/NEWSLETTER JUNE 6, 2013 | PAGE 1 of 9

MID WEEK Top 40 UPDATE BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS BILLBOARD.BIZ/NEWSLETTER JUNE 6, 2013 | PAGE 1 OF 9 INSIDE Top 40 And Radio Geeks, Unite! The Connected Consumer PAGE 3 RICH APPEL [email protected] What’s With a multitude of entertainment options out there, it’s easy to YOUNGER = HIGHER, LONGER, MORE New At forget that in top 40’s long history, a listener’s favorite station has Who are top 40’s P1s, and how engaged are they in the digital uni- The New never been the only game in town. There was always something verse? According to Edison Research VP Jason Hollins, 60% are Music else a consumer could do. Not to mention there are only so many female, 50% are age 12-24 and 60% 12-34, with an average age of hours in a day, right? 28. This younger skew means a greater Seminar The good news suggested by the HOW TOP 40’S P1s COMPARE TO THE POPULATION level of connectivity compared with PAGE 4 PERSONS TOP 40 Infinite Dial’s study of the format’s 12+ P1s not just other formats but to the 12- P1s—released last week by Edi- AM/FM radio usage in car 84% 88% plus and 12-34 population in general. Macklemore son Research and Arbitron—is that Awareness of Pandora 69% 88% Nearly 80% of P1s have Internet ac- & Ryan Lewis there seems to be plenty of room— Having a profile on any social network 62% 82% cess and use Wi-Fi, and one-third own and time—for all players. -

Police React to Violent Crowd with Tear

OREGON DAILY Emerald DAILYEMERALD . COM THE INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER AT THE UNIVERSITY OF OREGON SINCE 1900 VOL. 112. ISSUE 16 MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2010 KWVA’S TOP 10 BACK DUCKS DEMOLISH ASU DORM FOOD TO SCHOOL ALBUMS LaMichael James runs rampant as Going back to the residence SCENE | PAGE 8 Oregon opens conference play in style halls — for the menu SUMMER SENATE NEEDS PAY SPORTS | PAGE 11 SCENE | PAGE 7 OPINION | PAGE 2 CRIME LOCAL Police react to violent Fairmount fresh crowd with tear gas Several arrested at 400-person riot Friday in West University area MAT WOLF NEWS REPORTER A large street party became a violent confrontation between approximately 400 students and local law enforcement agencies on September 25. Eugene Police Department “party patrols” responded to the intersection of 13th Avenue and Ferry Street at 11:21 p.m., to where there was a large gathering of an estimated 400 individuals. The latest EPD reports count nine individuals arrested in relation to the event. Police responded to the scene by launching four teargas canisters and Lane County Sheriff deputies discharged one non-lethal rubber pellet round. Police press releases identified at least nine individuals, all in their late teens and early twenties, as having been arrested and taken into custody as a result of Friday’s incident. According to official EPD press releases, two individuals were arrested in direct connection to the initial clashes with police following the use of tear gas. The first of the two individuals is Odin VanNorman Erickson, 24, on charges of riot, interfering with ALEX MCDOUGALL PHOTOGRAPHER police, third degree criminal mischief and possession Tom Murray of Seasonal Local Organic Farm answers a question about his farm-grown tomatoes at the Fairmount Farmers Market. -

Eminem Steppin Onto the Scene Tracklist

Eminem steppin onto the scene tracklist click here to download Bassmint Productions – none. Fattest Skinny Kid Alive. If the tape is being sold from the UK, buy with extreme caution because the UK is infamous for selling fake tapes. Find a Bassmint Productions - Steppin' On To The Scene first pressing or reissue. Complete your Bassmint Productions collection. Shop Vinyl and CDs. Bassmint Productions – Steppin' On To The Scene. Genre: Hip Hop. Style: Hardcore Hip-Hop. Year: Tracklist Eminem - Steppin up onto the scene [ VERY RARE] Eminem - Fattest skinny kid alive [VERY RARE] Chaos Kid - Enuff Is Enuff - (Chaos Side) Soul Intent/Bassmint Productions Chaos Kid. Steppin' On To the Scene is the debut EP by local American hip hop group Bassmint Productions, who morphed into Soul Intent in This EP was produced. Soul Intent was an American hip hop group, and consisted of Eminem, Proof, Chaos Kid, Manix and DJ Butter Fingers. They were previously Bassmint Productions between and Contents. 1 Early years: Bassmint Productions; 2 From Soul Intent; 3 Discography. Steppin' On To The Scene () a few homemade/handmade demo tapes, including Steppin' onto the Scene. Tracklist with lyrics of the album STEPPIN' ONTO THE SCENE [] from Soul Intent: Steppin' On To The Scene - Fattest Skinny Kid Alive - Under New. Title, Artist, Rating, Length. 1 · Steppin' On To The Scene · Eminem?:?? 2 · Fattest Skinny Kid Alive · Eminem?:?? 3 · Under New Managment. Style-O-Maniac [Chaos Kid] download; www.doorway.ru Is Enuff [Chaos Kid] (feat. Delirious D) download; www.doorway.ru Have Mercy [Chaos Kid] download; 4. "Steppin' onto the Scene" 2.