Elite Politics and Dissent in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combating the Drug Menace Together

www.thehindu.com 2018-07-22 Combating the drug menace together Even as Colombo steps up efforts to combat drug peddling in the country, authorities have turned to India for help to address what has become a shared concern for the neighbours. Sri Lanka police’s narcotics bureau, amid frequent hauls and arrests, is under visible pressure to tackle the growing drug menace. President Maithripala Sirisena, who controversially spoke of executing drug convicts, has also taken efforts to empower the tri-forces to complement the police’s efforts to address the problem. Further, recognising that drugs are smuggled by air and sea from other countries, Sri Lanka is now considering a larger regional operation, with Indian assistance. “We intend to initiate dialogue with the Indian authorities to get their assistance. We need their help in identifying witnesses needed in our local investigations into smuggling activities,” Law and Order Minister Ranjith Madduma Bandara told local media recently. India’s role, top officials here say, will be “crucial”. The conversation between the two countries has been going on for some time now, after the neighbours signed an agreement on Combating International Terrorism and Illicit Drug Trafficking in 2013, but the problem has grown since. Appreciating the urgency of the matter, top cops from the narcotics control bureaus of India and Sri Lanka, who met in New Delhi in May, decided to enhance cooperation to combat drug crimes. Following up, Colombo has sought New Delhi’s assistance to trace two underworld drug kingpins, believed to be in hiding in India, according to narcotics bureau chief DIG Sajeewa Medawatta. -

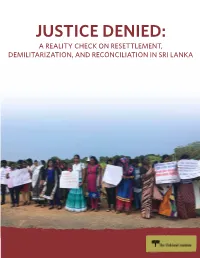

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Chandrika Kumaratunga (Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga)

Chandrika Kumaratunga (Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga) Sri Lanka, Presidenta de la República; ex primera ministra Duración del mandato: 12 de Noviembre de 1994 - de de Nacimiento: Colombo, Western Province, 29 de Junio de 1945 Partido político: SLNP ResumenLa presidenta de Sri Lanka entre 1994 y 2005 fue el último eslabón de una dinastía de políticos que, como es característico en Asia Indostánica, está familiarizada con el poder tanto como la tragedia. Huérfana del asesinado primer ministro Solomon Bandaranaike, hija de la tres veces primera ministra Sirimavo Bandaranaike ?con la que compartió el Ejecutivo en su primer mandato, protagonizando las dos mujeres un caso único en el mundo- y viuda de un político también asesinado, Chandrika Kumaratunga heredó de aquellos el liderazgo del izquierdista Partido de la Libertad (SLNP) e intentó, infructuosamente, concluir la sangrienta guerra civil con los separatistas tigres tamiles (LTTE), iniciada en 1983, por las vías de una reforma territorial federalizante y la negociación directa. http://www.cidob.org 1 of 10 Biografía 1. Educación política al socaire de su madre gobernante 2. Primera presidencia (1994-1999): plan de reforma territorial para terminar con la guerra civil 3. Segunda presidencia (1999-2005): proceso de negociación con los tigres tamiles y forcejeos con el Gobierno del EJP 1. Educación política al socaire de su madre gobernante Único caso de estadista, mujer u hombre, hija a su vez de estadistas en una república moderna, la suya es la familia más ilustre de la élite dirigente -

Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism

DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM SRI LANKAN DISCOURSES OF ETHNO-NATIONALISM AND RELIGIOUS FUNDAMENTALISM By MYRA SIVALOGANATHAN, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Myra Sivaloganathan, June 2017 M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Sri Lankan Discourses of Ethno-Nationalism and Religious Fundamentalism AUTHOR: Myra Sivaloganathan, B.A. (McGill University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Mark Rowe NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 91 ii M.A. Thesis – Myra Sivaloganathan; McMaster University – Religious Studies. Abstract In this thesis, I argue that discourses of victimhood, victory, and xenophobia underpin both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalist and religious fundamentalist movements. Ethnic discourse has allowed citizens to affirm collective ideals in the face of disparate experiences, reclaim power and autonomy in contexts of fundamental instability, but has also deepened ethnic divides in the post-war era. In the first chapter, I argue that mutually exclusive narratives of victimhood lie at the root of ethnic solitudes, and provide barriers to mechanisms of transitional justice and memorialization. The second chapter includes an analysis of the politicization of mythic figures and events from the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahāvaṃsa in nationalist discourses of victory, supremacy, and legacy. Finally, in the third chapter, I explore the Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam’s (LTTE) rhetoric and symbolism, and contend that a xenophobic discourse of terrorism has been imposed and transferred from Tamil to Muslim minorities. Ultimately, these discourses prevent Sri Lankans from embracing a multi-ethnic and multi- religious nationality, and hinder efforts at transitional justice. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 62.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, March 25, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 62 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. Sisira Jayakody, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Promotion, Rural and Ayurvedic Hospitals Development and Community Health Hon. -

Strategic Plan 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020

STRATEGIC PLAN STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 ELECTION COMMISSION OF SRI LANKA 2017-2020 Department of Government Printing STRATEGIC PLAN 2017-2020 Election Commission of Sri Lanka Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) of the Election Commission of Sri Lanka for 2017-2020 “Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives... The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will, shall be expressed in periodic ndenineeetinieniendeend shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.” Article 21, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 Participatory Strategic Plan (PSP) Election Commission of Sri Lanka 2017-2020 I Foreword By the Chairman and the Members of the Commission Mahinda Deshapriya N. J. Abeysekere, PC Prof. S. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole Chairman Member Member The Soulbury Commission was appointed in 1944 by the British Government in response to strong inteeneeinetefittetetenteineentte population in the governance of the Island, to make recommendations for constitutional reform. The Soulbury Commission recommended, interalia, legislation to provide for the registration of voters and for the conduct of Parliamentary elections, and the Ceylon (Parliamentary Election) Order of the Council, 1946 was enacted on 26th September 1946. The Local Authorities Elections Ordinance was introduced in 1946 to provide for the conduct of elections to Local bodies. The Department of Parliamentary Elections functioned under a Commissioner to register voters and to conduct Parliamentary elections and the Department of Local Government Elections functioned under a Commissioner to conduct Local Government elections. The “Department of Elections” was established on 01st of October 1955 amalgamating the Department of Parliamentary Elections and the Department of Local Government Elections. -

Ranil Wickremesinghe Sworn in As Prime Minister

September 2015 NEWS SRI LANKA Embassy of Sri Lanka, Washington DC RANIL WICKREMESINGHE VISIT TO SRI LANKA BY SWORN IN AS U.S. ASSISTANT SECRETARIES OF STATE PRIME MINISTER February, this year, we agreed to rebuild our multifaceted bilateral relationship. Several new areas of cooperation were identified during the very successful visit of Secretary Kerry to Colombo in May this year. Our discussions today focused on follow-up on those understandings and on working towards even closer and tangible links. We discussed steps U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for taken by the Government of President South and Central Asian Affairs Nisha Maithripala Sirisena to promote recon- Biswal and U.S. Assistant Secretary of ciliation and to strengthen the rule of State for Democracy, Human Rights law as part of our Government’s overall Following the victory of the United National Front for and Labour Tom Malinowski under- objective of ensuring good governance, Good Governance at the general election on August took a visit to Sri Lanka in August. respect for human rights and strength- 17th, the leader of the United National Party Ranil During the visit they called on Presi- ening our economy. Wickremesinghe was sworn in as the Prime Minister of dent Maithirpala Sirisena, Prime Min- Sri Lanka on August 21. ister Ranil Wickremesinghe and also In keeping with the specific pledge in After Mr. Wickremesinghe took oaths as the new met with Minister of Foreign Affairs President Maithripala Sirisena’s mani- Prime Minister, a Memorandum of Understanding Mangala Samaraweera as well as other festo of January 2015, and now that (MoU) was signed between the Sri Lanka Freedom government leaders. -

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Edited by Asanga Welikala Volume 2 18 Failure of Quasi-Gaullist Presidentialism in Sri Lanka Suri Ratnapala Constitutional Choices Sri Lanka’s Constitution combines a presidential system selectively borrowed from the Gaullist Constitution of France with a system of proportional representation in Parliament. The scheme of proportional representation replaced the ‘first past the post’ elections of the independence constitution and of the first republican constitution of 1972. It is strongly favoured by minority parties and several minor parties that owe their very existence to proportional representation. The elective executive presidency, at least initially, enjoyed substantial minority support as the president is directly elected by a national electorate, making it hard for a candidate to win without minority support. (Sri Lanka’s ethnic minorities constitute about 25 per cent of the population.) However, there is a growing national consensus that the quasi-Gaullist experiment has failed. All major political parties have called for its replacement while in opposition although in government, they are invariably seduced to silence by the fruits of office. Assuming that there is political will and ability to change the system, what alternative model should the nation embrace? Constitutions of nations in the modern era tend fall into four categories. 1.! Various forms of authoritarian government. These include absolute monarchies (emirates and sultanates of the Islamic world), personal dictatorships, oligarchies, theocracies (Iran) and single party rule (remaining real or nominal communist states). 2.! Parliamentary government based on the Westminster system with a largely ceremonial constitutional monarch or president. Most Western European countries, India, Japan, Israel and many former British colonies have this model with local variations. -

Endgame in Sri Lanka Ajit Kumar Singh*

Endgame in Sri Lanka Ajit Kumar Singh* If we do not end war – war will end us. Everybody says that, millions of people believe it, and nobody does anything. – H.G. Wells 1 The Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapakse finally ended the Eelam War2 in May 2009 – though, perhaps, not in the manner many would desire. So determined was the President that he had told Roland Buerk of the BBC in an interview published on February 21, 2007, “I don't want to pass this problem on to the next generation.”3 Though the final phase of open war4 began on January 16, 2008, following the January 2 unilateral withdrawal of the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) from the Norway-brokered * Ajit Kumar Singh, Research Fellow, Institute for Conflict Management 1 Things to Come (The film story), Part III, adapted from his 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, spoken by the character John Cabal. 2 The civil war in Sri Lanka can be divided into four phases: Eelam War I between 1983 and 1987, Eelam War II between 1990-1994, Eelam War III between 1995-2001, and Eelam War IV between 2006-2009. See Muttukrishna Sarvananthaa in “Economy of the Conflict Region in Sri Lanka: From Embargo to Repression”, Policy Studies 44, East-West Centre, http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs/ps044.pdf. 3 “No end in sight to Sri Lanka conflict”, February 21, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6382787.stm. 4 Amantha Perera, “Sri Lanka: Open War”, South Asia Intelligence Review, Volume 6, No.28, http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/sair/Archives/6_28.htm#assessment1. -

DIDR, Sri Lanka

SRI LANKA Note 23 mars 2016 Les changements politiques intervenus en 2015 Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Résumé : En 2005 les élections présidentielles et législatives ont porté au gouvernement une nouvelle coalition de partis politiques dominée par le Parti national uni et à la présidence un dirigeant du Parti sri lankais de la liberté, Maithripala Sirisena. -

Volume of Abstracts

International Postgraduate Research Conference 2015 University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka Conference Programme 10th – 11th December Faculty of Graduate Studies University of Kelaniya Sri Lanka www.kln.ac.lk/fgs 1 IPRC – 2015 Conference Organizing Committee Convener: Senior Professor Sunanda Maddumabandara Vice Chancellor University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka Conference Chair: Senior Professor Kulasena Vidanagamage Overall Co-ordinator: Professor Chamindi Dilkushi Wettewe Faculty Co -ordinators: Faculty of Commerce & Management Studies: Dr. D.K.Y. Abeywardhana Faculty of Graduate Studies: Mr. Shakya Lakmal Wijerathne Faculty of Humanities: Ms.Prabha Manuratne Faculty of Medicine: Dr.C.W. Subasinghe Faculty of Science: Dr.V.P.A. Weerasinghe Faculty of Social Sciences: Dr.M.G.Kularatne Co-ordinator International participants: MrThilina Wickramarachchi Conference Secretary: Mr.Ishara Thilakarathne Assistant Secretary: Mr. Dimuth Sahajeewa Contact Persons Professor Chamindi Dilkushi Wettewe +94 112903782 [email protected] Mr.Ishara Thilakarathne +94 715873619 [email protected] / [email protected] Mr. Dimuth Sahajeewa +94 715982668 [email protected] 2 Ta Table of Content Table of Content ........................................................................................................................ 3 A Review of Capital Structure Theories .................................................................................. 17 A Study on Brand Equity Antecedents on Purchasing Intention for Application Based Cement (ABC) Brands in Sri -

Sugathapala Mendis and Another V Chandrika Kumaratunga and Others S C ( Waters Edge Case) 339

Sugathapala Mendis and Another v Chandrika Kumaratunga and Others S C ( Waters Edge Case) 339 SUGATHAPALA MENDIS AND ANOTHR V CHANDRIKA KUMARATUNGA AND OTHERS (WATERS EDGE CASE) SUPREME COURT S.N. SILVA, C.J. TILAKAWARDANE, J RATNAYAKE, J. SC FR 352/07. MAY 29, 2008 JUNE 25, 26, 2008 JULY 14, 31,2008 Fundamental Rights - Article 12(1) - Public Interest litigation - Time limit - locus standi - Doctrine of Public Trust - Violation - Is the President subject to the Rule of the Law? - What is public purpose requirement? The petitioners/lntervenient petitioners complained of infringement pertaining to the acquisition of land on the premise that such land would be utilized to serve a public purpose whereas by the impugned executive or administrative action the land was knowingly, deliberately and manipulatively sold to a private entrepreneur to serve as an exclusive private golf resort in Sri Lanka. It was contented that, this was done through a process thatwas conniving and contrary to the equal protection of the law guaranteed by Article 12(1) of the Constitution which assures to the people the Rule of Law. It was further contended that those alleged to have initiated, facilitated and or empowered to achieve this outcome were those from the highest echelons of the executive and included senior officials members of the public sector, statutory bodies of the government, the former President (1st respondent) high government agencies. Held: (1) The Nature of large scale developments is that they occur over-time. In the instant case, though communication with UDA commenced in1997, completion of the project was delegated extensions granted and particulars changed, such that the project at the time this claim was brought remained unfinished.