C.A WRIT 380/2017. Kotagala Plantations PLC Vs. H.A. Kamal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combating the Drug Menace Together

www.thehindu.com 2018-07-22 Combating the drug menace together Even as Colombo steps up efforts to combat drug peddling in the country, authorities have turned to India for help to address what has become a shared concern for the neighbours. Sri Lanka police’s narcotics bureau, amid frequent hauls and arrests, is under visible pressure to tackle the growing drug menace. President Maithripala Sirisena, who controversially spoke of executing drug convicts, has also taken efforts to empower the tri-forces to complement the police’s efforts to address the problem. Further, recognising that drugs are smuggled by air and sea from other countries, Sri Lanka is now considering a larger regional operation, with Indian assistance. “We intend to initiate dialogue with the Indian authorities to get their assistance. We need their help in identifying witnesses needed in our local investigations into smuggling activities,” Law and Order Minister Ranjith Madduma Bandara told local media recently. India’s role, top officials here say, will be “crucial”. The conversation between the two countries has been going on for some time now, after the neighbours signed an agreement on Combating International Terrorism and Illicit Drug Trafficking in 2013, but the problem has grown since. Appreciating the urgency of the matter, top cops from the narcotics control bureaus of India and Sri Lanka, who met in New Delhi in May, decided to enhance cooperation to combat drug crimes. Following up, Colombo has sought New Delhi’s assistance to trace two underworld drug kingpins, believed to be in hiding in India, according to narcotics bureau chief DIG Sajeewa Medawatta. -

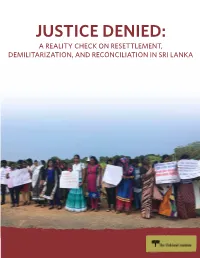

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Ranil Wickremesinghe Sworn in As Prime Minister

September 2015 NEWS SRI LANKA Embassy of Sri Lanka, Washington DC RANIL WICKREMESINGHE VISIT TO SRI LANKA BY SWORN IN AS U.S. ASSISTANT SECRETARIES OF STATE PRIME MINISTER February, this year, we agreed to rebuild our multifaceted bilateral relationship. Several new areas of cooperation were identified during the very successful visit of Secretary Kerry to Colombo in May this year. Our discussions today focused on follow-up on those understandings and on working towards even closer and tangible links. We discussed steps U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for taken by the Government of President South and Central Asian Affairs Nisha Maithripala Sirisena to promote recon- Biswal and U.S. Assistant Secretary of ciliation and to strengthen the rule of State for Democracy, Human Rights law as part of our Government’s overall Following the victory of the United National Front for and Labour Tom Malinowski under- objective of ensuring good governance, Good Governance at the general election on August took a visit to Sri Lanka in August. respect for human rights and strength- 17th, the leader of the United National Party Ranil During the visit they called on Presi- ening our economy. Wickremesinghe was sworn in as the Prime Minister of dent Maithirpala Sirisena, Prime Min- Sri Lanka on August 21. ister Ranil Wickremesinghe and also In keeping with the specific pledge in After Mr. Wickremesinghe took oaths as the new met with Minister of Foreign Affairs President Maithripala Sirisena’s mani- Prime Minister, a Memorandum of Understanding Mangala Samaraweera as well as other festo of January 2015, and now that (MoU) was signed between the Sri Lanka Freedom government leaders. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 70. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, May 18, 2016 at 1.00 p.m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and the Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and the Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration and Management Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa, Minister of Disaster Management ( 2 ) M. No. 70 Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Law and Order and Southern Development Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Ports and Shipping Hon. Patali Champika Ranawaka, Minister of Megapolis and Western Development Hon. Chandima Weerakkody, Minister of Petroleum Resources Development Hon. Malik Samarawickrama, Minister of Development Strategies and International Trade Hon. -

Justice Delayed, Justice Denied? the Search for Accountability for Alleged Wartime Atrocities Committed in Sri Lanka

Pace International Law Review Volume 33 Issue 2 Spring 2021 Article 3 May 2021 Justice Delayed, Justice Denied? The Search for Accountability for Alleged Wartime Atrocities Committed in Sri Lanka Aloka Wanigasuriya University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Humanitarian Law Commons, International Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Aloka Wanigasuriya, Justice Delayed, Justice Denied? The Search for Accountability for Alleged Wartime Atrocities Committed in Sri Lanka, 33 Pace Int'l L. Rev. 219 (2021) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr/vol33/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace International Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTICE DELAYED, JUSTICE DENIED? THE SEARCH FOR ACCOUNTABILITY FOR ALLEGED WARTIME ATROCITIES COMMITTED IN SRI LANKA Aloka Wanigasuriya* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................................................... 221 II. National Action ..................................................................... 223 A. National Mechanisms............................................... 223 1. Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka (HRCSL) .............................................................. -

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Edited by Asanga Welikala Volume 2 18 Failure of Quasi-Gaullist Presidentialism in Sri Lanka Suri Ratnapala Constitutional Choices Sri Lanka’s Constitution combines a presidential system selectively borrowed from the Gaullist Constitution of France with a system of proportional representation in Parliament. The scheme of proportional representation replaced the ‘first past the post’ elections of the independence constitution and of the first republican constitution of 1972. It is strongly favoured by minority parties and several minor parties that owe their very existence to proportional representation. The elective executive presidency, at least initially, enjoyed substantial minority support as the president is directly elected by a national electorate, making it hard for a candidate to win without minority support. (Sri Lanka’s ethnic minorities constitute about 25 per cent of the population.) However, there is a growing national consensus that the quasi-Gaullist experiment has failed. All major political parties have called for its replacement while in opposition although in government, they are invariably seduced to silence by the fruits of office. Assuming that there is political will and ability to change the system, what alternative model should the nation embrace? Constitutions of nations in the modern era tend fall into four categories. 1.! Various forms of authoritarian government. These include absolute monarchies (emirates and sultanates of the Islamic world), personal dictatorships, oligarchies, theocracies (Iran) and single party rule (remaining real or nominal communist states). 2.! Parliamentary government based on the Westminster system with a largely ceremonial constitutional monarch or president. Most Western European countries, India, Japan, Israel and many former British colonies have this model with local variations. -

Country of Origin Information Report Sri Lanka March 2008

COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT SRI LANKA 3 MARCH 2008 Border & Immigration Agency COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION SERVICE 3 MARCH 2008 SRI LANKA Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN SRI LANKA, FROM 1 FEBRUARY TO 27 FEBRUARY 2008 REPORTS ON SRI LANKA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 1 FEBRUARY AND 27 FEBRUARY 2008 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY........................................................................................ 1.01 Map ................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY............................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY.............................................................................................. 3.01 The Internal conflict and the peace process.............................. 3.13 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS...................................................................... 4.01 Useful sources for updates ......................................................... 4.18 5. CONSTITUTION..................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .............................................................................. 6.01 Human Rights 7. INTRODUCTION..................................................................................... 7.01 8. SECURITY FORCES............................................................................... 8.01 Police............................................................................................ -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 134. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, December 06, 2016 at 9.30 a. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development and Christian Religious Affairs and Minister of Lands Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Co-existence, Dialogue and Official Languages Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Palany Thigambaram, Minister of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure and Community Development Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare ( 2 ) M. No. 134 Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 73.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, May 04, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Deputy Speaker and the Chair of Committees Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Rajapaksa, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Minister of Buddhasasana, Religious & Cultural Affairs and Minister of Urban Development & Housing Hon. Rohitha Abegunawardhana, Minister of Ports & Shipping Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. S. M. Chandrasena, Minister of Lands Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Douglas Devananda, Minister of Fisheries Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. (Prof.) G. L. Peiris, Minister of Education Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. Keheliya Rambukwella, Minister of Mass Media Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Namal Rajapaksa, Minister of Youth & Sports Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. (Mrs.) Pavithradevi Wanniarachchi, Minister of Health Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice ( 2 ) M. No. 73 Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection Hon. -

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sri Lanka Annual Performance

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS SRI LANKA ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2017 MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Contents Page No 1. Mission, Subjects and Functions of the Ministry of Foreign 1 Affairs 2. Preface 3 - 5 3. Organizational Chart of the Ministry 7 4. Progress Report of the Divisions - Africa Division 9 - 27 - Consular Affairs Division 29 - 35 - East Asia and Pacific Division 37 - 80 - Economic Affairs and Trade Division 81 - 88 - European Union, Multilateral Treaties and Commonwealth 89 - 95 Division - Finance Division 97 - 102 - General Administration Division 103 - 106 - Legal Division 107 - 112 - Middle East 113 - 134 - Ocean Affairs and Climate Change Division 135 - 142 - Overseas Administration Division 143 - 149 - Overseas Sri Lankan Division 151 - 154 - Policy Planning Division 155 - 157 - Protocol Division 159 - 167 - Public Communications Division 169 - 172 - South Asia and SAARC Division 173 - 184 - United Nations and Human Rights Division 185 - 192 - United States of America and Canada Division 193 - 201 - West Division 203 - 229 5. Network of Diplomatic Missions Abroad 231 6. Revenue collected by Sri Lanka Missions Abroad in 2017 233 - 235 7. Consular activities carried out by Sri Lanka Missions Abroad - 236 - 238 2017 Vision To be a responsible nation within the international community and to maintain friendly relations with all countries. Mission The Promotion, Projection and Protection of Sri Lanka’s national interests internationally, in accordance with the foreign policy of the Government and to advise the Government on managing foreign relations in keeping with Sri Lanka’s national interests. Subjects and Functions of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Implementation of political plans and programmes in respect of Foreign Affairs; Representation of Sri Lanka abroad; International Agreements and Treaties; Foreign Government and international organization’s representation in Sri Lanka; External publicity; Diplomatic immunities and privileges and Consular functions. -

Majoritarian Politics in Sri Lanka: the ROOTS of PLURALISM BREAKDOWN

Majoritarian Politics in Sri Lanka: THE ROOTS OF PLURALISM BREAKDOWN Neil DeVotta | Wake Forest University April 2017 I. INTRODUCTION when seeking power; and the sectarian violence that congealed and hardened attitudes over time Sri Lanka represents a classic case of a country all contributed to majoritarianism. Multiple degenerating on the ethnic and political fronts issues including colonialism, a sense of Sinhalese when pluralism is deliberately eschewed. At Buddhist entitlement rooted in mytho-history, independence in 1948, Sinhalese elites fully economic grievances, politics, nationalism and understood that marginalizing the Tamil minority communal violence all interacting with and was bound to cause this territorialized community stemming from each other, pushed the island to eventually hit back, but they succumbed to towards majoritarianism. This, in turn, then led to ethnocentrism and majoritarianism anyway.1 ethnic riots, a civil war accompanied by terrorism What were the factors that motivated them to do that ultimately killed over 100,000 people, so? There is no single explanation for why Sri democratic regression, accusations of war crimes Lanka failed to embrace pluralism: a Buddhist and authoritarianism. revival in reaction to colonialism that allowed Sinhalese Buddhist nationalists to combine their The new government led by President community’s socio-economic grievances with Maithripala Sirisena, which came to power in ethnic and religious identities; the absence of January 2015, has managed to extricate itself minority guarantees in the Constitution, based from this authoritarianism and is now trying to on the Soulbury Commission the British set up revive democratic institutions promoting good prior to granting the island independence; political governance and a degree of pluralism. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 133. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Monday, December 05, 2016 at 9.30 a. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees His Excellency Maithripala Sirisena, President of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, Minister of Defence, Minister of Mahaweli Development and Environment and Minister of National Integration and Reconciliation Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and Chief Government Whip Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. R. M. Ranjith Madduma Bandara, Minister of Public Administration and Management Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa, Minister of Disaster Management Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Law and Order and Southern Development Hon. Arjuna Ranatunga, Minister of Ports and Shipping ( 2 ) M. No. 133 Hon. Mahinda Samarasinghe, Minister of Skills Development and Vocational Training Hon. Ranjith Siyambalapitiya, Minister of Power and Renewable Energy Hon. (Dr.) Rajitha Senaratne, Minister of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine Hon. Wijith Wijayamuni Zoysa, Minister of Irrigation and Water Resources Management Hon.