Dan Davin Re-Visited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE NEW ZEALA.Fil) GAZETTE. [No. 38

1268 THE NEW ZEALA.fil) GAZETTE. [No. 38 MILITARY AREA No'. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-oontinMd. 259042 Dixon, George Frederick, bee-keeper, Argyle St., Mataura. 070928 Fitzpatrick, Owen Peter, electrician's apprentice, Salford St., 244546 Dixon, Ronald Henry, draper's assistant, 162 Leet St., Gore. Invercargill. 398372 Fiveash, William Arthur, sawmiller, Houipapa, Catlins. 239563 Dobbie, James Arnott, farm hand, Menzies Ferry, Southland. 277688 Fleck, William, dairy-farmer, P.O. Box 9, Riverton. 280524 Dobbie, Robert· Douglas, farm assistant, Menzies Ferry, 404906 Fleming; John William, stable hand, care of Todd Bros., Southland. Chemes Lodge, Mataura. 2.50001 Dodd, Gibson Fisher, farm hand, Glenham, Invercargill. 288629 Fleming, William John, labourer, care of Mr. Ian Fraser, '253845 Dodds, Andrew James, farm hand, care of G. McKenzie, Section 4, Wright's Bush Rural Delivery, Southland. Croydon. 417394 Fletcher, Daniel Lochhead, Fairfax, Southland. , 253846 Dodds, Ian Douglas, farm hand, Ferndale Rural Delivery, 293349 Flett, Archibald James Roy, storekeeper, Maclennan, Gore. Southland. 083812 Donald, Alfred Norman, lorry-driver, .Gore-Waikaka Rural 204614 Flynn, Frank, shepherd, Ohai, Southland. Delivery. · . 172615 Fogarty, William John, clerk (N.Z.R.), Balclutha. 294771 Donald, Allan James Clifford, farm hand, Section 5, -Otahuti 373223 Folim, James William, Morton Mains. Rural Delivery, Invercargill. 013791 Folster, William John, law clerk, Oakland St., Mataura. 253843 Donaldson, John Sydney, Avon, Gore. 083748 Forbes, Thomas Grieve, shepherd, Waimumu, Rural De- 244431 Donaldson, Robert John, Section 6, Wrights Bush, Gladfield . livery, Gore. Rural Delivery. 377042 Ford, Maurice Edwin, Waikaka Rural Delivery, Gore. 089846 Donaldson, William Lance, labourer, 173 Tweed St., Inver 292619 Ford, Patrick, shepherd, care of McLeod Bros., Wantwood cargill. -

No 6, 3 February 1955

No. 6 101 NEW ZEALAND THE New Zealand Gazette Published by Authori~ WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 3 FEBRUARY 1955 Land Held for Housing Purposes Set A.part for Purposes Land Held f01· a Public School Set A.part for Road. in Green Incidental to Coal-mining Operations in Block III, Wairio Island Bush Survey District Survey District [L.S.] C. W. M. NORRIE~ Governor-General [L.S.] C. W. M. NORRIE, Governor-General A PROCLAMATION A PROCLAMATION URSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928, I, Lieutenant P General Sir Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie, the URSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928 and section 170 Governor-General of New Zealand, hereby proclaim and declare P of the Coal Mines Act 1925, I, Lieutenant-General Sir that the land described in the Schedule hereto now held for a Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie, the Governor-General of public school is hereby set apart for road; and I also declare New ZeaJand, hereby proclaim and declare that the surface that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after the of the land described in the Schedule hereto, together with 7th day of February 1955. the subsoil above a plane 100 ft. below and approximately parallel to the surface of the said land now held for housing purposes, is hereby set apart for purposes incidental to coal SCHEDULE mining operations; and I also declare that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after the 7th day of February 1955. APPROXIMATE areas of the pieces of land set apart: A. R. P. Being 0 0 3 · 2 Part Section 37. -

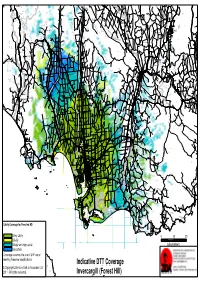

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

The New Zealand Gazette. 883

MAR. 25.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 883 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. 533250 Daumann, Frederick Charles, farm labourer, care of post- 279563 Field, Sydney James, machinist, care of Post-office, Mac office, Lovells Flat. lennan, Catlins. 576554 Davis, Arthur Charles, farm labourer, Dipton. 495725 Field, William Henry, fitter and turner, 36 Princes St. 499495 Davis, Kenneth Henry, freezing worker, Dipton St. 551404 Findlay, Donald Malcolm, cheesemaker, care of Seaward 575914 Davis, Verdun John Lorraine, second-hand dealer, 32 Eye St. Downs Dairy Co., Seaward Downs, Southland. 578471 Dawson, Alan Henry, salesman, 83 Robertson St. 498399 Finn, Arthur Henry, farmer, Wallacetown. 590521 Dawson, John Alfred, rabbiter, care of Len Stewart, Esq., 498400 Finn, Henry George, mill worker, Stewart St., Balclutha. West Plains Rural Delivery. 622455 Fitzpatrick, Matthew Joseph, messenger, Merioneth St., 611279 Dawson, Lewis Alfred, oysterman, 199 Barrow St., Bluff. Arrowtown. 573736 Dawson, Morell Tasman, Jorry-driver, 12 Camden St. 553428 Flack, Charles Albert, labourer, Albion St., Mataura. 591145 Dawson, William Peters, carrier, Pa1merston St., Riverton. 562423 Fleet, Trevor, omnibus-driver, 305 Tweed St. 622362 De La Mare, William Lewis, factory worker, 106 Windsor St. 404475 Flowers, Gord<;m Sydney, labourer, 270 Tweed St. 623417 De Lautour, Peter Arnaud, bank officer, care of Bank of 536899 Forbes, William, farmer, Lochiel Rural Delivery. N.Z., Roxburgh. 492676 Ford, Leo Peter, fibrous-plasterer, 82 Islington St. 490649 Dempster, George Campbell, porter, 24 Oxford St., Gore. 492680 Forde, John Edmond, surfaceman, Maclennan, Catlins. 526266 Dempster, Victor Trumper, grocer, 20 Fulton St. 492681 Forde, John Francis, transport-driver, North Rd., Colling- 493201 Denham, Stuart Clarence, linesman, 81 Pomona St. -

The Soils of Southland and Their Potential Uses E

THE SOILS OF SOUTHLAND AND THEIR POTENTIAL USES E. J. B. CUTLER, Pedologist, Soil Bureau, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Dunedin The pedologist should concern himself not only with mapping and classification of soils; he should examine the use to which soils are put and the changes that take place under varying kinds of use or misuse. The soil survey is only the starting point; it shows the physical, chemical and genetic characteristics of soils, their distribution and relationship to environment. First of all we are interested in the nature of our soils in their undisturbed native state. We can then~ follow the changes that have taken place with changing farming techniques and try to predict desirable changes or modifications; changes which will not only improve the short term production from the soils, but enable us to maintain long-term, sustained-yield production. These prin- ciples apply equally in the mountains and on the plains. Secondly we are interested in seeing that our soil resources arc used most efficiently; that usage of soils takes place in a logical way and that those concerned .with economics are aware of the limitations of the soil as well as of its potentialities. Thirdly there is the aesthetic viewpoint, perhaps not capable of strict scientific treatment but nonetheless a very important one to all of us as civilised people. There is no reason why our landscape should not be planned for pleasure as well as for profit. THE SOILS OF SOUTHLAND The basic soil pattern of Southland is fairly simple; there are three groups of soils delineated primarily by climatic factors. -

Bullinggillianm1991bahons.Pdf (4.414Mb)

THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY PROTECTION OF AUTHOR ’S COPYRIGHT This copy has been supplied by the Library of the University of Otago on the understanding that the following conditions will be observed: 1. To comply with s56 of the Copyright Act 1994 [NZ], this thesis copy must only be used for the purposes of research or private study. 2. The author's permission must be obtained before any material in the thesis is reproduced, unless such reproduction falls within the fair dealing guidelines of the Copyright Act 1994. Due acknowledgement must be made to the author in any citation. 3. No further copies may be made without the permission of the Librarian of the University of Otago. August 2010 Preventable deaths? : the 1918 influenza pandemic in Nightcaps Gillian M Bulling A study submitted for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honours at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. 1991 Created 7/12/2011 GILLIAN BULLING THE 1918 INFLUENZA PANDEMIC IN NIGHTCAPS PREFACE There are several people I would like to thank: for their considerable help and encouragement of this project. Mr MacKay of Wairio and Mrs McDougall of the Otautau Public Library for their help with the research. The staff of the Invercargill Register ofBirths, Deaths and Marriages. David Hartley and Judi Eathorne-Gould for their computing skills. Mrs Dorothy Bulling and Mrs Diane Elder 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures 4 List of illustrations 4 Introduction , 6 Chapter one - Setting the Scene 9 Chapter two - Otautau and Nightcaps - Typical Country Towns? 35 Chapter three - The Victims 53 Conclusion 64 Appendix 66 Bibliography 71 4 TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS Health Department Notices .J q -20 Source - Southland Times November 1918 Influenza Remedies. -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day. -

Proposed Southland District Plan Schedule

Recommending Report: Proposed Southland District Plan Schedule 5.3 - Designations (Excluding Designation 80 - Te Anau Wastewater Treatment Area) Including Recommendations on Notices of Requirement 1. Introduction This report considers submissions and further submissions which were received on Schedule 5.3 which contained an updated list of Designations. This report excludes matters related to Designation 80 - Te Anau Wastewater Treatment Area as this is the matter of a separate hearing process. The report has been prepared in accordance with Section 42A of the Resource Management Act 1991, to assist the Hearing Committee in its deliberations. It is important to note that the staff recommendations outlined in this report do not reflect a decision of the Council. The Hearing Committee is not bound by the recommendations in this report. Following the consideration of all of the submissions and supporting evidence presented at the hearing, a decision report will be prepared outlining the decisions made by the Hearing Committee in respect of each submission and the overall plan. 2. Context for Schedule 5.3 - Designations - Section 5 of the Plan This report considers each requirement (designation) and submissions which were received on Schedule 5.3 - Designations of the Proposed Southland District Plan (excluding Designation D80 - Te Anau Wastewater Treatment Area which is the subject of another hearing process). The report includes a recommendation to the Committee on each requirement (designation) and associated submissions that have been received. Unlike other proposed District Plan hearings the Committee will make recommendations to the requiring authorities on whether to confirm, modify, impose conditions or withdraw each requirement (designation). -

NZ Gazette 1876

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently This sampler file includes the title page and various sample pages from this volume. This file is fully searchable (read search tips page) but is not FASTFIND enabled New Zealand Gazette 1876 Ref. NZ0110-1876 ISBN: 978 1 921315 21 3 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by the University of Queensland Library http://www.library.uq.edu.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

![Fuy 7.] the NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 1271](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9377/fuy-7-the-new-zealand-gazette-1271-1679377.webp)

Fuy 7.] the NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 1271

fuy 7.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 1271 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. 431803 Lindsay, George Edzell, labourer, 77 Bann St., Bluff. 424075 McDowell, Jabez Alexander, excavator-driver and engine. 244440 Lindsay, James Andrew, farmer, Wright's Bush, Glad.field driver, McQuarrie St., Invercargill. Rural Delivery. 060830 McElligott, William Isaac, coal-miner, Ohai, Southland. 236314 Lindsay, Robert Caldwell, P.O. Box 61, Winton. 286087 McElrea, Thomas, wool-presser, care of Mrs. Farguharson, 410905 Little, Earnest Keith, yardman, Progress Valley, Puhanga , Baker St., Stirling. hau Rural Delivery, Invercargill. i 290045 McEntyre, John Francis, farm hand, Arrowtown. 267471 Little, Leslie John Sidey, labourer, 81 Liffey St., Bluff. , 289159 McEwan, Kenneth Gordon, farm.hand, Glenham. 260208 Littlejohn, Ivan Moore, sheep-farmer, Gore-Conical Hills '273006 McFadden, John Alexander, carpenter's apprentice, Thorn- Rural Delivery. ' bury. 408973 Livingstone, .Gordon Stanley, farm hand, Hokonui, South , 244298 McGarvie, Desmond John, farm labourer, Section 6, Otara. land. Rural Delivery. 184785 Lloyd, John Llewellyn, apprentice fitter aud turner, 22 : 398810 McGhee, Frederick John, winch-driver, Nightcaps. Princes St., Invercargill. ! 411348 Macgillivray, Donald Alexander, farm hand, Otapiri Rural 253852 Lochhead, Ross Shearer, sheep-farmer, Kaitangata. , Delivery, Winton, Southland. 433567 Lockett, Reuben Alfred, farmer, Riverton. · 064003 MacGregor, Donald McRae, sheep-farmer, Box 34, Winton. 416950 Lockhart, Brendan Redmond Hanarahan, painter and ; 266369 McGregor, Douglas, farmer, care of Box 23, Balfour. paperhanger, Box 26, Clarksville, Milton. : 230799 McGrouther, William James, carpenter, care of J, F. 277972 Lockhart, Edward ,Joseph, farm labourer, Fairpface Station, ' McGrouther, farmer, Wyndham. Riversdale. '391186 Mcinnes, Frederick, labourer, 5 Dudley St., Waikiwi. -

Invercargill CITY COUNCIL

Invercargill CITY COUNCIL NOTICE OF MEETING Notice is hereby given of the Meeting of the Invercargill City Council to be held in the Council Chamber, First Floor, Civic Administration Building, 101 Esk Street, Invercargill on Tuesday 28 October 2014 at 4.00 pm His Worship the Mayor Mr T R Shadbolt JP Cr DJ Ludlow (Deputy Mayor) CrR LAbbott Cr RR Amundsen Cr KF Arnold Cr N D Boniface Cr A G Dennis Cr I L Esler Cr PW Kett CrG D Lewis Cr I R Pottinger Cr G J Sycamore Cr LS Thomas EIRWEN HARRIS MANAGER, SECRETARIAL SERVICES AGENDA Page 1. APOLOGIES 2. PUBLIC FORUM 2.1 MENTAL HEALTH SYSTEMS IN SOUTHLAND Michelle Bennie will be in attendance to speak to this Item. 2.2 DEVELOPMENT OF A SOUTHLAND HERITAGE STRATEGY Anna Coleman, Consultant for Heritage Southland will be in attendance to speak to this Item. 3. REPORT OF THE INVERCARGILL YOUTH COUNCIL 3.1 YOUTH ANNUAL REPORT 8 Appendix 1 9 3.2 YOUTH COUNCIL LEADERSHIP SURVEY 8 4. MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF COUNCIL HELD ON 11 23 SEPTEMBER 2014 5. MINUTES OF THE EXTRAORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL 19 HELD ON 20 OCTOBER 2014 6. MINUTES OF THE EXTRAORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL HELD ON 21 OCTOBER 2014 To be circulated separately. 7. MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BLUFF COMMUNITY 29 BOARD HELD ON 6 OCTOBER 2014 8. MINUTES OF COMMITTEES 8.1 COMMUNITY SERVICES COMMITTEE 13 OCTOBER 2014 37 8.2 REGULATORY SERVICES COMMITTEE 14 OCTOBER 2014 43 8.3 FINANCE AND POLICY COMMITTEE 21 OCTOBER 2014 To be circulated separately. -

Board of Governors : Chairman: R

Incorporated 1877 Opened 188I Inve reargill l Herbert Street Board of Governors : Chairman: R. M.STRANG, Esq. MRS J. N. ARMOUR. J. T. CARSWELL, Esq. JOHN GILKISON, Esq. F. G. STEVENSON, Esq. HIS WORSHIP THE MAYOR OF INVERCARGILL (John Miller, Esq.) Secretary and Treasurer : MR H. T. THOMPSON, Education Office, Tay Street, Invercargill. Rector: G. H. UTTLEY, M.A., D.Sc. (N.Z.), F.G.S. (London). Assistant Masters : J. L. CAMERON, M.A. A. R. DUNLOP, M.A. H. W. SLATER, M.A. B.Sc. R. D. THOMPSON, M.A., M.Sc. J. S. McGRATH, B.A, A.G. HARRINGTON, M.Sc. A. S. HOGG, M.Sc. A. H. ROBINS, B.A. A. J. DEAKER, M.A. J.C. BRAITHWAITE, :a.A. J. FLANNERY W. S. ALLAN, B.Agr.Sc. (to Oct. 1st). H. DREES, M.A. E. S. HOBSON, B.Sc. (Relieving). Gymnastics : ' Singing: J. PAGE. H. KENNEDY BLACK, F.T.C.L., L.R.S.M. Dancing: ALEX. SUTHERLAND. School Officer R. LEPPER. -� Officers, School 1935.- Editorials PREFECTS: 1935 Retrospect. L. Jones (Head), G. M. Thomson, C. H. Baird, C. W. War�urton, S. Taylor, I. E. Wilson, J. 0. Macpherson, P. E. Hazledme. in LIBRARY: Schools in the British system have come primarily to recognize char M. J. Chaplin (Head Librarian), L. M. �o�·nwell, E. G. F. Furby, P. J. L. McNamara, V. B. de la Perrelle, N. F. G1lk1son, D. W. Crowley, R. D. Fogo. acter development as their most important sphere. We believe that work to have been successfully continued. Our football record has been one of SOUTHLANDIAN: mixed success; cricket, definitely successful, while other outdoor activities The Prefects; Form VI.