Bullinggillianm1991bahons.Pdf (4.414Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Health Care in Rural Southland

"Putting The Bricks In place"; primary Health Care Services in Rural Southland Executive Summary To determine what the challenges are to rural primary health care, and nlake reconlmendations to enhance sustainable service provision. My objective is to qualify the future needs of Community Health Trusts. They must nleet the Ministry of Health directives regarding Primary Healthcare. These are as stated in the back to back contracts between PHOs and inclividual medical practices. I have compiled; from a representative group of rural patients, doctors and other professionals, facts, experiences, opinions and wish lists regarding primary medical services and its impact upon them, now and into the future. The information was collected by survey and interview and these are summarised within the report. During the completion of the report, I have attempted to illustrate the nature of historical delivery of primary healthcare in rural Southland. The present position and the barriers that are imposed on service provision and sustainability I have also highlighted some of the issues regarding expectations of medical service providers and their clients, re funding and manning levels The Goal; "A well educated (re health matters) and healthy population serviced by effective providers". As stated by the Chris Farrelly of the Manaia PHO we must ask ourselves "Am I really concerned by inequalities and injustice? We find that in order to achieve the PHO goals (passed down to the local level) we must have; Additional health practitioners Sustainable funding And sound strategies for future actions through a collaborative model. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PAGE 1 CONTACTS Mark Crawford Westridge 118 Aparima Road RD 1 Otautau 9653 Phone/ fax 032258755 e-mail [email protected] Acknowledgements In compiling the research for this project I would like to thank all the members of the conlmunity, health professionals and committee members who have generously given their time and shared their knowledge. -

No 6, 3 February 1955

No. 6 101 NEW ZEALAND THE New Zealand Gazette Published by Authori~ WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 3 FEBRUARY 1955 Land Held for Housing Purposes Set A.part for Purposes Land Held f01· a Public School Set A.part for Road. in Green Incidental to Coal-mining Operations in Block III, Wairio Island Bush Survey District Survey District [L.S.] C. W. M. NORRIE~ Governor-General [L.S.] C. W. M. NORRIE, Governor-General A PROCLAMATION A PROCLAMATION URSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928, I, Lieutenant P General Sir Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie, the URSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928 and section 170 Governor-General of New Zealand, hereby proclaim and declare P of the Coal Mines Act 1925, I, Lieutenant-General Sir that the land described in the Schedule hereto now held for a Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie, the Governor-General of public school is hereby set apart for road; and I also declare New ZeaJand, hereby proclaim and declare that the surface that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after the of the land described in the Schedule hereto, together with 7th day of February 1955. the subsoil above a plane 100 ft. below and approximately parallel to the surface of the said land now held for housing purposes, is hereby set apart for purposes incidental to coal SCHEDULE mining operations; and I also declare that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after the 7th day of February 1955. APPROXIMATE areas of the pieces of land set apart: A. R. P. Being 0 0 3 · 2 Part Section 37. -

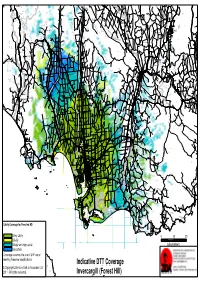

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

The New Zealand Gazette. 331

JAN. 20.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 331 MILITARY AREA No, 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No.· 12 (INVERCARGILL)-oontinued. 499820 Irwin, Robert William Hunter, mail-contractor, Riversdale, 532403 Kindley, Arthur William,·farm labourer, Winton. Southland. 617773 King, Duncan McEwan, farm hand, South Hillend Rural 598228 Irwin, Samuel David, farmer, Winton, Otapiri Rural Delivery, Winton. Delivery, Brown. 498833 King, Robert Park, farmer, Orepuki, Rural Delivery, 513577 Isaacs, Jack, school-teacher, The School, Te Anau. Riverton-Tuatapere. 497217 Jack, Alexander, labourer, James St., Balclutha. 571988 King, Ronald H. M., farmer, Orawia. 526047 Jackson, Albert Ernest;plumber, care of R. G. Speirs, Ltd., 532584 King, Thomas James, cutter, Rosebank, Balclutha. Dee St., Invercargill. 532337 King, Tom Robert, agricultural contractor, Drummond. 595869 James, Francis William, sheep,farmer, Otautau. 595529 Kingdon, Arthur Nehemiah, farmer, Waikaka Rural De. 549289 James, Frederick Helmar, farmer, Bainfield Rd., Waiki.wi livery, Gore. West Plains Rural Delivery, Inveroargill, 595611 Kirby, Owen Joseph, farmer, Cardigan, Wyndham. 496705 James, Norman Thompson, farmer, Otautau, Aparima 571353 Kirk, Patrick Henry, farmer, Tokanui, Southland. Rural Delivery, Southland. 482649 Kitto, Morris Edward, blacksmith, Roxburgh. 561654 Jamieson, Thomas Wilson, farmer, Waiwera South. 594698 Kitto, Raymond Gordon, school-teacher, 5 Anzac St., Gore. 581971 Jardine, Dickson Glendinning, sheep-farmer, Kawarau Falls 509719 Knewstubb, Stanley Tyler, orchardist, Coal Creek Flat, Station, Queenstown. Roxburgh. , 580294 Jeffrey, Thomas Noel, farmer, Wendonside Rural Delivery, 430969 Knight, David Eric Sinclair, tallow assistant, Selbourne St. Gore. Mataura. 582520 Jenkins, Colin Hendry, farm manager, Rural Delivery, 467306 Knight, John Havelock, farmer, Riverton, Rural Delivery, · Balclutha. Tuatapere. 580256 Jenkins, John Edward, storeman - timekeeper, Homer 466864 Knight, Ralph Condie, civil servant, 83 Ohara St., Inver. -

Waste Options in Rural Southland

Waste Options in Rural Southland armers have always been great at giving new life to old materials, but there is plenty Fmore that can be done to improve waste management on the farm. Southland has a variety of waste facilities ranging from recycling centres where people freely drop off recyclables to waste transfer stations that accept household and commercial rubbish. Rural Refuse Collection Rural properties have several options for rubbish collection. Private contractors that offer collection services are listed in the yellow pages under ‘Waste Disposal’ and ‘Recycling’. However it could be just as easy to take your rubbish/recycling to the nearest transfer station, or recycling to your local recycling centre. Waste Transfer Stations Waste Transfers Stations are for the disposal of rubbish, greenwaste (garden waste), scrap metal recyclables, pre-loved materials and small quantities of hazardous chemicals. Some fees do apply. • Lumsden Transfer Station, 35 Oxford Street, Lumsden • Otautau Transfer Station, 5 Bridport Road, Otautau • Riverton Transfer Station, 1 Havelock Street, Riverton • Gore Transfer Station, Toronto Street, Gore • Invercargill Waste Transfer Station, 303 Bond Street, Invercargill • Bluff Transfer Station, 75 Suir Street, Bluff • Wyndale Transfer Station, 190 Edendale Wyndham Road, Edendale • Winton Transfer Station, 193 Florence Road, Winton • Te Anau Transfer Station, Te Anau Manapouri Highway, Te Anau Recycle Drop-off Centre There are recycle drop-off centres located throughout the district for household recyclables. -

Consequences to Threatened Plants and Insects of Fragmentation of Southland Floodplain Forests

Consequences to threatened plants and insects of fragmentation of Southland floodplain forests S. Walker, G.M. Rogers, W.G. Lee, B. Rance, D. Ward, C. Rufaut, A. Conn, N. Simpson, G. Hall, and M-C. Larivière SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 265 Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10–420 Wellington, New Zealand Cover: The Dean Burn: the largest tracts of floodplain forest ecosystem remaining on private land in Southland, New Zealand. (See Appendix 1 for more details.) Photo: Geoff Rogers, RD&I, DOC. Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science and Research. © Copyright April 2006, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 ISBN 0–478–14070–3 This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing by Geoff Gregory and layout by Ian Mackenzie. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS -

The New Zealand Gazette 1489

5 ,SEPTEMBER THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1489 Allenton- Onetangi, Community Hall. Creek Road Hall. Ostend, First Aid Room. School. Palm Beach, Domain Hall. Anama School. Rocky Bay, Omiha Hall. Arundel School. Surfdale, Surfdale Hall. Ashburton- Borough Chambers. College, Junior Division, Cameron Street. College, Senior DiviSIon, Cass Street. Courthouse. Hampstead School, Wellington Street. Burkes Pass Public Hall. Avon Electoral District Carew School. Aranui- Cave Public Hall. Public School, Breezes Road. Chamberlain (Albury), Coal Mine Road Comer, Mr M. A. St. James School, Rowan Avenue. Fraser's House. Bromley Public School. Clandeboye School. Burwood- Coldstream, Mr Studholmes Whare. Brethren Sunday School, Bassett Street. Cricklewood Public Hall. Cresswell Motors Garage, New Brighton Road. Ealing Public Hall. Public School, New Brighton Road. Eiffelton SchooL Dallington Anglican Sunday School, Gayhurst Road. Fairlie Courthouse. Linwood North Public School, Woodham Road. Flemington SchooL New Brighton- Gapes Valley Public Hall. Central School, Seaview Road. Geraldine- Freeville Public School, Sandy Avenue. Borough Chambers. Garage, corner Union and Rodney Streets. Variety Trading Co., Talbot Street. North Beach Methodist Church Hall, Marriotts Road. Greenstreet Hall. North New Brighton- Hermitage, Mount Cook, Wakefield Cottage. Peace Memorial Hall, Marine Parade. Hilton SchooL Public School, Leaver Terrace. Hinds SchooL Sandilands Garage, 9 Coulter Street. Kakahu Bush Public Hall. Shirley- Kimbell Old School Building. Garage, 40 Vardon Crescent. Lake Pukaki SchooL Public School, Banks Avenue. Lismore SchooL Rowe Memorial Hall, North Parade. Lowc1iffe SchooL South New Brighton- Maronan Road Hall. Garage, 1 Caspian Street. Mayfield School. Public School, Estuary Road. Milford School. Wainoni- Montalto SchooL Avondale Primary School, Breezes Road. Mount Nessing (Albury) Public Hall. -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day. -

Southland Trail Notes Contents

22 October 2020 Southland trail notes Contents • Mararoa River Track • Tākitimu Track • Birchwood to Merrivale • Longwood Forest Track • Long Hilly Track • Tīhaka Beach Track • Oreti Beach Track • Invercargill to Bluff Mararoa River Track Route Trampers continuing on from the Mavora Walkway can walk south down and around the North Mavora Lake shore to the swingbridge across the Mararoa River at the lake’s outlet. From here the track is marked and sign-posted. It stays west of but proximate to the Mararoa River and then South Mavora Lake to this lake’s outlet where another swingbridge provides an alternative access point from Mavora Lakes Road. Beyond this swingbridge, the track continues down the true right side of the Mararoa River to a third and final swing bridge. Along the way a careful assessment is required: if the Mararoa River can be forded safely then Te Araroa Trampers can continue down the track on the true right side to the Kiwi Burn then either divert 1.5km to the Kiwi Burn Hut, or ford the Mararoa River and continue south on the true left bank. If the Mararoa is not fordable then Te Araroa trampers must cross the final swingbridge. Trampers can then continue down the true left bank on the riverside of the fence and, after 3km, rejoin the Te Araroa opposite the Kiwi Burn confluence. 1 Below the Kiwi Burn confluence, Te Araroa is marked with poles down the Mararoa’s true left bank. This is on the riverside of the fence all the way down to Wash Creek, some 16km distant. -

Dan Davin Re-Visited

40 Roads Around Home: Dan Davin Re-visited Denis Lenihan ‘And isn’t history art?’ ‘An inferior form of fiction.’ Dan Davin: The Sullen Bell, p 112 In 1996, Oxford University Press published Keith Ovenden’s A Fighting Withdrawal: The Life of Dan Davin, Writer, Soldier, Publisher. It is a substantial work of nearly 500 pages, including five pages of acknowledgements and 52 pages of notes, and was nearly four years in the making. In the preface, Ovenden makes the somewhat startling admission that ‘I believed I knew [Davin] well’ but after completing the research for the book ‘I discovered that I had not really known him at all, and that the figure whose life I can now document and describe in great detail remains baffingly remote’. In a separate piece, I hope to try and show why Ovenden found Davin retreating into the distance. Here I am more concerned with the bricks and mortar rather than the finished structure. Despite the considerable numbers of people to whom Ovenden spoke about Davin, and the wealth of written material from which he quotes, there is a good deal of evidence in the book that Ovenden has an imperfect grasp of many matters of fact, particularly about Davin’s early years until he left New Zealand for Oxford in 1936. The earliest of these is the detail of Davin’s birth. According to Ovenden, Davin ‘was born in his parents’ bed at Makarewa on Monday 1 September 1913’. Davin’s own entry in the 1956 New Zealand Who’s Who records that he was born in Invercargill. -

Proposed Southland District Plan Schedule

Recommending Report: Proposed Southland District Plan Schedule 5.3 - Designations (Excluding Designation 80 - Te Anau Wastewater Treatment Area) Including Recommendations on Notices of Requirement 1. Introduction This report considers submissions and further submissions which were received on Schedule 5.3 which contained an updated list of Designations. This report excludes matters related to Designation 80 - Te Anau Wastewater Treatment Area as this is the matter of a separate hearing process. The report has been prepared in accordance with Section 42A of the Resource Management Act 1991, to assist the Hearing Committee in its deliberations. It is important to note that the staff recommendations outlined in this report do not reflect a decision of the Council. The Hearing Committee is not bound by the recommendations in this report. Following the consideration of all of the submissions and supporting evidence presented at the hearing, a decision report will be prepared outlining the decisions made by the Hearing Committee in respect of each submission and the overall plan. 2. Context for Schedule 5.3 - Designations - Section 5 of the Plan This report considers each requirement (designation) and submissions which were received on Schedule 5.3 - Designations of the Proposed Southland District Plan (excluding Designation D80 - Te Anau Wastewater Treatment Area which is the subject of another hearing process). The report includes a recommendation to the Committee on each requirement (designation) and associated submissions that have been received. Unlike other proposed District Plan hearings the Committee will make recommendations to the requiring authorities on whether to confirm, modify, impose conditions or withdraw each requirement (designation). -

THE NEW ZEALAND ·GAZETTE. [No

2728 THE NEW ZEALAND ·GAZETTE. [No. 99 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-con.tinued. MJLITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)...;_contiooed. 511872 Shieffelbein, Henry, meat-company employee, Burns 513238 Stout, Eric, bank-,officer, 51 Fulton St. St., Mataura. 495211 Stronach, James, fisherman, Niagara, Invercargill 612369 Shieffelbien, Norman Rudolf, hauler-driver, Fortifica- Waikawa R.D. tion P.B., Waimahaka. 543301 Stuart, · Alexander, farmer, Otaitai Bush, Riverton 552160 Shirley, · Raymond Fraser Reid, line-ganger1 Ward St. R.D. 512564 Shirreffs, Arthur Hay, plumber, 166 Nelson St. 495221 Stuart, Alexander, instructor in agriculture,· 158 Lewis 578666 Shore, Ernest Wingate Clarence, lorry-driver, 23 St. · Dudley St. 541786 Stuart, Leslie Watt, farmer-, Riverton R.D. 581921 Siddall, William .T oseph Alfred, dry-cleaner and dyer, 594436 Sturgess, Arthur James, sawmill-manager, Orawia. 17 Conon St. 631892 Styles, Charles Thomas, farm hand, Wendon Valley 545856 Sime, Robert Spence, sawmiller, Tapanui. · R.D., Waikaka. 588213 Simmers, George Archibald, farmer, Waikoikoi, Gore 515054 Summerell, ·wmiam Caleb Samson, omnibus-driver, Conical Hill R.D. Palmerston St., Riverton. 494554 Simpson, Douglas, school-teacher, schoolhouse, Lochiel. 541426 Summers,, John Brown, shepherd, ,: Threepwood," R.D., !580986 Simpson, James, music-teacher, 11 Mary St. Queenstown. 541767 Simpson, William Thomas, farmer, Waikaka. 536106 Sutherland, Alistair Knud, engineer,. 65 Elizabeth St. 541762 Sinclair, ".Edward, poultry-farmer, Bain St. 589602 Sutherland, Norman John Charles, master grocer, 494538 Sinclair, James Alfred, freezing-works 1:l.and, 245 325 Ness St. Crinan St. 496248 Sutherland Robert Ewen, clerk, 11 Crewe St;, Gore. 471656 Sinclair, ~Tohn, farmer, Section 3, Otara R.D. 558125 Sutherland; Vemon Ha:r:old Wilfred, sawmiller, Mac- 471657 Sinclair, John Donald, builder, Jolmston Rd., Night Lennon, Chaslands.