The Soils of Southland and Their Potential Uses E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Conversation with the Mayor Gary Tong

1 IN CONVERSATION WITH THE MAYOR GARY TONG through new technology (such as through our roading team’s use of drones). On a personal note, two things have stood have out this year; one of great sadness, the other a highlight. Sadly, we farewelled former Mayor Frana Cardno in April. She was a great role model and the reason I got into politics; a wonderful woman who will be sadly missed. Rest in peace, Frana. At the other end of the spectrum, in May I helped host His Mayor Gary Tong Royal Highness Prince Harry’s visit to Stewart Island. He’s a top bloke whose visit generated fantastic publicity for the Much like before crossing the road, island and Southland District. I’m sure our tourism industry at the end of each year I like to will see the benefi ts for some while yet. pause and look both ways. Just a few months ago the Southland Regional Development Strategy was launched. It gives direction for development of the region as a whole, with the primary focus on increasing our population. It tells us focusing on population growth will There’s a lot to look back on in 2015, and mean not only more people, it will provide economic growth, there’s plenty to come in 2016. Refl ecting on skilled workers, a better lifestyle, and improved health, the year that’s been, I realise just how much education and social services. We need to work together has happened in Southland District over the to achieve this; not just councils, but business, community, past year. -

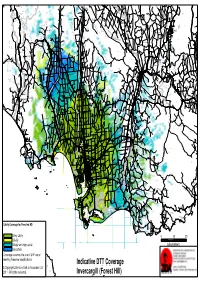

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

The New Zealand Gazette. 883

MAR. 25.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 883 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. 533250 Daumann, Frederick Charles, farm labourer, care of post- 279563 Field, Sydney James, machinist, care of Post-office, Mac office, Lovells Flat. lennan, Catlins. 576554 Davis, Arthur Charles, farm labourer, Dipton. 495725 Field, William Henry, fitter and turner, 36 Princes St. 499495 Davis, Kenneth Henry, freezing worker, Dipton St. 551404 Findlay, Donald Malcolm, cheesemaker, care of Seaward 575914 Davis, Verdun John Lorraine, second-hand dealer, 32 Eye St. Downs Dairy Co., Seaward Downs, Southland. 578471 Dawson, Alan Henry, salesman, 83 Robertson St. 498399 Finn, Arthur Henry, farmer, Wallacetown. 590521 Dawson, John Alfred, rabbiter, care of Len Stewart, Esq., 498400 Finn, Henry George, mill worker, Stewart St., Balclutha. West Plains Rural Delivery. 622455 Fitzpatrick, Matthew Joseph, messenger, Merioneth St., 611279 Dawson, Lewis Alfred, oysterman, 199 Barrow St., Bluff. Arrowtown. 573736 Dawson, Morell Tasman, Jorry-driver, 12 Camden St. 553428 Flack, Charles Albert, labourer, Albion St., Mataura. 591145 Dawson, William Peters, carrier, Pa1merston St., Riverton. 562423 Fleet, Trevor, omnibus-driver, 305 Tweed St. 622362 De La Mare, William Lewis, factory worker, 106 Windsor St. 404475 Flowers, Gord<;m Sydney, labourer, 270 Tweed St. 623417 De Lautour, Peter Arnaud, bank officer, care of Bank of 536899 Forbes, William, farmer, Lochiel Rural Delivery. N.Z., Roxburgh. 492676 Ford, Leo Peter, fibrous-plasterer, 82 Islington St. 490649 Dempster, George Campbell, porter, 24 Oxford St., Gore. 492680 Forde, John Edmond, surfaceman, Maclennan, Catlins. 526266 Dempster, Victor Trumper, grocer, 20 Fulton St. 492681 Forde, John Francis, transport-driver, North Rd., Colling- 493201 Denham, Stuart Clarence, linesman, 81 Pomona St. -

Southland Centre

SOUTHLAND CENTRE President: Brian Sparrow 165 Davidson Road West, R D 2, Gore 9772 Cellphone 027 490 7770 Email : [email protected] Secretary: Maria Hurrell Southland Sheep Dog Trial Association P O Box 86, Gore 9740 Phone 03 207 1749 Cellphone 027 202 3358 Email : [email protected] Home Address : 464 Craigie Road, R D 1, Gore 9771 Stud Register : Ross Hurrell 464 Craigie Road, R D 1, Gore 9771 Phone 03 207 1749 Cellphone 027 489 9830 Email: [email protected] Promotions Officer: Anna Sparrow 165 Davidson Road West, R D 2, Gore 9772 Cellphone 027 590 7770 Email: [email protected] Archives Officer: Maria Hurrell 464 Craigie Road, R D 1, Gore 9771 Phone 03 207 1749 or 027 202 3358 Email: [email protected] Club Judges Rod Coulter 112 Centre Bush Otapiri Road, R D 2, Winton 9782 Co-ordinator: Phone 03 236 0752 Cellphone 027 283 4570 Email: [email protected] February Waiau CC Penny MacPherson 5th Grounds: Richard & Trudy 2030 Clifden Blackmount Road, R D 2, Otautau 9682 Slee’s Property, Wairaki Phone 03 225 8690 or 027 405 7500 Station, 2030 Clifden Email: [email protected] Blackmount Road Entries Close at 12 Noon February Waimahaka CC Jared Ellis 6th Grounds: Russell & Roslyn 216 Waimahaka-Fortification Road, R D 1, Wyndham 9891 Cook’s Property, 452 Phone 027 284 1401 Waimahaka-Fortification Road Email: [email protected] Entries Close at 12 noon February Wyndham SDTC Marcia Kenndy 12 th & 13 th Grounds: Tim Story’s Property, 934 Wairikiki – Mimihau Road, R D 2, Wyndham 9892 Jedburgh Station, -

II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· ------~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I

Date Printed: 04/22/2009 JTS Box Number: 1FES 67 Tab Number: 123 Document Title: Your Guide to Voting in the 1996 General Election Document Date: 1996 Document Country: New Zealand Document Language: English 1FES 10: CE01221 E II~I6 866 ~II~II~II C - -- ~,~,- - --:- -- - 11 I E14c I· --- ---~--.~~ ~ ---~~ -- ~-~~~ = 'I 1 : l!lG,IJfi~;m~ I 1 I II I 'DURGUIDE : . !I TOVOTING ! "'I IN l'HE 1998 .. i1, , i II 1 GENERAl, - iI - !! ... ... '. ..' I: IElJIECTlON II I i i ! !: !I 11 II !i Authorised by the Chief Electoral Officer, Ministry of Justice, Wellington 1 ,, __ ~ __ -=-==_.=_~~~~ --=----==-=-_ Ji Know your Electorate and General Electoral Districts , North Island • • Hamilton East Hamilton West -----\i}::::::::::!c.4J Taranaki-King Country No,", Every tffort Iws b«n mude co etlSull' tilt' accuracy of pr'rty iiI{ C<llldidate., (pases 10-13) alld rlec/oralt' pollillg piau locations (past's 14-38). CarloJmpllr by Tt'rmlilJk NZ Ltd. Crown Copyr(~"t Reserved. 2 Polling booths are open from gam your nearest Polling Place ~Okernu Maori Electoral Districts ~ lil1qpCli1~~ Ilfhtg II! ili em g} !i'1l!:[jDCli1&:!m1Ib ~ lDIID~ nfhliuli ili im {) 6m !.I:l:qjxDJGmll~ ~(kD~ Te Tai Tonga Gl (Indudes South Island. Gl IIlllx!I:i!I (kD ~ Chatham Islands and Stewart Island) G\ 1D!m'llD~- ill Il".ilmlIllltJu:t!ml amOOvm!m~ Q) .mm:ro 00iTIP West Coast lID ~!Ytn:l -Tasman Kaikoura 00 ~~',!!61'1 W 1\<t!funn General Electoral Districts -----------IEl fl!rIJlmmD South Island l1:ilwWj'@ Dunedin m No,," &FJ 'lb'iJrfl'llil:rtlJD __ Clutha-Southland ------- ---~--- to 7pm on Saturday-12 October 1996 3 ELECTl~NS Everything you need to know to _.""iii·lli,n_iU"· , This guide to voting contains everything For more information you need to know about how to have your call tollfree on say on polling day. -

Dan Davin Re-Visited

40 Roads Around Home: Dan Davin Re-visited Denis Lenihan ‘And isn’t history art?’ ‘An inferior form of fiction.’ Dan Davin: The Sullen Bell, p 112 In 1996, Oxford University Press published Keith Ovenden’s A Fighting Withdrawal: The Life of Dan Davin, Writer, Soldier, Publisher. It is a substantial work of nearly 500 pages, including five pages of acknowledgements and 52 pages of notes, and was nearly four years in the making. In the preface, Ovenden makes the somewhat startling admission that ‘I believed I knew [Davin] well’ but after completing the research for the book ‘I discovered that I had not really known him at all, and that the figure whose life I can now document and describe in great detail remains baffingly remote’. In a separate piece, I hope to try and show why Ovenden found Davin retreating into the distance. Here I am more concerned with the bricks and mortar rather than the finished structure. Despite the considerable numbers of people to whom Ovenden spoke about Davin, and the wealth of written material from which he quotes, there is a good deal of evidence in the book that Ovenden has an imperfect grasp of many matters of fact, particularly about Davin’s early years until he left New Zealand for Oxford in 1936. The earliest of these is the detail of Davin’s birth. According to Ovenden, Davin ‘was born in his parents’ bed at Makarewa on Monday 1 September 1913’. Davin’s own entry in the 1956 New Zealand Who’s Who records that he was born in Invercargill. -

Short Walks 2 up April 11

a selection of Southland s short walks contents pg For the location of each walk see the centre page map on page 17 and 18. Introduction 1 Information 2 Track Symbols 3 1 Mavora Lakes 5 2 Piano Flat 6 3 Glenure Allan Reserve 7 4 Waikaka Way Walkway 8 5 Croydon Bush, Dolamore Park Scenic Reserves 9,10 6 Dunsdale Reserve 11 7 Forest Hill Scenic Reserve 12 8 Kamahi/Edendale Scenic Reserve 13 9 Seaward Downs Scenic Reserve 13 10 Kingswood Bush Scenic Reserve 14 11 Borland Nature Walk 14 12 Tuatapere Scenic Reserve 15 13 Alex McKenzie Park and Arboretum 15 14 Roundhill 16 Location of walks map 17,18 15 Mores Scenic Reserve 19,20 16 Taramea Bay Walkway 20 17 Sandy Point Domain 21-23 18 Invercargill Estuary Walkway 24 19 Invercargill Parks & Gardens 25 20 Greenpoint Reserve 26 21 Bluff Hill/Motupohue 27,28 22 Waituna Viewing Shelter 29 23 Waipapa Point 30 24 Waipohatu Recreation Area 31 25 Slope Point 32 26 Waikawa 32 27 Curio Bay 33 Wildlife viewing 34 Walks further afield 35 For more information 36 introduction to short Southland s walking tracks short walks Short walking tracks combine healthy exercise with the enjoyment of beautiful places. They take between 15 minutes and 4 hours to complete Southland is renowned for challenging tracks that are generally well formed and maintained venture into wild and rugged landscapes. Yet many of can be walked in sensible leisure footwear the region's most attractive places can be enjoyed in a are usually accessible throughout the year more leisurely way – without the need for tramping boots are suitable for most ages and fitness levels or heavy packs. -

Envirosouth June 2012 Environment Southland News

Brucie’snow Buddies includes bulletin see page 15 Envirosouth June 2012 Environment Southland News Issue RPS released for submissions Environment Award nominees 27 Funding helps to control pests Floodwarning: 64 years of service From the Chair y the time you read this, our this year. The last time we adopted BCouncillors will be about to a 10-year plan we received over 200 consider 148 submissions on our submissions, so 148 could suggest a Draft Long-term Plan. decline in interest, given we distributed over 40,000 copies of the summary to There are some constant themes – residents and ratepayers. Or it could widespread support for our proposal mean that most people support what to make improved water quality our we’re proposing, and don’t feel the need top priority; both support for and to put pen to paper. Either way, it’s been opposition to the proposal to increase a huge job to prepare programmes the dairy differential rate; extensive and budgets for the first three years support for the proposal to create a of the Long-term Plan, involving long new walkway at Titiroa and a mixed hours for staff and several workshops bag of views on whether we should put for Councillors. The current requirement some money into the rebuild of Stadium to plan in such detail for three years Chairman Ali Timms. Southland to enable it to be used as an can probably be justified but having to emergency facility for civil defence. project the requirements and budgets Ali Timms There were also some submissions that over a further seven years seems an Chairman came out of left field, such as the 29 unnecessary burden. -

![May 7.] the New Zealand Gazette. 1275](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5656/may-7-the-new-zealand-gazette-1275-1855656.webp)

May 7.] the New Zealand Gazette. 1275

MAY 7.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 1275 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continwed. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-oontinwed. 406247 Sparke, Richard James, grader-driver, Wallacetown. 294752 Tayles, Jack, labourer, No. 1 Dome St., Heidelberg, Inver. 391308 Spittle, Frederick James, farmer, Waikoikoi Rural Delivery, cargill. Gore. 239574 Taylor, Eric, farmer, Hartwood, Otautau Rural Delivery. 405515 Spittle, Gordon Henry, labourer, Waikoikoi, Gore-Conical 266824 Taylor, Eric Leslie, labourer, Stobo St., Invercargill. Hills Rural Delivery. 042983 Taylor, Frank Joseph, farmer, Table Hill, Milton. 298367 Stalker, Charles Gilbert (jun.), shearer, Ermedale-Riverton 433113 Taylor, Linton, tractor-driver, Wairakai Valley, Ohai. Rural Delivery. 231055 Taylor, Richard Samuel, farmer, Mokotua, Section 7, 292483 Stanley, Arthur, gorse-grubber, South Riverton. Otara Rural Delivery. 404035 Staunton, John Francis, winch-driver, care of P.O. Box 90, 264304 Taylor, William, storeman, Union St., Milton. Ohai, Southland. 433168 Te.Au, Thomas Henry, labourer, Colao Bay, Riverton. 062956 Stead, Hugh Girvan, 118 Conon St., Invercargill. 427806 Tecofsky, John Thomas, farmer, Pahia. 257784 Steans, Harold Geoffrey, farm hand, care of N. M. McPhail, 409711 Telfer, Hector John, farm hand, Mataura Island. Gore-Benio Rural Delivery. 433432 Tempelton, John Herbert, sawmill hand, care of C. GofJdall, 428742 Stenton, Walter Mervyn, labourer, North Makarewa, South Lumsden. land. 287186 Templeton, Thomas, Fortifipation, via Waimahaka, South 262233 Stephen, John Brown, labourer, 84 Bowmont St., Invercar- land. gill. 297334 Templeton, Thomas David, farm labourer, Pembroke. 253815 Stephenson, John, waggon-trimmer, Dartmouth St., Kai tangata. 267020 Teviotdale, David, farm hand, Wright's Bush, Gladfield 161931 Stevens, Albert Alexander, confectioner, 105 Ettrick St., Rural Delivery. Invercargill. 422654 Thom, John Alexander, hardware salesman, 314 Ettrick St., 276781 Stevens, John Hector, farmer, Balfour, Glenure Rural Invercargill. -

TBE Ntw Zeat.JAND GAZETTE. 3467

·SEPT. 3.J TBE NtW ZEAt.JAND GAZETTE. 3467 *630711, Andrews, William James, Farmer, Eyre Creek, Lumsden. 63154 Burke, Thomas, Bushman, Orepuki, Walla.ce. 63079 Armstrong, Ralph, Farmer, Wyndham. 63155 Burns, William Samuel Henry, Ploughman, Kenningtoll. (13080 Ashton, Robert Cramond, Farm Labourer, Lochiel. 63156 Burt, George, Mail Contractor, Wright's Bush, Southla.nd. 63081 Aspray, George, Tailor, Avenal, Invercargill. 63157 Bushnell, DaHus, Engine:driver, Asher's Siding, Gorge Rd, *63082 Atkinson, Ebenezer Forster, Farmer, 49 Shetla.nd Ht, Kai- Southland. korai, Dunedin. "63158 Butcl, John, Farmer, Arrowtown. 6:~()11:~ Atley, Alfonsis, Farmer, Arthur's Point. 63159 Butler, Victor Leslie, Grocer's Assi8tant, care of Thoma, *63084 Ayson, Ernest Edwin, Farmer, P.O. Box :1, Waikaka. Watt. Storekeeper, Kemrington. *63085 Bain, William Couttfo, Gardener, 14 Princess St, Nort,h (;3162 Caird, Leslie, Flax-miller, Wyndham, Dum'din. Invercargill. 63163 Calder, Alexander Officer. Farmer, Oreti. 63()86 Bainett, Willia.m Eli, Sawmill Employee, Colac, Wallace. 6:1164 Callaghan, John Victor,' Slaughterman, 2:1 Buwmunt Ht" 63088 Baird, Arthur David, Farmer, Myross Bush, Soutbland. Enwood, InvercargilL *63089 Baldwin, Thomas, Bla.eksmith, Drummond. 6:U65 Callender, Percy Miller, ,Farmer, Wekaburri, Lilbmn, Clif- 63()9() Ballantine, Andrew, Publican, Kauana, Southland. den. *63092 Balloch, Duncan Alexander McGregor, Farm Hand, Main 63166 Calvert, James Charles, Farmer, Myross Bush, via Inver- St, Mataura. cargill. 63093 Barclay, Matthew, Railway Employee, Edendale, Southland. 63167 Campbell, Alfred Duncan, Builder, FortrosIl, Southland. 63()94 Barlow, Frank, Carpenter, 155 Dee St, Inverca.rgill. 63168 Campbell, Angus, Farmer, Wyndham, Southland. 63095 Barry, Henry William, Carter, Dublin St, Invereargill. 1)3169 Campbell, Malcolm, Ploughman, Arrowtown, Otago. -

Southland Conservancy

A Directory of Wetlands in New Zealand SOUTHLAND CONSERVANCY Te Anau Basin Wetland Complex (71) Location: 45o27'S, 167o46'E. To the east and southeast of Lake Te Anau, Southland, South Island. Area: c.2,400 ha. Altitude: 180-360 m. Overview: The Te Anau Basin Wetland Complex consists of seven distinct and isolated wetlands within the Te Anau Basin. These sites are the Dome Mire and Dismal Swamp area, Kepler Mire, Amoeboid Mire, Kakapo Swamp, Dunton Bog and two areas within the Snowdon Forest. The Dome Mire and Dismal Swamp area and Kepler Mire are described in greater detail as Sites 71a and 71b, respectively. All of the wetlands have a similar glacial origin; however, individual sites vary as a consequence of their history, drainage (water table, amounts of ponded water), fertility, topography etc. The complex of peatlands contains a rich variety of plant communities which include several significant plant distributions and provide important habitat for wildlife. Physical features: The Te Anau Basin lies on the eastern margin of Fiordland, a gneiss/schist/granite massif uplifted by the Alpine Fault on its western margin and carved by extensive glaciation through the Quaternary. On its eastern flank, down-faulting in the Te Anau Basin area has contributed to the preservation of soft Tertiary sedimentary rocks, and the deposition of glacial gravels. During the last glaciation, glaciers occupied much of the basin. Depressions and areas of limited drainage developed in the moraines, tills and outwash gravels as the glaciers retreated. Wetlands have developed on these glacial outwash deposits of last glacial to post-glacial age. -

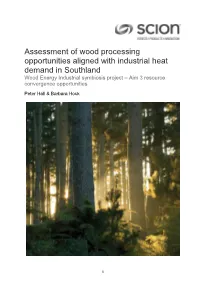

Generic Public Client Report

Assessment of wood processing opportunities aligned with industrial heat demand in Southland Wood Energy Industrial symbiosis project – Aim 3 resource convergence opportunities Peter Hall & Barbara Hock (i) Report information sheet Report title Assessment of wood processing opportunities aligned with industrial heat demand in Southland Authors Peter Hall & Barbara Hock Scion Client MBIE MBIE contract PROP-37659-EMTR-FRI number SIDNEY output 60405 number ISBN Number Signed off by Paul Bennett Date March 2018 Confidentiality Confidential (for client use only) requirement Intellectual © New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited. All rights reserved. Unless property permitted by contract or law, no part of this work may be reproduced, stored or copied in any form or by any means without the express permission of the New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited (trading as Scion). Disclaimer The information and opinions provided in the Report have been prepared for the Client and its specified purposes. Accordingly, any person other than the Client uses the information and opinions in this report entirely at its own risk. The Report has been provided in good faith and on the basis that reasonable endeavours have been made to be accurate and not misleading and to exercise reasonable care, skill and judgment in providing such information and opinions. Neither Scion, nor any of its employees, officers, contractors, agents or other persons acting on its behalf or under its control accepts any responsibility or liability in respect of any information or opinions provided in this Report. Published by: Scion, 49 Sala Street, Private Bag 3020, Rotorua 3046, New Zealand. www.scionresearch.com 2 Executive summary This report presents analyses of the current and projected wood resource and wood processing along with existing heat demand in Southland and Clutha with the aim of identifying wood energy industrial symbiosis opportunities.