FROM POTHOLES to POLICY: How Invercargill City Council Informs Itself Of, and Has Regard To, the Views of All of Its Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE February 2017

AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE February 2017 ABOUT THE NEW ZEALAND AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION 2 FOREWORD 3 PART A: AIRPORT MASTER PLAN GUIDE 5 1 INTRODUCTION 6 2 IMPORTANCE OF AIRPORTS 7 3 PURPOSE OF AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING 9 4 REFERENCE DOCUMENTS 13 5 BASIC PLANNING PROCESS 15 6 REGULATORY AND POLICY CONTEXT 20 7 CRITICAL AIRPORT PLANNING PARAMETERS 27 8 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION AND ENGAGEMENT 46 9 KEY ELEMENTS OF THE PLAN 50 10 CONCLUSION 56 PART B: AIRPORT MASTER PLAN TEMPLATE 57 1 INTRODUCTION 58 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION 59 C O N T E S 3 AIRPORT MASTER PLAN 64 AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE New Zealand Airports Association | February 2017 ABOUT THE NZ AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION The New Zealand Airports Association (NZ Airports) is the national industry voice for airports in New Zealand. It is a not-for-profit organisation whose members operate 37 airports that span the country and enable the essential air transport links between each region of New Zealand and between New Zealand and the world. NZ Airports purpose is to: Facilitate co-operation, mutual assistance, information exchange and educational opportunities for Members Promote and advise Members on legislation, regulation and associated matters Provide timely information and analysis of all New Zealand and relevant international aviation developments and issues Provide a forum for discussion and decision on matters affecting the ownership and operation of airports and the aviation industry Disseminate advice in relation to the operation and maintenance of airport facilities Act as an advocate for airports and safe efficient aviation. Airport members1 range in size from a few thousand to 17 million passengers per year. -

Short Walks in the Invercargill Area Invercargill the in Walks Short Conditions of Use of Conditions

W: E: www.icc.govt.nz [email protected] F: P: +64 3 217 5358 217 3 +64 9070 219 3 +64 Queens Park, Invercargill, New Zealand New Invercargill, Park, Queens Makarewa Office Parks Council City Invercargill For further information contact: information further For Lorneville Lorneville - Dacre Rd North Rd contents of this brochure. All material is subject to copyright. copyright. to subject is material All brochure. this of contents Web: www.es.govt.nz Web: for loss, cost or damage whatsoever arising out of or connected with the the with connected or of out arising whatsoever damage or cost loss, for 8 Email: [email protected] Email: responsibility for any error or omission and disclaim liability to any entity entity any to liability disclaim and omission or error any for responsibility West Plains Rd 9 McIvor Rd 5115 211 03 Ph: the agencies involved in the management of these walking tracks accept no no accept tracks walking these of management the in involved agencies the Waikiwi 9840 Invercargill While all due care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this publication, publication, this of accuracy the ensure to taken been has care due all While Waihopai Bainfield Rd 90116 Bag Private Disclaimer Grasmere Southland Environment 7 10 Rosedale Waverley www.doc.govt.nz Web: Web: www.southerndhb.govt.nz Web: Bay Rd Herbert St Findlay Rd [email protected] Email: Email: [email protected] Email: Avenal Windsor Ph: 03 211 2400 211 03 Ph: Ph: 03 211 0900 211 03 Ph: Queens Dr Glengarry Tay St Invercargill 9840 Invercargill -

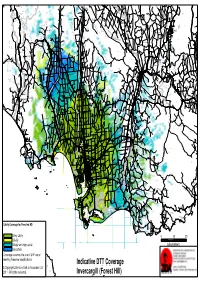

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola. "South - the Endurance of the Old, the Shock of the New." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 60-75. Roger, W. "Six Months in Another Town." Auckland Metro 40 (1984): 155-70. ———. "West - in Struggle Country, Battlers Still Triumph." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 88-99. Young, C. "Newmarket." Auckland Metro 38 (1984): 118-27. 1 General works (21) "Auckland in the 80s." Metro 100 (1989): 106-211. "City of the Commonwealth: Auckland." New Commonwealth 46 (1968): 117-19. "In Suburbia: Objectively Speaking - and Subjectively - the Best Suburbs in Auckland - the Verdict." Metro 81 (1988): 60-75. "Joshua Thorp's Impressions of the Town of Auckland in 1857." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 35 (1979): 1-8. "Photogeography: The Growth of a City: Auckland 1840-1950." New Zealand Geographer 6, no. 2 (1950): 190-97. "What’s Really Going On." Metro 79 (1988): 61-95. Armstrong, Richard Warwick. "Auckland in 1896: An Urban Geography." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1958. Elphick, J. "Culture in a Colonial Setting: Auckland in the Early 1870s." New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1974): 1-14. Elphick, Judith Mary. "Auckland, 1870-74: A Social Portrait." M.A. thesis (History), University of Auckland, 1974. Fowlds, George M. "Historical Oddments." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 4 (1964): 35. Halstead, E.H. "Greater Auckland." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1934. Le Roy, A.E. "A Little Boy's Memory of Auckland, 1895 to Early 1900." Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal 51 (1987): 1-6. Morton, Harry. -

Annual Report 2014-2015

Growing Invercargill 2014-2015 ANNUAL REPORT annual report 2014 / 2015 Table of Contents introduction page 1 introduction 2 Mayor’s Comment 7 Financial Overview 3 Chief Executive’s Comment 9 Financial Prudence Benchmarks 4 Elected Representatives 18 Summary of Service Performance 5 Management Structure 23 Audit Opinion 6 Council Structure 28 Statement of Compliance key projects key key projects page 29 30 Awarua Industrial Development 35 Population Growth 30 Bluff Foreshore Redevelopment 36 Southland Museum and Art Gallery Redevelopment 31 City Centre Revitalisation 37 Urban Rejuvenation 33 Cycling, Walking and Oreti Beach council activities 34 District Plan Review council activities page 39 41 Roading Community Services 59 Sewerage 113 Provision of Specialised Community Services 67 Solid Waste Management 117 Community Development council controlled organisations 121 Housing Care Services 71 Stormwater 125 Libraries and Archives 79 Water Supply 129 Parks and Reserves Development and Regulatory 133 Passenger Transport Services 137 Pools 89 Animal Services 141 Public Toilets 93 Building Control 143 Theatre Services 97 Civil Defence and Emergency Corporate Services Management 145 Democratic Process 101 Compliance management 147 Destinational Marketing 105 Environmental Health financial 149 Enterprise 109 Resource Management 153 Investment Property other information council controlled organisations page 155 156 Invercargill City Holdings Limited 159 Invercargill Venue and Events Management Limited 157 Group Structure 160 Bluff Maritime Museum 158 Southland Museum and Art Gallery Trust financial management page 161 162 Financial Statements 247 Statement of Accounting Policies other information page 267 268 Maori Capacity to Contribute to 269 Working Together - Shared Services Decision-Making 1 annual report 2014 / 2015 introduction Invercargill Introduced In 2013 the Invercargill District had a total population local authorities with 1 being the local authority with of 51,696. -

Whakamana Te Waituna Biodiversity Plan

WHAKAMANA TE WAITUNA BIODIVERSITY PLAN R4701 WHAKAMANA TE WAITUNA BIODIVERSITY PLAN Wire rush rushland amongst mānuka shrubland, near Waituna Lagoon Road. Contract Report No. 4701 February 2019 Project Team: Kelvin Lloyd - Project management Nick Goldwater - Report author Carey Knox - Report author Helen McCaughan - Report author Steve Rate - Report author Fiona Wilcox - Report author Prepared for: Whakamana te Waituna Charitable Trust DUNEDIN OFFICE: 764 CUMBERLAND STREET, DUNEDIN 9016 Ph 03-477-2096, 03-477-2095 HEAD OFFICE: 99 SALA STREET, P.O. BOX 7137, TE NGAE, ROTORUA Ph 07-343-9017; Fax 07-343-9018, email [email protected], www.wildlands.co.nz CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. PROJECT OBJECTIVE 3 3. PROJECT SCOPE 3 4. METHODS 3 5. CULTURAL CONTEXT 4 6. ECOLOGICAL CONTEXT 5 6.1 Waituna Ecological District 5 6.2 Waterways 5 6.3 Protected Natural Areas 7 6.4 Unprotected natural areas 8 6.5 Threatened land environments 8 6.6 Vegetation and habitats 10 6.7 Overview 10 6.8 Wetland vegetation 10 6.9 Terrestrial vegetation 12 6.10 Other vegetation/habitat types 12 6.11 Naturally uncommon ecosystem types 15 7. FLORA 16 7.1 Indigenous species 16 8. FAUNA 18 8.1 Overview 18 8.2 Birds 18 8.3 Lizards 20 8.4 Aquatic fauna 23 8.5 Terrestrial invertebrates 26 9. THREATS TO ECOLOGICAL VALUES 27 9.1 Overview 27 9.2 Land-based activities 27 9.2.1 Excessive catchment inputs of sediment, nutrients, and pathogens 27 9.2.2 Indigenous vegetation clearance 27 9.2.3 Hydrological modification 27 9.2.4 Stock 28 9.2.5 Other adverse activities 28 9.3 Natural phenomena 28 9.3.1 Fire 28 9.3.2 Sea level rise 29 9.4 Effects at landscape scale 29 9.5 Pest animals and plants 29 9.5.1 Pest animals 29 9.5.2 Pest plants 30 © 2019 Contract Report No. -

Public Toilet Facilities

PUBLIC TOILET FACILITIES INVERCARGILL Dee Street Open: 24 hours 62 Dee Street, Invercargill - Exeloo Glengarry Open: 24 hours 87 Glengarry Crescent, Invercargill – Exeloo Invercargill Library 50 Dee Street, Invercargill Open: Library hours 1. Children’s toilet – Ground floor, Children’s Library 2. Public toilet – 2nd floor, Reference Library Wachner Place Restroom Wachner Place Open: Daily 8.00 am – 8.00 pm 20 Dee Street, Invercargill Closed Christmas Day Windsor Shopping Centre Open: 24 hours Cnr Windsor and George Streets, Invercargill – Exeloo BLUFF Stirling Point Public Toilet Open: 24 hours Ward Parade, Bluff – Exeloo Bluff Public Toilet Open: 24 hours 94 Gore Street, Bluff – Exeloo CEMETERIES Eastern Cemetery At Office Open: Office hours East Road, State Highway 1, Invercargill Southland Crematorium At Chapel Open: Office hours Rockdale Road, Invercargill PARKS AND RESERVES Anderson Park Open: Dawn to dusk At Pavilion McIvor Road, Invercargill A228714 Donovan Park Open: Dawn to dusk Bainfield Road, Invercargill Estuary Walkway Open: 24 hours (near the Bond Street carpark) Elizabeth Park Open: By request John Street, Invercargill Makarewa Domain Open: By request Flora Road East, Makarewa Myross Bush Domain Open: By request Mill Road North, Myross Bush Ocean Beach Reserve Open: By request Kirk Crescent, Bluff Omaui Reserve Open: 24 hours Mokomoko Road, Omaui Otatara Scenic Reserve Open: 24 hours Dunns Road, Otatara Queens Park Exeloo near Feldwick Gates Open: Dawn to dusk Exeloo near Winter Gardens Open: Dawn to dusk Children’s playground -

CRT Conference 2020 – Bus Trips

CRT Conference 2020 – Bus Trips South-eastern Southland fieldtrip 19th March 2020 Welcome and overview of the day. Invercargill to Gorge Road We are travelling on the Southern Scenic Route from Invercargill to the Catlins. Tisbury Old Dairy Factory – up to 88 around Southland We will be driving roughly along the boundary between the Southland Plains and Waituna Ecological Districts. The Southland Plains ED is characterized by a variety of forest on loam soils, while the Waituna District is characterized by extensive blanket bog with swamps and forest. Seaward Forest is located near the eastern edge of Invercargill to the north of our route today. It is the largest remnant of a large forest stand that extended from current day Invercargill to Gorge Road before European settlement and forest clearance. Long our route to Gorge Road we will see several other smaller forest remnants. The extent of Seaward forest is shown in compiled survey plans of Theophilus Heale from 1868. However even the 1865 extent of the forest is much reduced from the original pre-Maori forest extent. Almost all of Southland was originally forest covered with the exception of peat bogs, other valley floor wetlands, braided river beds and the occasional frost hollows. The land use has changed in this area over the previous 20 years with greater intensification and also with an increase in dairy farming. Surrounding features Takitimus Mtns – Inland (to the left) in the distance (slightly behind us) – This mountain range is one of the most iconic mountains in Southland – they are visible from much of Southland. -

Dan Davin Re-Visited

40 Roads Around Home: Dan Davin Re-visited Denis Lenihan ‘And isn’t history art?’ ‘An inferior form of fiction.’ Dan Davin: The Sullen Bell, p 112 In 1996, Oxford University Press published Keith Ovenden’s A Fighting Withdrawal: The Life of Dan Davin, Writer, Soldier, Publisher. It is a substantial work of nearly 500 pages, including five pages of acknowledgements and 52 pages of notes, and was nearly four years in the making. In the preface, Ovenden makes the somewhat startling admission that ‘I believed I knew [Davin] well’ but after completing the research for the book ‘I discovered that I had not really known him at all, and that the figure whose life I can now document and describe in great detail remains baffingly remote’. In a separate piece, I hope to try and show why Ovenden found Davin retreating into the distance. Here I am more concerned with the bricks and mortar rather than the finished structure. Despite the considerable numbers of people to whom Ovenden spoke about Davin, and the wealth of written material from which he quotes, there is a good deal of evidence in the book that Ovenden has an imperfect grasp of many matters of fact, particularly about Davin’s early years until he left New Zealand for Oxford in 1936. The earliest of these is the detail of Davin’s birth. According to Ovenden, Davin ‘was born in his parents’ bed at Makarewa on Monday 1 September 1913’. Davin’s own entry in the 1956 New Zealand Who’s Who records that he was born in Invercargill. -

Submission to the Productivity Commission on the Draft Report on Better Urban Planning

SUBMISSION TO THE PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION ON THE DRAFT REPORT ON BETTER URBAN PLANNING 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 The New Zealand Airports Association ("NZ Airports") welcomes the opportunity to comment on the Productivity Commission's Draft Report on Better Urban Planning ("Draft Report"). 1.2 NZ Airports has submitted on the Resource Legislation Amendment Bill ("RLAB") and presented to the Select Committee on the RLAB, and has also submitted on the Proposed National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity ("NPS-UDC"). Our members have also been closely involved in extensive plan review processes in Auckland and Christchurch. Such participation is costly and time consuming - but necessary, given the important role the planning framework plays in our operations. 1.3 As discussed in our previous submissions, it is fundamental to the development of productive urban centres that residential and business growth does not hinder the effective current or future operation of New Zealand's airports. 1.4 In our view, the Draft Report does not adequately acknowledge the importance of significant infrastructure like airports in the context of urban planning and the need to effectively manage reverse sensitivity effects on such infrastructure. This is reflected in some of the Commission's recommendations which seek to limit notification and appeal rights and introduce the ability to amend zoning without using the Schedule 1 process in the Resource Management Act 1991 ("RMA"). NZ Airports has major concerns with such recommendations as they stand to significantly curtail the ability of infrastructure providers to be involved in planning processes and have their key concerns, such as reverse sensitivity effects, taken into account. -

Regional Brand Toolkit

New Zealand New / 2019 The stories of VERSION 3.0 VERSION Regional Brand Toolkit VERSION 3.0 / 2019 Regional Brand Toolkit The stories of New Zealand Welcome to the third edition of the Regional Brand Toolkit At Air New Zealand I’m pleased to share with you the revised version our core purpose of the Regional Brand Toolkit featuring a number of updates to regions which have undergone a is to supercharge brand refresh, or which have made substantial New Zealand’s success changes to their brand proposition, positioning or right across our great direction over the last year. country – socially, environmentally and We play a key role in stimulating visitor demand, growing visitation to New Zealand year-round economically. This is and encouraging visitors to travel throughout the about making a positive country. It’s therefore important we communicate AIR NEW ZEALAND impact, creating each region’s brand consistently across all our sustainable growth communications channels. and contributing This toolkit has proven to be a valuable tool for to the success of – Air New Zealand’s marketing teams, providing TOOLKIT BRAND REGIONAL New Zealand’s goals. inspiring content and imagery which we use to highlight all the regions which make our beautiful country exceptional. We’re committed to showcasing the diversity of our regions and helping to share each region’s unique story. And we believe we’re well placed to do this through our international schedule timed to connect visitors onto our network of 20 domestic destinations. Thank you to the Regional Tourism Organisations for the content you have provided and for the ongoing work you’re doing to develop strong and distinctive brands for your regions. -

NZ Gazette 1876

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently This sampler file includes the title page and various sample pages from this volume. This file is fully searchable (read search tips page) but is not FASTFIND enabled New Zealand Gazette 1876 Ref. NZ0110-1876 ISBN: 978 1 921315 21 3 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by the University of Queensland Library http://www.library.uq.edu.au Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages.