History of India-I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits of Empire in Ancient Afghanistan Rule and Resistance in the Hindu Kush, Circa 600 BCE–650 CE

THE LIMITS OF EMPIRE IN ANCIENT AFGHANIStaN RULE AND RESISTANCE IN THE HINDU KUSH, CIRCA 600 BCE–650 CE PROGRAM & ABSTRACTS The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago The Franke Institute for the Humanities October 5–7, 2016 Wednesday, October 5 — Franke Institute Thursday, October 6 — Franke Institute Friday, October 7 — Classics 110 THE LIMITS OF EMPIRE IN ANCIENT AFGHANIStaN RULE AND RESISTANCE IN THE HINDU KUSH, CIRCA 600 BCE–650 CE Organized by Gil J. Stein and Richard Payne The Oriental Institute — The University of Chicago Co-sponsored by the Oriental Institute and the Franke Institute for the Humanities — The University of Chicago PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 5, 2016 — Franke InsTITUTE KEYNOTE LECTURE 5:00 Thomas Barfield “Afghan Political Ecologies: Past and Present” THURSDAY, OCTOBER 6, 2016 — Franke InsTITUTE 8:00–8:30 Coffee 8:30–9:00 Introductory Comments by Gil Stein and Richard Payne SESSION 1: aCHAEMENIDS AND AFTER 9:00–9:45 Matthew W. Stolper “Achaemenid Documents from Arachosia and Bactria: Administration in the East, Seen from Persepolis” 9:45–10:30 Matthew Canepa “Reshaping Eastern Iran’s Topography of Power after the Achaemenids” 10:30–11:00 Coffee Break Cover image. Headless Kushan statue (possibly Kanishka). Uttar Pradesh, India. 2nd–3rd century CE Sandstone 5’3” Government Museum, Mathura. Courtesy Google LIMITS OF EMPIRE 3 SESSION 2: HELLENISTIC AND GRECO-BACTRIAN REGIMES 11:00–11:45 Laurianne Martinez-Sève “Greek Power in Hellenistic Bactria: Control and Resistance” 11:45–12:30 Osmund Bopearachchi “From Royal Greco-Bactrians to Imperial Kushans: The Iconography and Language of Coinage in Relation to Diverse Ethnic and Religious Populations in Central Asia and India” 12:30–2:00 Break SESSIOn 3: KUSHAN IMPERIALISM: HISTORY AND PHILOLOGY 2:00–2:45 Christopher I. -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage New Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISBN 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San irst Printing, 2002 " 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 " 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety, for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma, is allowed after prior notification to the author. New Cover Design ,nset photo shows the famous Reclining .uddha image at Kusinara. ,ts uni/ue facial e0pression evokes the bliss of peace 1santisukha2 of the final liberation as the .uddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the 3reat Stupa of Sanchi located near .hopal, an important .uddhist shrine where relics of the Chief 4isciples and the Arahants of the Third .uddhist Council were discovered. Printed in ,uala -um.ur, 0alaysia 1y 5a6u6aya ,ndah Sdn. .hd., 78, 9alan 14E, Ampang New Village, 78000 Selangor 4arul Ehsan, 5alaysia. Tel: 03-42917001, 42917002, a0: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATI2N This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to ,ndia from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in .uddhism, have made those 6ourneys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

The Characteristic of Mudrarakhasa and Analysis on Present Politics

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2017; 3(1): 14-15 International Journal of Sanskrit Research2015; 1(3):07-12 ISSN: 2394-7519 IJSR 2017; 3(1): 14-15 The characteristic of mudrarakhasa and analysis on © 2017 IJSR present politics www.anantaajournal.com Received: 05-11-2016 Accepted: 06-12-2016 Ratan Chandra Sarkar Ratan Chandra Sarkar Chakchaka High School (Hs), Introduction Chakchaka, Dist- Cooch Behar, The plays of Sanskrit literature is totally different in its form, specially of thoughts and action. West Bengal India Here we find a collaboration of history as well as politics which is not rather suitable to the modern context. In Sanskrit dramas we find ‘Rasha’ is the more dominant while in Mudrarakhasa is a heroic play. A play deals with various actions but here we find from one act th to 7 act ‘Bir Rasha’ only is the main flow. The great diplomat Chanakya never participated in any battle or did any blood sheed to intensity ‘Bir Rash’ in this play – Here we find there is no hero or heroine and there is no action of love. Only the wife of Chandan Das appeared for a movement in 7th act and though the wife of Amartya rakhas was abducted and sheltered at the house of Chandan Das, they did not directly utter anything. No Vidushak was there to create any fun like other plays. The presence of Vidushak is not necessary during dramatic excitement. Here one character is interingled with another, like Amartyarakhas is the rival of chanakya. Both of them are great diplomat. Both wants their rival to be perished. -

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage ew Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISB: 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San First Printing, 2002 – 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 – 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety , for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma , is allowed after prior notification to the author. ew Cover Design Inset photo shows the famous Reclining Buddha image at Kusinara. Its unique facial expression evokes the bliss of peace ( santisukha ) of the final liberation as the Buddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the Great Stupa of Sanchi located near Bhopal, an important Buddhist shrine where relics of the Chief Disciples and the Arahants of the Third Buddhist Council were discovered. Printed in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia by: Majujaya Indah Sdn. Bhd., 68, Jalan 14E, Ampang New Village, 68000 Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Tel: 03-42916001, 42916002, Fax: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATIO This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to India from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in Buddhism, have made those journeys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

The Mauryan Empire Opens a New Era in the History Of

Winmeen Tnpsc Group 1 & 2 Self Preparation Course 2018 History Part - 7 7] Maurya Empire MAURYAN EMPIRE NOTES Mauryan Empire (321 – 184 BC) The foundation of the Mauryan Empire opens a new era in the history of India and for the first time, the political unity was achieved in India. The history writing has also become clear from this period due to accuracy in chronology and sources. Besides plenty of indigenous and foreign literary sources, a number of epigraphical records are also available to write the history of this period. RISE OF MAURYAS The last of the Nanda rulers, Dhana Nanda was highly unpopular due to his oppressive tax regime. Also, post Alexander’s invasion of North-Western India, that region faced a lot of unrest from foreign powers. They were ruled by Indo-Greek rulers. Chandragupta, with the help of an intelligent and politically astute Brahmin, Kautilya usurped the throne by defeating Dhana Nanda in 321 BC. 1 www.winmeen.com | Learning Leads to Ruling Winmeen Tnpsc Group 1 & 2 Self Preparation Course 2018 Chandragupta Maurya (322 – 298 B.C.) Chandragupta Maurya was the first ruler who unified entire country into one political unit, called the Mauryan Empire. He had captured Pataliputra from Dhanananda, who was the last ruler of the Nanda dynasty. He didn’t do achieve this feat alone, he was assisted by Kautilya, who was also known as Vishnugupta or Chanakya. Some scholars think that Chanakya was the real architect of this empire. After establishing his reign in the Gangetic valley, Chandragupta Maurya marched to the northwest and conquered territories upto the Indus. -

VIOLENCE and DISRUPTION in SOCIETY a Study of the Early

VIOLENCE AND DISRUPTION IN SOCIETY A Study of the Early Buddhist Texts by Elizabeth J. Harris The Wheel Publication No. 392/393 ISBN 955-24-0119-4 Published in 1994 Copyright 1990 by Elizabeth J. Harris Originally published in //Dialogue//, New Series Vo. XVII (1990) by The Ecumenical Institute for Study & Dialogue, 490/5 Havelock Road, Colombo 6, Sri Lanka. Reprinted in the Wheel Series with the consent of the author and the original publisher. BUDDHIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY KANDY SRI LANKA * * * DharmaNet Edition 1994 Formatted for DharmaNet by John Bullitt via DharmaNet by arrangement with the publisher. DharmaNet International P.O. Box 4951, Berkeley CA 94704-4951 * * * * * * * * CONTENTS Introduction Part 1. The Forms of Violence Part 2. Reasons for Buddhism's Attitude to Violence Part 3. The Roots of Violence Part 4. Can Violent Tendencies Be Eradicated? Conclusion Notes * * * * * * * * INTRODUCTION At 8.15 a.m. Japanese time, on August 6th 1945, a U.S. plane dropped a 1 bomb named "Little Boy" over the center of the city of Hiroshima. The total number of people who were killed immediately and in the following months was probably close to 200,000. Some claim that this bomb and the one which fell on Nagasaki ended the war quickly and saved American and Japanese lives -- a consequentialist theory to justify horrific violence against innocent civilians. Others say the newly developed weapons had to be tested as a matter of necessity. Hiroshima and Nagasaki ushered in a new age. Humankind's tendency towards conflict and violence can now wipe out the entire human habitat. -

Magadha-Empire

Rise & Growth of Magadha Empire [Ancient Indian History Notes for UPSC] The Magadha Empire encompasses the rule of three dynasties over time - Haryanka Dynasty, Shishunaga Dynasty, and Nanda Dynasty. The timeline of the Magadha Empire is estimated to be from 684 BCE to 320 BCE. Read about the topic, 'Rise and Growth of the Magadha Empire,' in this article; which is important for the IAS Exam (Prelims - Ancient History and Mains - GS I & Optional). Rise of Magadha Notes for UPSC Exam The four Mahajanapadas - Magadha, Kosala, Avanti and Vatsa were vying for supremacy from the 6th century BCE to the 4th century BCE. Finally, Magadha emerged victorious and was able to gain sovereignty. It became the most powerful state in ancient India. Magadha is situated in modern Bihar. Jarasandha, who was a descendant of Brihadratha, founded the empire in Magadha. Both are talked about in the Mahabharata. Read about the 16 Mahajanapadas in the linked article. Magadha Empire - Haryanka Dynasty The first important and powerful dynasty in Magadha was the Haryanka dynasty. Bimbisara (558 BC – 491 BC) • Son of Bhattiya. • According to Buddhist chronicles, Bimbisara ruled for 52 years (544 BCE - 492 BCE). • Contemporary and follower of the Buddha. Was also said to be an admirer of Mahavira, who was also his contemporary. • Had his capital at Girivraja/Rajagriha (Rajgir). o It was surrounded by 5 hills, the openings of which were closed by stone walls on all sides. This made Rajagriha impregnable. • Also known as Sreniya. • Was the first king to have a standing army. Magadha came into prominence under his leadership. -

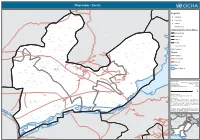

Overview - Swabi

Overview - Swabi Tor Ghar Legend Takhto Sar ! Shamma Khui ! Shama Shapla !^! ! National ! Khanpur ! ! Shahole !! Natian ! Khanpur Ajarh Province Post Gadai ! Natian ! Rizzar !!! District ! Mir Dandikot Sherdarra ! Shahe ! Sherdarah ! Settlements Mir Shahai Dandai ! Tor Gat ! Naranji Administartive Boundaries Mardan ! Badrai Chatara ! Buner ! Kund International Miralai ! Mehr Kamar Burai ! ! Bako ! Ali Dhand Bural ! Birgalai Mir Dai ! ! Pirgalai Khisha Khesha ! Naogram ! Provincial Kaniza Dheri ! ! Lakha Tibba Dheri Lakha Madda Khel Jabba ! Tiga Dheri Ghulama ! Mazghund ! Sikandarabad ! Muz Ghunar ! Jabba District Parmulai Bagga ! Jabba Purmali ! Ganikot ! ! Ganrikot Kodi Dherai Kodi Dheri ! Utla Bahai Baho Leran ! ! Satketar ! Palosai ! Gabai Amankot ! Salketai Ghabasanai ! Tehsil Bar Amrai Gabasanrai ! ! ! Gumbati Dheri Gumbat Dherai Amral Bala Bar Amral Bala ! Gunj Gago ! Dheri ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sangbalai ! Dherai ! Gani Chhatra Bar Dewalgari ! ! Line of control ! Punrawal Shewa ! Gangodher ! Aziz Dheri Banda ! Shingrai ! ! ! Katar Dheri ! Seri ! Kuz Amrai ! Achelai Rasoli Dheri Inian Dheri ! Gangu Dheri Shingrai Kuz Dewalgari ! ! Khalil ! ! ! Gangudhei Seri Injan Asota Sharif Asota Gangudher Makia ! ! Coastline Dheri Nuro Banda Chini Rafiqueabad ! Dheri ! Nakla Jogia ! Takhtaband Dheri Dagi ! Banda ! ! Spin ! Girro Sherghund Kani Aro Bore Badga ! Banda ! Katgram ! ! Sheikhjana ! Shaikh Jana Dakara Banda Roads ! Sukaili ! ! Ismaila Tali ! Adina ! ! ! Nawe Kili Pal Qadra ! Mangal Dheri Sandwa ! Chai ! Kalu Khan ! Shewa Chowk Aio Kolagar -

Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Mindfulness Studies Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-6-2020 Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Meill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Meill, Kyung Peggy, "Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā" (2020). Mindfulness Studies Theses. 29. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/mindfulness_theses/29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mindfulness Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ i Diversity in the Women of the Therīgāthā Kyung Peggy Kim Meill Lesley University May 2020 Dr. Melissa Jean and Dr. Andrew Olendzki DIVERSITY IN THE WOMEN OF THE THERĪGĀTHĀ ii Abstract A literary work provides a window into the world of a writer, revealing her most intimate and forthright perspectives, beliefs, and emotions – this within a scope of a certain time and place that shapes the milieu of her life. The Therīgāthā, an anthology of 73 poems found in the Pali canon, is an example of such an asseveration, composed by theris (women elders of wisdom or senior disciples), some of the first Buddhist nuns who lived in the time of the Buddha 2500 years ago. The gathas (songs or poems) impart significant details concerning early Buddhism and some of its integral elements of mental and spiritual development.