The Nation Behaves Well If It Treats the Natural Resources As Assets Which It Must Turn Over to the Next Generation Increased, and Not Impaired in Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F-7-141 Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area

F-7-141 Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 10-11-2011 CAPSULE SUMMARY Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area MIHJP# F-7-141 Dickerson vicinity Frederick and Montgomery counties, Maryland NRMA=1974 Public The Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area (NRMA) occupies 2,011 acres that includes property along both banks of the lower Monocacy River and most of the Furnace Branch watershed in southeastern Frederick and western Montgomery counties. The area is predominantly rural, comprising farmland and rolling and rocky wooded hills. Monocacy NRMA's main attraction is the Monocacy River, which was designated a Maryland Scenic River in 1974. The NRMA began in 1974 with the acquisition of the 729-acre Rock Hall estate. -

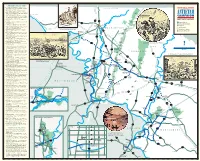

Antietam Map Side

★ ANTIETAM CAMPAIGN SITES★ ★ Leesburg (Loudoun Museum) – Antietam Campaign To ur begins here, where Lee rested the Army of Northern MASON/DIXON LINE Virginia before invading Maryland. ★ Mile Hill – A surprise attack led by Confederate Col. Thomas Munford on Sept. 2, 1862, routed Federal forces. ★ White’s Ferry (C&O Canal NHP) – A major part of Lee’s army forded the Potomac River two miles north of this mod- ern ferry crossing, at White’s Ford. To Cumberland, Md. ★ White’s Ford (C&O Canal NHP) – Here the major part of the Army of Northern Virginia forded the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5-6, 1862, while a Confederate band played “Maryland! My Maryland!” ★ Poolesville – Site of cavalry skirmishes on September 5 & 8, 1862. 81 11 ★ Beallsville – A running cavalry fight passed through town Campaign Driving Route on September 9, 1862. 40 ★ Barnesville – On September 9, 1862, opposing cavalry Alternate Campaign Driving Route units chased each other through town several times. Rose Hill HAGERSTOWN Campaign Site ★ Comus (Mt. Ephraim Crossroads) – Confederate cavalry Cemetery fought a successful rearguard action here, September 9-11, Other Civil War Site 1862, to protect the infantry at Frederick. The German Reformed Church in Keedysville W ASHINGTON ★ Sugarloaf Mountain – At different times, Union and was used as a hospital after the battle. National, State or County Park Confederate signalmen atop the mountain watched the 40 I L InformationInformation or Welcome Center opposing army. Williamsport R A T ★ Monocacy Aqueduct (C&O Canal NHP) – Confederate (C&O Canal NHP) troops tried and failed to destroy or damage the aqueduct South Mountain N on September 4 & 9, 1862. -

ALONG the TOWPATH a Quarterly Publication of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Association

ALONG THE TOWPATH A quarterly publication of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Association Concerned with the conservation of the natural and historical environment of the C&O Canal and the Potomac River Basin. VOLUME XLIII June 2011 Number 2 The C&O Canal in the Civil War The Sesquicentennial Year 1861 - 2011 With our nation commemorating the Sesquicentennial of the Civil Ferry. The owner of the boats, Charles Wenner, appealed War, it is appropriate that we look back at some of the varying ways to the sheriff of Frederick County, Maryland, for help. The in which the C&O Canal was impacted by the conflict. Because of its sheriff was powerless to intervene, however, and referred location along a portion of Maryland‟s southern border with Vir- the matter to Governor Thomas Holliday Hicks. In another ginia—the boundary between the North and South—the canal would instance, the Confederates seized a boatload of salt. Hicks soon be an object of contention between the opposing sides. This issue would soon receive a petition from a group of citizens from will present three different aspects of the conflict. Montgomery County, Maryland, asking for protection of their grain on the canal.1 Leading off is a contribution from Tim Snyder, author of the forth- coming book, "Trembling in The Balance: The Chesapeake and Ohio Since interference with canal navigation was only one Canal during the Civil War," soon to be published by Blue Mustang of a number of border violations committed by the Virginia Press. Grant Reynolds presents a more human side of the war, and troops from Harpers Ferry, Governor Hicks referred the Mike Dwyer, our "man in Montgomery," relates a tale of behind-the- matters to the Maryland General Assembly. -

C&O Canal Trail to History

C &O Canal {TRAIL to HISTORY} POINT OF ROCKS BRUNSWICK HARPERS FERRY www.canaltrust.org C &O Canal {TRAIL to HISTORY} Take a journey into the rich history of our Canal Towns along the C&O Canal towpath. Explore our region in your car, ride a bike, raft the river or take a leisurely stroll in our Pivotally located along the West Virginia- historic towns. Visit our historical parks and learn about our region’s rich history. Pioneer settlement, transportation Maryland border, Harpers Ferry, Brunswick, innovations, struggles for freedom—it all happened here. and Point of Rocks are steeped in Civil Visit, explore and enjoy! War history, C&O Canal and B&O Railroad heritage, and local lore. This charming area encompasses approximately 12 miles on the C&O towpath between Harpers Ferry and Point of Rocks, with Brunswick located about halfway. In addition to the area’s memorable historical sites, several outstanding hiking trails and scenic vistas are located in or nearby the towns, and the area is home to three national parks. 2 3 POINT OF ROCKS } POINT OF ROCKS As its name indicates, Point of Rocks stands out as a natural landmark along the Potomac River and the C&O Canal. Towering above the present railroad tunnel that was constructed after the Civil War, the “Point” featured Union Army artillery and a wartime signal tower that relayed messages between Sugarloaf Mountain and Leesburg, Virginia. While the town Point of Rocks train station Point of Rocks saw Today’s Point of Rocks is a great place to detour off the no major Civil War towpath to find refreshment or to see the distinguished Point battles, it was the site of Rocks train station. -

LIFE in a WAR ZONE a Guide to the Civil War in Montgomery County, Maryland

LIFE IN A WAR ZONE A Guide to the Civil War in Montgomery County, Maryland Civil War Sesquicentennial Commemoration 1861–1865 www.HeritageMontgomery.org Among the organizations pleased to support this Heritage Montgomery publication is the C&O Canal Association Post Office Box 366 Glen Echo, MD 20812-0366 301-983-0825 INTRODUCTION ovember 2010 marks the 150th anniversary N of the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States and the beginning of Montgomery County’s commemoration of the Civil War Sesquicentennial. Heritage Montgomery has produced a documentary video, Life in a War Our activities include hikes, bike and Zone: Montgomery County during the Civil War, bringing canoe trips, volunteer programs, and to life some of the stories of the Civil War years in Montgomery County. Please visit the Heritage special projects to support the C&O Montgomery website, www.HeritageMontgomery.org Canal National Historical Park. Please to view this film. Heritage Montgomery wants to join us! Information about membership inspire the curiosity of county residents and visitors is available at our web site: alike, encouraging them to travel around the county to experience our area’s fascinating history first-hand. Use this brochure as a guide when you visit the www.candocanal.org towns mentioned and learn about the events that took place here 150 years ago. See how some places have changed dramatically, while others have hardly changed at all … and imagine the events that › Please be respectful when touring areas with private happened right here in Montgomery County. homes of historic interest as well as places of worship The Heritage Tourism Alliance of Montgomery County and cemeteries. -

The Monocacy Aqueduct

HISTORIC STRUCTURE REPORT THE MONOCACY AQUEDUCT HISTORICAL DATA CHESAPEAKE AND OHIO CANAL NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK MD. – D.C.- W.VA. by Harlan D. Unrau DENVER SERVICE CENTER HISTORIC PRESERVATION TEAM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DENVER, COLORADO January 1976 i CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iii ADMINISTRATIVE DATA and RECOMMENDATIONS iv PREFACE and NOTE FOR THIS EDITION vi I. HOVEY AND LEGG BEGIN CONSTRUCTION 1 II. A. P. OSBORN CONTINUES CONSTRUCTION 12 III. BYRNE AND LEBARON COMPLETE THE AQUEDUCT 20 IV THE MONOCACY AQUEDUCT FROM 1834 TO 1950 33 AFTERWORD: THE STABILIZATION OF THE MONOCACY AQUEDUCT 38 APPENDIXES 40 A: Estimates of Work Done on Aqueduct No. 2 41 B: Payments Made for the Construction of Aqueduct No. 2 62 C: T. H. S. Boyd’s Description of the Temporary Railroad 68 From Sugarloaf Mountain to Aqueduct No. 2 D: Excerpt from “Report on Survey of Aqueduct and Miscellaneous Drainage 69 And Overpass Structures on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal” By C. D. Geisler, 1950 ILLUSTRATIONS 71 BIBLIOGRAPHY 82 ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Photograph made in 1936 of the berm side of the Monocacy Aqueduct. 72 2. Photograph made in 1936 of the berm side of the Monocacy Aqueduct, 72 looking west. 3. Photograph made in 1936 of the canal bed and towpath and berm parapets 73 of the Monocacy Aqueduct, looking east. 4. Photograph made in 1936 of the southeast abutment wall of Monocacy Aqueduct. 73 5. Photograph made in 1936 of the towpath parapet, coping and iron railing 74 of the Monocacy Aqueduct, looking south. -

EXPLORE the OUTDOORS Frederick County, Maryland Take a Break from Your Daily Grind and Become One with the Great Outdoors in Frederick County

EXPLORE THE OUTDOORS Frederick County, Maryland Take a break from your daily grind and become one with the great outdoors in Frederick County. Explore more than 40,000 acres of public parklands, a 78-foot cascading waterfall, and picturesque mountain trails just waiting to be conquered. With four distinct seasons and adventures to match, even the most experienced outdoor enthusiast can engage in something new each time they visit and everywhere they look. Whether you are here to camp, hike, raft, birdwatch, fish or swim, Frederick County has something for you. SO, LOG OFF, SHUT DOWN, AND GET OUTSIDE! HOG ROCK An abundance of VISTA hiking trails weave MILEAGE 1.0 mile their way through HIKE TIME the county, offering 45 minutes endless opportunities DIFFICULTY for hikers to discover Easy Frederick on foot. The whole family will enjoy CUNNINGHAM the short hike to Maryland’s FALLS highest cascading waterfall at MILEAGE Cunningham Falls State Park, 2.8 miles or the breathtaking natural HIKE TIME 90 minutes landforms like Chimney Rock and Hog Rock at Catoctin Mountain DIFFICULTY Moderate Park. For the history buff looking for an outdoor adventure, check out the trails at South Mountain WOLF ROCK & State Battlefield or Monocacy CHIMNEY ROCK National Battlefield and hike MILEAGE where soldiers once marched. 3.9 mile Along each trail, breathe in the HIKE TIME fresh air, take in the scenic views 2 hours and wildlife, and see Frederick in DIFFICULTY a whole new light. Semi-Strenuous Whether you just lost your training wheels, or you’ve been counting your pedal revolutions for years, Frederick offers routes and trails for riders of all skill levels. -

History and Cultural Resources

HISTORY AND CULTURAL RESOURCES Photo by Dial Keju Archaeological and historic resources are irreplaceable components of local heritage, and once destroyed, cannot be replaced. Over three decades ago, in 1981, a nationwide river study conducted by the National Park Service identified the Monocacy River as an outstanding archaeological resource of national significance. The Maryland Scenic and Wild Rivers Act’s “Declaration of Policy” makes specific reference to the importance of recognizing the outstanding “historic values” of a designated scenic river and its adjacent lands. Why is this important to the residents of Frederick and Carroll Counties? The preservation of historic and archaeological resources contributes to the quality of people’s lives by increasing the community’s knowledge of its heritage, providing residents and visitors with a rich sense of place, and conserving natural and cultural resources. Acknowledgment and care of historic and cultural resources promotes community pride and can vastly improve the visual quality of the landscape. Preservation also serves as an important driver of regional tourism and related economic development activities. The Monocacy River Valley is an area rich in cultural history. Native Americans caught fish in the Potomac and Monocacy Rivers and hunted for an abundance of wild game. European settlers were also attracted to the Monocacy region for the same reasons. By the time Frederick and Carroll Counties were chartered, farming had become the local economic mainstay. Early historical uses of the area’s land and water resources have shaped land use and development patterns that are still prevalent today. As the region grows and changes around us, the historical and cultural resources along the Monocacy River continue to offer a fascinating glimpse into the recent and distant past. -

"A Savage Continual Thunder" the 1862 Maryland Campaign: Confederate Invasion of the North

"A Savage Continual Thunder" The 1862 Maryland Campaign: Confederate invasion of the North "If we should be defeated, the consequences to the country would be disastrous in the extreme." ~ Union General George B. McClellan 1 2 Southern Success Taking the War North On August 30th, 1862, Confederate Gen. James Longstreet, in command of Until the launch of the Maryland Campaign, every major battle of the war the Army of Northern Virginia's right wing, pushed his massive columns had been fought on southern soil. The citizens of Virginia had seen their forward, smashing into the Union left. The Union Army of Virginia faced homes occupied and their farms stripped again and again. Defending that annihilation. Only a heroic stand by northern troops, first on Chinn Ridge land and those people had been the stated mission of Confederate officers and then once again on Henry Hill, bought time for the army to make and soldiers. Now, they would be the invaders. Some of the men expressed a hasty retreat. Finally, under cover of darkness the defeated Federals opposition to this, but many realized that if the Confederacy was going withdrew across Bull Run towards the defenses of Washington. to win the war, a major victory on Union soil was necessary. And most realized that the chances of winning that victory were greatly increased by The next day, Union resistance at the Battle of Chantilly blunted the having Lee leading them. Confederate's advance toward Washington, D.C., but did little to weaken southern confidence. Even though the army under Gen. Robert E. -

The Aqueduct Issue the Monocacy·· Lonc May She Stand?

C & 0 Canal Association concerned with the consetvation of the natural and historical environment of the C & 0 Canal and the Potomac River Basin VOLUME XXVII SEPTEMBER 1995 NUMBER3 THE AQUEDUCT ISSUE THE MONOCACY·· LONC MAY SHE STAND? Monocacy Aqueduct, undated photo from the Tom Hahn collection Completed eight score and three years ago the Monocacy Aqueduct still rises before us, grand and magnificent. All who come upon it on towpath or river marvel at its beauty of line and proportion. Both a monument of early 19th century engineering and an emblem of the Canal itself, it was the crowning achievement of the builders of the waterway's eleven aqueducts. On its sturdy piers it bore aloft the full weight of the Canal's waters and commerce: for more than nine decades flotillas of laden canal boats crossed back and forth over the Monocacy River. Today it does the less arduous duty of conveying hikers, strollers, fisherman, and sightseers across the Monocacy. Last but not least it remains the main link of the chain of aqueducts that makes the canal park a continuous and integrated entity. Our forebears took great pride in the Aqueduct. Marylanders depicted it on fmely wrought silver platters for state banquets and dubbed it one of the state's "seven wonders." The question now before us is: "Do we of the present generation retain enough pride in this superb historic structure not to let it collapse in neglect as its lesser cousin, the Catoctin, did?" The latter's underwater piers were gradually undercut and a flash flood took it down in 1973. -

Fighting on the Border

Fighting on the Border The heated words and actions of early 1861 turned into bullets and cannon balls on April 12 when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter. Mid-Maryland and the Virginia countryside bordering the Potomac River were quickly transformed into a war zone as both sides recognized the strategic military significance of the invisible dividing line. A scene from the Battle of Antietam, painted by James Hope, who had been a participant in the fighting (Antietam National Battlefield) For the next four years, this border region from south-central Pennsylvania through mid- Maryland and into Virginia was the scene of some of the most important military battles in American history. Antietam, Gettysburg, Monocacy, and many smaller engagements helped determine the outcome of the Civil War and the fate of the United States. Opening Salvos Before the war commenced, there had been fiery debate throughout the region on the legality of secession, slavery, the sanctity of the Union versus the rights of states, and last-minute compromises. Once fighting began, however, choices became clearer and sides were chosen. Pennsylvania quickly pledged allegiance to the Union, and Virginia likewise to the Confederacy. There were opposing voices in both states, but they were quickly silenced by the ardent war spirit of the majority. Citizens in Maryland were more conflicted. As a border slave state, Maryland had ties to both the North and the South. Baltimore and southern Maryland were generally more sympathetic with the South, and the mid-Maryland region more with the Union, but loyalties were strained throughout the state. -

WAKE up in HISTORY! a PLANNING GUIDE for STUDENT GROUP TOURS in MID-MARYLAND’S HEART of the CIVIL WAR 2 Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area | Attractions

WAKE UP IN HISTORY! A PLANNING GUIDE FOR STUDENT GROUP TOURS IN MID-MARYLAND’S HEART OF THE CIVIL WAR 2 Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area | Attractions LOCATED BETWEEN THE POTOMAC RIVER AND THE MASON-DIXON LINE, Mid-Maryland’s Heart of the Civil War Heritage Area is ideally situated to serve as a “base camp” for class trips to Washington D.C., Gettysburg, Antietam, Harpers Ferry, Baltimore and other popular destinations. This guide will help tour operators and trip leaders plan a transformative student travel experience that is fun, affordable, and group-friendly. While here, your students may: » Encounter iconic sites in American history » Enjoy lively evening activities » Explore the outdoors with adventures along waterways and trails » Experience arts and entertainment venues with authentic charm » Expand their perspectives on the past and present We look forward to welcoming your student group to the Heart of the Civil War! HEART OF THE CIVIL WAR HERITAGE AREA (301) 600-4031 | 151 S. East Street, Frederick, MD 21701 [email protected] | www.HeartoftheCivilWar.org HeartoftheCivilWar.org 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Map ................................................................................. 4 Immersive Attractions ...................................................... 6 Sample Itineraries ........................................................... 14 Dining in the Heart of the Civil War ..................................16 Evening and Extracurricular Activities ..............................18 Group Overnights in the Heart of the Civil War ................. 20 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE Peruse this guide to learn about some of the most in-demand student attractions, dining, and lodging options in Carroll, Frederick, and Washington Counties in Maryland. This, however, is just a sampler of the array of custom itineraries that can be shaped to fit your group’s needs.