History and Cultural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Water Resources Compared

Water Resources Overview The goals of the Water Resources Chapter are listed below: - Protect the water supply from pollution and encroachment of developments. - Provide an adequate and safe drinking water supply to serve the existing and future residents of the City of Frederick. - Provide an adequate capacity of wastewater treatment with effluent meeting all necessary regulatory requirements for existing and future residents of the City. - Restore and protect water quality and contribute toward meeting the water qualityby striving to meet or exceed regulatory requirements. for water quality. This will require addressinginclude current water quality impacts as well as future impacts from land development and population growth. - Develop adequate stormwater management. - Protect the habitat value of the local and regional rivers and streams. - Efficiently use public dollars for infrastructure that ensures sustainable, safe, and adequate supply of water for all residents. The City is committed to ensuring water and wastewater (sewer) capacity for both existing and new developments andwhile minimizing the negative impacts of stormwater runoff. In 2002, the City established the Water and Sewer Allocation System to make certain that adequate treatment capacity for potable water and wastewater is in place for new growth prior to approval. In 2012, Ordinance G-12-13 was adopted which updated the allocation process and combined it with it the Impact Fees payable for water and sewer service. The City adopted an Adequate Public Facilities Ordinance (APFO) in 2007 that allows development to proceed only after it has been demonstrated that sufficient infrastructure exists or will be created in the water and wastewater systems. -

NCHRP Report 350, Which Specifies Speeds, Angles of Collision, and Vehicle Types, As Well As Defines Success Or Failure in the Testing

93 H. CASE STUDIES The following is a selection of case studies that illustrate application of the principles and thought process A B C D E F G H behind CSD/CSS. The case stud- Effective Reflecting Achieving Ensuring Safe ies were assembled from materials Introduction About this Decision Community Environmental and Feasible Organizational Case Appendices and interviews conducted with pilot to CSD Guide Making Values Sensitivity Solutions Needs Studies state representatives, as well as with Management Structure other agencies contacted during the research project. The case studies Problem Definition are geographically diverse. They Project Development and illustrate a wide range of project Evaluation Framework contexts, from rural roads to urban Alternatives Development streets. They demonstrate that one can be context sensitive when dealing Alternatives Screening with a freeway, an arterial, or a local Evaluation and Selection road. In one case, they show that the Implementation mission of a transportation agency ���������� can and should go beyond providing for safe and efficient transportation. They represent both small projects and substantial efforts. Most of all, the case studies show how project success can be achieved by following the framework discussed here, and applying the right resources to solve a problem. National Cooperative Highway Research Program Report 480 Section H: Case Studies 94 This page intentionally left blank Section H: Case Studies A Guide to Best Practices for Achieving Context Sensitive Solutions 95 CASE STUDY NO. 1 MERRITT PARKWAY GATEWAY PROJECT GREENWICH, CONNECTICUT Both the volume of traffic and its character and operations SETTING have changed over time. The Parkway now carries traffic The Merritt Parkway (The Parkway) was constructed in in excess of 50,000 vehicles per day in some segments. -

MARCH 29 2007 Frederick County Mills ACCOMMODATION FACTORY

MARCH 29 2007 Frederick County Mills ACCOMMODATION FACTORY ( ) David Foute advertised wool carding at Accommodation Factory, Dumb Quarter extended, Frederick-Town Herald, June 23, 1827. ADAMS FULLING MILL (9) Frederick Brown advertised wool carding at 6-1/4 cents per pound at the old establishment of Mr. Adams, about 2 miles south of New Market, Frederick-Town Herald, May 11, 1831, p. 4. He had offered fulling and dyeing there (Mrs. Adams’), Ibid., August 20, 1825. This was presumably the fulling mill shown on the 1808 Charles Varlé map on Bush Creek, 0.33 mile north of the present Weller Road, SE of Monrovia. The 1860 Bond map showed the Mrs. H. Norris wool factory, while the 1878 atlas showed Mrs. Norris with a grist and sawmill. ADLER ROPEWALK (F) A ropewalk operated by John Adler in 1819 was on South Market Street, Frederick. The building was occupied in 1976 by Federated Charities (See, Ralph F. Martz, “Richard Potts,” Frederick Post, May 11, 1976, p. A-7). ADELSPERGER MILL CO (5) This steam foundry and machine shop was listed in the 1860 census of manufactures with $14,000 capital investment and 25 employees; annual output was $5000 in castings and $25,000 in machinery. ADLUM STILL ( ) John Adlum advertised to sell two stills, 106-gallon and 49-gallon, Frederick-Town Herald, August 14, 1802. AETNA GLASS WORKS (7) Thomas Johnson purchased some of Amelung’s machinery and built a new Aetna Glass Works on Bush Creek, hauling sand from Ellicott City in empty wheat wagons. He later built another works on Tuscarora Creek, The Potomac, p. -

F-7-141 Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area

F-7-141 Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 10-11-2011 CAPSULE SUMMARY Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area MIHJP# F-7-141 Dickerson vicinity Frederick and Montgomery counties, Maryland NRMA=1974 Public The Monocacy Natural Resources Management Area (NRMA) occupies 2,011 acres that includes property along both banks of the lower Monocacy River and most of the Furnace Branch watershed in southeastern Frederick and western Montgomery counties. The area is predominantly rural, comprising farmland and rolling and rocky wooded hills. Monocacy NRMA's main attraction is the Monocacy River, which was designated a Maryland Scenic River in 1974. The NRMA began in 1974 with the acquisition of the 729-acre Rock Hall estate. -

A Summary of Peak Stages Discharges in Maryland, Delaware

I : ' '; Ji" ' UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY · Water Resources Division A SUMMARY OF PEAK STAGES AND DISCHARGES IN MARYLAND, DELAWARE, AND DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FOR FLOOD OF JUNE 1972 by Kenneth R. Taylor Open-File Report Parkville, Maryland 1972 A SUJ1D11ary of Peak Stages and Discharges in Maryland, Delaware, and District of Columbia for Flood of June 1972 by Kenneth R. Taylor • Intense rainfall associated with tropical storm Agnes caused devastating flooding in several states along the Atlantic Seaboard during late June 1972. Storm-related deaths were widespread from Florida to New York, and public and private property damage has been estllna.ted in the billions of dollars. The purpose of this report is to make available to the public as quickly as possible peak-stage and peak-discharge data for streams and rivers in Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia. Detailed analyses of precipitation, flood damages, stage hydrographs, discharge hydrographs, and frequency relations will be presented in a subsequent report. Although the center of the storm passed just offshore from Maryland and Delaware, the most intense rainfall occurred in the Washington, D. c., area and in a band across the central part of Maryland (figure 1). Precipitation totals exceeding 10 inches during the June 21-23 period • were recorded in Baltimore, Carroll, Cecil, Frederick, Harford, Howard, Kent, Montgomery, and Prince Georges Counties, Md., and in the District of Columbia. Storm totals of more than 14 inches were recorded in Baltimore and Carroll Counties. At most stations more than 75 percent of the storm rainfall'occurred on the afternoon and night of June 21 and the morning of June 22 (figure 2). -

Annual Report 2004

Annual Planning Report 2004 FREDERICK COUNTY DIVISION OF PLANNING 12 E. CHURCH STREET WINCHESTER HALL FREDERICK, MARYLAND 21701 www.co.frederick.md.us/planning Table of Contents Page Number Executive Summary 1 Planning Commission Profile 2 Commission’s and Staff Directory 4 Demographic and Development Trends 7 Community Facilities 8 Zoning Administration 10 Comprehensive Planning 12 Land Preservation 20 Mapping and Data Services 22 Publications Available 23 Executive Summary The 2004 Planning Report for Frederick County, Maryland was prepared pursuant to the requirements of Article 66B of the Annotated Code of Maryland and provides a summary of the year’s planning activities and development trends. Project/Activity Highlights for 2004 • Completed update of the Urbana Region Plan, adopted in June 2004. • Continued review and update of New Market Region Plan and initiated work on the Walkersville Region Plan. • Completed County Commissioner Review of the Citizens Zoning Review Committee Final Report and staff began re-write of the Zoning Ordinance Update. • Processed seven farm applications to sell their development rights under the MALPF Program and received 40 applications for the Installment Purchase Program (IPP). • Received State designation of the Carrollton Manor area as an official Rural Legacy Area. • Processed 49 Board of Zoning Appeals cases up from 44 in 2003. • Conducted 684 new and follow-up zoning inspections with the number of zoning complaints down slightly from 2003 to 249 in 2004. • Continued implementation of the streamlined Land Development and Permitting Process. • Continued research on Pipeline Development and Industrial/Commercial Land Inventory. Development and Demographic Highlights • County population increased by 4,023 persons in 2004, the lowest annual increase since 2000. -

BETHESDA BRAC IMPROVEMENTS BETHESDA TROLLEY TRAIL CONNECTIONS and PASSENGER DROP-OFF LOOP a $1,100,000 Grant Proposal to the Of

BETHESDA BRAC IMPROVEMENTS BETHESDA TROLLEY TRAIL CONNECTIONS AND PASSENGER DROP-OFF LOOP A $1,100,000 Grant Proposal to the Office of Economic Adjustment, U.S. Department of Defense Submitted by the Maryland State Highway Administration, Maryland, Department of Transportation October 7, 2011 RE: Federal Register Document 2011-184000: Volume 70, Number 140, July 21, 2011 Notice of Federal Funding Opportunity (FFO) for construction of Transportation Infrastructure Improvements Associated with medical facilities related to recommendations of the 2005 Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission. A. POINT OF CONTACT : Barb Solberg, Division Chief Highway Design Division Office of Highway Development State Highway Administration 707 North Calvert St. Baltimore MD, 21202 410-545-8830 [email protected] B. EXISTING OR PROJECTED TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE ISSUE : • Relocation of Walter Reed The Bethesda Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) improvement projects are intended to mitigate gridlock, improve pedestrian access and safety, and support multi-modal transportation systems around the new federally-mandated Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. One of the most noteworthy moves mandated by the 2005 BRAC law was the closure of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) in Washington, D.C., with the relocation of most of its functions and personnel to the campus of the National Naval Medical Center (NNMC) in Bethesda, Montgomery County, Maryland, establishing the joint service Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC). The intent of consolidating these two premier institutions was to establish the modern “crown jewel” of military medical care and research combining the best of Army, Navy and Air Force practices that could serve the needs of the American military facing new kinds of catastrophic injuries in the era following September 11, 2001. -

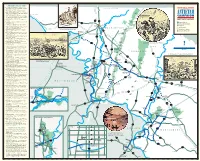

Antietam Map Side

★ ANTIETAM CAMPAIGN SITES★ ★ Leesburg (Loudoun Museum) – Antietam Campaign To ur begins here, where Lee rested the Army of Northern MASON/DIXON LINE Virginia before invading Maryland. ★ Mile Hill – A surprise attack led by Confederate Col. Thomas Munford on Sept. 2, 1862, routed Federal forces. ★ White’s Ferry (C&O Canal NHP) – A major part of Lee’s army forded the Potomac River two miles north of this mod- ern ferry crossing, at White’s Ford. To Cumberland, Md. ★ White’s Ford (C&O Canal NHP) – Here the major part of the Army of Northern Virginia forded the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5-6, 1862, while a Confederate band played “Maryland! My Maryland!” ★ Poolesville – Site of cavalry skirmishes on September 5 & 8, 1862. 81 11 ★ Beallsville – A running cavalry fight passed through town Campaign Driving Route on September 9, 1862. 40 ★ Barnesville – On September 9, 1862, opposing cavalry Alternate Campaign Driving Route units chased each other through town several times. Rose Hill HAGERSTOWN Campaign Site ★ Comus (Mt. Ephraim Crossroads) – Confederate cavalry Cemetery fought a successful rearguard action here, September 9-11, Other Civil War Site 1862, to protect the infantry at Frederick. The German Reformed Church in Keedysville W ASHINGTON ★ Sugarloaf Mountain – At different times, Union and was used as a hospital after the battle. National, State or County Park Confederate signalmen atop the mountain watched the 40 I L InformationInformation or Welcome Center opposing army. Williamsport R A T ★ Monocacy Aqueduct (C&O Canal NHP) – Confederate (C&O Canal NHP) troops tried and failed to destroy or damage the aqueduct South Mountain N on September 4 & 9, 1862. -

FY16-FY21 the City of Frederick Capital Improvements Program

FY16-FY21 The City of Frederick Capital Improvements Program THE CITY OF FREDERICK CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS PROGRAM FY2016-2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Capital Improvement Program FY 2016-2021 SUMMARY SCHEDULE ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 1-3 GENERAL FUND FACILITIES 110007 – DPW Emergency Generator………………………………………………………………………………………….... Page 4-5 120005 – Downtown Hotel Project…………… ……………………………………………………………………………….... Page 6-7 120006 – City Hall Roof Replacement…………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 8-9 120007 – Sustainability Initiatives……………………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 10-11 120009 – New Police Headquarters ……………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 12-13 ROADS 310004 – Monocacy Blvd/Rt 15 Interchange….…………………………………………………………………………………. Page 14-15 310006 – Christophers Crossing Corridor – Ft. Detrick…………………………………………………………………………. Page 16-17 310007 – Christophers Crossing Corridor – Sanner……………………………………………………………………………… Page 18-19 310304 – Monocacy Blvd. – Central Section – Phase II…………………………………………………………………………. Page 20-21 320007 – Opossumtown Pike/TJ Drive Intersection Improvements……………………………………………………………… Page 22-23 320015 – Butterfly Lane Improvements – Realignment…………………………………………………………………………. Page 24-25 320018 – Christophers Crossing Corridor & Intersection Improvements……………………………………………………….. Page 26-27 320024 – Fairview Avenue Full Depth Reconstruction…………………………………………………………………………. Page 28-29 320025 – Rosemont Avenue Full Depth Reconstruction………………………………………………………………………… Page 30-31 320026 – South Carroll Street Full Depth Reconstruction………………………………………………………………………. -

Maryland Historical Trust Inventory No

Capsule Summary Inventory No. F-7-139 Monocacy Crossing Urbana Pike and Monocacy River Frederick County, MD Ca. 1750-present; 1864 Access: Public Monocacy Crossing consists of a collection of road traces and existing roads, a ferry crossing site, fording place and the current steel truss bridge which carries Maryland Route 355 across the Monocacy River. These crossings date from as early as the mid 18 century and continue to the mid 20th century for the bridge that remains in daily use. On the segment of the Monocacy that flows through the battlefield are two fording places that were known as early as the 1730s. One was located just below the mouth of Ballenger Creek and the other a short distance downstream from the present Maryland Route 355 bridge. The Ballenger Creek area ford was used by Confederate forces during the Battle of Monocacy. The other ford is recorded on land plats and the trace of the old road leading to it is still evident on the landscape. Until the 1830s, when the B&O Railroad was constructed, there was ferry service at this upper ford. The battlefield landscape is largely pastoral, with wooded hillsides and fields of hay, corn and wheat, as well as pasture lands for dairy cattle. The Monocacy River bisects the scene. The battlefield is also bisected with 1-270 a busy commuter route to Washington DC, which crosses the Monocacy approximately lA mile south of the historic crossing place. Outside the limit of the battlefield the surrounding landscape is fragmented, lost in places to intense commercial and residential development. -

IMPLEMENTATION PLAN for VARIOUS TMDLS in MARYLAND October 9, 2020

IMPLEMENTATION PLAN FOR VARIOUS TMDLS IN MARYLAND October 9, 2020 MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION IMPLEMENTATION PLAN FOR STATE HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION VARIOUS TMDLS IN MARYLAND F7. Gwynns Falls Watershed ............................................ 78 TABLE OF CONTENTS F8. Jones Falls Watershed ............................................... 85 F9. Liberty Reservoir Watershed...................................... 94 Table of Contents ............................................................................... i F10. Loch Raven and Prettyboy Reservoirs Watersheds .. 102 Implementation Plan for Various TMDLS in Maryland .................... 1 F11. Lower Monocacy River Watershed ........................... 116 A. Water Quality Standards and Designated Uses ....................... 1 F12. Patuxent River Lower Watershed ............................. 125 B. Watershed Assessment Coordination ...................................... 3 F13. Magothy River Watershed ........................................ 134 C. Visual Inspections Targeting MDOT SHA ROW ....................... 4 F14. Mattawoman Creek Watershed ................................. 141 D. Benchmarks and Detailed Costs .............................................. 5 F15. Piscataway Creek Watershed ................................... 150 E. Pollution Reduction Strategies ................................................. 7 F16. Rock Creek Watershed ............................................. 158 E.1. MDOT SHA TMDL Responsibilities .............................. 7 F17. Triadelphia