Irving Howe: a Leftism of Reason

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

Entanglements the Histories of TDR Martin Puchner

M189TDR_11249_ch02 2/16/06 9:25 AM Page 13 Entanglements The Histories of TDR Martin Puchner Taking stock of TDR in 1983, on the occasion of the release of T100, Brooks McNamara mused: “How long TDR will continue to exist is anybody’s guess. As little magazines go it is positively ante- diluvian” (1983:20; T100).1 More than 20 years later, TDR is still alive and kicking. Its 50th anniver- sary is a cause for celebration. The journal’s 50 years of continuous publication provide us with a unique record of the profound changes in the world of theatre and performance that have taken place in the past half-century. To be sure, the record is anything but neutral. TDR has been an engaged and, at times, polemical participant in the debates about performance, and has frequently changed its own modes of engagement. Should TDR represent new and experimental theatres or rather focus its attention on changing methods of analysis such as structuralist or performance stud- ies analysis? Should it primarily record and analyze performance practices or seek to intervene and shape these practices as well? Should it be wedded to an antiacademic and antidisciplinary stance or become the official organ of a new discipline with a tradition and canon of its own? Taking into account the complex ways in which TDR has acted as a kind of participant-observer of the theatre scene, I will offer a layered history, isolating four distinct dimensions: 1. A history of the kinds of theatres and performances represented in the pages of TDR, a history of its objects of analysis; 2. -

The Mind in Motion: Hopper's Women Through Sartre's Existential Freedom

Intercultural Communication Studies XXIV(1) 2015 WANG The Mind in Motion: Hopper’s Women through Sartre’s Existential Freedom Zhenping WANG University of Louisville, USA Abstract: This is a study of the cross-cultural influence of Jean-Paul Sartre on American painter Edward Hopper through an analysis of his women in solitude in his oil paintings, particularly the analysis of the mind in motion of these figures. Jean-Paul Sartre was a twentieth century French existentialist philosopher whose theory of existential freedom is regarded as a positive thought that provides human beings infinite possibilities to hope and to create. His philosophy to search for inner freedom of an individual was delivered to the US mainly through his three lecture visits to New York and other major cities and the translation by Hazel E. Barnes of his Being and Nothingness. Hopper is one of the finest painters of the twentieth-century America. He is a native New Yorker and an artist who is searching for himself through his painting. Hopper’s women figures are usually seated, standing, leaning forward toward the window, and all are looking deep out the window and deep into the sunlight. These women are in their introspection and solitude. These figures are usually posited alone, but they are not depicted as lonely. Being in outward solitude, they are allowed to enjoy the inward freedom to desire, to imagine, and to act. The dreaming, imagining, expecting are indications of women’s desires, which display their interior possibility or individual agency. This paper is an attempt to apply Sartre’s philosophy to see that these women’s individual agency determines their own identity, indicating the mind in motion. -

The Eichmann Polemics: Hannah Arendt and Her Critics

The Eichmann Polemics: Hannah Arendt and Her Critics Michael Ezra Introduction Hannah Arendt, the German Jewish political philosopher who had escaped from a Nazi internment camp, [1] had obtained international fame and recognition in 1951 with her book The Origins of Totalitarianism. [2] Feeling compelled to witness the trial of Adolf Eichmann (‘an obligation I owe my past’), [3] she proposed to the editor of The New Yorker that she report on the prominent Nazi’s trial in Jerusalem. The editor gladly accepted the offer, placing no restrictions on what she wrote. [4] Arendt’s eagerly awaited ‘report’ finally appeared in The New Yorker in five successive issues from 16 February – 16 March 1963. In May 1963 the articles were compiled into a book published by Viking Press, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. During the Second World War, Adolf Eichmann had been the head of Section IV- B-4 in the Nazi SS, overseeing the deportation of the Jews to their deaths. After the war Eichmann escaped to Argentina where he lived under an assumed name. In May 1960, the Israeli Security Service, Mossad, kidnapped Eichmann in Argentina and smuggled him to Jerusalem to stand trial for wartime activities that included ‘causing the killing of millions of Jews’ and ‘crimes against humanity.’ The trial commenced on 11 April 1961 and Eichmann was convicted and hanged on 31 May 1962. Arendt’s Thesis Enormous controversy centered on what Arendt had written about the conduct of the trial, her depiction of Eichmann and her discussion of the role of the Jewish Councils. -

1 Loneliness

9781586487492-1cx_PublicAffairs 6.125 x 9.25 3/15/10 2:50 PM Page 3 ላ 1 ሌ Loneliness Exiled, wandering, dumbfounded by riches, Estranged among strangers, dismayed by the infinite sky, An alien to myself until at last the caste of the last alienation. —Delmore Schwartz, “Abraham” IMMIGRANTS The Jewish encounter with America began with two dozen refugees setting foot in New Amsterdam, the city on the Hudson River soon to be renamed New York, in 1654. No red carpet greeted them. Governor Peter Stuyvesant wished these members of what he called “the deceitful race” and “blasphe- mers of the name of Christ” to leave. He was overruled by the directors at the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam. The newcomers stayed and were soon joined by brethren who established communities in Philadelphia, Newport, Charleston, and Savannah. A hundred or so American Jews fought in the Revolutionary War on behalf of a country unique in history, a country that from its very inception guaranteed the free exercise of religion. In the not-so-distant past, the Jews of Europe had lived at the whim of their hosts, who could—and did— revoke Jews’ residential rights at any time. Jews had been expelled from Vienna in 1670 and from Prague in 1744. They were commonly seen— and saw themselves—as temporary settlers, as tolerated strangers. Resigned to political powerlessness, they learned to dwell in Jewish tradition itself, poet Heinrich Heine said, as a “portable homeland.” George Washington, by contrast, assured the Jews of Newport that the U.S. government, dedi- cated to religious tolerance, “gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.” 3 From “Running Commentary” by Benjamin Balint. -

TOTALITARIANISM and PARTISAN REVIEW Benli

ABSTRACT Title of Document: DIALECTICS OF DISENCHANTMENT: TOTALITARIANISM AND PARTISAN REVIEW Benli Moshe Shechter, Ph.D., 2011 Directed By: Professor Vladimir Tismaneanu, Department of Government and Politics This dissertation takes the literary and culturally modern magazine, Partisan Review (1934-2003), as its case study, specifically recounting its early intellectual history from 1934 to 1941. During this formative period, its contributing editors broke from their initial engagement with political radicalism and extremism to re-embrace the demo-liberalism of America's foundational principles during, and in the wake of, the Second World War. Indeed, Partisan Review 's history is the history of thinking and re-thinking “totalitarianism” as its editors journeyed through the dialectics of disenchantment. Following their early (mis)adventures pursuant of the radical politics of literature, their break in the history of social and political thought, sounding pragmatic calls for an end to ideological fanaticism, was one that then required courage, integrity, and a belief in the moral responsibility of humanity. Intellectuals long affiliated with the journal thus provide us with models of eclectic intellectual life in pursuit of the open society, as does, indeed, the Partisan Review . DIALECTICS OF DISENCHANTMENT: TOTALITARIANISM AND PARTISAN REVIEW. By BENLI MOSHE SHECHTER Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Vladimir Tismaneanu, Chair Professor C. Fred Alford Professor Charles E. Butterworth Professor James M. Glass Professor Roberto Patricio Korzeniewicz © Copyright by Benli M. Shechter 2011 Preface What steered me in the direction of this dissertation topic—beyond my supervisor— was my interest in what seems to be a perennial battle: intellectuals versus anti- intellectuals. -

The Democratization of Cultural Criticism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@CalPoly The Chronicle Review Home Opinion & Ideas The Chronicle Review July 2, 2004 The Democratization of Cultural Criticism By GEORGE COTKIN Wallace Shawn's play The Designated Mourner is in part a lament for the death of serious cultural criticism and intellectual community. Cultural barbarians have vanquished the life of the mind. But the genius of his play is in its refusal to leave unexamined this state of affairs. Not all of what has been lost is to be mourned. The designated mourner gleefully bids adieu to "all that endless posturing, the seriousness, the weightiness" of culture. Recently, the line of true designated mourners pining for the glory days of criticism has grown longer. After praising the high seriousness and sense of purpose of reviewers during the salad days of the Partisan Review, Sven Birkerts, in a recent article in Bookforum, finds that the literary world has been wounded by the "seemingly gratuitous negativity" of many reviews. Without a cohesive sense of community, without a set of high ideals, and with sensationalism and publicity paramount, critics such as Dale Peck are all too eager to resort to the bludgeon in their reviews, Birkerts says. Peck's reputation as a literary hatchet man (see his new collection of published essays, Hatchet Jobs) was canonized when he opened a New Republic review of Rick Moody's The Black Veil: A Memoir With Digressions with the line: "Rick Moody is the worst writer of his generation." If literary criticism is marked by vicious prose and petty bickering, then art criticism exists without firm judgments. -

Arendt on Arendt: Reflecting on the Meaning of the Eichmann Controversy Audrey P

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2015 Arendt on Arendt: Reflecting on the Meaning of the Eichmann Controversy Audrey P. Jaquiss Pomona College Recommended Citation Jaquiss, Audrey P., "Arendt on Arendt: Reflecting on the Meaning of the Eichmann Controversy" (2015). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 135. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/135 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Eichmann Controversy: The American Jewish Response to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts at Pomona College Department of History By Audrey Jaquiss April 17, 2015 Acknowledgements A writer is nothing without her readers. I would like to thank Professor Pey-Yi Chu for her endless support, brilliant mind and challenging pedagogy. This thesis would not be possible without her immense capacity for both kindness and wisdom. I would also like to thank Professor John Seery for his inspiring conversation and for all the laughter he shared with me along the way. This thesis would not be possible without the curiosity and ceaseless joy he has helped me find in my work. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..5 1. Building a Memory Through Controversy……………………………………………25 1. The Stakes of a Memory ……………………………………………………...33 2. The Banality of Evil…………………………………………………...............41 3. -

827-831 Broadway Buildings

DESIGNATION REPORT 827-831 Broadway Buildings Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission 827-831 Broadway Buildings LP-2594 October 31, 2017 DESIGNATION REPORT 827-831 Broadway Buildings LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 827-829 and 831 Broadway LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE These Civil War-era commercial buildings are significant for their associations with prominent artists of the New York School and represent the pivotal era in which post-World War II New York City became the center of the art world. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission 827-831 Broadway Buildings LP-2594 October 31, 2017 827-831 Broadway November 2017 Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission 827-831 Broadway Buildings LP-2594 October 31, 2017 3 of 39 827-831 Broadway Buildings the Greenwich Village Society for Historic 827-829 and 831 Broadway, Manhattan Preservation, the Willem de Kooning Foundation, Victorian Society, Historic Districts Council, Society for the Architecture of the City, and Landmark West. Two representatives of the owner spoke to offer other positions on the designation. No one spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission also received written statements of support from Borough Designation List 502 President Gale Brewer, Senator Brad Hoylman, the LP-2594 Municipal Art Society of New York, and the New York Landmarks Conservancy. Built: 1866-67 Architect: Griffith Thomas Summary Client: Pierre Lorillard III The 827-831 Broadway Buildings are -

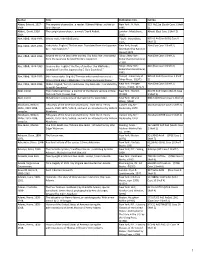

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

827-831 Broadway Buildings

DESIGNATION REPORT 827-831 Broadway Buildings Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission 827-831 Broadway Buildings LP-2594 October 31, 2017 DESIGNATION REPORT 827-831 Broadway Buildings LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 827-829 and 831 Broadway LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE These Civil War-era commercial buildings are significant for their associations with prominent artists of the New York School and represent the pivotal era in which post-World War II New York City became the center of the art world. Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission 827-831 Broadway Buildings LP-2594 October 31, 2017 827-831 Broadway November 2017 Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 502 Commission 827-831 Broadway Buildings LP-2594 October 31, 2017 3 of 39 827-831 Broadway Buildings the Greenwich Village Society for Historic 827-829 and 831 Broadway, Manhattan Preservation, the Willem de Kooning Foundation, Victorian Society, Historic Districts Council, Society for the Architecture of the City, and Landmark West. Two representatives of the owner spoke to offer other positions on the designation. No one spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission also received written statements of support from Borough Designation List 502 President Gale Brewer, Senator Brad Hoylman, the LP-2594 Municipal Art Society of New York, and the New York Landmarks Conservancy. Built: 1866-67 Architect: Griffith Thomas Summary Client: Pierre Lorillard III The 827-831 Broadway Buildings are -

A Critical Study of Changes in Structure, Character, Language, and Theme in Experimental Drama in New York City

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1987 Revolutions Off Off Broadway, 1959-1969: A Critical Study of Changes in Structure, Character, Language, and Theme in Experimental Drama in New York City Alexis Greene Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1789 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy.