TOTALITARIANISM and PARTISAN REVIEW Benli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Finding

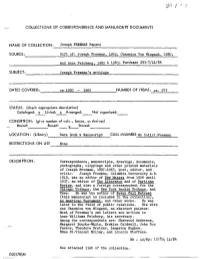

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

Meat: a Novel

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Faculty Publications 2019 Meat: A Novel Sergey Belyaev Boris Pilnyak Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Belyaev, Sergey; Pilnyak, Boris; and LeBlanc, Ronald D., "Meat: A Novel" (2019). Faculty Publications. 650. https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/650 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sergey Belyaev and Boris Pilnyak Meat: A Novel Translated by Ronald D. LeBlanc Table of Contents Acknowledgments . III Note on Translation & Transliteration . IV Meat: A Novel: Text and Context . V Meat: A Novel: Part I . 1 Meat: A Novel: Part II . 56 Meat: A Novel: Part III . 98 Memorandum from the Authors . 157 II Acknowledgments I wish to thank the several friends and colleagues who provided me with assistance, advice, and support during the course of my work on this translation project, especially those who helped me to identify some of the exotic culinary items that are mentioned in the opening section of Part I. They include Lynn Visson, Darra Goldstein, Joyce Toomre, and Viktor Konstantinovich Lanchikov. Valuable translation help with tricky grammatical constructions and idiomatic expressions was provided by Dwight and Liya Roesch, both while they were in Moscow serving as interpreters for the State Department and since their return stateside. -

The Communist Manifesto

The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide These notes are designed to help new comrades to understand some of the basic ideas of Marxism and how they relate to the politics of the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty (AWL). More experienced comrades leading the educationals can use the tutor notes to expand on certain key ideas and to direct comrades to other reading. Paul Hampton September 2006 1 The Communist Manifesto A Study Guide Contents Background to the Manifesto 3 Questions 5 Further reading 6 Title, preface, preamble 7 I: Bourgeois and Proletarians 9 II: Proletarians and Communists 19 III: Socialist and Communist Literature 27 IV: Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Existing Opposition Parties 32 Glossary 35 2 Background to the Manifesto The text Karl Marx wrote the Manifesto of the Communist Party in German. It was first published in February 1848. It has sometimes been misdated 1847, including in Marx and Engels’ own writings, by Kautsky, Lenin and others. The standard English translation was done by Samuel Moore in 1888 and authorised by Frederick Engels. It can be downloaded from the Marxist Internet Archive http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/index.htm There are scores of other editions by different publishers and with other translations. Between 1848 and 1918, the Manifesto was published in more than 35 languages, in some 544 editions, (Beamish 1998 p.233) The text is also in the Marx and Engels Collected Works (MECW), Volume 6, along with other important articles, drafts and reports from the time. http://www.marxists.org.uk/archive/marx/works/cw/volume06/index.htm The context The Communist Manifesto was written for and published by the Communist League, an organisation founded less than a year before it was written. -

Boris Pasternak - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Boris Pasternak - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Boris Pasternak(10 February 1890 - 30 May 1960) Boris Leonidovich Pasternak was a Russian language poet, novelist, and literary translator. In his native Russia, Pasternak's anthology My Sister Life, is one of the most influential collections ever published in the Russian language. Furthermore, Pasternak's theatrical translations of Goethe, Schiller, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, and William Shakespeare remain deeply popular with Russian audiences. Outside Russia, Pasternak is best known for authoring Doctor Zhivago, a novel which spans the last years of Czarist Russia and the earliest days of the Soviet Union. Banned in the USSR, Doctor Zhivago was smuggled to Milan and published in 1957. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature the following year, an event which both humiliated and enraged the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the midst of a massive campaign against him by both the KGB and the Union of Soviet Writers, Pasternak reluctantly agreed to decline the Prize. In his resignation letter to the Nobel Committee, Pasternak stated the reaction of the Soviet State was the only reason for his decision. By the time of his death from lung cancer in 1960, the campaign against Pasternak had severely damaged the international credibility of the U.S.S.R. He remains a major figure in Russian literature to this day. Furthermore, tactics pioneered by Pasternak were later continued, expanded, and refined by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and other Soviet dissidents. <b>Early Life</b> Pasternak was born in Moscow on 10 February, (Gregorian), 1890 (Julian 29 January) into a wealthy Russian Jewish family which had been received into the Russian Orthodox Church. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. For more on the Romanticism and Classicism debate in the maga- zines, see David Goldie’s Critical Difference: T. S. Eliot and John Middleton Murry in English Literary Criticism, 1918–1929 (69– 127). Harding’s discussion in his book on Eliot’s Criterion of the same debate is also worth reviewing, especially his chapter on Murry’s The Adelphi; see 25–43. 2. Esty suggests that the “relativization of England as one culture among many in the face of imperial contraction seems to have entailed a relativization of literature as one aspect of culture . [as] the late modernist generation absorbed the potential energy of a contracting British state and converted it into the language not of aesthetic decline but of cultural revival” (8). In a similar fashion, despite Jason Harding’s claim that Eliot’s periodical had a “self-appointed role as a guardian of European civilization,” his extensive study of the magazine, The “Criterion”: Cultural Politics and Periodical Networks in Inter-War Britain, as the title indicates, takes Criterion’s “networks” to exist exclusively within Britain (6). 3. See Suzanne W. Churchill, The Little Magazine Others and the Renovation of Modern American Poetry; Eric White, Transat- lantic Avant-Gardes: Little Magazines and Localist Modernism; Adam McKible, The Space and Place of Modernism: The Russian Revolution, Little Magazines, and New York; Mark Morrisson, The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audience, and Reception, 1905–1920; Faith Binckes, Modernism, Magazines, and the Avant-Garde: Reading “Rhythm,” 1910–1914. 4. Thompson writes, “Making, because it is a study in an active process, which owes as much to agency as to conditioning. -

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin The idea that socialism could be established in a single country was adopted as an official doctrine by the Soviet Union in 1925, Stalin and Bukharin being the main formulators of the policy. Before this there had been much debate as to whether the only way to secure socialism would be as a result of socialist revolution on a much broader scale, across all Europe or wider still. This book traces the development of ideas about communist utopia from Plato onwards, paying particular attention to debates about universalist ideology versus the possibility for ‘socialism in one country’. The book argues that although the prevailing view is that ‘socialism in one country’ was a sharp break from a long tradition that tended to view socialism as only possible if universal, in fact the territorially confined socialist project had long roots, including in the writings of Marx and Engels. Erik van Ree is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series 1 Liberal Nationalism in 7 The Telengits of Central Europe Southern Siberia Stefan Auer Landscape, religion and knowledge in motion 2 Civil-Military Relations in Agnieszka Halemba Russia and Eastern Europe David J. Betz 8 The Development of Capitalism in Russia 3 The Extreme Nationalist Simon Clarke Threat in Russia The growing influence of 9 Russian Television Today Western Rightist ideas Primetime drama and comedy Thomas Parland -

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St. Petersburg to Chicago Pamphlets Explanatory Power I 6 fDK246.S2 M. Dobrov Chto takoe burzhuaziia? [What is the Bourgeoisie?] Petrograd: Petrogr. Torg. Prom. Soiuz, tip. “Kopeika,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 39 fDK246.S2 S.K. Neslukhovskii Chto takoe sotsializm? [What is Socialism?] Petrograd: K-vo “Svobodnyi put’”, [n.d.] Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 10 fDK246.S2 Aleksandra Kollontai Kto takie sotsial-demokraty i chego oni khotiat’? [Who Are the Social Democrats and What Do They Want?] Petrograd: Izdatel’stvo i sklad “Kniga,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets I 7 fDK246.S2 Vatin (V. A. Bystrianskii) Chto takoe kommuna? (What is a Commune?) Petrograd: Petrogradskogo Soveta Rabochikh i Krasnoarmeiskikh Deputatov, 1918 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 32 fDK246.S2 L. Kin Chto takoe respublika? [What is a Republic?] Petrograd: Revoliutsionnaia biblioteka, 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 31 fDK246.S2 G.K. Kryzhitskii Chto takoe federativnaia respublika? (Rossiiskaia federatsiia) [What is a Federal Republic? (The Russian Federation)] Petrograd: Znamenskaia skoropechatnaia, 1917 1 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E42 fDK246.S2 O.A. Vol’kenshtein (Ol’govich): Federalizm v Rossii [Federalism in Russia] Knigoizdatel’stvo “Luch”, [n.d.] fDK246.S2 E33 I.N. Ignatov Gosudarstvennyi stroi Severo-Amerikanskikh Soedinenykh shtatov: Respublika [The Form of Government of the United States of America: Republic] Moscow: t-vo I. D. Sytina, 1917 fDK246.S2 E34 K. Parchevskii Polozhenie prezidenta v demokraticheskoi respublike [The Position of the President in a Democratic Republic] Petrograd: Rassvet, 1917 fDK246.S2 H35 Prof. V.V. -

The Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research: An

Gregory Alan-Kingman Hom, IS 281 Historical Research Methodology The Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research: An Independent Home for the Left Term paper written for Professor Maack’s class on Historical Research Methodology Introduction/Scope of the Presentation The Southern California Library for Social Studies and Research (SCL) is a library and archive situated in South Central Los Angeles. The SCL has regular presentations of speakers or films on topics relating to the community organizing efforts of Los Angeles activists. The SCL was initially the work of Emil Freed, the son of anarchists and brought up with the consciousness that the world needed to be changed. His political life led him to John Reed Clubs in 1929, which were associated with the Communist Party USA (CPUSA); he eventually became a member of the CPUSA, with which he was associated until his dying days. The library has a diverse collection today. It is in possession of most of the of the run of The California Eagle, one of the West Coast’s oldest African-American newspapers; the papers of labor unions; materials of the Jewish Left in Los Angeles; and materials on the Southern California branch of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense. Quite interesting is that later board members joined the New American Movement (NAM), an organization that attracted those who had left the CPUSA- papers relating to their involvement with that group are included in those later board members’ personal papers. The reality is that historical collections on Chican@s and Latin@s are less well represented, and still less on Asian-Americans. -

Soviet Political Memoirs: a Study in Politics and Literature

SOVIET POLITICAL MEMOIRS: A STUDY IN POLITICS AND LITERATURE by ZOI LAKKAS B.A. HONS, The University of Western Ontario, 1990 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of History) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA June 1992 Zoi Lakkas, 1992 _________________ in presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department. or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. V Department of The University of British &‘olumbia Vancouver, Canada Date 1L4( /1 1q2 DE-6 (2/88) ii ABS TRACT A growing number of Soviet political memoirs have emerged from the former Soviet Union. The main aim of the meinoirists is to give their interpretation of the past. Despite the personal insight that these works provide on Soviet history, Western academics have not studied them in any detail. The principal aim of this paper is to prove Soviet political memoir’s importance as a research tool. The tight link between politics and literature characterizes the nature of Soviet political memoir. All forms of Soviet literature had to reform their brand of writing as the Kremlin’s policies changed from Stalin’s ruthless reign to Gorbachev’s period of openness. -

Generic Experiment and Confusion in Early Canadian Novels of the Great War

Generic Experiment and Confusion in Early Canadian Novels of the Great War Colin Hill he Canadian novel changed dramatically in the years immediately following the Great War of 1914-18. In the 1920s and ’30s an innovative, modern, cosmopolitan, and multi-gen- ericT literary realism began to challenge and supersede the nineteenth- century romanticism that had loomed large in the national fiction at least since Confederation. Two formative literary magazines were found- ed shortly after the 1918 armistice: Canadian Bookman in 1919 and The Canadian Forum in 1920. Both publications printed articles and mani- festos that demanded a new realism capable of representing the modern and independent Canada that had emerged from the war. In these same years, Canadian writers from all regions began to produce modern-real- ist novels in various sub-genres, including prairie realism, urban realism, and social realism. These writers challenged the verbose and ornate styles of their predecessors with a language that was idiomatic and dir- ect. They sought narrative objectivism and impersonality in accordance with the documentary approach they brought to their representations of contemporary Canada. The most ambitious and creative modern realists experimented with literary form and reworked innovative and international modernist devices to express their interest in exploring and representing human psychology. By the end of the 1920s, some of the best examples of these multi-generic modern-realist works had been published, and a few of them are still read today: J.G. Sime’s Sister Woman (1919), Douglas Durkin’s The Magpie (1923), Frederick Philip Grove’s Settlers of the Marsh (1925), Martha Ostenso’s Wild Geese (1925), Morley Callaghan’s Strange Fugitive (1928), and Raymond Knister’s White Narcissus (1929). -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events.