Space Wei Qi—The Launch of Shenzhou V Joan Johnson-Freese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tianwen-1: China's Mars Mission

Tianwen-1: China's Mars Mission drishtiias.com/printpdf/tianwen-1-china-s-mars-mission Why In News China will launch its first Mars Mission - Tianwen-1- in July, 2020. China's previous ‘Yinghuo-1’ Mars mission, which was supported by a Russian spacecraft, had failed after it did not leave the earth's orbit and disintegrated over the Pacific Ocean in 2012. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is also going to launch its own Mars mission in July, the Perseverance which aims to collect Martian samples. Key Points The Tianwen-1 Mission: It will lift off on a Long March 5 rocket, from the Wenchang launch centre. It will carry 13 payloads (seven orbiters and six rovers) that will explore the planet. It is an all-in-one orbiter, lander and rover system. Orbiter: It is a spacecraft designed to orbit a celestial body (astronomical body) without landing on its surface. Lander: It is a strong, lightweight spacecraft structure, consisting of a base and three sides "petals" in the shape of a tetrahedron (pyramid- shaped). It is a protective "shell" that houses the rover and protects it, along with the airbags, from the forces of impact. Rover: It is a planetary surface exploration device designed to move across the solid surface on a planet or other planetary mass celestial bodies. 1/3 Objectives: The mission will be the first to place a ground-penetrating radar on the Martian surface, which will be able to study local geology, as well as rock, ice, and dirt distribution. It will search the martian surface for water, investigate soil characteristics, and study the atmosphere. -

INPE) MCTI Çp ' Acordo Operação Técnica COPERNICUS Entre ESA,AEB E INPE (0026237) SEI 01350.001611/2018-03 / Pg

ORIGINAL N° 1 Copernicus Space Component Technical Operating Arrangement ESA - Brazilian Space Agency and INPE (INPE) MCTI çp ' Acordo Operação Técnica COPERNICUS entre ESA,AEB E INPE (0026237) SEI 01350.001611/2018-03 / pg. 1 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION....................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background....................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Purpose and objectives ..................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Scope................................................................................................................................. 6 1.4 References......................................................................................................................... 6 2 EUROPEAN ACCESS TO BRAZILIAN EO MISSIONS AND CALIBRATION DATA AND PARTNER IN-SITU DATA ............................................................. 7 3 ARRANGEMENT OF TECHNICAL INTERFACES ....................................... 8 3.1 Technical Arrangement Types.......................................................................................... 8 4 INTERNATIONALARCHIVING AND DISSEMINATION CENTRES, MIRRORSITE ................................................................................................ 9 4.1 Invohred Entities............................................................................................................... 9 4.2 INPE Activity -

China's Space Program

China’s Space Program An Introduction China’s Space Program ● Motivations ● Organization ● Programs ○ Satellites ○ Manned Space flight ○ Lunar Exploration Program ○ International Relations ● Summary China’s Space Program Motivations Stated Purpose ● Explore outer space and to enhance understanding of the Earth and the cosmos ● Utilize outer space for peaceful purposes, promote human civilization and social progress, and to benefit the whole of mankind ● Meet the demands of economic development, scientific and technological development, national security and social progress ● Improve the scientific and cultural knowledge of the Chinese people ● Protect China's national rights and interests ● Build up China’s national comprehensive strength National Space Motivations • Preservation of its political system is overriding goal • The CCP prioritizes investments into space technology ○ Establish PRC as an equal among world powers ○ Space for international competition and cooperation ○ Manned spaceflight ● Foster national pride ● Enhance the domestic and international legitimacy of the CCP. ○ Space technology is metric of political legitimacy, national power, and status globally China’s Space Program Organization The China National Space Administration (CNSA) ● The China National Space Administration (CNSA, GuóJiā HángTiān Jú,) ○ National space agency of the People's Republic of China ○ Responsible for the national space program. ■ Planning and development of space activities. The China National Space Administration ● CNSA and China Aerospace -

India and China Space Programs: from Genesis of Space Technologies to Major Space Programs and What That Means for the Internati

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 India And China Space Programs: From Genesis Of Space Technologies To Major Space Programs And What That Means For The Internati Gaurav Bhola University of Central Florida Part of the Political Science Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Bhola, Gaurav, "India And China Space Programs: From Genesis Of Space Technologies To Major Space Programs And What That Means For The Internati" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4109. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4109 INDIA AND CHINA SPACE PROGRAMS: FROM GENESIS OF SPACE TECHNOLOGIES TO MAJOR SPACE PROGRAMS AND WHAT THAT MEANS FOR THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY by GAURAV BHOLA B.S. University of Central Florida, 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Science in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2009 Major Professor: Roger Handberg © 2009 Gaurav Bhola ii ABSTRACT The Indian and Chinese space programs have evolved into technologically advanced vehicles of national prestige and international competition for developed nations. The programs continue to evolve with impetus that India and China will have the same space capabilities as the United States with in the coming years. -

View Pdf for Soviet Space Culture

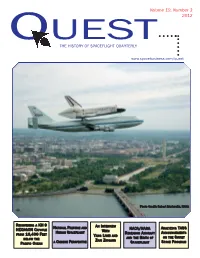

Volume 19, Number 3 2012 OUEST THE HISTORY OF SPACEFLIGHT QUARTERLY www.spacebusiness.com/quest Photo Credit: Robert Markowitz, NASA RECOVERING A KH-99 AN INTERVIEW NATIONAL PRESTIGE AND NACA/NASA ANALYZING TASS HEXAGON CAPSULE WITH HUMAN SPACEFLIGHT RESEARCH AIRCRAFT ANNOUNCEMENTS FROM 16,400 FEET YANG LIWEI AND AND THE BIRTH OF ON THE SOVIET BELOW THE HAI HIGANG A CHINESE PERSPECTIVE Z Z SPACE PROGRAM PACIFIC OCEAN SPACEFLIGHT Contents Volume 19 • Number 3 2012 www.spacebusiness.com/quest 4 An Underwater Ice Station Zebra More Reviews Recovering a KH-99 HEXAGON Capsule from 16,400 Feet Below the Pacific Ocean 64 Into the Blue: American Writing on Aviation and Spaceflight By David W. Waltrop Edited by Joseph J. Corn 18 National Prestige and Human Spaceflight Review by Dominick A. Pisano A Chinese Perspective 65 Destination Mars: By Liang Yang New Explorations of the Red Planet Book by Rod Pyle 31 China’s Great Leap into Space Review by Bob Craddock An Interview with Yang Liwei and Zhai Zhigang By John Vause 66 Soviet Space Culture Cosmic Enthusiasm in Socialist Societies 36 NACA/NASA Research Aircraft and the Edited by Maurer, Richers, Rüthers, and Scheide Review by Michael J. Neufeld Birth of Spaceflight By Curtis Peebles 67 The Space Shuttle: Celebrating Thirty Years of NASA’s First Space Plane Managing the News: 44 Book by Piers Bizony Analyzing TASS Announcements on the Review by Roger D. Launius Soviet Space Program (1957-11964) By Bart Hendrickx 68 The Astronaut: Cultural Mythology and Idealised Masculinity Book Reviews Book by Dario Llinares Review by Amy E. -

Exploration of Mars by the European Space Agency 1

Exploration of Mars by the European Space Agency Alejandro Cardesín ESA Science Operations Mars Express, ExoMars 2016 IAC Winter School, November 20161 Credit: MEX/HRSC History of Missions to Mars Mars Exploration nowadays… 2000‐2010 2011 2013/14 2016 2018 2020 future … Mars Express MAVEN (ESA) TGO Future ESA (ESA- Studies… RUSSIA) Odyssey MRO Mars Phobos- Sample Grunt Return? (RUSSIA) MOM Schiaparelli ExoMars 2020 Phoenix (ESA-RUSSIA) Opportunity MSL Curiosity Mars Insight 2020 Spirit The data/information contained herein has been reviewed and approved for release by JPL Export Administration on the basis that this document contains no export‐controlled information. Mars Express 2003-2016 … First European Mission to orbit another Planet! First mission of the “Rosetta family” Up and running since 2003 Credit: MEX/HRSC First European Mission to orbit another Planet First European attempt to land on another Planet Original mission concept Credit: MEX/HRSC December 2003: Mars Express Lander Release and Orbit Insertion Collission trajectory Bye bye Beagle 2! Last picture Lander after release, release taken by VMC camera Insertion 19/12/2003 8:33 trajectory Credit: MEX/HRSC Beagle 2 was found in January 2015 ! Only 6km away from landing site OK Open petals indicate soft landing OK Antenna remained covered Lessons learned: comms at all time! Credit: MEX/HRSC Mars Express: so many missions at once Mars Mission Phobos Mission Relay Mission Credit: MEX/HRSC Mars Express science investigations Martian Moons: Phobos & Deimos: Ionosphere, surface, -

Master Thesis

Master’s Thesis 2018 30 ECTS Department of International Environment and Development Studies Katharina Glaab Dividing Heaven: Investigating the Influence of the U.S. Ban on Cooperation with China on the Development of Global Outer Space Governance Robert Ronci International Relations LANDSAM The Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, is the international gateway for the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU). Established in 1986, Noragric’s contribution to international development lies in the interface between research, education (Bachelor, Master and PhD programmes) and assignments. The Noragric Master’s theses are the final theses submitted by students in order to fulfil the requirements under the Noragric Master’s programmes ‘International Environmental Studies’, ‘International Development Studies’ and ‘International Relations’. The findings in this thesis do not necessarily reflect the views of Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the author and on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation contact Noragric. © Robert Ronci, May 2018 [email protected] Noragric Department of International Environment and Development Studies The Faculty of Landscape and Society P.O. Box 5003 N-1432 Ås Norway Tel.: +47 67 23 00 00 Internet: https://www.nmbu.no/fakultet/landsam/institutt/noragric i ii Declaration I, Robert Jay Ronci, declare that this thesis is a result of my research investigations and findings. Sources of information other than my own have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. This work has not been previously submitted to any other university for award of any type of academic degree. -

Chang'e 5 Samples (Mexag) (Head-Final)

Chang’E 5 Lunar Sample Return Mission Update James w. Head Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences Brown University Providence, RI 02912 USA Extraterrestrial Materials Analysis Group (ExMAG) Spring Meeting: April 7 - 8, 2021. Extraterrestrial Materials Analysis Group (ExMAG) Spring Meeting Barbara Cohen, ExMAG Chair. 2/10/21 • 1. Please provide an update on the Chang'e 5 Sample Return Mission. • 2. What is known of the collection so far? • 3. Please provide an overview of allocation procedures. • 4. Since US federally-funded researchers cannot work directly with China - Who outside of China is working with the mission team? • 5. We'd also appreciate your thoughts on: What NASA might be able to do to enable the US analysis community to collaborate on this sample collection? Extraterrestrial Materials Analysis Group (ExMAG) Spring Meeting Barbara Cohen, ExMAG Chair. 2/10/21 • 1. Some Myths and Realities. • 2. Organization of the Chinese Space Program. • 3. Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) context for Chang’e 5. • 4. Chang’e 5 Landing Site Selection, Global Context, Key Questions, Mission Operations and Sample Return. • 5. Returned Sample Location, Storage, Preliminary Analysis and Distribution. • 6. Opportunities for International Cooperation. Extraterrestrial Materials Analysis Group (ExMAG) Spring Meeting Barbara Cohen, ExMAG Chair. 2/10/21 • 1. Some Myths and Realities. • 2. Organization of the Chinese Space Program. • 3. Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) context for Chang’e 5. • 4. Chang’e 5 Landing Site Selection, Global Context, Key Questions, Mission Operations and Sample Return. • 5. Returned Sample Location, Storage, Preliminary Analysis and Distribution. • 6. Opportunities for International Cooperation. -

A Pictorial History of Rockets

he mighty space rockets of today are the result A Pictorial Tof more than 2,000 years of invention, experi- mentation, and discovery. First by observation and inspiration and then by methodical research, the History of foundations for modern rocketry were laid. Rockets Building upon the experience of two millennia, new rockets will expand human presence in space back to the Moon and Mars. These new rockets will be versatile. They will support Earth orbital missions, such as the International Space Station, and off- world missions millions of kilometers from home. Already, travel to the stars is possible. Robotic spacecraft are on their way into interstellar space as you read this. Someday, they will be followed by human explorers. Often lost in the shadows of time, early rocket pioneers “pushed the envelope” by creating rocket- propelled devices for land, sea, air, and space. When the scientific principles governing motion were discovered, rockets graduated from toys and novelties to serious devices for commerce, war, travel, and research. This work led to many of the most amazing discoveries of our time. The vignettes that follow provide a small sampling of stories from the history of rockets. They form a rocket time line that includes critical developments and interesting sidelines. In some cases, one story leads to another, and in others, the stories are inter- esting diversions from the path. They portray the inspirations that ultimately led to us taking our first steps into outer space. NASA’s new Space Launch System (SLS), commercial launch systems, and the rockets that follow owe much of their success to the accomplishments presented here. -

February 18, 2015 Dr. Joan Johnson-Freese Professor, Naval War College Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic & Security R

February 18, 2015 Dr. Joan Johnson-Freese Professor, Naval War College Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic & Security Review Commission “China’s Space & Counterspace Programs” The question before the Commission concerns how the United States (U.S.) can achieve stated U.S. goals regarding space security given a rapidly expanding and increasingly sophisticated Chinese space program.1 The importance of protecting the space environment and U.S. space assets in orbit, assets which provide information critical to the U.S. civilian and military sectors and overall U.S. national security, has required that goals be considered and reconsidered at many levels and within multiple communities of the U.S. government. Therefore, it is appropriate to begin by referencing the multiple and nested U.S. strategies related to or referencing space, specifically the 2010 National Security Strategy (NSS), the 2010 National Space Policy (NSP), the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) and the 2011 National Security Space Strategy (NSSS)2 for analytic parameters. Guidance in the NSS is simply stated. “To promote security and stability in space, we will pursue activities consistent with the inherent right of self-defense, deepen cooperation with allies and friends, and work with all nations toward the responsible and peaceful use of space.” (p. 31)3 These general ideas are reiterated in the NSP as “the United States considers the sustainability, stability, and free access to, and use of, space vital to its national interests.” (NSP p.3) With security, sustainability, free-access and stability as overall goals, the NSSS recognizes the importance of working with all space-faring nations due to the nature of the space environment stated as both contested, congested and competitive (NSS p.i) and “… a domain that no nation owns, but on which all rely,” (NSSS p.i). -

The Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2017

Federal Aviation Administration The Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2017 January 2017 Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2017 i Contents About the FAA Office of Commercial Space Transportation The Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA AST) licenses and regulates U.S. commercial space launch and reentry activity, as well as the operation of non-federal launch and reentry sites, as authorized by Executive Order 12465 and Title 51 United States Code, Subtitle V, Chapter 509 (formerly the Commercial Space Launch Act). FAA AST’s mission is to ensure public health and safety and the safety of property while protecting the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States during commercial launch and reentry operations. In addition, FAA AST is directed to encourage, facilitate, and promote commercial space launches and reentries. Additional information concerning commercial space transportation can be found on FAA AST’s website: http://www.faa.gov/go/ast Cover art: Phil Smith, The Tauri Group (2017) Publication produced for FAA AST by The Tauri Group under contract. NOTICE Use of trade names or names of manufacturers in this document does not constitute an official endorsement of such products or manufacturers, either expressed or implied, by the Federal Aviation Administration. ii Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2017 GENERAL CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Introduction 5 Launch Vehicles 9 Launch and Reentry Sites 21 Payloads 35 2016 Launch Events 39 2017 Annual Commercial Space Transportation Forecast 45 Space Transportation Law and Policy 83 Appendices 89 Orbital Launch Vehicle Fact Sheets 100 iii Contents DETAILED CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . -

BACKGROUNDER No

BACKGROUNDER No. 3302 | MARCH 29, 2018 American Missile Defenses and China’s Wayward Space Lab: How Much Danger Does Tiangong-1 Reentry Pose? Dean Cheng Abstract Sometime in spring 2018, the Chinese space station Tiangong-1 will Key Points re-enter the atmosphere. Exactly when—and where—is unclear, and could be dangerous. It is also unclear how much control the Chinese n In the next several weeks, the Chi- have over Tiangong-1. It is possible that Beijing, if unable to control nese space station Tiangong-1 will the spacecraft, would cooperate with the U.S. and other countries in re-enter the atmosphere. Exactly when—and where—is unclear, and mitigating its effects. In that case, the United States and other nations could be dangerous. It is unclear could provide additional space tracking data. If China does not, or how much control the Chinese cannot, provide information about its ability to control the space lab’s have over Tiangong-1. final trajectory, and if it has no national contingency plans on mitigat- n It is possible that Beijing, if unable ing any possible damage, the United States and its partners should to control the spacecraft, would make clear that they will safeguard human life, and also protect their cooperate with the U.S. and other national security. countries in mitigating its effects. China, after all, has been testing ometime in the next several weeks, the Chinese space lab Tian- missile defense capabilities—and Sgong-1 will re-enter the atmosphere. The uncertainty of just Beijing may choose to employ when this 8.5-ton spacecraft will re-enter reflects the remarkable them to break up its space lab.