Paolo Bosisio, Opera Stage Director

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verdi's Rigoletto

Verdi’s Rigoletto - A discographical conspectus by Ralph Moore It is hard if not impossible, to make a representative survey of recordings of Rigoletto, given that there are 200 in the catalogue; I can only compromise by compiling a somewhat arbitrary list comprising of a selection of the best-known and those which appeal to me. For a start, there are thirty or so studio recordings in Italian; I begin with one made in 1927 and 1930, as those made earlier than that are really only for the specialist. I then consider eighteen of the studio versions made since that one. I have not reviewed minor recordings or those which in my estimation do not reach the requisite standard; I freely admit that I cannot countenance those by Sinopoli in 1984, Chailly in 1988, Rahbari in 1991 or Rizzi in 1993 for a combination of reasons, including an aversion to certain singers – for example Gruberova’s shrill squeak of a soprano and what I hear as the bleat in Bruson’s baritone and the forced wobble in Nucci’s – and the existence of a better, earlier version by the same artists (as with the Rudel recording with Milnes, Kraus and Sills caught too late) or lacklustre singing in general from artists of insufficient calibre (Rahbari and Rizzi). Nor can I endorse Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s final recording; whether it was as a result of his sad, terminal illness or the vocal decline which had already set in I cannot say, but it does the memory of him in his prime no favours and he is in any case indifferently partnered. -

Montserrat Caballé En El Teatro De La Zarzuela

MONTSERRAT CABALLÉ EN EL Comedia musical en dos actos TEATRO DE LA ZARZUELA Victor Pagán Estrenada en el Teatro Bretón de los Herreros de Logroño, el 12 de junio de 1947, y en el Teatro Albéniz de Madrid, el 30 de septiembre de 1947 Teatro de la Zarzuela Con la colaboración de ontserrat Caballé M en el Teatro de la Zarzuela1 1964-1992 1964 1967 ANTOLOGÍA DE LA TONADILLA Y LA VIDA BREVE LA TRAVIATA primera temporada oficial de ballet y teatro lírico iv festival de la ópera de madrid 19, 20, 21, 22, 24 de noviembre de 1964 4 de mayo de 1967 Guión de Alfredo Mañas y versión musical de Cristóbal Halffter Música de Giuseppe Verdi Libreto de Francesco Maria Piave, basado en Alexandre Dumas, hijo compañía de género lírico Montserrat Caballé (Violetta Valery) La consulta y La maja limonera (selección) Aldo Bottion (Alfredo Germont), Manuel Ausensi (Giorgio Germont), Textos y música de Fernando Ferrandiere y Pedro Aranaz Ana María Eguizabal (Flora Bervoix), María Santi (Annina), Enrique Suárez (Gastone), Juan Rico (Douphol), Antonio Lagar (Marquese D’Obigny), Silvano Pagliuga (Dottore Grenvil) Mari Carmen Ramírez (soprano), María Trivó (soprano) Ballet de Aurora Pons Coro de la Radiotelevisión Española La vida breve Orquesta Sinfónica Municipal de Valencia Música de Manuel de Falla Dirección musical Carlo Felice Cillario, Alberto Leone Libreto de Carlos Fernández Shaw Dirección de escena José Osuna Alberto Lorca Escenografía Umberto Zimelli, Ercole Sormani Vestuario Cornejo Montserrat Caballé (Salud) Coreografía Aurora Pons Inés Rivadeneira (Abuela), -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

El Bilbao Operístico Llora La Muerte De Corelli Y Bonisolli

38 Bilbao 2003.eko abendua Ambos tenores fueron estrellas distinguidas en los festivales de la A.B.A.O. El Bilbao operístico llora la muerte de Corelli y Bonisolli Carlos Bacigalupe ASI lo quiso el destino. Fue el jue- ves 30 de octubre de este 2003 el d’a en que fallecieron dos figuras de la —pera: Franco Corelli y Fran- co Bonisolli. Claro que hab’a en- tre los dos una sensible diferencia de edades, por cuanto que el pri- mero muri— a los 82 a–os y el se- gundo nos abandonaba apenas cumplidos los 65. Una casualidad. Bonisolli, que siempre envidi— la calidad y la apostura de Corelli, protagoniz— anŽcdotas mil en el curso de su ca- rrea profesional. Fue durante dŽ- cadas el tenor favorito de la —pera de Viena, aunque su debut se pro- dujo en el Festival de Spoleto de Bonisolli, en los momentos previos al escándalo Corelli, junto a Juan Elúa acto dio una lecci—n de bien can- A pesar de todo, el agudo final lo firmado por el cantante para La Curiosamente, ¡quién lo iba tar, aunque a medida que transcu- dio timbrado y con fuerza, pudiŽn- BohŽme e inmediatamente, se rr’a la representaci—n pudo not‡r- dose oir un ÒaddioÓ cercano a lo contrat— a Beniamino Prior para a decir!, los dos fallecieron sele un tanto cansado. Con respec- normal. Hubo gente que comenz— que le sustituyera. La A.B.A.O., to a Otello, Bonisolli hizo lo im- a temerse lo peor. Durante el des- por resumir, no cay— en la trampa el pasado 30 de octubre posible por recrear al personaje. -

La Traviata Stagione D’Opera 2013 / 2014 Giuseppe Verdi La Traviata

G L a i 1 u t r s a e v p i p a e t a V e r d i S t a g i o n e d ’ O p e r a LaGiutsrepapevVeiradi ta 2 0 1 3 / 2 0 1 4 Stagione d’Opera 2013 / 2014 La traviata Melodramma in tre atti Libretto di Francesco Maria Piave Musica di Giuseppe Verdi Nuova produzione Teatro alla Scala EDIZIONI DEL TEATRO ALLA SCALA TEATRO ALLA SCALA PRIMA RAPPRESENTAZIONE Sabato 7 dicembre 2013, ore 18 REPLICHE dicembre Giovedì 12 Ore 20 - Turno D Domenica 15 Ore 20 - Turno B Mercoledì 18 Ore 20 - Turno A Domenica 22 Ore 15 - Turno C Sabato 28 Ore 20 - Turno E Martedì 31 Ore 18 - Fuori abbonamento gennaio Venerdì 3 Ore 20 - Turno N Anteprima dedicata ai Giovani LaScalaUNDER30 Mercoledì 4 dicembre 2013, ore 18 In copertina: La traviata di Giuseppe Verdi. Regia e scene di Dmitri Tcherniakov, costumi di Yelena Zaytseva, luci di Gleb Filshtinsky. Allestimento realizzato per l'inaugurazione della stagione scaligera 2013-14, rendering di una delle scene ideate da Dmitri Tcherniakov. SOMMARIO 5 La traviata. Il libretto 34 Il soggetto Emilio Sala Argument – Synopsis – Die Handlung ––࠶ࡽࡍࡌ Сюжет 46 L’opera in breve Emilio Sala 48 ...la musica Claudio Toscani 53 Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes in terra italina Antonio Rostagno 71 Fisiologia della Traviata Emilio Sala 93 Eros e charitas nella Traviata Paolo Gallarati 131 Un mondo a parte Benedetta Craveri 147 Nota sull’edizione della Traviata Daniele Gatti 149 “Di quell’amor...” (Note di regia) Dmitri Tcherniakov 154 La traviata alla Scala dal 1859 al 2008 Andrea Vitalini 203 Daniele Gatti 205 Dmitri Tcherniakov 206 Gleb Filshtinsky 207 Yelena Zaytseva 208 La traviata. -

Hommage À Giuseppe Verdi

Hommage à Giuseppe Verdi La célébration en 2013 du bicentenaire de la naissance de Giuseppe Verdi est pour nous l’occasion d’offrir aux auditeurs de Cappuccino, que nous remercions de leur fidélité, une sélection des plus beaux extraits de ses opéras les plus célèbres par les interprètes et les chefs les plus prestigieux d’hier et d’aujourd’hui. Verdi ! Que l’on connaisse ce nom illustre ou qu’on l’ignore, on connaît et on fredonne sa musique, la musique d’un homme né en 1813, il y a deux siècles, et mort à Milan en 1901, à la naissance du XXème siècle ! C’est, avec Wagner (qui est né la même année que lui), le plus grand compositeur d’opéra du 19ème siècle. Ce sont les deux très grands, qui ont en commun d’avoir modernisé l’opéra, en lui apportant une puissance dramatique qui lui manquait souvent, et en mettant la voix au service du livret et de l’action. Sans oublier certes Rossini, Bellini et Donizetti, pour ne parler que de l’Italie. Mais il est vrai que l’on retient d’abord les noms de Verdi et Wagner, V et W … Volkswagen ?, les deux géants, ceux dont les noms sont connus du grand public alors que les autres sont un élément de connaissance culturelle. Verdi et Wagner ont dépassé ce stade. Les deux ont joué un rôle d’influence important dans la lutte pour l’unité de la Nation. Mais alors que Wagner cherchait son inspiration poétique dans les fonds de légendes germaniques et dans une volonté d’unité nationale, lui aussi, Verdi s’ouvrait à une inspiration plus européenne, internationale même, personnages espagnols (Don Carlo, Le Trouvère), écossais (Macbeth), français (La Traviata) etc. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE VOCAL TECHNIQUE OF THE VERDI BARITONE JOHN CURRAN CARPENTER SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Music with honors in Music Reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles Youmans Associate Professor of Musicology Thesis Supervisor Mark Ballora Associate Professor of Music Technology Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT I wrote this thesis in an attempt to provide useful information about the vocal technique of great operatic singers, especially “Verdi baritones”—singers specializing in dramatic lead roles of this voice-type in Giuseppe Verdi’s operas. Through careful scrutiny of historical performances by great singers of the past century, I attempt to show that attentive listening can be a vitally important component of a singer’s technical development. This approach is especially valuable within the context of a mentor/apprentice relationship, a centuries-old pedagogical tradition in opera that relies heavily on figurative language to capture the relationship between physical sensation and quality of sound. Using insights gleaned from conversations with my own teacher, the heldentenor Graham Sanders, I analyze selected YouTube clips to demonstrate the relevance of sensitive listening for developing smoothness of tone, maximum resonance, legato, and other related issues. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. -

Verdi Il Trovatore Mp3, Flac, Wma

Verdi Il Trovatore mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Il Trovatore Country: Europe Released: 1986 Style: Opera MP3 version RAR size: 1604 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1693 mb WMA version RAR size: 1468 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 779 Other Formats: ADX ASF RA MP2 AA DXD MOD Tracklist A1 Akt Nr. 1- Nr. 3 A2 Akt Nr. 4 B Akt Nr. 5 - Nr. 8 C1 Akt Nr. 9 - Nr. 11 C2 Akt Nr. 12 Anfang D Akt Nr. 12 Schluß - Nr. 13 - Nr. 14 - Schluß Companies, etc. Recorded At – Walthamstow Assembly Hall Phonographic Copyright (p) – EMI Records Ltd. Pressed By – EMI Electrola GmbH Printed By – 4P Nicolaus GMBH Credits Baritone Vocals [Il Count Di Luna] – Piero Cappuccilli Bass Vocals [Ferrando] – Ruggero Raimondi Bass Vocals [Un Vecchio Zingaro] – Martin Egel Chorus – Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin Chorus Master – Walter Hagen-Groll Composed By – Giuseppe Verdi Conductor – Herbert Von Karajan Engineer [Balance] – Wolfgang Gülich Libretto By – Salvatore Cammarano Liner Notes – Julian Budden, Maurice Tassart Liner Notes [Italian Translation] – Franco Sgrignoli Mezzo-soprano Vocals [Azucena] – Elena Obraztsova Mezzo-soprano Vocals [Inez] – Maria Venuti Orchestra – Berliner Philharmoniker Producer – Michel Glotz Soprano Vocals [Leonora] – Leontyne Price Tenor Vocals [Manrico] – Franco Bonisolli Tenor Vocals [Ruiz] – Horst Nitsche Tenor Vocals [Un Messaggero] – Horst Nitsche Notes Issued with 40-page booklet containing liner notes and libretto in English, German, French and Italian Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side 1 Runout): -

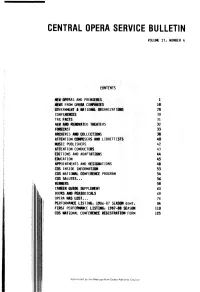

Central Opera Service Bulletin Volume 27, Number 4

CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE BULLETIN VOLUME 27, NUMBER 4 CONTENTS NEK OPERAS AND PREMIERES 1 NEWS FROM OPERA COMPANIES 18 GOVERNMENT ft NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS 28 CONFERENCES 30 TAX FACTS 31 NEtf AND RENOVATED THEATERS 32 FORECAST 33 ARCHIVES AND COLLECTIONS 38 ATTENTION COMPOSERS AND LIBRETTISTS 40 MUSIC PUBLISHERS 42 ATTENTION CONDUCTORS 43 EDITIONS AND ADAPTATIONS 44 EOUCATION 45 APPOINTMENTS AND RESIGNATIONS 48 COS INSIDE INFORMATION 53 COS NATIONAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM 54 COS SALUTES... 56 WINNERS 58 CAREER GUIDE SUPPLEMENT 60 BOOKS AND PERIODICALS 68 OPERA HAS LOST... 76 PERFORMANCE LISTING, 1986-87 SEASON CONT. 84 FIRST PERFORMANCE LISTING. 1987-88 SEASON 110 COS NATIONAL CONFERENCE REGISTRATION FORM 125 Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council !>i>'i'h I it •'••'i1'. • I [! I • ' !lIN., i j f r f, I ;H ,',iK',"! " ', :\\i 1 ." Mi!', ! . ''Iii " ii1 ]• il. ;, [. i .1; inil ' ii\ 1 {''i i I fj i i i11 ,• ; ' ; i ii •> i i«i ;i •: III ,''. •,•!*.', V " ,>{',. ,'| ',|i,\l , I i : I! if-11., I ! '.i ' t*M hlfi •'ir, S'1 , M"-'1'1" ' (.'M " ''! Wl • ' ;,, t Mr '«• I i !> ,n 'I',''!1*! ,1 : I •i . H)-i -Jin ' vt - j'i Hi I !<! :il --iiiAi hi CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE BULLETIN Volume 27, Number 4 Spring/Summer 1987 CONTENTS New Operas and Premieres 1 News from Opera Companies 18 Government & National Organizations 28 Conferences 30 Tax Facts 31 New and Renovated Theaters 32 Forecast 33 Archives and Collections 38 Attention Composers and Librettists 40 Music Publishers 42 Attention Conductors 43 Editions and Adaptations 44 Education 45 Appointments and Resignations 48 COS Inside Information 53 COS National Conference Program 54 COS Salutes.. -

Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana

Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana A survey of the major studio recordings in Italian by Ralph Moore Cavalleria rusticana is the slightly elder brother of another classic, Pagliacci; the two operas are almost invariably paired for an evening’s entertainment and have a great deal in common. Together, “Cav ’n’ Pag” are credited with being in the vanguard of the verismo movement which changed the face of Italian opera for ever. Cavalleria isn’t quite as violent, insofar as Pagliacci culminates in two on-stage murders, whereas the demise of the anti-hero Turiddù, although it is once again the result of a stabbing, occurs off-stage and is announced to that audience via the blood-curdling scream of a horrified spectator, “Hanno ammazzato compare Turiddù!”(“Friend Turiddù’s been murdered!”). It is perhaps, even more melodic and possessed of an even more beautiful Intermezzo than Pagliacci, but both depict the lives of southern Italian “everyday country folk” in the Mezzogiorno going to church, drinking and celebrating, loving and quarrelling – and both have adultery as the spur to the plotline. However, the importance of the soprano and tenor lead roles is reversed: in Pagliacci, Nedda’s personality is fairly sketchily drawn and the focus is more upon Canio as a jealous husband – justifiably as it turns out - whereas in Cavalleria, Santuzza takes central stage. Nor is there a real villain as such in Cavalleria - unless it is Turiddù himself, who seduces and abandons one woman, only to move on to an affair with another, married woman. The preservation of the classical dramatic unities of time, place and action, in combination with ordinariness of the characters and the words they speak, consolidates the opera’s veristic nature. -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>4 GREAT BRITAIN: digital, 1979-2008 In the early 1970s the advent of Anthony Rooley, the Consort of Musicke, Emma Kirkby, Christopher Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music brought a fresh look at repertoire from Dowland to Purcell, Handel, Mozart and eventually Beethoven. Solti recorded with the LPO from 1972 and the National Philharmonic was booked regularly from 1974-84. Also during the 1970s the London Sinfonietta’s surveys of Schönberg and Janá ček were recorded. Ashkenazy’s second career as a conductor centred initially on London, with the Philharmonia from 1977 and the RPO from 1987. Philip Pickett’s New London Consort joined the Florilegium roster in 1985 and Argo’s new look brought in a variety of ensembles in the 1990s. But after an LPO Vaughan Williams cycle was aborted in 1997, Decca’s own UK recordings comprised little more than piano music and recital discs. Outside London, Argo recorded regularly in Cambridge and Oxford. Decca engaged the Welsh National Opera from 1980-96 and the Bournemouth Symphony from 1990-96, but otherwise made little use of regional British orchestras. By the time they raised their performing standards to an acceptable level, Chandos, Hyperion and Naxos had largely replaced the old majors in the market for orchestral sessions. >RV0 VENUES One hundred and seventy different venues were used, eighty-eight in the London area and eighty-two elsewhere in Britain, but only one in ten (those in bold ) hosted thirty or more entries, whilst seventy were only visited once. LONDON AREA ABBEY ROAD STUDIOS , St.John’s Wood, London NW8 (1931), initially restricted to EMI labels, were opened to all from 1968. -

Leontyne Price, Herbert Von Karajan

Leontyne Price Ave Maria mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Ave Maria Country: UK Released: 1961 Style: Opera MP3 version RAR size: 1521 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1815 mb WMA version RAR size: 1109 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 142 Other Formats: MP2 MIDI MP3 MP1 ADX AUD AIFF Tracklist A1 Ave Maria A2 Ave Maria B1 O Holy Night B2 Alleluja, K. 165 Notes Stereo Pressing Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Leontyne Price, von Leontyne Price, CEP 729 Karajan* - Ave Maria Decca CEP 729 UK Unknown von Karajan* (7", EP, Mono) Leontyne Price, Leontyne Price, Herbert SEC 5112 Herbert von von Karajan - Ave Maria Decca SEC 5112 Spain 1962 Karajan (7", EP) Ave Maria (7", EP, VD 1018 Leontyne Price Decca VD 1018 Germany Unknown Mono) Leontyne Price, Leontyne Price, Herbert New CEPM 729 Herbert von von Karajan - Ave Maria Decca CEPM 729 Unknown Zealand Karajan (7", EP, Mono) Leontyne Price, von Leontyne Price, SDGE 80503 Karajan* - Ave Maria Decca SDGE 80503 Spain 1962 von Karajan* (7", Mono) Related Music albums to Ave Maria by Leontyne Price Leontyne Price - A Program Of Song Leontyne Price - Price at the Met Joan Sutherland, Leontyne Price, Renata Tebaldi - Christmas Stars Leontyne Price, Fritz Reiner, Hector Berlioz, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Manuel De Falla - El Amor Brujo / Les Nuits D'Été Leontyne Price, Herbert von Karajan, Karl Münchinger, Wiener Philharmoniker, Stuttgarter Kammerorchester - Weihnachtskonzert Leontyne Price, Herbert von Karajan, Vienna Philharmonic - Christmas Songs Holst - Wiener Philharmoniker, Wiener Staatsopernchor, Herbert Von Karajan - The Planets Verdi - Leontyne Price, Jelena Obraszowa, Piero Cappuccilli, Franco Bonisolli, Ruggero Raimondi, Chor der Deutschen Oper Berlin, Berliner Philharmoniker, Herbert Von Karajan - Le Trouvère Leontyne Price - Madam Butterfly Leontyne Price, André Previn - Leontyne Price - André Previn.