Ancient Civilizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring of the Abrasion Processes (By the Example of Alakol Lake, Republic of Kazakhstan)

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 11, 4164-4174 OPEN ACCESS Monitoring of the Abrasion Processes (by the Example of Alakol Lake, Republic of Kazakhstan) Ainagul Abitbayevaa, Adilet Valeyeva, Kamshat Yegemberdiyevaa, Aizhan Assylbekovab and Aizhan Ryskeldievab aInstitute of Geography, Almaty, KAZAKHSTAN; bAl-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, KAZAKHSTAN ABSTRACT The purpose of the study is to analyze the abrasion processes in the regions of dynamically changing Alakol lakeshores. Using the field method, methods of positioning by the GPS receiver and interpretation of remote sensing data, the authors determined that abrasion processes actively contributed to the formation the modern landscape, causing the occurrence of landslide processes due to trimming coastal cliffs. It influences the dynamic mode of coastline, which currently stands in the sea or in the form of capes in the areas of solid rock, or juts out into the bay with a beach by narrow pebble beaches. The results showed that the lakeshores retreated to 60-100 m (from 1990 to 2015). The suggested method of installation reefs may help to increase bio-productivity, to perform the functions of self-purification of sea water and to reduce the process of destruction of the shores of Alakol lake. KEYWORDS ARTICLE HISTORY Abrasion, relief-forming processes, shores Received 12 May 2016 destruction, lakeside niche, submarine reef Revised 07 June 2016 Accepted 13 June 2016 Introduction Relief, especially its development, plays an important role in assessing the environmental safety of the surrounding space and management of the safe use of natural resources (Schultz, 2015; Velichko & Spasskaya, 2002). This role is reflected in multiple forms of the specific exogenous processes and phenomena changing the shape of the environment (Sharapov, 2013; Ermolaev, 2015). -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

Koshymova Aknur the Role of Oghuzes in the VIII-XIII Centuries In

Koshymova Aknur The role of Oghuzes in the VIII-XIII centuries in the formation of ethno genesis of Turkic peoples ANNOTATION To the dissertation prepared to get PhD degree in “History” – 6D020300 General description of the dissertation. The dissertation paper explores the place of Oghuz in the ethnogenesis of the Turkic peoples in the context of the history of the Kazakhs, Azerbaijanis, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, and Turks. The relevance of the research. The studied problem reflects one of the topical issues that has a peculiar place both in national history and foreign historiography. Due to the antiquity and deep historical roots of the ethnogenetic process of the formation of the late Turkic peoples, the researchers recognized the direct involvement of the Oghuz clans and tribes in the history of the Kazakhs. During the study of the ethnogenesis of a single Turkic people, the process of its formation, development paths and features, you can see how great the role of migration and assimilation processes in the content of ethnic mixing of the autochthonous population and alien tribes, which determined the future ethnic composition, language, culture, and this circumstance allows us to consider this factor as the leading one. Therefore, the history of the Oghuz-speaking peoples who inhabited Central and Asia Minor, the Caucasus, from a modern point of view, must be investigated in close connection with the history of the Kazakh people, which makes it possible to obtain valuable scientific results. The history of the Oghuz originating in the VIII century from the territories of the Mongolian plateau and the northeastern part of modern Kazakhstan, which as a result of mass movements occupied the Syrdarya valley, then the territory of modern Turkmenistan, then Azerbaijan and Anatolia, which led to dramatic changes in ethnic processes in these regions, it is necessary to consider taking into account the historical and genetic continuity. -

Medieval Turkic Nations and Their Image on Nature and Human Being (VI-IX Centuries)

Asian Social Science; Vol. 11, No. 8; 2015 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Medieval Turkic Nations and Their Image on Nature and Human Being (VI-IX Centuries) Galiya Iskakova1, Talas Omarbekov1 & Ahmet Tashagil2 1 Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Faculty of History, Archeology and Ethnology, Kazakhstan 2 Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Faculty of Science, Turkey Correspondence: Galiya Iskakova, al-Farabi Avenue, 71, Almaty, 050038, Kazakhstan. Received: November 27, 2014 Accepted: December 10, 2014 Online Published: March 20, 2015 doi:10.5539/ass.v11n8p155 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v11n8p155 Abstract The article aims to consider world vision of medieval (VI-IX centuries) Turkic tribes on nature and human being and the issues, which impact on the emergence of their world image on nature, human being as well as their perceptions in this case. In this regard, the paper analyzes the concepts on territory, borders and bound in the Turks` society, the indicator of the boundaries for Turkic tribes and the way of expression the world concept on nature and human being of above stated nations. The research findings show that Turks as their descendants Kazakhs had a distinctive vision on environment and the relationship between human being and nature. Human being and nature were conceived as a single organism. Relationship of Turkic mythic outlook with real historical tradition and a particular geographical location captures the scale of the era of the birth of new cultural schemes. It was reflected in the various historical monuments, which characterizes the Turkic civilization as a complex system. -

Central Asia: Confronting Independence

THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY UNLOCKING THE ASSETS: ENERGY AND THE FUTURE OF CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS CENTRAL ASIA: CONFRONTING INDEPENDENCE MARTHA BRILL OLCOTT SENIOR RESEARCH ASSOCIATE CARNEGIE ENDOWMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL PEACE PREPARED IN CONJUNCTION WITH AN ENERGY STUDY BY THE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL POLITICAL ECONOMY AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY RICE UNIVERSITY – APRIL 1998 CENTRAL ASIA: CONFRONTING INDEPENDENCE Introduction After the euphoria of gaining independence settles down, the elites of each new sovereign country inevitably stumble upon the challenges of building a viable state. The inexperienced governments soon venture into unfamiliar territory when they have to formulate foreign policy or when they try to forge beneficial economic ties with foreign investors. What often proves especially difficult is the process of redefining the new country's relationship with its old colonial ruler or federation partners. In addition to these often-encountered hurdles, the newly independent states of Central Asia-- Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan-- have faced a host of particular challenges. Some of these emanate from the Soviet legacy, others--from the ethnic and social fabric of each individual polity. Yet another group stems from the peculiarities of intra- regional dynamics. Finally, the fledgling states have been struggling to step out of their traditional isolation and build relations with states outside of their neighborhood. This paper seeks to offer an overview of all the challenges that the Central Asian countries have confronted in the process of consolidating their sovereignty. The Soviet Legacy and the Ensuing Internal Challenges What best distinguishes the birth of the Central Asian states from that of any other sovereign country is the incredible weakness of pro-independence movements throughout the region. -

Ecosystem Service Assessment of the Ili Delta, Kazakhstan Niels Thevs

Ecosystem service assessment of the Ili Delta, Kazakhstan Niels Thevs, Volker Beckmann, Sabir Nurtazin, Ruslan Salmuzauli, Azim Baibaysov, Altyn Akimalieva, Elisabeth A. A. Baranoeski, Thea L. Schäpe, Helena Röttgers, Nikita Tychkov 1. Territorial and geographical location Ili Delta, Kazakhstan Almatinskaya Oblast (province), Bakanas Rayon (county) The Ili Delta is part of the Ramsar Site Ile River Delta and South Lake Balkhash Ramsar Site 2. Natural and geographic data Basic geographical data: location between 45° N and 46° N as well as 74° E and 75.5° E. Fig. 1: Map of the Ili-Balkhash Basin (Imentai et al., 2015). Natural areas: The Ramsar Site Ile River Delta and South Lake Balkhash Ramsar Site comprises wetlands and meadow vegetation (the modern delta), ancient river terraces that now harbour Saxaul and Tamarx shrub vegetation, and the southern coast line of the western part of Lake Balkhash. Most ecosystem services can be attributed to the wetlands and meadow vegetation. Therefore, this study focusses on the modern delta with its wetlands and meadows. During this study, a land cover map was created through classification of Rapid Eye Satellite images from the year 2014. The land cover classes relevant for this study were: water bodies in the delta, dense reed (total vegetation more than 70%), and open reed and shrub vegetation (vegetation cover of reed 20- 70% and vegetation cover of shrubs and trees more than 70%). The land cover class dense reed was further split into submerged dense reed and non-submerged dense reed by applying a threshold to the short wave infrared channel of a Landsat satellite image from 4 April 2015. -

From the Editorial Board

https://doi.org/10.7592/FEJF2019.76.kazakh FROM THE EDITORIAL BOARD KAZAKH DIASPORA IN KYRGYZSTAN: HISTORY OF SETTLEMENT AND ETHNOGRAPHIC PECULIARITIES Bibiziya Kalshabayeva Professor, Department of History, Archeology and Ethnology Al-Farabi Kazakh National University Almaty, Kazakhstan Email: [email protected] Gulnara Dadabayeva Associate Professor, KIMEP University Almaty, Kazakhstan Email: [email protected] Dauren Eskekbaev Associate Professor, Almaty University of Management Almaty, Kazakhstan Email: [email protected] Abstract: The article focuses on the most significant stages of the formation of the Kazakh diaspora in the Kyrgyz Republic, to point out what reasons contributed to the rugged Kazakh migration process in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and how it affected the forms and types of their settlements (compact or disperse). The researched issues also include the identification of factors provoked by humans and the state to launch these migrations. Surprisingly enough, opposite to the claims made by independent Kazakhstan leadership in the early 2000s, the number of Kazakhs in Kyrgyzstan wishing to become repatriates to their native country is still far from the desired. Thus the article is an attempt to find out what reasons and factors influence the Kazakh residents’ desire to stay in the neighboring country as a minority. To provide the answer, the authors analyzed the dynamics of statistical variations in the number of migrants and the reasons of these changes. The other key point in tracing what characteristic features separate Kazakhs in Kyrgyzstan and their kinsmen in Kazakhstan is the archival data, statistical, historical, and field sources, which provide a systematic overview of the largely unstudied pages of the history of the Kazakh diaspora. -

A Handbook of Siberia and Arctic Russia : Volume 1 : General

Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 I. D. 1207 »k.<i. 57182 g A HANDBOOK OF**' SIBERIA AND ARCTIC RUSSIA Volume I GENERAL 57182 Compiled by the Geographical Section of the Naval Intelligence Division, Naval Staff, Admiralty LONDON : PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any Bookseller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses : Imperial House, Kingswav, London, W.C. 2, and 28 1 Abingdon Street, London, S. W. ; 37 Peter Street, Manchester ; 1 St. Andrew's Crescent, Cardiff ; 23 Forth Street, Edinburgh ; or from E. PONSONBY, Ltd., 116 Grafton Street, Dublin. Price 7s. 6d. net Printed under the authority of His Majesty's Stationery Office By Frederick Hall at the University Press, Oxford. NOTE The region covered in this Handbook includes besides Liberia proper, that part of European Russia, excluding Finland, which drains to the Arctic Ocean, and the northern part of the Central Asian steppes. The administrative boundaries of Siberia against European Russia and the Steppe provinces have been ignored, except in certain statistical matter, because they follow arbitrary lines through some of the most densely populated parts of Asiatic Russia. The present volume deals with general matters. The two succeeding volumes deal in detail respectively with western Siberia, including Arctic Russia, and eastern Siberia. Recent information about Siberia, even before the outbreak of war, was difficult to obtain. Of the remoter parts little is known. The volumes are as complete as possible up to 1914 and a few changes since that date have been noted. -

Download From

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2006-2008 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8 th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9 th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 7, 2 nd edition, as amended by COP9 Resolution IX.1 Annex B). A 3 rd edition of the Handbook, incorporating these amendments, is in preparation and will be available in 2006. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY . Yerokhov Sergei, Tursunvbayev Valentin. DD MM YY E-mail: [email protected] Sergey Yerokhov Turgut Ozal Str. 242, Ap.1 050046. Almaty, Kazakhstan Designation Site Reference Number Phone: + + 727 3920962 (home) E-mail: [email protected] 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: October –November, 2007 3. -

Zhanat Kundakbayeva the HISTORY of KAZAKHSTAN FROM

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN THE AL-FARABI KAZAKH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Zhanat Kundakbayeva THE HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO PRESENT TIME VOLUME I FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO 1991 Almaty "Кazakh University" 2016 ББК 63.2 (3) К 88 Recommended for publication by Academic Council of the al-Faraby Kazakh National University’s History, Ethnology and Archeology Faculty and the decision of the Editorial-Publishing Council R e v i e w e r s: doctor of historical sciences, professor G.Habizhanova, doctor of historical sciences, B. Zhanguttin, doctor of historical sciences, professor K. Alimgazinov Kundakbayeva Zh. K 88 The History of Kazakhstan from the Earliest Period to Present time. Volume I: from Earliest period to 1991. Textbook. – Almaty: "Кazakh University", 2016. - &&&& p. ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 In first volume of the History of Kazakhstan for the students of non-historical specialties has been provided extensive materials on the history of present-day territory of Kazakhstan from the earliest period to 1991. Here found their reflection both recent developments on Kazakhstan history studies, primary sources evidences, teaching materials, control questions that help students understand better the course. Many of the disputable issues of the times are given in the historiographical view. The textbook is designed for students, teachers, undergraduates, and all, who are interested in the history of the Kazakhstan. ББК 63.3(5Каз)я72 ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 © Kundakbayeva Zhanat, 2016 © al-Faraby KazNU, 2016 INTRODUCTION Данное учебное пособие is intended to be a generally understandable and clearly organized outline of historical processes taken place on the present day territory of Kazakhstan since pre-historic time. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

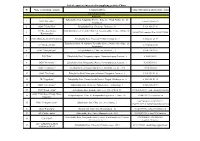

List of Exporters Interested in Supplying Grain to China

List of exporters interested in supplying grain to China № Name of exporting company Company address Contact Infromation (phone num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed Zabaykalsky Krai, Kalgansky District, Bura 1st , Vitaly Kozlov str., 25 1 OOO ''Burinskoe'' [email protected]. building A 2 OOO ''Zelenyi List'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Butina str., 93 8-914-469-64-44 AO "Breeding factory Zabaikalskiy Krai, Chernyshevskiy area, Komsomolskoe village, Oktober str. 3 [email protected] Тел.:89243788800 "Komsomolets" 30 4 OOO «Bukachachinsky Izvestyank» Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Verkholenskaya str., 4 8(3022) 23-21-54 Zabaykalsky Krai, Alexandrovo-Zavodsky district,. Mankechur village, ul. 5 SZ "Mankechursky" 8(30240)4-62-41 Tsentralnaya 6 OOO "Zabaykalagro" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Gaidar str., 13 8-914-120-29-18 7 PSK ''Pole'' Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky region, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 8 OOO "Mysovaya" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Novotsuruhaytuy, Lazo str., 1 8(30243)30111 9 OOO "Urulyungui" Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky District, Dosatuy,Lenin str., 19 B 89245108820 10 OOO "Xin Jiang" Zabaykalsky Krai,Urban-type settlement Priargunsk, Lenin str., 2 8-914-504-53-38 11 PK "Baygulsky" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chernyshevsky District, Baygul, Shkolnaya str., 6 8(3026) 56-51-35 12 ООО "ForceExport" Zabaykalsky Krai, Chita city, Polzunova str. , 30 building, 7 8-924-388-67-74 13 ООО "Eсospectrum" Zabaykalsky Krai, Aginsky district, str. 30 let Pobedi, 11 8-914-461-28-74 [email protected] OOO "Chitinskaya