The Big Switch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

Case 4:13-md-02420-YGR Document 2321 Filed 05/16/18 Page 1 of 74 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 OAKLAND DIVISION 11 IN RE: LITHIUM ION BATTERIES Case No. 13-md-02420-YGR ANTITRUST LITIGATION 12 MDL No. 2420 13 FINAL JUDGMENT OF DISMISSAL This Document Relates To: WITH PREJUDICE AS TO LG CHEM 14 DEFENDANTS ALL DIRECT PURCHASER ACTIONS 15 AS MODIFIED BY THE COURT 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 FINAL JUDGMENT OF DISMISSAL WITH PREJUDICE AS TO LG CHEM DEFENDANTS— Case No. 13-md-02420-YGR Case 4:13-md-02420-YGR Document 2321 Filed 05/16/18 Page 2 of 74 1 This matter has come before the Court to determine whether there is any cause why this 2 Court should not approve the settlement between Direct Purchaser Plaintiffs (“Plaintiffs”) and 3 Defendants LG Chem, Ltd. and LG Chem America, Inc. (together “LG Chem”), set forth in the 4 parties’ settlement agreement dated October 2, 2017, in the above-captioned litigation. The Court, 5 after carefully considering all papers filed and proceedings held herein and otherwise being fully 6 informed, has determined (1) that the settlement agreement should be approved, and (2) that there 7 is no just reason for delay of the entry of this Judgment approving the settlement agreement. 8 Accordingly, the Court directs entry of Judgment which shall constitute a final adjudication of this 9 case on the merits as to the parties to the settlement agreement. -

Confidential

CONFIDENTIAL HEWLETT-PACKARD COMPANY AND SUBSIDIARIES Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements (Continued) Note 18: Segment Information (Continued) management and outsourcing services that support customers’ infrastructure, applications, business processes, end user workplace, print environment and business continuity and recovery requirements. EDS was added as a business unit within HP Services for financial reporting purposes in the fourth quarter of 2008. EDS provides information technology, applications and business process outsourcing services to customers. • HP Software provides enterprise IT management software solutions, including support, that allow customers to manage and automate their IT infrastructure, operations, applications, IT services and business processes under the HP Business Technology Optimization (‘‘BTO’’) brand. The portfolio of BTO solutions also includes tools to automate data center operations and IT processes. HP Software also provides OpenCall solutions, a suite of comprehensive, carrier-grade software platforms for service providers products that enable them to develop and deploy next-generation voice, data and converged network services. HP Software further provides information management and business intelligence solutions, which include enterprise data warehousing, information business continuity, data availability, compliance and e-discovery products that enable our customers to extract more value from their structured and unstructured data and information. HP’s other business segments are described -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

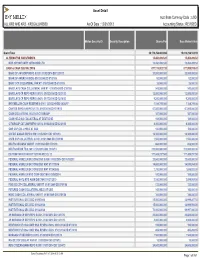

Asset Detail Acct Base Currency Code : USD ALL KR2 and KR3 - KR2GALLKRS00 As of Date : 12/31/2013 Accounting Status : REVISED

Asset Detail Acct Base Currency Code : USD ALL KR2 AND KR3 - KR2GALLKRS00 As Of Date : 12/31/2013 Accounting Status : REVISED . Mellon Security ID Security Description Shares/Par Base Market Value Grand Total 36,179,254,463.894 15,610,214,163.19 ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS 15,450,499.520 15,450,499.52 MKP OPPORTUNITY OFFSHORE LTD 15,450,499.520 15,450,499.52 CASH & CASH EQUIVALENTS 877,174,023.720 877,959,915.42 BANC OF AM CORP REPO 0.010% 01/02/2014 DD 12/31/13 20,000,000.000 20,000,000.00 BANK OF AMERICA (BOA) 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 52,000.000 52,000.00 BARC CCP COLLATERAL VAR RT 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 28,000.000 28,000.00 BARCLAYS CASH COLLATERAL VAR RT 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 543,000.000 543,000.00 BARCLAYS CP REPO REPO 0.010% 01/02/2014 DD 12/31/13 12,000,000.000 12,000,000.00 BARCLAYS CP REPO REPO 0.040% 01/17/2014 DD 12/18/13 9,200,000.000 9,200,000.00 BNY MELLON CASH RESERVE 0.010% 12/31/2049 DD 06/26/97 1,184,749.080 1,184,749.08 CANTOR REPO A REPO 0.170% 01/02/2014 DD 12/19/13 67,000,000.000 67,000,000.00 CASH COLLATERAL HELD AT CITIGROUP 387,000.000 387,000.00 CASH HELD AS COLLATERAL AT DEUTSCHE 169,000.000 169,000.00 CITIGROUP CAT 2MM REPO 0.010% 01/02/2014 DD 12/31/13 8,300,000.000 8,300,000.00 CME CCP COLL HELD AT GSC 100,000.000 100,000.00 CREDIT SUISSE REPO 0.010% 01/02/2014 DD 12/31/13 16,300,000.000 16,300,000.00 CSFB CCP COLLATERAL 0.010% 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 1,553,000.000 1,553,000.00 DEUTSCHE BANK VAR RT 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 668,000.000 668,000.00 DEUTSCHE BK TD 0.180% 01/02/2014 DD 12/18/13 270,000,000.000 270,000,000.00 -

The Broadcast Flag: Compatible with Copyright Law & Incompatible with Digital Media Consumers

607 THE BROADCAST FLAG: COMPATIBLE WITH COPYRIGHT LAW & INCOMPATIBLE WITH DIGITAL MEDIA CONSUMERS ANDREW W. BAGLEY* & JUSTIN S. BROWN** I. INTRODUCTION Is it illegal to make a high-quality recording of your favorite TV show using your Sony digital video recorder with your Panasonic TV, which you then edit on your Dell computer for use on your Apple iPod? Of course it’s legal, but is it possible to use devices from multiple brands together to accomplish your digital media goal? Yes, well, at least for now. What if the scenario involved high-definition television (“HDTV”) devices? Would the answers be as clear? Not as long as digital-content protection schemes like the Broadcast Flag are implemented. Digital media and Internet connectivity have revolutionized consumer entertainment experiences by offering high-quality portable content.1 Yet these attractive formats also are fueling a copyright infringement onslaught through a proliferation of unauthorized Internet piracy via peer-to-peer (“P2P”) networks.2 As a result, lawmakers,3 administrative agencies,4 and courts5 are confronted * Candidate for J.D., University of Miami School of Law, 2009; M.A. Mass Communication, University of Florida, 2006; B.A. Political Science, University of Florida, 2005; B.S. Public Relations, University of Florida, 2005 ** Assistant Professor of Telecommunication, University of Florida; Ph.D. Mass Communica- tions, The Pennsylvania State University, 2001 1 Andrew Keen, Web 2.0: The Second Generation of the Internet has Arrived. It's Worse Than You Think, WEEKLY STANDARD, Feb. 13, 2006, http://www.weeklystandard.com/ Con- tent/Public/Articles/000/000/006/714fjczq.asp (last visited Jan. -

6709BWOL Webstock

RIDING THE WEB-STOCK ROLLER COASTER Reprinted from the August 12, 2004 issue of BusinessWeek Online. Copyright © 2004 by The McGraw-Hill Companies. This reprint implies no endorsement, either tacit or expressed, of any company, product, service or investment opportunity. RIDING THE WEB-STOCK ROLLER COASTER Our BW Web 20 Index tracks a selection of favorite Net stocks, and this column will help interpret the ups and downs he past month has been rotten Just last week, Forrester Research christening the BW Web 20 Index Tfor Internet investors. Stocks raised its e-commerce forecast, pre- – is intended to help aggressive have been hammered since second- dicting U.S. online sales of $227 bil- investors accept the risk inherent in quarter earnings showed Web out- lion in 2007, up from earlier projec- the Web, but balance it by focusing fits growing pretty much as they had tions of $204 billion. Forrester on “real” companies with solid prod- promised – a change from their habit expects e-commerce in the U.S. to ucts, services, and profits. Every of slightly besting quarterly projec- grow 14% annually through 2010 – month, this column will do more than tions. The carnage has been just as three to four times faster than the track how stocks in our index trade – severe in the Real World Internet economy. Meanwhile, growth in it also will help investors figure out Index, a group of Web stocks we Europe is predicted to average 33% which rallies are sustainable and spot picked in 2002 to help ordinary annually through 2009. the bubblicious behavior that earned investors play the Internet without Net investing a bad rap. -

Software Industry Financial Report Contents

The Software Industry Financial Report SOFTWARE INDUSTRY FINANCIAL REPORT CONTENTS About Software Equity Group Leaders in Software M&A 4 Extensive Global Reach 5 Software Industry Macroeconomics Global GDP 8 U.S. GDP and Unemployment 9 Global IT Spending 10 E-Commerce and Digital Advertising Spend 11 SEG Indices vs. Benchmark Indices 12 Public Software Financial and Valuation Performance The SEG Software Index 14 The SEG Software Index: Financial Performance 15-17 The SEG Software Index: Market Multiples 18-19 The SEG Software Index by Product Category 20 The SEG Software Index by Product Category: Financial Performance 21 The SEG Software Index by Product Category: Market Multiples 22 Public SaaS Company Financial and Valuation Performance The SEG SaaS Index 24 The SEG SaaS Index Detail 25 The SEG SaaS Index: Financial Performance 26-28 The SEG SaaS Index: Market Multiples 29-30 The SEG SaaS Index by Product Category 31 The SEG SaaS Index by Product Category: Financial Performance 32 The SEG SaaS Index by Product Category: Market Multiples 33 Public Internet Company Financial and Valuation Performance The SEG Internet Index 35 The SEG Internet Index: Financial Performance 36-38 The SEG Internet Index: Market Multiples 39-40 The SEG Internet Index by Product Category 41 The SEG Internet Index by Product Category: Financial Performance 42 The SEG Internet Index by Product Category: Market Multiples 43 1 Q3 2013 Software Industry Financial Report Copyright © 2013 by Software Equity Group, LLC All Rights Reserved SOFTWARE INDUSTRY FINANCIAL -

Essay Review

1 Essay review The future of the work we don’t do Jan Nolin Swedish school of Library and information science University of Borås The story of machines replacing manual labor has been a bittersweet iteration ever since the industrial revolution. On the one hand, people have increasingly been spared ugly, hard, repetitive and dangerous tasks. On the other hand, we have continuously lost traditional skills and high-level craftsmanship developed over several generations. Most importantly, every time new technologies safely and cheaply allow one machine to do the work of 20, we fear that we will run out of jobs. Nonetheless, as we have experienced this same pattern again and again we tend to feel confident that we will land on our feet. History has taught us that when old jobs disappear new ones will appear. This cyclic process has perhaps been most pointedly captured with the concept “creative destruction”, suggested by Austrian/American economy researcher Joseph Schumpeter in his book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942). This refers to the pattern of solid market traditions, the bearers of old wealth, regularly being destroyed while fresh fortunes are created with new inventions. Today we are probably only in the beginning of the new industrial revolution that is sometimes talked about as a shift from manual to digital labor. As always, we fear that innovative technology will disrupt the labor market. Although, history teaches us that we should expect growth of new forms of jobs, this time the creative destruction seems to be one on steroids. A new mobile-based app such as Uber can within a few months wreak havoc on the otherwise robust taxi market, leading to strikes in June 2014 in a range of European cities such as London, Paris and Madrid. -

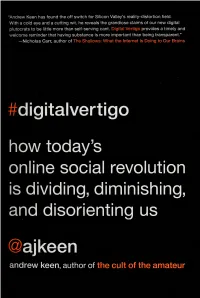

Digital Vertigo Provides a Timely And

"Andrew Keen has found the off switch for Silicon Valley's reality-distortion field. With a cold eye and a cutting wit, he reveals the grandiose claims of our new digital plutocrats to be little more than self-serving cant. Digital Vertigo provides a timely and welcome reminder that having substance is more important than being transparent." -Nicholas Carr, author of The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains #digitalvertigo how today's online social revolution is dividing, diminishing, and disorienting us ajkeen andrew keen, author of the cult of the amateur $25.99/$2< 'Digital Vertigo provides an articulate, measured, rian voice against a sea of hype about auo.ai nnedia. As an avowed technology optii..._ -Larry Downes, author of ishina the Killer does mark zuckerberg know A/hv are we al details of their lives and Google+ ? In Digital Vertigo, Andrew Keen exposes the atest Silicon Valley mania: today's trillion-dollar cr^r-ia| networking revolution online start-up, he reveals—from commerce to communications to entertainment-is now going 3.0." social in a transformation called "Web ^hat he calls this "cult of the socii individual privacy and i jeopardizing both our liberty. Using one of Alfred Hitchcock's greatest films. Vertigo, as his starting point, he argues that social media, with its generation of massive mounts of personal data, is encouraging us to fall in love with something that is too good to be true-a radically transparent twenty-first-century society in which we can all supposedly realize oi"- luthentic identities on the Internet. -

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 13F FORM 13F COVER PAGE Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended: September 30, 2000 Check here if Amendment [ ]; Amendment Number: This Amendment (Check only one.): [ ] is a restatement. [ ] adds new holdings entries Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Name: AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL GROUP, INC. Address: 70 Pine Street New York, New York 10270 Form 13F File Number: 28-219 The Institutional Investment Manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Person Signing this Report on Behalf of Reporting Manager: Name: Edward E. Matthews Title: Vice Chairman -- Investments and Financial Services Phone: (212) 770-7000 Signature, Place, and Date of Signing: /s/ Edward E. Matthews New York, New York November 14, 2000 - ------------------------------- ------------------------ ----------------- (Signature) (City, State) (Date) Report Type (Check only one.): [X] 13F HOLDINGS REPORT. (Check if all holdings of this reporting manager are reported in this report.) [ ] 13F NOTICE. (Check if no holdings reported are in this report, and all holdings are reported in this report and a portion are reported by other reporting manager(s).) [ ] 13F COMBINATION REPORT. (Check -

Annual Report 2008 CEO Letter

Annual Report 2008 CEO letter Dear Fellow Stockholders, Fiscal 2008 was a strong year with some notable HP gained share in key segments, while continuing accomplishments. We have prepared HP to perform to show discipline in our pricing and promotions. well and are building a company that can deliver Software, services, notebooks, blades and storage meaningful value to our customers and stockholders each posted doubledigit revenue growth, for the long term. Looking ahead, it is important to highlighting both our marketleading technology and separate 2008 from 2009, and acknowledge the improved execution. Technology Services showed difficult economic landscape. While we have made particular strength with doubledigit growth in much progress, there is still much work to do. revenue for the year and improved profitability. 2008—Solid Progress and Performance in a Tough The EDS Acquisition—Disciplined Execution of a Environment Multiyear Strategy With the acquisition of Electronic Data Systems In August, HP completed its acquisition of EDS, a Corporation (EDS), we continued implementing a global technology services, outsourcing and multiyear strategy to create the world’s leading consulting leader, for a purchase price of $13 technology company. Additionally, we made solid billion. The EDS integration is at or ahead of the progress on a number of core initiatives, including operational plans we announced in September, and the substantial completion of phase one of HP’s customer response to the acquisition remains very information technology transformation. positive. Fiscal 2008 was also a difficult year, during which The addition of EDS further expands HP’s economic conditions deteriorated. -

US Asian Wire Distribution Points

US Asian Wire Distribution Points NewMediaWire’s comprehensive US Asian Wire delivers your news to targeted media in the Asian American community. Reaches leading Asian−American media outlets and over 375 trades and magazines dealing with political, finance, education, community, lifestyle and legal issues impacting Asian Americans as well as Online databases and websites that feature or cover Asian−American news and issues and The Associated Press. Please note, NewMediaWire includes free distribution to trade publications and newsletters. Because these are unique to each industry, they are not included in the list below. To get your complete NewMediaWire distribution, please contact your NewMediaWire account representative at 310.492.4001. aahar Newspaper Adhra Pradesh Times Newspaper Afternoon Despatch and Courier Newspaper Agence Kampuchea Press Newspaper Akila Daily Newspaper Algorithmica Japonica Newspaper am730 Newspaper Anand Rupwate Newspaper Andhra News Newspaper Andrha Pradesh Times Newspaper ANTARA News Agency Newspaper ASAHI PASOCOM Newspaper ASAHI SHIMBUN Newspaper Asahi Shimbun Newspaper Asahi Shimbun International Satellite Ed Newspaper Asia Insurance Review Newspaper Asia Pacific Management News Newspaper Asia Source Newspaper ASIA TIMES Newspaper Asian Affairs: An American Review Newspaper Asian American Press Newspaper Asian American Times Online Newspaper Asian Enterprise Magazine Newspaper Asian Focus Newspaper Asian Fortune Newspaper Asian Herald Newspaper Asian Industrial Reporter Newspaper Asian Journal Newspaper