Pag En Europa Intro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

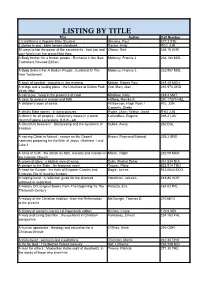

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

What Is an Apostolic Exhortation? It's a Papal Document That Exhorts

‘Evangelii Gaudium’ and ‘Laudato Si’ All creation “groans in travail” (Rom 8:22) How are we called to a deeper conversion? What is an apostolic exhortation? A papal document that encourages the faithful to implement a particular aspect of the Church’s life and teaching. What is an encyclical? A part of the ordinary magisterium (teaching authority) of the Church Evangelii Gaudium (English: The Joy of the Gospel) is a 2013 apostolic exhortation by Pope Francis on "the church's primary mission of evangelization in the modern world." Evangelii Gaudium What is Pope Francis’ main message in Evangelii Gaudium? The principal theme involves the need for a joyful proclamation of the Gospel to the entire world. “…an Apostolic Exhortation written around the theme of Christian joy in order that the Church may rediscover the original source of evangelisation in the contemporary world” In Evangelii Gaudium Pope Francis’ expresses: Concern that the Church is becoming more judgmental than merciful. He wants a Church that has the outgoing spirit of the pilgrim, as opposed to a Church closed in on itself, languishing in ‘institutional inertia’ He worries that some Catholics have become too attached to the external forms of the faith, while their hearts have grown cold. 6 insights provided by Pope Francis, in EG: 1 God’s inexhaustible mercy. 2 The way of beauty. 3 The ‘revolution of tenderness.’ 4 Humility before Scripture. 5 The wounds of Christ. 6 ‘Faith is always a cross.’ God’s inexhaustible mercy. We are called to renew our commitment to mercy as an external work “The Eucharist, although it is the fullness of sacramental life, is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.” The way of beauty. -

The Holy See

The Holy See POST-SYNODAL APOSTOLIC EXHORTATION ECCLESIA IN ASIA OF THE HOLY FATHER JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS, PRIESTS AND DEACONS, MEN AND WOMEN IN THE CONSECRATED LIFE AND ALL THE LAY FAITHFUL ON JESUS CHRIST THE SAVIOUR AND HIS MISSION OF LOVE AND SERVICE IN ASIA: "...THAT THEY MAY HAVE LIFE, AND HAVE IT ABUNDANTLY" (Jn 10:10) INTRODUCTION The Marvel of God's Plan in Asia1. The Church in Asia sings the praises of the "God of salvation" (Ps 68:20) for choosing to initiate his saving plan on Asian soil, through men and women of that continent. It was in fact in Asia that God revealed and fulfilled his saving purpose from the beginning. He guided the patriarchs (cf. Gen 12) and called Moses to lead his people to freedom (cf. Ex 3:10). He spoke to his chosen people through many prophets, judges, kings and valiant women of faith. In "the fullness of time" (Gal 4:4), he sent his only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ the Saviour, who took flesh as an Asian! Exulting in the goodness of the continent's peoples, cultures, and religious vitality, and conscious at the same time of the unique gift of faith which she has received for the good of all, the Church in Asia cannot cease to proclaim: "Give thanks to the Lord for he is good, for his love endures for ever" (Ps 118:1). Because Jesus was born, lived, died and rose from the dead in the Holy Land, that small portion of Western Asia became a land of promise and hope for all mankind. -

Flannery Kevin L., S.J

17_Flannery OK(Gabri)F.qxd:1.Prima Parte 22-08-2007 10:23 Pagina 64 64 YEARBOOK 2004 Flannery Kevin L., S.J. Date and place of birth: 12 August 1950, Cleveland, Ohio, USA Priestly Ordination: 6 June 1987; final vows in the Society of Jesus, 6 June 1999 Appointment to the Academy: 21 February 2004 Scientific discipline: The history of ancient philosophy, ethics Titles: Professor of Philosophy (since 1992); Consultor of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (since 2002) Flannery Academic background Bachelor of Arts (B.A.), English Literature, Ohio State University (Columbus, Ohio), 1972; Master of Arts (M.A.), Anglo-Irish Studies, University College Dublin (Dublin, Ireland), 1974; Master of Arts (M.A.), Philosophy, Politics and Economics (specialization in general philoso- phy and political philosophy), University of Oxford, 1983; Master of Divinity (M.Div.), Weston School of Theology (Cambridge, Massachusetts), 1987; License in Sacred Theology (S.T.L.), Patristics, Weston School of Theology (Cambridge, Massachusetts), 1989; Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.), dissertation: ‘The logic of Alexander of Aphrodisias’, University of Oxford, 1992. Academic positions Professor of the History of Ancient Philosophy at the Pontifical Gregorian University, September 1992 until the present; Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy at the Pontifical Gregorian University, September 1999 to June 2005; Mary Ann Remick Senior Visiting Fellow at the University of Notre Dame Center for Ethics and Culture, 2006-2007; Visiting Scholar, Centre for Philosophical Psychology, Blackfriars, Oxford, Trinity Term, 2007. Summary of scientific research The ethics of Aristotle, with special emphasis on action theory; ancient logic; the ethics of Thomas Aquinas. -

Polish American and Additional Entry Offices

POLONIA CONGRATULATES POLISH PRESIDENTPOLISH IN NEW AMERICAN YORK — JOURNAL PAGE 3 • NOVEMBER 2015 www.polamjournal.com 1 PERIODICAL POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, NEW YORK NEW BOSTON, AT PAID PERIODICAL POSTAGE POLISH AMERICAN OFFICES AND ADDITIONAL ENTRY DEDICATED TO THE PROMOTION AND CONTINUANCE OF POLISH AMERICAN CULTURE JOURNAL REMEMBERING PULASKI AND “THE BIG BURN” ESTABLISHED 1911 NOVEMBER 2015 • VOL. 104, NO. 11 | $2.00 www.polamjournal.com PAGE 16 POLAND MAY SUE AUTHOR GROSS •PASB TILE CAMPAIGN UNVEILING•“JEDLINIOK” TOURS THE EASTERN UNITED STATES HEPI FĘKSGIWYŃG! • A LOOK AT POLAND’S LUTHERANS • FR. MAKA ENLISTS IN NAVY • NOVEMBER HOLIDAYS DO WIDZENIA OR WITAMY AMERIKA? • FATHER LEN’S POLISH CHRISTMAS LEGACY • WIGILIA FAVORITES MADE EASY Newsmark Makes First US Visit Fired Investigator Says US SUPPLY BASES IN POLAND. Warsaw and Washing- House Probe Is Partisan ton have reached agreement on the location of fi ve U.S. WASHINGTON — A The move military supply bases in Poland. The will be established former investigator for the d e - e m - in and around existing Polish military bases Łask, Draws- House Select Committee on phasized ko Pomorskie, Skwierzyna, Ciechanów and Choszczno. PHOTO: RADIO POLSKA Benghazi says he was unlaw- o t h e r Tanks, armored combat vehicles and other military equip- fully fi red in part because he agencies ment will form part of NATO’s quick-reaction spearhead. sought to conduct a compre- involved Siting the storage bases in Poland is expected to facilitate hensive probe into the deadly with the swift mobilization in the event of an attack. The project attacks on the U.S. -

“The Catholic Church Needs Its Own Stonewall” Interview with Krzysztof Charamsa Reconciling Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, Gender Expression and RELIGION

MAGAZINE OF ILGA-EUROPE Destination EQUALITYwinter 2015/16 “The Catholic Church needs its own Stonewall” Interview with Krzysztof Charamsa Reconciling sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and RELIGION LGBT Christians, Muslims and Buddhists speak about their experiences Destination>>EQUALITY winter 2015-2016 1 Krzysztof Charamsa with his partner “The Catholic Church needs its own Stonewall” Interview with Krzysztof Charamsa, a Polish priest and theologian who worked at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in Vatican and who came out as gay in October 2015. Can you tell us what happened after you came out, Krzysztof? What This is the frst moment in my life when I can say “Yes, I am are you doing now, what is your role within the priesthood? free, I am happy!” It is an exciting experience. I am without I am free! I am a freelance priest. You know, in Catholic doctrine, you work, but I am happy. And it feels little contradictory, because I cannot cancel priesthood completely. Once you became a priest, you are a must think about my future, my pension, my security, because priest for life. But you can be suspended; I am in this situation. Objectively I I lost everything. I have no contract any longer. I have been in am a priest – a priest without work, a priest who cannot do his job. the church for 18 years. But now it’s like all those years of my work did not exist for the church, it’s like I am ‘cancelled’. Since I came out, I have been exercising my priesthood in another way; I have had so many contacts with people, with other priests, lay people, I just fnished my book, which I wrote in Italian and Polish, in two young, old. -

Church and State in Rwanda: Catholic Missiology and the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi Marcus Timothy Haworth SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2018 Church and State in Rwanda: Catholic Missiology and the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi Marcus Timothy Haworth SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, African Studies Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Haworth, Marcus Timothy, "Church and State in Rwanda: Catholic Missiology and the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi" (2018). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2830. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2830 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHURCH AND STATE IN RWANDA CATHOLIC MISSIOLOGY AND THE 1994 GENOCIDE AGAINST THE TUTSI MARCUS TIMOTHY HAWORTH WORLD LEARNING – SIT STUDY ABROAD SCHOOL FOR INTERNATIONAL TRAINING RWANDA: POST-GENOCIDE RESTORATION AND PEACEBUILDING PROGRAM CELINE MUKAMURENZI, ACADEMIC DIRECTOR SPRING 2018 ABSTRACT During the 1994 Genocide -

Important Church Writings…

Important Church Writings… Official documents of the Catholic Church have evolved and differentiated over time, but commonly come from four basic sources: 1) Papal documents, issued directly by the Pope under his own name; 2) Church Council documents, issued by ecumenical councils of the Church and now promulgated under the Pope's name, taking the same form as common types of papal documents; and 3) Bishops documents, issued either by individual bishops or by national conferences of bishops. The types of each are briefly explained below. Not all types of documents are necessarily represented currently in this Bibliography. The level of magisterial authority pertaining to each type of document - particularly those of the Pope - is no longer always self- evident. A Church document may (and almost always does) contain statements of different levels of authority commanding different levels of assent, or even observations which do not require assent as such, but still should command the respect of the faithful. The Second Vatican Council, speaking through Lumen Gentium (The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church) identified as many as four different kinds of authority (n. 25). Those affirmations of the Second Vatican Council that recall truths of the faith naturally require the assent of theological faith, not because they were taught by this Council but because they have already been taught infallibly as such by the Church, either by a solemn judgment or by the ordinary and universal Magisterium. So also a full and definitive assent is required for the other doctrines set forth by the Second Vatican Council which have already been proposed by a previous definitive act of the Magisterium. -

Pius Ix and the Change in Papal Authority in the Nineteenth Century

ABSTRACT ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Andrew Paul Dinovo This thesis examines papal authority in the nineteenth century in three sections. The first examines papal issues within the world at large, specifically those that focus on the role of the Church within the political state. The second section concentrates on the authority of Pius IX on the Italian peninsula in the mid-nineteenth century. The third and final section of the thesis focuses on the inevitable loss of the Papal States within the context of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870. Select papal encyclicals from 1859 to 1871 and the official documents of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870 are examined in light of their relevance to the change in the nature of papal authority. Supplementing these changes is a variety of seminal secondary sources from noted papal scholars. Ultimately, this thesis reveals that this change in papal authority became a point of contention within the Church in the twentieth century. ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Andrew Paul Dinovo Miami University Oxford, OH 2004 Advisor____________________________________________ Dr. Sheldon Anderson Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. Wietse de Boer Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. George Vascik Contents Section I: Introduction…………………………………………………………………….1 Section II: Primary Sources……………………………………………………………….5 Section III: Historiography……...………………………………………………………...8 Section IV: Issues of Church and State: Boniface VIII and Unam Sanctam...…………..13 Section V: The Pope in Italy: Political Papal Encyclicals….……………………………20 Section IV: The Loss of the Papal States: The Vatican Council………………...………41 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..55 ii I. -

Academic Statement on the Ethics of Free and Faithful Same-Sex Relationships Table of Contents Foreword Krzysztof Charamsa

Academic Statement on the Ethics of Free and Faithful Same-Sex Relationships Table of Contents Foreword Krzysztof Charamsa Foreword 3 In this time of epoch-making challenge the Academ- was changing, requiring “being” to make room for ic Statement on the Ethics of Free and Faithful Same- “becoming”. The problem of the coexistence of bib- Introduction 8 Sex Relationships offers a powerful intellectual and lical creation with evolutionary development had spiritual manifesto in favour of both non-heterosex- to be resolved, something which is possible, con- 1. Summary of Findings 12 ual people and the community of the Roman Catholic trary to the initial impressions of church authori- 1.1. Some Persons are Non-heterosexual in Orientation Church. Let me reflect on these four elements: time, ties. The ecclesial confrontation with the sciences message, people and the Roman Catholic Church. of evolution was also tortuous: only at the end of 1.2. Papal Teaching the twentieth century did the papacy recognise 1.3. The Biological Argument The time of the epochal challenge that the theory of evolution is more than a scientif- ic hypothesis,2 and therefore a religious faith which 1.4. The Biblical Argument When the Nicolaus Copernicus published De revo- sees itself as in agreement with human reason can- lutionibus orbium cœlestium in 1543, formulating the not avoid integrating its findings. 1.5. Conclusions heliocentric theory, he dethroned Earth and hu- 2. Recommendations 14 mankind from their position at the centre of the The Copernican revolution forced us to change universe and triggered a radical crisis in biblical our understanding of humankind in space; the Dar- 2.1. -

Frigide Barjot; Homophile Malgré Tout?1

JACK D. Frigide Barjot; KIELY homophile malgré tout?1 Jack D. Kiely University College London Abstract Frigide Barjot is the dethroned leader of the Manif pour tous movement that saw hundreds of thousands take to the street to protest against the gay marriage and adoption bill in France from late 2012 onwards. Despite what many claimed to be the self-evident homophobia of the movement, through the denial of equal rights to all, Barjot ferociously maintained and proclaimed her homophilic proclivities, and instead shrouded her arguments against gay marriage and adoption in notions of protection of natural ‘filiation’, the rights of the child and ultimately the promotion of the heterosexual (one man/one woman) family unit above all others. It is through this overt heterosexism, however, that one could perfectly well oppose gay marriage and remain a homophile, or in the least attempt to divest oneself of the charge of homophobia. This paper explores the extent to which this homophilic/homophobic split was maintained by Barjot through the analysis of three of her published works, before, during and after the Manifs pour tous, and the extent to which this split was borne out by other members of the movement, and places this within shifting notions of French republicanism. Keywords: Barjot, Frigide, gay, marriage, homophobia Virginie Tellenne née Merle, ‘stage name’ Frigide Barjot (literally translated as ‘Frigid Bonkers’), is the television star, devout catholic and erstwhile leader of the ‘Manif pour tous’ [‘The Demo for all’] – principal opponent to the proposed ‘Mariage pour tous’ [‘Marriage for all’]2 law of the Hollande government in France – an opposition that saw hundreds of thousands take to the streets to protest against gay marriage and adoption. -

Evangelii Gaudium, Apostolic Exhortation of Pope Francis, 2013 1/14/14 10:17 AM

Evangelii Gaudium, Apostolic Exhortation of Pope Francis, 2013 1/14/14 10:17 AM DOWNLOAD PDF APOSTOLIC EXHORTATION EVANGELII GAUDIUM OF THE HOLY FATHER FRANCIS TO THE BISHOPS, CLERGY, CONSECRATED PERSONS AND THE LAY FAITHFUL ON THE PROCLAMATION OF THE GOSPEL IN TODAY’S WORLD INDEX The joy of the gospel [1] I. A joy ever new, a joy which is shared [2-8] II. The delightful and comforting joy of evangelizing [9-13] Eternal newness [11-13] III. The new evangelization for the transmission of the faith [14-18] The scope and limits of this Exhortation [16-18] CHAPTER ONE THE CHURCH’S MISSIONARY TRANSFORMATION [19] I. A Church which goes forth [20-24] Taking the first step, being involved and supportive, bearing fruit and rejoicing [24] II. Pastoral activity and conversion [25-33] An ecclesial renewal which cannot be deferred [27-33] http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/francesco/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium_en.html Page 1 of 88 Evangelii Gaudium, Apostolic Exhortation of Pope Francis, 2013 1/14/14 10:17 AM III. From the heart of the Gospel [34-39] IV. A mission embodied within human limits [40-45] V. A mother with an open heart [46-49] CHAPTER TWO AMID THE CRISIS OF COMMUNAL COMMITMENT [50-51] I. Some challenges of today’s world [52-75] No to an economy of exclusion [53-54] No to the new idolatry of money [55-56] No to a financial system which rules rather than serves [57-58] No to the inequality which spawns violence [59-60] Some cultural challenges [61-67] Challenges to inculturating the faith [68-70] Challenges from urban cultures [71-75] II.