Federal Regulatory Management of the Automobile in the United States, 1966–1988

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

A Century of Mathematics in America, Peter Duren Et Ai., (Eds.), Vol

Garrett Birkhoff has had a lifelong connection with Harvard mathematics. He was an infant when his father, the famous mathematician G. D. Birkhoff, joined the Harvard faculty. He has had a long academic career at Harvard: A.B. in 1932, Society of Fellows in 1933-1936, and a faculty appointmentfrom 1936 until his retirement in 1981. His research has ranged widely through alge bra, lattice theory, hydrodynamics, differential equations, scientific computing, and history of mathematics. Among his many publications are books on lattice theory and hydrodynamics, and the pioneering textbook A Survey of Modern Algebra, written jointly with S. Mac Lane. He has served as president ofSIAM and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences. Mathematics at Harvard, 1836-1944 GARRETT BIRKHOFF O. OUTLINE As my contribution to the history of mathematics in America, I decided to write a connected account of mathematical activity at Harvard from 1836 (Harvard's bicentennial) to the present day. During that time, many mathe maticians at Harvard have tried to respond constructively to the challenges and opportunities confronting them in a rapidly changing world. This essay reviews what might be called the indigenous period, lasting through World War II, during which most members of the Harvard mathe matical faculty had also studied there. Indeed, as will be explained in §§ 1-3 below, mathematical activity at Harvard was dominated by Benjamin Peirce and his students in the first half of this period. Then, from 1890 until around 1920, while our country was becoming a great power economically, basic mathematical research of high quality, mostly in traditional areas of analysis and theoretical celestial mechanics, was carried on by several faculty members. -

Increased Automobile Fuel Efficiency and Synthetic Fuels: Alternatives for Reducing Oil Imports

Increased Automobile Fuel Efficiency and Synthetic Fuels: Alternatives for Reducing Oil Imports September 1982 NTIS order #PB83-126094 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 82-600603 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Foreword This report presents the findings of an assessment requested by the Senate Com- mittee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. The study assesses and compares increased automobile fuel efficiency and synthetic fuels production with respect to their potential to reduce conventional oil consumption, and their costs and impacts. Con- servation and fuel switching as a means of reducing stationary oil uses are also con- sidered, but in considerably less detail, in order to enable estimates of plausible future oil imports. We are grateful for the assistance of the project advisory panels and the many other people who provided advice, information, and reviews. It should be understood, how- ever, that OTA assumes full responsibility for this report, which does not necessarily represent the views of individual members of the advisory panels. Director Automobile Fuel Efficiency Advisory Panel Michael J. Rabins, Chairman Wayne State University Maudine R. Cooper* John B. Heywood National Urban League, Inc. Massachusetts Institute of Technology John Ferron John Holden National Automobile Dealers Association Ford Motor Co. Donald Friedman Maryann N. Keller Minicar, Inc. Paine, Webber, Mitchell, & Hutchins Herbert Fuhrman Paul Larsen National Institute for GMC Truck and Coach Division Automobile Service Excellence Robert D. Nell James M. Gill Consumers Union The Ethyl Corp. Kenneth Orski R. Eugene Goodson** German Marshall Fund of the United States Hoover Universal, Inc. -

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All Rights Reserved

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All rights reserved. Public Citizen Foundation 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 www.citizen.org ISBN: 978-1-58231-099-2 Doyle Printing, 2016 Printed in the United States of America PUBLIC CITIZEN THE SENTINEL OF DEMOCRACY CONTENTS Preface: The Biggest Get ...................................................................7 Introduction ....................................................................................11 1 Nader’s Raiders for the Lost Democracy....................................... 15 2 Tools for Attack on All Fronts.......................................................29 3 Creating a Healthy Democracy .....................................................43 4 Seeking Justice, Setting Precedents ..............................................61 5 The Race for Auto Safety ..............................................................89 6 Money and Politics: Making Government Accountable ..............113 7 Citizen Safeguards Under Siege: Regulatory Backlash ................155 8 The Phony “Lawsuit Crisis” .........................................................173 9 Saving Your Energy .................................................................... 197 10 Going Global ...............................................................................231 11 The Fifth Branch of Government................................................ 261 Appendix ......................................................................................271 Acknowledgments ........................................................................289 -

Plaintiffs, ) ) V

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CENTER FOR AUTO SAFETY, et al., ) ) Case No. 04-0392 (ESH) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC ) SAFETY ADMINISTRATION, ) ) Defendant. ) ____________________________________) MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO DISMISS This case challenges a de facto legislative rule, promulgated in a 1998 letter to auto manufacturers from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (“NHTSA”), that permits vehicle manufacturers to conduct “regional recalls.” Regional recalls exclude vehicle owners residing in large parts of the country from the warning and free remedy that is guaranteed by the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act (“Safety Act”) to all owners of motor vehicles containing safety-related defects. In its motion to dismiss, NHTSA suggests that plaintiffs Public Citizen and the Center for Auto Safety want to substitute their judgment for that of the agency. To the contrary, through this lawsuit, plaintiffs hope to force NHTSA to comply with Congress’s judgment that safety recalls should protect all motorists, not just those living in select states. NHTSA’s motion falters from the start by mischaracterizing the complaint. Contrary to NHTSA’s repeated statements, plaintiffs are not challenging individual past or future regional recalls. Rather, plaintiffs challenge NHTSA’s across-the-board rule authorizing and setting the standards for regional recalls. The agency’s 1998 letters to auto manufacturers contain specific directives and requirements controlling the conduct of regional recalls, which both bind manufacturers and limit NHTSA’s discretion to take certain actions. Furthermore, plaintiffs have standing to bring this action, as amply illustrated by the complaint, declarations ignored by NHTSA, and additional declarations submitted with this opposition. -

From the Collections of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton, NJ

From the collections of the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton, NJ These documents can only be used for educational and research purposes (“Fair use”) as per U.S. Copyright law (text below). By accessing this file, all users agree that their use falls within fair use as defined by the copyright law. They further agree to request permission of the Princeton University Library (and pay any fees, if applicable) if they plan to publish, broadcast, or otherwise disseminate this material. This includes all forms of electronic distribution. Inquiries about this material can be directed to: Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library 65 Olden Street Princeton, NJ 08540 609-258-6345 609-258-3385 (fax) [email protected] U.S. Copyright law test The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or other reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or other reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. The Princeton Mathematics Community in the 1930s Transcript Number 11 (PMC11) © The Trustees of Princeton University, 1985 MERRILL FLOOD (with ALBERT TUCKER) This is an interview of Merrill Flood in San Francisco on 14 May 1984. The interviewer is Albert Tucker. -

Senator SIMON. Mr. Chairman, If I Could Just Say I Am Going to the Same Press Conference on Health Care

468 Senator SIMON. Mr. Chairman, if I could just say I am going to the same press conference on health care. The CHAIRMAN. One thing Mr. Nader understands is press con- ferences, and I am sure he will understand your need to be there. Senator METZENBAUM. Also, he understands health care. The CHAIRMAN. He understands health care, as well. As a matter of fact, I am surprised he is not going to the press conference with you. Senator COHEN. Mr. Chairman, I am told there is going to be a vote at 1:45 p.m. The CHAIRMAN. I am glad to be informed of all these things. Why don't we just begin and we will see where the schedule takes us. Mr. Nader, welcome. PANEL CONSISTING OF RALPH NADER, WASHINGTON, DC; SID- NEY M. WOLFE, CITIZEN'S GROUP, WASHINGTON, DC; LLOYD CONSTANTINE, CONSTANTINE & ASSOCIATES, NEW YORK, NY; AND RALPH ZESTES, KOGOD COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AD- MINISTRATION, AMERICAN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, DC STATEMENT OF RALPH NADER Mr. NADER. Thank you, Mr. Chairman and members of the com- mittee. I would like to submit my 20-page testimony and note that there are five important attachments: First, one by Professor Carstensen, of the University of Wisconsin Law School, dealing with the case of price squeeze that was so widely discussed earlier in these hear- ings, a case by Judge Breyer; second, a thorough critique by a friend of Judge Breyer, but he is a critic, Professor Tom McGarity, of the University of Texas Law School, on Judge Breyer's health and environmental safety positions; third, a critique of Judge Breyer's chapter on the National Highway Traffic Safety Adminis- tration, by Clarence Ditlow and Joan Claybrook, which illustrates that some of Judge Breyer's research is quite shoddy; fourth, a list of very stimulating questions by Prof. -

The Book Review Column1 by William Gasarch Department of Computer Science University of Maryland at College Park College Park, MD, 20742 Email: [email protected]

The Book Review Column1 by William Gasarch Department of Computer Science University of Maryland at College Park College Park, MD, 20742 email: [email protected] In this column we review the following books. 1. We review four collections of papers by Donald Knuth. There is a large variety of types of papers in all four collections: long, short, published, unpublished, “serious” and “fun”, though the last two categories overlap quite a bit. The titles are self explanatory. (a) Selected Papers on Discrete Mathematics by Donald E. Knuth. Review by Daniel Apon. (b) Selected Papers on Design of Algorithms by Donald E. Knuth. Review by Daniel Apon (c) Selected Papers on Fun & Games by Donald E. Knuth. Review by William Gasarch. (d) Companion to the Papers of Donald Knuth by Donald E. Knuth. Review by William Gasarch. 2. We review jointly four books from the Bolyai Society of Math Studies. The books in this series are usually collections of article in combinatorics that arise from a conference or workshop. This is the case for the four we review. The articles here vary tremendously in terms of length and if they include proofs. Most of the articles are surveys, not original work. The joint review if by William Gasarch. (a) Horizons of Combinatorics (Conference on Combinatorics Edited by Ervin Gyori,¨ Gyula Katona, Laszl´ o´ Lovasz.´ (b) Building Bridges (In honor of Laszl´ o´ Lovasz’s´ 60th birthday-Vol 1) Edited by Martin Grotschel¨ and Gyula Katona. (c) Fete of Combinatorics and Computer Science (In honor of Laszl´ o´ Lovasz’s´ 60th birthday- Vol 2) Edited by Gyula Katona, Alexander Schrijver, and Tamas.´ (d) Erdos˝ Centennial (In honor of Paul Erdos’s˝ 100th birthday) Edited by Laszl´ o´ Lovasz,´ Imre Ruzsa, Vera Sos.´ 3. -

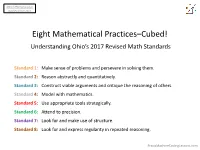

Eight Mathematical Practices–Cubed! Understanding Ohio’S 2017 Revised Math Standards

NWO STEM Symposium Bowling Green 2017 Eight Mathematical Practices–Cubed! Understanding Ohio’s 2017 Revised Math Standards Standard 1: Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Standard 2: Reason abstractly and quantitatively. Standard 3: Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others. Standard 4: Model with mathematics. Standard 5: Use appropriate tools strategically. Standard 6: Attend to precision. Standard 7: Look for and make use of structure. Standard 8: Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning. PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Exploring What’s New in Ohio’s 2017 Revised Math Standards • No Revisions to Math Practice Standards. • Minor Revisions to Grade Level and/or Content Standards. • Revisions Clarify and/or Lighten Required Content. Drill-Down Some Old/New Comparisons… PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Clarify Kindergarten Counting: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Lighten Adding 5th Grade Fractions: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Lighten Solving High School Quadratics: PraxisMachineCodingLessons.com Ohio 2017 Math Practice Standard #1 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Mathematically proficient students start by explaining to themselves the meaning of a problem and looking for entry points to its solution. They analyze givens, constraints, relationships, and goals. They make conjectures about the form and meaning of the solution and plan a solution pathway rather than simply jumping into a solution attempt. They consider analogous problems, and try special cases and simpler forms of the original problem in order to gain insight into its solution. They monitor and evaluate their progress and change course if necessary. Older students might, depending on the context of the problem, transform algebraic expressions or change the viewing window on their graphing calculator to get the information they need. -

The Hamilton Loyalist Published by the Hamilton Branch of the United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada

The Hamilton Loyalist published by the Hamilton Branch of The United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada "They forsook every possession excepting their honour, and set their faces towards the wilderness... to begin, amid untold hardships, life anew under the flag they revered." Vol. X #2 - May 2011 President’s Message It is a particular pleasure to write my first report as your president. We are blessed at Hamilton Branch with one of the most active branches in the entire UEL Association. It is all due to the incredible team who have learned over the years how to get things done and how to stay connected. I am a new-comer and I am constantly amazed at how dedicated your team is. Past President Ruth Nicholson UE, Gloria Oakes UE, Lloyd Oakes UE, and Fred Hayward UE have been so generous with Doug Coppins UE & Pat Blackburn UE received Hamilton advice and help and so patient with me as I attempt to Wentworth Heritage Awards this Spring learn the myriad of details involved in keeping our branch on the straight and narrow. We are blessed at cemeteries from one end of our region to the other with hard-working committees. Last year your and have plans for more. Education Committee members met with over 2300 pupils in schools in our area. Your Cemetery Plaquing I just have to share with you the tremendous Committee carried out plaque unveiling ceremonies advantage we have in our branch in our treasurer Gloria Howard UE and our secretary Marilyn Hardsand UE. With these two wonderful persons no detail is let slide. -

Culture Report Final April 23

Appendix A to Report CS10057 Page 1 of 175 our community culture project phase 1 report - baseline cultural mapping realizing Hamilton’s potential as a creative city may 1, 2010 Appendix A to Report CS10057 Page 1 of 175 our community culture project phase 1 report - baseline cultural mapping realizing Hamilton’s potential as a creative city may 1, 2010 The photograph on the cover of this report is of the underside of the Birks Clock. The Birks Clock is part of the City of Hamilton’s Art in Public Places Collection. First located on the corner of what became the Birks Building at James South and King East, the clock was moved to the entrance of Jackson Square. The fully restored clock will hang in the Hamilton Farmers’ Market on York Blvd. Report produced by AuthentiCity for the Culture Division, Community Services Department, City of Hamilton. table of contents Photograph by Jeff Tessier Dining Room at Whitehern Historic House & Garden - Hamilton Civic Museums table of contents 5 table of contents Letter of Introduction 7 Executive Summary 10 1 Cultural Planning Definitions 20 2 Cultural Mapping Findings 26 What is Cultural Mapping? 28 OCC Phase 1 - Mapping Goals and Process 30 OCC Phase 1 - Mapping Results 32 An Ongoing Cultural Mapping System for Hamilton 36 Next Steps in Cultural Mapping 38 3 Understanding the Planning Context 40 The Creative Economy 42 Culture and Planning for Sustainability 46 Culture and Place Competitiveness 46 4 Integrating Culture in City Planning 48 Statistical Snapshot of Hamilton 50 Strategic Themes for Phase -

Open Government: Lessons from America

OPEN GOVERNMENT Lessons from America STEWART DRESNER May 1980 £3.00 OPEN GOVERNMENT: LESSONS FROM AMERICA CONTENTS Page Foreword Preface I Introduction 1 II The Open Government Concept and the British Government response 3 III Hew Open Government Legislation works in the United States 8 (1) Hie Freedom of Information Act 8 (2) The Privacy Act 25 (3) The Government in the Sunshine Act 31 IV What needs to be kept secret? 42 V Who uses the American Open Government Laws? 60 (1) Public Interest Groups 61 (2) The Media 69 (3) Individuals and Scholars 74 (4) Companies 76 (5) Civil Servants 80 VI Balancing Public Access to Government Information with the Protection of Individual Privacy 88 (1) The Issues 88 (2) The Protection of Personal Information by the U.S. Privacy Act 1974 91 (3) The Personal Privacy Exenption to the 101A 96 (4) The Relationship between the IOIA and the PA 98 (5) Public Access and Privacy Protection in an Administrative Programme 99 ii Page VII Ensuring Government Compliance with Public Access legislation 105 (1) Actaiinistrative Procedures 105 (2) Appeal Procedures 107 (3) Monitoring the Effectiveness of Public Access Legislation 117 VIII Ihe Costs and Benefits of Open Government 126 (1) National Security 127 (2) Constitutional Relationships 127 (3) Administrative and other Costs 132 IX Conclusion: Information, Democracy and Power 141 Bibliography i-xi FOREWORD Last year the related subjects of official secrets and freedom of information had a thorough but abortive airing. Mr. Clement Freud's Official Information Bill after a long and interesting committee stage became a victim of the general election.