INTARSIA and MARQUETRY OTHER VOLUMES of the SERIES by the Same Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polymer Clay Artist's Resource List

POLYMER CLAY ARTIST’S RESOURCE LIST ARTISTS: Accomplished & Emerging Artists & Teachers ............................................................................................................. 2 COMMUNITY: Guilds, Groups, Forums, & Member Communities ........................................................................................... 9 EVENTS: Workshops, retreats, classes & industry shows ............................................................................................................ 13 INFORMATION & LEARNING: Blogs, Tutorials, Publishers, & Schools ................................................................................. 14 ORGANIZATIONS: Organizations for Professional Craft Artists .............................................................................................. 17 SUPPLIES: Supplies for Polymer, Jewelry, & Sculpture ............................................................................................................... 18 SALES & MARKETS: Year-round Sales Avenues & Services ....................................................................................................... 23 TECHNIQUES & STANDARDS: Site Links and Document ....................................................................................................... 24 GENERAL TECHNIQUES/FREE TUTORIALS.......................................................................................................................... 24 PAID TUTORIAL SITES .............................................................................................................................................................. -

18Th Annual Eastern Conference of the Timber Framers Guild

Timber Framers Guild 18th Annual Eastern Conference November 14–17, 2002, Burlington, Vermont The Timber Framer’s Panel Company www.foardpanel.com P.O. Box 185, West Chesterfield, NH 03466 ● 603-256-8800 ● [email protected] Contents FRANK BAKER Healthy Businesses. 3 BRUCE BEEKEN Furniture from the Forest . 4 BEN BRUNGRABER AND GRIGG MULLEN Engineering Day to Day ENGINEERING TRACK . 6 BEN BRUNGRABER AND DICK SCHMIDT Codes: the Practical and the Possible ENGINEERING TRACK . 8 RUDY CHRISTIAN Understanding and Using Square Rule Layout WORKSHOP . 13 RICHARD CORMIER Chip Carving PRE-CONFERENCE WORKSHOP . 14 DAVID FISCHETTI AND ED LEVIN Historical Forms ENGINEERING TRACK . 15 ANDERS FROSTRUP Is Big Best or Beautiful? . 19 ANDERS FROSTRUP Stave Churches . 21 SIMON GNEHM The Swiss Carpenter Apprenticeship . 22 JOE HOWARD Radio Frequency Vacuum Drying of Large Timber: an Overview . 24 JOSH JACKSON Plumb Line and Bubble Scribing DEMONSTRATION . 26 LES JOZSA Wood Morphology Related to Log Quality. 28 MICHELLE KANTOR Construction Law and Contract Management: Know your Risks. 30 WITOLD KARWOWSKI Annihilated Heritage . 31 STEVE LAWRENCE, GORDON MACDONALD, AND JAIME WARD Penguins in Bondage DEMO 33 ED LEVIN AND DICK SCHMIDT Pity the Poor Rafter Pair ENGINEERING TRACK . 35 MATTHYS LEVY Why Buildings Don’t Fall Down FEATURED SPEAKER . 37 JAN LEWANDOSKI Vernacular Wooden Roof Trusses: Form and Repair . 38 GORDON MACDONALD Building a Ballista for the BBC . 39 CURTIS MILTON ET AL Math Wizards OPEN ASSISTANCE . 40 HARRELSON STANLEY Efficient Tool Sharpening for Professionals DEMONSTRATION . 42 THOMAS VISSER Historic Barns: Preserving a Threatened Heritage FEATURED SPEAKER . 44 Cover illustration of the Norwell Crane by Barbara Cahill. -

Carving Newsletter February 2021 Final Version-2

FEBRUARY 2021 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Hello Carvers, I want to invite you to a special member meeting on April 21st at 7:00 PM (online). Te agenda includes officially changing the name from the Western Woodcarvers Association to the Oregon Carvers Guild, adding language to become a 501c3 charitable nonproft, revising the bylaws and electing officers. To register, click here. We want to honor the 48 year legacy of the Western Woodcarvers Association and continue using the State’s legal framework but change the name. To do this we need to make a one sentence name change to the Articles of Incorporation and fle the amendment. Tis is easy, but we will make other necessary changes while we are at it. Particularly we will add boilerplate language so we can become a 501c3 nonproft, the strongest and best type. Right now we are a generic c7 nonproft which provides no beneft to donors. It will take another six months to get IRS approval after that. Members need to approve these changes. While we are at it, we are going to ask you to approve new bylaws to refect our planned organization and add protection for directors and officers. Te language for these will be voluminous but necessary. Quite boring for most of us to wade through, but quite necessary. Finally, we will vote on officers for the next fscal year, hear about our progress and plans and answer questions. If you have a desire to serve on the board, or volunteer to help in any way, please let me know. -

Wood Flooring Installation Guidelines

WOOD FLOORING INSTALLATION GUIDELINES Revised © 2019 NATIONAL WOOD FLOORING ASSOCIATION TECHNICAL PUBLICATION WOOD FLOORING INSTALLATION GUIDELINES 1 INTRODUCTION 87 SUBSTRATES: Radiant Heat 2 HEALTH AND SAFETY 102 SUBSTRATES: Existing Flooring Personal Protective Equipment Fire and Extinguisher Safety 106 UNDERLAYMENTS: Electrical Safety Moisture Control Tool Safety 110 UNDERLAYMENTS: Industry Regulations Sound Control/Acoustical 11 INSTALLATION TOOLS 116 LAYOUT Hand Tools Working Lines Power Tools Trammel Points Pneumatic Tools Transferring Lines Blades and Bits 45° Angles Wall-Layout 19 WOOD FLOORING PRODUCT Wood Flooring Options Center-Layout Trim and Mouldings Lasers Packaging 121 INSTALLATION METHODS: Conversions and Calculations Nail-Down 27 INVOLVED PARTIES 132 INSTALLATION METHODS: 29 JOBSITE CONDITIONS Glue-Down Exterior Climate Considerations 140 INSTALLATION METHODS: Exterior Conditions of the Building Floating Building Thermal Envelope Interior Conditions 145 INSTALLATION METHODS: 33 ACCLIMATION/CONDITIONING Parquet Solid Wood Flooring 150 PROTECTION, CARE Engineered Wood Flooring AND MAINTENANCE Parquet and End-Grain Wood Flooring Educating the Customer Reclaimed Wood Flooring Protection Care 38 MOISTURE TESTING Maintenance Temperature/Relative Humidity What Not to Use Moisture Testing Wood Moisture Testing Wood Subfloors 153 REPAIRS/REPLACEMENT/ Moisture Testing Concrete Subfloors REMOVAL Repair 45 BASEMENTS/CRAWLSPACES Replacement Floating Floor Board Replacement 48 SUBSTRATES: Wood Subfloors Lace-Out/Lace-In Addressing -

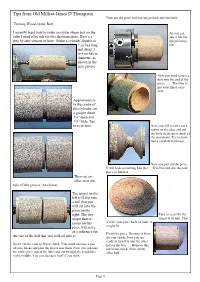

Turning Tips

Tips from Old Millrat-James D Thompson Now put the piece with the spigot back into the lathe. Turning Wood oyster Box; I recently leant how to make an oyster shape box on the As you can lathe I used silky oak for this demonstration. Here’s a see, it has the step by step version of how; Make a cylinder about 6 or spigot facing 7 inches long out. and about 3 to 4 inches in diameter. as shown in the next picture Next you need to turn a dish into the end of the piece. The time to put your finish on is now. Approximately in the centre of this cylinder cut a groove about 1/4” deep and 3/8” wide. See next picture. Next you will need to cut a radius on the edge and cut the back of the piece most of the way down. Try to main- tain a constant thickness. Now you part off the piece. It will look something like this. It will be put into the next piece to finish it. Then cut an- other near one side of this groove. As shown. The spigot on the left will slip into a bell that you will cut into the piece on the right. The tiny Turn a recess for the spigot that re- spigot to fit into. This mains on this will be your jam chuck so make it piece will serve a tight fit. as a reference for Finish the piece. Remove it from the size of the bell that you will cut into it. -

XVI, XVII XVIII Century Italian French 59° English Furniture Including Needlepoint and Tapestry Covered Examples Petit Point Ne

XV I X V I I X V I C E N T U RY T A L A N , I I I I FR E N C H 59° E N G L I S H FU R N I T U R E INCL UD ING NEED L EPO INT AND TAPESTRY CO VERED EXAMPL ES ° PETIT POINT NEEDLEWOR K B ROCADES 69 VELVETS AUBUSSON AND OTHER FINE TAPE STR I ES OR I ENTAL RUG S Fin e P orce la in Service s we Sterling Silver Tao/e Wa re ’ ’ Clz in es e Carved f7aaes a na Otlzer D eco rative A ccess ories FROM VA RIOUS PRIVATE COLL ECTIONS ESTATES AND OTHER SOURCES A M E R I C A N A R T A S S O C I A T I O N A N D E R S O N G A L L E R I E S I N C NEW YORK 1 93 1 ED T 2 01 4 - - C r e a t e d : 0 9 3 0 20 0 4 Re v i s i o n s : 1 4 ENCODI NG APB COUNTRY a e wYo r k ( St a t e ) ’ T r ice a ta loga e s A P R IC E D C O PY O F TH I S CA TA LOGU E MA Y B E O BTA I N E D FO R O N E DO LLA R FO R EACH S E S S I O N O F T H E SA LE AMERI CAN ART ASSO C IATION ND ERSO N GAL L ERIES I NC . -

Ornamental Floors Design and Installation

NATIONAL WOOD FLOORING ASSOCIATION TECHNICAL PUBLICATION No. B200 ORNAMENTAL FLOORS DESIGN AND INSTALLATION the basics of creating artistic wood flooring installations. Introduction: However, it is important to have the proper knowledge rnamental floors, in all their varied forms, about the tools required and how to use them before have become an increasingly popular choice attempting custom work. (See “Tools Required,” page 5.) Ofor many consumers who want to customize Also, while this publication will help the inexperienced their homes. The description “ornamental floors” cov- installer learn some basic concepts about custom work, ers a wide variety of options, some more difficult to the best way to become proficient is by hands-on appli- execute than others. These include feature strips, pat- cation of the techniques discussed. terned floors, hand-cut scroll work, laser-cut preman- Those wishing to become more proficient at installing ufactured inlays and borders, and mixed-media ornamental floors might do so by working with an expe- installations (involving metal, stone or tile with wood). rienced custom installer, or by attending specialized An ornamental floor may be as simple as a single, seminars designed to teach custom techniques. The 3 ⁄4-inch feature strip following the room’s perimeter. Or National Wood Flooring Association conducts such sem- it may be ornate and elaborate, involving thousands of inars periodically. Several NWFA members who have pieces that combine for a true work of art. The tech- shared their skills at NWFA installation-training semi- niques used to create these flooring effects are as var- nars and who have been honored with Floor of the Year ied as the contractors who practice them. -

The “Unknown” Maker of Marquetry Is Attributable As Buchschmid & Gretaux. I Hope You Will Publish This for Your Readers

The “Unknown” Maker Of Marquetry Is Attributable As Buchschmid & Gretaux. I hope you will publish this for your readers because it answers a question regarding an “unknown” maker of pieces owned by your previous readers. Like all antiques, these objects were made in the context of their times, and that context stays lost until somebody interested in it digs it up later. My wife and I purchased a piece of marquetry in 2018 from an online auction, local to Northern Virginia, in a lot with other home décor, described as “Germany scene wood inlay picture” shown in the attached pictures. Fig 1: Front of “Hildesheim Knochenhauer-Amtshaus”, 9 x 12 inches framed. 1 Fig 2: Rear view of original frame; note two labels, paper taping, horizontally grained wooden back, and two-pin triangular hanger. 2 Fig 3: Close-up of labels. My parents emigrated from Germany to the U.S. in the 1950s and eventually brought back lots of ‘German stuff’ passed through our family, that I grew up with. So what follows is based on not just objective facts, but also on the context of those facts that I experienced through immersion in a culture that my parents brought with them to the U.S. As with every piece, the question is always “who made it, and when?” Here, by answering the “when” first, the “who” becomes apparent. I. “WHEN” it was made Every detail is an important clue, but I draw your attention first to the labels on the back of each of the five (5) pieces, noting the following: 1) the misspellings of “INLAYD” and “COLRED” – this identical wording appears on two pieces found on your own website. -

Design Guide

® DECKING & RAILING DESIGN GUIDE 1 WHAT ARE WE MADE OF? Live Your Best Life—Outdoors The Material Difference Your outdoor living space should be a reflection of your personal You know what’s best for your outdoor living space and your lifestyle. That’s why we offer three unique material types. While we could go into detail, we’ll let the charts below and on the next style. Traditional, square decks are just the jumping off point of how page do that for us. Simply choose what’s right for you. you can use TimberTech decking to elevate your outdoor living space. But where to start? That’s where TimberTech comes in; design and technology is at the core of everything we do. CAPPED POLYMER 4-SIDED CAPPED 3-SIDED CAPPED DECKING COMPOSITE DECKING COMPOSITE DECKING UNRIVALED DESIGN AND PREMIUM STYLE AND ATTAINABLE AND ATTRACTIVE PERFORMANCE PERFORMANCE Our products, backed by premium warranties, make your deck design better, stronger, smarter, and more beautiful. Browse this guide to start bringing your design vision to life. With a wide • The most advanced synthetic • Premium composite decking • Traditional composite decking material technology without the with the added protection of a with a synthetic cap on three variety of colors, wood grains, and widths to create unique designs, use of wood particles. fully synthetic cap on all four sides and monochromatic or • Impervious to moisture. sides. color-blended options. you’ll soon be enjoying your beautifully-updated deck. • 50-Year Limited Fade & Stain • Resistant to moisture • Surface protection from ® Warranty. with Mold Guard Technology. -

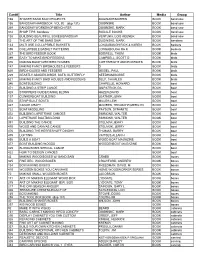

Library-By-Media.Pdf

Card# Title Author Media Group 168 SHAKER BAND SAW PROJECTS DUGINAKE/MORRIS BOOK band saw 156 BANDSAW HANDBOOK VOL #2 (dup 131) DUGINSKE BOOK band saw 369 BANDSAW WORKSHOP BENCH REF. DUGINSKE, MARK BOOK band saw 314 SHOP TIPS bandsaw RODALE BOOKS BOOK band saw 138 BUILDING BEAUTIFUL BOXES/BANDSAW VENTURA, LOIS KEENER BOOK band saw 52 THE ART OF THE BAND SAW DUGINSKE, MARK BOOK bandsaw 133 MILTI USE COLLAPSIBLE BASKETS LONGABAUGH RICK & KAREN BOOK baskets 155 COLLAPSIBLE BASKET PATTERNS LONGABOUGH R& K BOOK baskets 227 THE BIRD FEEDER BOOK BOSWELL, THOM BOOK birds 389 EASY TO MAKE BIRD FEEDERS CAMPBELL, SCOTT D BOOK birds 416 MAKING BACKYARD BIRD HOUSES CORTWRIGHT AND POKRIOTS BOOK birds 147 MAKING FANCY BIRDHOUSES & FEEDERS D BOOK birds 620 BIRD HOUSES AND FEEDERS MEISEL, PAUL BOOK birds 229 BEASTLY ABODES-BIRDS, BATS, BUTTERFLY NEEDHAM,BOBBE BOOK birds 621 MAKING FANCY BIRD HOUSES AND FEEDERS SELF, CHARLES BOOK birds 346 BOATBUILDING CHAPELLE, HOWARD BOOK boat 471 BUILDING A STRIP CANOE GILPATRICK,GIL BOOK boat 428 STRIPPERS GUIDE/CANOE BLDNG HAZEN,DAVID BOOK boat 197 CLINKERBOAT BUILDING LEATHER,JOHN BOOK boat 478 STRIP-BUILT BOATS MILLER,LEW BOOK boat 427 CANOE CRAFT MOORES, TED-MOHR,MERILYN BOOK boat 722 BOAT MODELING PAYSON, DYNAMITE BOOK boat 472 BUILDING LAPSTRAKE CANOES SIMMONS, WALTER BOOK boat 474 LAPSTRAKE BOATBUILDING SIMMONS, WALTER BOOK boat 391 BUILDING THE CANOE STELMAK,JERRY BOOK boat 470 WOOD AND CANVAS CANOE STELMOK, JERRY BOOK boat 476 BUILDING THE HERRESHOFF DINGHY THOMAS, BARRY BOOK boat 475 LOFTING VAITSES,ALLAN H BOOK boat 450 BUILD A BOAT WOOD BOAT MAGAZINE BOOK boat 477 BOAT BUILDING WOODS WOODENBOAT MAGAZINE BOOK boat 429 BLDNG BOB'S SPECIAL CANOE BOOK boat 422 HOW TO DESIGN CANOES BOOK boat 43 MAKING WOOD BOXES W/ BAND SAW CRABB BOOK boxes 325 FINE DEC. -

Past and Present

2nd Scandinavian Symposium on Furniture Technology & Design Marquetry Past and Present May 2007 Vadstena Sweden Cover photo: Detail of ‘Scarab table’ by Rasmus Malbert. Photo taken by © Rasmus Malbert. This publication was made possible thanks to Carl Malmstens Hantverksstiftelse Editor Ulf Brunne Director of Studies Carl Malmsten Furniture Studies Linköping University Tel. +46 (0) 13 28 23 20 e-mail: [email protected] Layout Elise Andersson Furniture Conservator Tel. +31 (0) 686 15 27 06 / +46 (0) 704 68 04 97 e-mail: [email protected] Foreword The Marquetry Symposium in Vadstena 2007 was all over the world. The presentations covered a the second international symposium hosted by Carl multitude of aspects and were well inline with our Malmsten Centre of Wood Technology & Design ambition to include both historical, theoretical, at Linköping University. Since then we not only technical and design related aspects. changed our name, we also moved to new purpose- Even if the symposium, as intended, covered both built premises and above all, updated our programs historical and modern applications we conclude in order to meet future challenges. Carl Malmsten that presentations of contemporary works and Furniture Studies, which is our new name, is techniques were in minority. It is therefore with great satisfaction we during the past few years have Marquetry has since ancient times been used to registered a growing interest not only in traditional decoratedefinitely furniture back on track! and interiors. Starting with basic marquetry but also in the use of marquetry on but intricate geometric patterns in the Middle Ages, industrially manufactured design furniture. -

The Ward Family of Deltaville Combined 28,220 Hours of Service to the Museum Over the Course of the Last St

Fall 2012 Mission Statement contents The mission of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is to inspire an understanding of and appreciation for the rich maritime Volunteers recognized for service heritage of the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal reaches, together with the artifacts, cultures and connections between this place and its people. Vision Statement The vision of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum is to be the premier maritime museum for studying, exhibiting, preserving and celebrating the important history and culture of the largest estuary in the United States, the Chesapeake Bay. Sign up for our e-Newsletter and stay up-to-date on all of the news and events at the Museum. Email [email protected] to be added to our mailing list. Keep up-to-date on Facebook. facebook.com/mymaritimemuseum Follow the Museum’s progress on historic Chesapeake boat 15 9 PHOTO BY DICK COOPER 2023 2313 restoration projects and updates on the (Pictured front row, from left) George MacMillan, Don Goodliffe, Pam White, Connie Robinson, Apprentice For a Day Program. Mary Sue Traynelis, Carol Michelson, Audrey Brown, Molly Anderson, Pat Scott, Paul Ray, Paul Chesapeakeboats.blogspot.com Carroll, Mike Corliss, Ron Lesher, Cliff Stretmater, Jane Hopkinson, Sal Simoncini, Elizabeth A general education forum Simoncini, Annabel Lesher, Irene Cancio, Jim Blakely, Edna Blakely. and valuable resource of stories, links, and information for the curious of minds. FEATURES (Second row, from left) David Robinson, Ann Sweeney, Barbara Reisert, Roger Galvin, John Stumpf, 3 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE 12 LIFELINES 15 Bob Petizon, Angus MacInnes, Nick Green, Bill Price, Ed Thieler, Hugh Whitaker, Jerry Friedman.